Astronomy:International Space Station programme

| |

| Organisation | |

|---|---|

| Manager |

|

| Status | Active |

| Programme history | |

| Cost | $150 billion (2010) |

| Duration | 1993–present[2] |

| First flight | Zarya November 20, 1998 |

| First crewed flight | STS-88 December 4, 1998 |

| Launch site(s) |

|

| Vehicle information | |

| Uncrewed vehicle(s) | |

| Crewed vehicle(s) |

|

| Crew capacity |

|

| Launch vehicle(s) | |

| Part of Space program of the United States |

| Space policy of the United States |

|---|

The International Space Station programme is tied together by a complex set of legal, political and financial agreements between the fifteen nations involved in the project, governing ownership of the various components, rights to crewing and utilisation, and responsibilities for crew rotation and resupply of the International Space Station. It was conceived in September 1993 by the United States and Russia after 1980s plans for separate American (Freedom) and Soviet (Mir-2) space stations failed due to budgetary reasons.[2] These agreements tie together the five space agencies and their respective International Space Station programmes and govern how they interact with each other on a daily basis to maintain station operations, from traffic control of spacecraft to and from the station, to utilisation of space and crew time. In March 2010, the International Space Station Program Managers from each of the five partner agencies were presented with Aviation Week's Laureate Award in the Space category,[3] and the ISS programme was awarded the 2009 Collier Trophy.

History and conception

As the space race drew to a close in the early 1970s, the US and USSR began to contemplate a variety of potential collaborations in outer space. This culminated in the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the first docking of spacecraft from two different spacefaring nations. The ASTP was a great success, and further joint missions were also contemplated.

One such concept was International Skylab, which proposed launching the backup Skylab B space station for a mission that would see multiple visits by both Apollo and Soyuz crew vehicles.[4] More ambitious was the Skylab-Salyut Space Laboratory, which proposed docking the Skylab B to a Soviet Salyut space station. Falling budgets and rising cold war tensions in the late 1970s saw these concepts fall by the wayside, along with another plan to have the Space Shuttle dock with a Salyut space station.[5]

In the early 1980s, NASA planned to launch a modular space station called Freedom as a counterpart to the Salyut and Mir space stations. In 1984 the ESA was invited to participate in Space Station Freedom, and the ESA approved the Columbus laboratory by 1987.[6] The Japanese Experiment Module (JEM), or Kibō, was announced in 1985, as part of the Freedom space station in response to a NASA request in 1982.

In early 1985, science ministers from the European Space Agency (ESA) countries approved the Columbus programme, the most ambitious effort in space undertaken by that organization at the time. The plan spearheaded by Germany and Italy included a module which would be attached to Freedom, and with the capability to evolve into a full-fledged European orbital outpost before the end of the century.[7]

Increasing costs threw these plans into doubt in the early 1990s. Congress was unwilling to provide enough money to build and operate Freedom, and demanded NASA increase international participation to defray the rising costs or they would cancel the entire project outright.[8]

Simultaneously, the USSR was conducting planning for the Mir-2 space station, and had begun constructing modules for the new station by the mid 1980s. However the collapse of the Soviet Union required these plans to be greatly downscaled, and soon Mir-2 was in danger of never being launched at all.[9] With both space station projects in jeopardy, American and Russian officials met and proposed they be combined. [10]

In September 1993, American Vice-President Al Gore and Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin announced plans for a new space station, which eventually became the International Space Station.[11] They also agreed, in preparation for this new project, that the United States would be involved in the Mir programme, including American Shuttles docking, in the Shuttle–Mir programme.[12]

On 12 April 2021, at a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, then-Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov announced he had decided that Russia might withdraw from the ISS programme in 2025.[13][14] According to Russian authorities, the timeframe of the station's operations has expired and its condition leaves much to be desired.[13] On 26 July 2022, Borisov, who had become head of Roscosmos, submitted to Putin his plans for withdrawal from the programme after 2024.[15] However, Robyn Gatens, the NASA official in charge of space station operations, responded that NASA had not received any formal notices from Roscosmos concerning withdrawal plans.[16] On 21 September 2022, Borisov stated that Russia was "highly likely" to continue to participate in the ISS programme until 2028.[17]

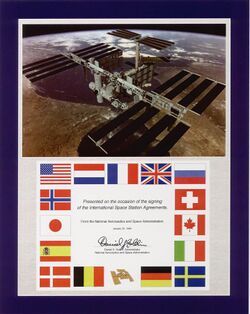

1998 agreement

The legal structure that regulates the station is multi-layered. The primary layer establishing obligations and rights between the ISS partners is the Space Station Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA), an international treaty signed on January 28, 1998 by fifteen governments involved in the space station project. The ISS consists of Canada, Japan, the Russian Federation, the United States, and eleven Member States of the European Space Agency (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom).[18] Article 1 outlines its purpose:

