Dual lattice

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

In the theory of lattices, the dual lattice is a construction analogous to that of a dual vector space. In certain respects, the geometry of the dual lattice of a lattice [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] is the reciprocal of the geometry of [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math], a perspective which underlies many of its uses.

Dual lattices have many applications inside of lattice theory, theoretical computer science, cryptography and mathematics more broadly. For instance, it is used in the statement of the Poisson summation formula, transference theorems provide connections between the geometry of a lattice and that of its dual, and many lattice algorithms exploit the dual lattice.

For an article with emphasis on the physics / chemistry applications, see Reciprocal lattice. This article focuses on the mathematical notion of a dual lattice.

Definition

Let [math]\displaystyle{ L \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n }[/math] be a lattice. That is, [math]\displaystyle{ L = B \mathbb{Z}^n }[/math] for some matrix [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math].

The dual lattice is the set of linear functionals on [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] which take integer values on each point of [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ L^* = \{ f \in (\text{span}(L))^* : \forall x \in L, f(x) \in \mathbb{Z} \}. }[/math]

If [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathbb{R}^n)^* }[/math] is identified with [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^n }[/math] using the dot-product, we can write [math]\displaystyle{ L^* = \{ v \in \text{span}(L) : \forall x \in L, v \cdot x \in \mathbb{Z} \}. }[/math] It is important to restrict to vectors in the span of [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math], otherwise the resulting object is not a lattice.

Despite this identification of ambient Euclidean spaces, it should be emphasized that a lattice and its dual are fundamentally different kinds of objects; one consists of vectors in Euclidean space, and the other consists of a set of linear functionals on that space. Along these lines, one can also give a more abstract definition as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ L^* = \{ f : L \to \mathbb{Z} : \text{f is a linear function} \} = \text{Hom}_{\text{Ab}}(L, \mathbb{Z}). }[/math]

However, we note that the dual is not considered just as an abstract Abelian group of functionals, but comes with a natural inner product: [math]\displaystyle{ f \cdot g = \sum_i f(e_i) g(e_i) }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ e_i }[/math] is an orthonormal basis of [math]\displaystyle{ \text{span}(L) }[/math]. (Equivalently, one can declare that, for an orthonormal basis [math]\displaystyle{ e_i }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ \text{span}(L) }[/math], the dual vectors [math]\displaystyle{ e^*_i }[/math], defined by [math]\displaystyle{ e_i^*(e_j) = \delta_{ij} }[/math] are an orthonormal basis.) One of the key uses of duality in lattice theory is the relationship of the geometry of the primal lattice with the geometry of its dual, for which we need this inner product. In the concrete description given above, the inner product on the dual is generally implicit.

Properties

We list some elementary properties of the dual lattice:

- If [math]\displaystyle{ B = [b_1, \ldots, b_n] }[/math] is a matrix giving a basis for the lattice [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ z \in \text{span}(L) }[/math] satisfies [math]\displaystyle{ z \in L^* \iff b^T_i z \in \mathbb{Z}, i = 1, \ldots, n \iff B^T z \in \mathbb{Z}^n }[/math].

- If [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is a matrix giving a basis for the lattice [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ B (B^T B)^{-1} }[/math] gives a basis for the dual lattice. If [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] is full rank [math]\displaystyle{ B^{-T} }[/math] gives a basis for the dual lattice: [math]\displaystyle{ z \in L^* \iff B^T z \in \mathbb{Z}^n \iff z \in B^{-T} \mathbb{Z}^n }[/math].

- The previous fact shows that [math]\displaystyle{ (L^*)^* = L }[/math]. This equality holds under the usual identifications of a vector space with its double dual, or in the setting where the inner product has identified [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^n }[/math] with its dual.

- Fix two lattices [math]\displaystyle{ L,M }[/math]. Then [math]\displaystyle{ L \subseteq M }[/math] if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ L^* \supseteq M^* }[/math].

- The determinant of a lattice is the reciprocal of the determinant of its dual: [math]\displaystyle{ \text{det}(L^*) = \frac{1}{\text{det}(L)} }[/math]

- If [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] is a nonzero scalar, then [math]\displaystyle{ (qL)^* = \frac{1}{q} L^* }[/math].

- If [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] is a rotation matrix, then [math]\displaystyle{ (RL)^* = R L^* }[/math].

- A lattice [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] is said to be integral if [math]\displaystyle{ x \cdot y \in \mathbb{Z} }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ x,y \in L }[/math]. Assume that the lattice [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math]is full rank. Under the identification of Euclidean space with its dual, we have that [math]\displaystyle{ L \subseteq L^* }[/math] for integral lattices [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math]. Recall that, if [math]\displaystyle{ L' \subseteq L }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ |L/L'| \lt \infty }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ \text{det}(L') = \text{det}(L) | L/L'| }[/math]. From this it follows that for an integral lattice, [math]\displaystyle{ \text{det}(L)^2 = | L^* / L| }[/math].

- An integral lattice is said to be unimodular if [math]\displaystyle{ L = L^* }[/math], which, by the above, is equivalent to [math]\displaystyle{ \text{det}(L) = 1. }[/math]

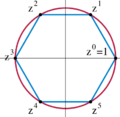

Examples

Using the properties listed above, the dual of a lattice can be efficiently calculated, by hand or computer. Certain lattices with importance in mathematics and computer science are dual to each other, and we list some here.

