Astronomy:Mars Cube One

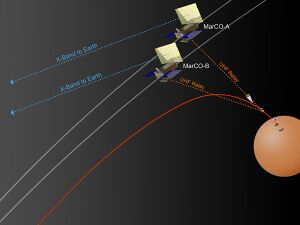

Rendering of the two MarCO spacecraft in communications relay | |

| Mission type | Communications relay test Mars flyby |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| Website | www |

| Mission duration | MARCO A: 7 months and 30 days MARCO B: 7 months and 24 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft type | 6U CubeSat |

| Manufacturer | JPL |

| Launch mass | 13.5 kg (30 lb) each[1] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 5 May 2018, 11:05 UTC[2] |

| Rocket | Atlas V 401 |

| Launch site | Vandenberg Air Force Base SLC-3E |

| Contractor | United Launch Alliance |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Abandoned In Solar Orbit |

| Declared | 2 February 2020 |

| Last contact | MarCO-A: 4 January 2019[3]

MarCO-B: 29 December 2018[3] |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | heliocentric |

| Flyby of Mars | |

| Closest approach | 26 November 2018, 19:52:59 UTC |

| Distance | 3,500 km (2,200 mi)[4] |

Discovery program | |

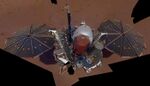

Mars Cube One (or MarCO) was a Mars flyby mission launched on 5 May 2018 alongside NASA's InSight Mars lander.[5] It consisted of two nanospacecraft, MarCO-A and MarCO-B, that provided real-time communications to Earth for InSight during its entry, descent, and landing (EDL) on 26 November 2018 - when InSight was out of line of sight from the Earth.[6] Both spacecraft were 6U CubeSats designed to test miniaturized communications and navigation technologies. These were the first CubeSats to operate beyond Earth orbit, and aside from telecommunications they also tested CubeSats' endurance in deep space. On 5 February 2019, NASA reported that both the CubeSats had gone silent by 5 January 2019, and are unlikely to be heard from again.[3] In August 2019, the CubeSats were honored for their role in the successful landing of the InSight lander on Mars.[7]

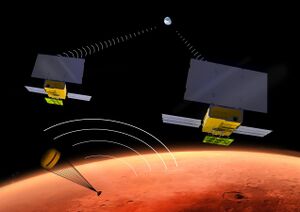

The InSight lander re-transmitted its telemetry data during the landing, which demonstrated the new relay system and technology for future use in missions to other Solar System bodies. This provided an alternative to the orbiters for relaying information and achieved a technology development threshold.

After the MarCO satellites went silent in January 2019, there was a chance that communications with the satellites could be reestablished in the second half of 2019 as the satellites moved into more favorable location in space. NASA launched a campaign to establish communication with the satellites in September 2019. The communication attempts were unsuccessful and on 2 February 2020 NASA announced Mars Cube One mission formally ended.[8]

Overview

Mars Cube One is the first spacecraft built to the CubeSat form to operate beyond Earth orbit for a deep space mission. CubeSats are made of small components that are desirable for multiple reasons, including low cost of construction,[9] quick development, simple systems, and ease of deployment to low Earth orbit. They have been used for many research purposes, including: biological endeavors, mapping missions, etc. CubeSat technology was developed by California Polytechnic State University and Stanford University, with the purpose of quick and easy projects that would allow students to make use of the technology. They are often packaged as part of the payload for a larger mission, making them even more cost effective.[10]

The two Mars Cube One spacecraft are identical and officially called MarCO-A and MarCO-B and were launched together for redundancy; they were nicknamed by JPL engineers as WALL-E and EVE in reference to the main characters in the animated film WALL-E.[11][12] The MarCO mission cost was US$18.5 million.[13]

JPL's MarCO engineers view the Mars flyby as a technology demonstration that could lead to many more low-cost, targeted small satellite missions outside of Earth's orbit.[14] While keeping an eye on the performance of the MarCO mission, NASA has proposed spending more money on CubeSats as a complement to multi-billion-dollar projects which sometimes face years of delay.[15]

Launch and cruise

The launch of Mars Cube One was managed by NASA's Launch Services Program. The launch was scheduled for 4 March 2016 on an Atlas V 401,[16] but the mission was postponed to 5 May 2018 after a major test failure of an InSight scientific instrument.[17] The Atlas V rocket launched the spacecraft together with InSight, then the two MarCO separated soon after launch to fly their own trajectory to Mars[18] in order to test CubeSats' endurance and navigation in deep space.[19][20]