This Agreement is a long term international co-operative framework on the basis of genuine partnership, for the detailed design, development, operation, and utilization of a permanently inhabited civil Space Station for peaceful purposes, in accordance with international law.[19]

The IGA sets the stage for a second layer of agreements between the partners referred to as 'Memoranda of Understanding' (MOUs), of which four exist between NASA and each of the four other partners. There are no MOUs between ESA, Roskosmos, CSA and JAXA because NASA is the designated manager of the ISS. The MOUs are used to describe the roles and responsibilities of the partners in more detail.

A third layer consists of bartered contractual agreements or the trading of the partners' rights and duties, including the 2005 commercial framework agreement between NASA and Roscosmos that sets forth the terms and conditions under which NASA purchases seats on Soyuz crew transporters and cargo capacity on uncrewed Progress transporters.

A fourth legal layer of agreements implements and supplements the four MOUs further. Notably among them is the ISS code of conduct made in 2000, setting out criminal jurisdiction, anti-harassment and certain other behavior rules for ISS crewmembers.[20]

Programme operations

Expeditions

Private flights

Fleet operations

Crewed

As of March 2023, the United Arab Emirates has sent its second astronaut.

Uncrewed

Repairs

Mission control centres

The components of the ISS are operated and monitored by their respective space agencies at mission control centres across the globe, including:

- Roscosmos' RKA Mission Control Center at Korolyov, Russia — manages the maintaining of the station, controls launches of the crewed missions, guides launches from Baikonur Cosmodrome

- ESA's ATV Control Centre, at the Toulouse Space Centre (CST) in Toulouse, France – controlled flights of the uncrewed European Automated Transfer Vehicle[21]

- JAXA's JEM Control Center and HTV Control Center at Tsukuba Space Center (TKSC) in Ibaraki, Japan – responsible for operating the Kibō complex and all flights of the White Stork HTV Cargo spacecraft, respectively[21]

- NASA's Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Mission Control Center at Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas – serves as the primary control facility for the United States segment of the ISS[21]

- NASA's Payload Operations and Integration Center at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama – coordinates payload operations in the USOS[21]

- ESA's Columbus Control Center at the German Aerospace Center in Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany – manages the European Columbus research laboratory[21]

- CSA's MSS Control at Saint-Hubert, Quebec, Canada – controls and monitors the Mobile Servicing System[21]

Politics

Usage of crew and hardware

Future of the ISS

Former NASA Administrator Michael D. Griffin says the International Space Station has a role to play as NASA moves forward with a new focus for the crewed space programme, which is to go out beyond Earth orbit for purposes of human exploration and scientific discovery. "The International Space Station is now a stepping stone on the way, rather than being the end of the line", Griffin said.[22] Griffin has said that station crews will not only continue to learn how to live and work in space, but also will learn how to build hardware that can survive and function for the years required to make the round-trip voyage from Earth to Mars.[22]

Despite this view, however, in an internal e-mail leaked to the press on August 18, 2008 from Griffin to NASA managers,[23][24][25] Griffin apparently communicated his belief that the current US administration had made no viable plan for US crews to participate in the ISS beyond 2011, and that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) were actually seeking its demise.[24] The e-mail appeared to suggest that Griffin believed the only reasonable solution was to extend the operation of the Space Shuttle beyond 2010, but noted that Executive Policy (i.e. the White House) was firm that there would be no extension of the Space Shuttle retirement date, and thus no US capability to launch crews into orbit until the Orion spacecraft would become operational in 2020 as part of the Constellation programme. He did not see purchase of Russian launches for NASA crews as politically viable following the 2008 South Ossetia war, and hoped the incoming Barack Obama administration would resolve the issue in 2009 by extending Space Shuttle operations beyond 2010.