Elementary examples

- The dual of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}^n }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}^n }[/math].

- The dual of [math]\displaystyle{ 2\mathbb{Z} \oplus \mathbb{Z} }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{2} \mathbb{Z} \oplus \mathbb{Z} }[/math].

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ L = \{ x \in \mathbb{Z}^n : \sum x_i = 0 \mod 2 \} }[/math] be the lattice of integer vectors whose coordinates have an even sum. Then [math]\displaystyle{ L^* = \mathbb{Z}^n + (\frac{1}{2}, \ldots, \frac{1}{2}) }[/math], that is, the dual is the lattice generated by the integer vectors along with the all [math]\displaystyle{ 1/2 }[/math]s vector.

q-ary lattices

An important class of examples, particularly in lattice cryptography, are given by the q-ary lattices. For a matrix [math]\displaystyle{ A \in \mathbb{F}_q^{m \times n}, }[/math] we define [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta_q(A) = \{ x \in \mathbb{Z}^n : x \mod q \in A^T \mathbb{F}_q^m \}, \Delta_q^{\perp}(A) = \{ x \in \mathbb{Z}^n : Ax = 0 \mod q \} }[/math]; these are called, respectively, the image and kernel q-ary lattices associated to [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]. Then, after identifying Euclidean space with its dual, we have that the image and kernel q-ary lattices of a matrix [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] are dual, up to a scalar. In particular, [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta_q(A)^* = \frac{1}{q} \Delta_q^{\perp}(A) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta_q^{\perp}(A)^* = \frac{1}{q} \Delta_q(A) }[/math].[citation needed] (The proof can be done as an exercise.)

Transference theorems

Each [math]\displaystyle{ f \in L^* \setminus \{0\} }[/math] partitions [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] according to the level sets corresponding to each of the integer values. Smaller choices of [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] produce level sets with more distance between them; in particular, the distance between the layers is [math]\displaystyle{ 1 / ||f|| }[/math]. Reasoning this way, one can show that finding small vectors in [math]\displaystyle{ L^* }[/math] provides a lower bound on the largest size of non-overlapping spheres that can be placed around points of [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math]. In general, theorems relating the properties of a lattice with properties of its dual are known as transference theorems. In this section we explain some of them, along with some consequences for complexity theory.

We recall some terminology: For a lattice [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] , let [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda_i(L) }[/math] denote the smallest radius ball that contains a set of [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] linearly independent vectors of [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math]. For instance, [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda_1(L) }[/math] is the length of the shortest vector of [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mu(L) = \text{max}_{x \in \mathbb{R}^n } d(x, L) }[/math] denote the covering radius of [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math].

In this notation, the lower bound mentioned in the introduction to this section states that [math]\displaystyle{ \mu(L) \geq \frac{1}{2 \lambda_1(L^*)} }[/math].

Theorem (Banaszczyk)[1] — For a lattice [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \leq 2 \lambda_1(L) \mu(L^*) \leq n }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \leq \lambda_i(L) \lambda_{n - i + 1}(L^*) \leq n }[/math]

There always an efficiently checkable certificate for the claim that a lattice has a short nonzero vector, namely the vector itself. An important corollary of Banaszcyk's transference theorem is that [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda_1(L) \geq \frac{1}{\lambda_n(L^*)} }[/math], which implies that to prove that a lattice has no short vectors, one can show a basis for the dual lattice consisting of short vectors. Using these ideas one can show that approximating the shortest vector of a lattice to within a factor of n (the [math]\displaystyle{ \text{GAPSVP} n }[/math] problem) is in [math]\displaystyle{ \text{NP} \cap \text{coNP} }[/math].[citation needed]

Other transference theorems:

- The relationship [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda_1(L) \lambda_1(L^*) \leq n }[/math] follows from Minkowski's bound on the shortest vector; that is, [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda_1(L) \leq \sqrt{n} (\text{det}(L)^{1/n}) }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda_1(L^*) \leq \sqrt{n} (\text{det}(L^*)^{1/n}) }[/math], from which the claim follows since [math]\displaystyle{ \text{det}(L) = \frac{1}{\text{det}(L^*)} }[/math].

Poisson summation formula

The dual lattice is used in the statement of a general Poisson summation formula.

Theorem — Theorem (Poisson Summation)[2] Let [math]\displaystyle{ f : \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R} }[/math] be a well-behaved function, such as a Schwartz function, and let [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{f} }[/math] denote its Fourier transform. Let [math]\displaystyle{ L \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n }[/math] be a full rank lattice. Then:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{x \in L} f(x) = \frac{1}{\det(L)} \sum_{y \in L^*} \hat{f}(y) }[/math].

Further reading

- Ebeling, Wolfgang (2013). "Lattices and Codes". Advanced Lectures in Mathematics. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-00360-9. ISBN 978-3-658-00359-3.

References

- ↑ Banaszczyk, W. (1993). "New bounds in some transference theorems in the geometry of numbers". Mathematische Annalen (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 296 (1): 625–635. doi:10.1007/bf01445125. ISSN 0025-5831.

- ↑ Cohn, Henry; Kumar, Abhinav; Reiher, Christian; Schürmann, Achill (2014). "Formal duality and generalizations of the Poisson summation formula". Discrete Geometry and Algebraic Combinatorics. Contemporary Mathematics. 625. pp. 123–140. doi:10.1090/conm/625/12495. ISBN 9781470409050.

|