During the cruise phase, the two spacecraft were kept about 10,000 km (6,200 mi) away from InSight at either flank for safety, and the distance was reduced as the three spacecraft approached Mars.[13] The closest flyby distance to Mars was 3,500 km (2,200 mi).[4]

Objectives

The primary mission of MarCO is to test new miniaturized communication and navigation technologies. They were able to provide real-time communication relay while the InSight lander was in the entry, descent, landing (EDL) phase.[22]

The MarCO spacecraft were launched as a pair (named WALL-E and EVE for the movie characters) for redundancy, and flew at either side of InSight. While there are a large number of CubeSats around Earth, Mars Cube One is the first CubeSat mission to go beyond Earth orbit. This allowed for collection of unique data outside of the Earth's atmosphere and orbit. In addition to serving as communications relays, they also tested the CubeSat components' endurance and navigation capabilities in deep space. Instead of waiting several hours for the information to relay back to Earth directly from the InSight lander, MarCO thus relayed EDL-critical data immediately, (subject only to the 8 minute Mars-Earth transmission time) after the completion of the landing.[23][22][24] The information sent to Earth included an image from InSight of the Martian surface right after the lander touched down.[25][26]

Without the MarCO CubeSats, InSight would relay the flight information to the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) which does not transmit information as quickly. Seeing the already-present difficulty in communicating with ground control during especially risky situations, various teams set out to revise the way in which data is relayed back to Earth. Previous missions would send data directly to Earth after landing, or to nearby orbiters, which would then relay the information.[22] Future missions may no longer choose to rely on these methods, since CubeSats may be able to improve data relay in real time, as well as reduce the overall mission cost.[18]

Design and components

The design includes two communication-relay CubeSats, built by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which are of the 6U specification (10×20×30 cm). A limiting factor to the development of CubeSats is that all necessary components must fit within the frame of the satellite. It must contain the antenna, avionics to control the satellite, a propulsion system, power, and payload.[22]

Data relay

On board the two CubeSats is an ultra-high frequency (UHF) antenna with circular polarization. EDL information from InSight was transmitted through the UHF band at 8 kbit/s to the CubeSats, and was simultaneously retransmitted at an X band frequency at 8 kbit/s to Earth.[22] MarCO used a deployable solar panel for power, but because of the limitations in solar panel efficiency, the power for the X-band frequency can only be about 5 watts.

For the CubeSats to relay information, they need a high gain antenna (HGA) which is reliable, meets the mass specs, has low complexity, and is affordable to build. A high gain antenna (directional antenna) is one that has a focused, narrow radiowave beamwidth. Three possible types were assessed: a standard microstrip patch antenna, a reflectarray, and a mesh reflector. With the small, flat, size required for the CubeSats, the reflectarray antenna type met all of the mission needs. The components of the reflectarray HGA are three folded panels, a root hinge which connects the wings to the body of the CubeSat, four wing hinges, and a burn wire release mechanism. The antenna panels must be able to withstand temperature changes throughout the mission as well as vibrations during deployment.[22] MarCO relayed EDL-critical data immediately upon landing.[23][25] These signals arrived on Earth eight minutes later.

Propulsion

The propulsion system features eight cold gas thrusters which control the trajectory, and a reaction control system to adjust their attitude (3D orientation).[27] On the way to the correct transmission destination, the propulsion system made five small corrections to ensure the two small spacecraft were on the correct trajectory.[28] Small changes in trajectory early on in the mission's deployment not only saved fuel but also the space which any extra fuel would have taken up, thus conserving volume for other important components inside the spacecraft. MarCO-B (WALL-E) had been leaking propellant gas almost since liftoff, but early assessments indicated it had enough to complete its mission.[13]

Having completed their primary mission, the small spacecraft shall continue in their elliptical orbits around the Sun. Engineers expect them to keep working for a couple weeks after they pass Mars orbit, depending on how long their propellant and electronics last.[13]

Each MarCO carries a softball-sized radio used to communicate with the ground using X-band, to receive data from InSight using UHF, and to collect tracking measurements for navigation. Their attitude control system is equipped with a star tracker that is used to determine the attitude of the spacecraft.[1][29] In addition, each MarCO carries a miniature wide-angle camera that is used to verify deployments and to capture outreach images.[30][1]