A solicitation issued by NASA JSC indicates NASA's intent to purchase from Roscosmos "a minimum of 3 Soyuz seats up to a maximum of 24 seats beginning in the Spring of 2012" to provide ISS crew transportation.[26][27]

On September 7, 2008, NASA released a statement regarding the leaked email, in which Griffin said:

The leaked internal email fails to provide the contextual framework for my remarks, and my support for the administration's policies. Administration policy is to retire the shuttle in 2010 and purchase crew transport from Russia until Ares and Orion are available. The administration continues to support our request for an INKSNA exemption. Administration policy continues to be that we will take no action to preclude continued operation of the International Space Station past 2016. I strongly support these administration policies, as do OSTP and OMB.—Michael D. Griffin[28]

On October 15, 2008, President Bush signed the NASA Authorization Act of 2008, giving NASA funding for one additional mission to "deliver science experiments to the station".[29][30][31][32] The Act allows for an additional Space Shuttle flight, STS-134, to the ISS to install the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, which was previously cancelled.[33]

President of the United States Barack Obama has supported the continued operation of the station, and supported the NASA Authorization Act of 2008.[33] Obama's plan for space exploration includes finishing the station and completion of the US programmes related to the Orion spacecraft.[34]

End of mission

New partners

China has reportedly expressed interest in the project, especially if it would be able to work with the RKA. Due to national security concerns, the United States Congress passed a law prohibiting contact between US and Chinese space programmes.[35] (As of 2019), China is not involved in the International Space Station.[36] In addition to national security concerns, United States objections include China's human rights record and issues surrounding technology transfer.[37][38] The heads of both the South Korean and Indian space agencies announced at the first plenary session of the 2009 International Astronautical Congress on 12 October that their nations intend to join the ISS programme. The talks began in 2010, and were not successful. The heads of agency also expressed support for extending ISS lifetime.[39] European countries not a part of the International Space Station programme will be allowed access to the station in a three-year trial period, ESA officials say.[40] The Indian Space Research Organisation has made it clear that it will not join the ISS and will instead build its own space station.[41]

Cost

Public opinion

The International Space Station has been the target of varied criticism over the years. Critics contend that the time and money spent on the ISS could be better spent on other projects—whether they be robotic spacecraft missions, space exploration, investigations of problems here on Earth, or just tax savings.[42] Some critics, like Robert L. Park, argue that very little scientific research was convincingly planned for the ISS in the first place.[43] They also argue that the primary feature of a space-based laboratory is its microgravity environment, which can usually be studied more cheaply with a "vomit comet".[44]

One of the most ambitious ISS modules to date, the Centrifuge Accommodations Module, has been cancelled due to the prohibitive costs NASA faces in simply completing the ISS. As a result, the research done on the ISS is generally limited to experiments which do not require any specialized apparatus. For example, in the first half of 2007, ISS research dealt primarily with human biological responses to being in space, covering topics like kidney stones, circadian rhythm, and the effects of cosmic rays on the nervous system.[45][46][47]

Other critics have attacked the ISS on some technical design grounds:

- Jeff Foust argued that the ISS requires too much maintenance, especially by risky, expensive EVAs.[48] The magazine The American Enterprise reports, for instance, that ISS astronauts "now spend 85 percent of their time on construction and maintenance" alone.[citation needed]

- The Astronomical Society of the Pacific has mentioned that its orbit is rather highly inclined, which makes Russian launches cheaper, but US launches more expensive.[49]

Critics[who?] also say that NASA is often casually credited with "spin-offs" (such as Velcro and portable computers) that were developed independently for other reasons.[50] NASA maintains a list of spin-offs from the construction of the ISS, as well as from work performed on the ISS.[51][52]

In response to some of these criticisms, advocates of human space exploration say that criticism of the ISS programme is short-sighted, and that crewed space research and exploration have produced billions of dollars' worth of tangible benefits to people on Earth. Jerome Schnee estimated that the indirect economic return from spin-offs of human space exploration has been many times the initial public investment.[53] A review of the claims by the Federation of American Scientists argued that NASA's rate of return from spin-offs is actually "astoundingly bad", except for aeronautics work that has led to aircraft sales.[54]

It is therefore debatable whether the ISS, as distinct from the wider space programme, is a major contributor to society. Some advocates[who?] argue that apart from its scientific value, it is an important example of international cooperation.[55] Others[who?] claim that the ISS is an asset that, if properly leveraged, could allow more economical crewed Lunar and Mars missions.[56]

Notes

References

- ↑ Harbaugh, Jennifer (2015-08-19). "August 19, 2015". http://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/about/star/star150819.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Holmes, Steven A (1993-09-03). "US And Russians Join in new plan for Space Station". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/09/03/world/us-and-russians-join-in-new-plan-for-space-station.html. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ↑ "India space station India plans to launch space station by 2030 Space Station". 18 Oct 2019. https://techandresults.com/india-space-station-india-plans-to-launch-space-station-by-2030-space-station/.

- ↑ Frieling, Thomas. "Skylab B:Unflown Missions, Lost Opportunities". QUEST 5 (4): 12–21. http://forum.nasaspaceflight.com/index.php?action=dlattach;topic=13040.0;attach=106506.

- ↑ Portree, David S. F.. "Skylab-Salyut Space Laboratory (1972)". Wired. https://www.wired.com/2012/03/skylab-salyut-space-laboratory-1972/.

- ↑ ESA - Columbus

- ↑ "International Space Station". Astronautix.com. http://www.astronautix.com/craft/intation.htm.

- ↑ "fate of space station is in doubt as all options exceed cost goals". The New York Times. 8 June 1993. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/08/science/fate-of-space-station-is-in-doubt-as-all-options-exceed-cost-goals.html.

- ↑ "Mir-2". Astronautix. http://www.astronautix.com/m/mir-2.html.

- ↑ "U.S. PROPOSES SPACE MERGER WITH RUSSIA". The Washington Post. 5 November 1993. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1993/11/05/us-proposes-space-merger-with-russia/88a4b85e-ade1-4f53-9cf3-df97a5be891d/.

- ↑ Heivilin, Donna (21 June 1994). "Space Station: Impact of the Expanded Russian Role on Funding and Research". Government Accountability Office. http://archive.gao.gov/t2pbat3/151975.pdf.

- ↑ Dismukes, Kim (4 April 2004). "Shuttle–Mir History/Background/How "Phase 1" Started". NASA. http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/history/shuttle-mir/history/h-b-start.htm.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Russia to decide on pullout from ISS since 2025 after technical inspection". TASS. 18 April 2021. https://tass.com/science/1279545. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ Dobrovidova, Olga (20 April 2021). "Russia mulls withdrawing from the International Space Station after 2024". Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)). doi:10.1126/science.abj1005. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ↑ Harwood, William (26 July 2022). "Russia says it will withdraw from the International Space Station after 2024". ViacomCBS. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/russia-international-space-station-exit-2024/.

- ↑ Roulette, Joey (26 July 2022). "Russia signals space station pullout, but NASA says it's not official yet". https://www.reuters.com/technology/russia-has-not-signaled-space-station-withdrawal-nasa-us-official-says-2022-07-26/.

- ↑ "Russia is likely to take part in International Space Station until 2028 -RIA". Reuters. 21 September 2022. https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/russia-is-likely-take-part-international-space-station-until-2028-ria-2022-09-21/.

- ↑ "International Space Station - International Cooperation". March 25, 2015. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/cooperation/index.html.

- ↑ "International Space Station Legal Framework". International Space Station. European Space Agency. 20 July 2001. http://www.esa.int/esaHS/ESAH7O0VMOC_iss_0.html.

- ↑ Farand, Andre. "Astronauts' behaviour onboard the International Space Station: regulatory framework". International Space Station. UNESCO. http://portal.unesco.org/shs/en/file_download.php/785db0eec4e0cdfc43e1923624154cccFarand.pdf.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Gary Kitmacher (2006). Reference Guide to the International Space Station. Canada: Apogee Books. 71–80. ISBN 978-1-894959-34-6.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Griffin, Michael (July 18, 2001). "Why Explore Space?". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/exploration/main/griffin_why_explore.html.

- ↑ Malik, Tariq (2008). "NASA Chief Vents Frustration in Leaked E-mail". Space.com (Imaginova Corp). http://www.space.com/news/080907-nasa-griffin-email.html.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Orlando Sentinel (July 7, 2008). "Internal NASA email from NASA Administrator Griffin". SpaceRef.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewsr.html?pid=29133.

- ↑ Griffin, Michael (2008). "Michael Griffin email image" (jpg). Orlando Sentinel. http://blogs.orlandosentinel.com/news_space_thewritestuff/files/GriffinEmail.jpg.

- ↑ "PROCUREMENT OF CREW TRANSPORTATION AND RESCUE SERVICES FROM ROSCOSMOS". NASA JSC. http://prod.nais.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/eps/synopsis.cgi?acqid=134686.

- ↑ "Modification". NASA JSC. http://prod.nais.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/eps/synopsis.cgi?acqid=134857.

- ↑ "Statement of NASA Administrator Michael Griffin on Aug. 18 Email" (Press release). NASA. September 7, 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ↑ "To authorize the programs of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.". Library of Congress. 2008. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d110:h.r.06063:.

- ↑ Berger, Brian (June 19, 2008). "House Approves Bill for Extra Space Shuttle Flight". Space.com (Imaginova Corp). http://www.space.com/news/080619-house-shuttle-flight-bill.html.

- ↑ NASA (September 27, 2008). "House Sends NASA Bill to President's Desk". Spaceref.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=26558.

- ↑ Matthews, Mark (October 15, 2008). "Bush signs NASA authorization act". Orlando Sentinel. http://blogs.orlandosentinel.com/news_space_thewritestuff/2008/10/bush-signs-nasa.html.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Berger, Brian for Space.com (September 23, 2008). "Obama backs NASA waiver, possible shuttle extension". USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/space/2008-09-23-obama-nasa-shuttle_N.htm.

- ↑ BarackObama.com (2008). "Barack Obama's Plan For American Leadership in Space". Spaceref.com. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewsr.html?pid=26647.

- ↑ Jeffrey, Kluger. "The Silly Reason the Chinese Aren't Allowed on the Space Station". Time. https://time.com/3901419/space-station-no-chinese/. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ↑ Mark, Garcia (March 25, 2015). "International Cooperation". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/cooperation/index.html.

- ↑ "China wants role in space station". Associated Press. CNN. 16 October 2007. http://www.cnn.com/2007/TECH/space/10/16/china.space.ap/index.html.

- ↑ James Oberg (26 October 2001). "China takes aim at the space station". NBC News. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/3077826.

- ↑ "South Korea, India to begin ISS partnership talks in 2010". Flight International. October 14, 2009. http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/2009/10/14/333406/south-korea-india-to-begin-iss-partnership-talks-in.html.

- ↑ "EU mulls opening ISS to more countries". http://www.space-travel.com/reports/EU_mulls_opening_ISS_to_more_countries_999.html.

- ↑ "India planning to have own space station: ISRO chief". The Economic Times. 2019-06-13. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/science/india-planning-to-have-own-space-station-isro-chief/articleshow/69771669.cms.

- ↑ Mail & Guardian. "A waste of space". Mail & Guardian. http://www.mg.co.za/article/2006-01-26-a-waste-of-space.

- ↑ Park, Bob. "Space Station: Maybe They Could Use It to Test Missile Defense". http://bobpark.physics.umd.edu/WN04/wn092404.html.

- ↑ Park, Bob. "Space: International Space Station Unfurls New Solar Panels". http://bobpark.physics.umd.edu/WN06/wn091506.html.

- ↑ NASA (2007). "Renal Stone Risk During Spaceflight: Assessment and Countermeasure Validation (Renal Stone)". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/science/experiments/Renal-Stone.html.

- ↑ NASA (2007). "Sleep-Wake Actigraphy and Light Exposure During Spaceflight-Long (Sleep-Long)". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/science/experiments/Sleep-Long.html.

- ↑ NASA (2007). "Anomalous Long Term Effects in Astronauts' Central Nervous System (ALTEA)". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/science/experiments/ALTEA.html.

- ↑ Jeff Foust (2005). "The trouble with space stations". The Space Review. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/453/1.

- ↑ "Up, Up, and Away". Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 1996. http://www.astrosociety.org/education/publications/tnl/34/space2.html.

- ↑ Park, Robert. "The Virtual Astronaut". The New Atlantis. http://www.thenewatlantis.com/archive/4/park.htm.

- ↑ NASA (2007). "NASA Spinoff". NASA Scientific and Technical Information (STI). http://www.sti.nasa.gov/tto/.

- ↑ NASA Center for AeroSpace Information (CASI) (2005-10-21). "International Space Station Spinoffs". NASA. http://www.sti.nasa.gov/tto/ISSspin.html.

- ↑ "Economic impact of large public programs The NASA experience". NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS). 1976. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=640676&id=1&qs=Ntt%3DSchnee%26Ntk%3Dall%26Ntx%3Dmode%2520matchall%26N%3D0%26Ns%3DPublicationYear%257C0.

- ↑ Federation of American Scientists. "NASA Technological Spinoff Fables". Federation of American Scientists. https://fas.org/spp/eprint/jp_950525.htm.

- ↑ Space Today Online (2003). "International Space Station: Human Residency Third Anniversary". Space Today Online. http://www.spacetoday.org/SpcStns/FirstAnnivOccupy.html.

- ↑ RSC Energia (2005). "Interview with Niolai (sic) Sevostianov, President, RSC Energia: The mission to Mars is to be international". Mars Today.com/SpaceRef Interactive Inc. http://www.marstoday.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=18482.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:International Space Station program. |

- ESA - Columbus

- JAXA - Space Environment Utilization and Space Experiment

- NASA - Station Science

- RSC Energia - Science Research on ISS Russian Segment

|