Similar missions beyond Earth orbit

The Artemis 1 mission to the Moon carried 10 CubeSats as secondary payloads. Each CubeSat was developed by a different team with different goals.[31] In another mission, the LICIA CubeSat was carried by the Double Asteroid Redirection Test probe, which launched in November 2021. LICIA assisted DART by monitoring its impact with an asteroid.[32]

See also

- Curiosity rover

- Deep Space 2, another piggyback probe to Mars

- Exploration of Mars

- ExoMars, orbiter and rover

- Mars 3

- Mars Exploration Rover

- Mars Express orbiter

- Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

- Mars Science Laboratory

- 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Mars InSight Launch Press Kit. NASA, 2018.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (9 March 2016). "InSight Mars lander escapes cancellation, aims for 2018 launch". Spaceflight Now. https://spaceflightnow.com/2016/03/09/insight-mars-lander-escapes-cancellation-aims-for-2018-launch/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Good, Andrew; Wendel, JoAnna (4 February 2019). "Beyond Mars, the Mini MarCO Spacecraft Fall Silent". Jet Propulsion Laboratory (NASA). https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=7327.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 MarCO: Planetary CubeSats Become Real. Van Kane, The Planetary Society. 8 July 2015.

- ↑ Stirone, Shannon (18 March 2019). "Space Is Very Big. Some of Its New Explorers Will Be Tiny. - The success of NASA's MarCO mission means that so-called cubesats likely will travel to distant reaches of our solar system.". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/18/science/cubesats-marco-mars.html.

- ↑ Asmar, Sami; Matousek, Steve (20 November 2014). "Mars Cube One (MarCO) - The First Planetary CubeSat Mission". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. https://marscubesatworkshop.jpl.nasa.gov/static/files/presentation/Asmar-Matousek/07-MarsCubeWorkshop-MarCO-update.pdf.

- ↑ Good, Andrew; Johnson, Alana (9 August 2019). "MarCO Wins the 'Oscar' for Tiny Spacecraft". NASA. https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=7475.

- ↑ "RIP, MarCO! The world's first cubesats to Mars are gone for good". 28 February 2020. https://www.space.com/nasa-mars-cubesats-marco-mission-ends.html.

- ↑ Hotz, Robert Lee (November 22, 2018). "Headed to Mars - A Big Experiment in Tiny Satellites: Briefcase-sized CubeSats, commonly used in Earth's orbit, take an interplanetary journey". Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/headed-to-mars-a-big-experiment-in-tiny-satellites-1542891601. "Rapidly approaching Mars are the two smallest and cheapest spacecraft to ever cross between the planets, in the vanguard of what U.S. and European satellite designers hope one day will be swarms of tiny probes prowling the solar system."

- ↑ Hand, Eric (2015-04-10). "Thinking inside the box" (in en). Science 348 (6231): 176–177. doi:10.1126/science.348.6231.176. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25859027.

- ↑ NASA's Mars Cubesats 'Wall-E' and 'Eva' Will Be First at Another Planet. Elizabeth Howell, Space. 1 May 2018.

- ↑ NASA's First Image of Mars from a CubeSat. JPL press release. 22 October 2018

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Big test coming up for tiny satellites trailing Mars lander. Marcia Dunn, PhysOrg. 22 November 2018.

- ↑ Wallace, Mark (May 4, 2018). "The Small Satellites Paving The Way For Low-Cost Exploration Of Deep Space: When NASA's next Mars mission takes off this Saturday, it will be accompanied by two small escorts that could transform the future of space exploration.". Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/40567982/the-small-satellites-paving-the-way-for-low-cost-exploration-of-deep-space. "'The major aspect to MarCO is that it is truly a technology demonstration and high-risk endeavor, very much in the spirit of NASA,' [MarCO chief engineer Andy] Klesh says. 'We see MarCO as only the first in a long line of small satellite explorers . . . .'".

- ↑ Fernholz, Tim (November 26, 2018). "The first interplanetary cubesats pave the way for cheaper space science". Quartz. https://qz.com/1475222/nasa-mars-landing-cubesats-pave-way-for-cheaper-exploration/.

- ↑ "NASA Awards Launch Services Contract for InSight Mission". 19 December 2013. http://www.nasa.gov/press/2013/december/nasa-awards-launch-services-contract-for-insight-mission/.

- ↑ "NASA calls off next Mars mission because of instrument leak". Excite News. Associated Press. 22 December 2015. http://apnews.excite.com/article/20151222/us-sci--mars_lander-de6da5a926.html.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Mars Cube One (MarCO)". https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/cubesat/missions/marco.php.

- ↑ JPL's Advanced CubeSat Concepts for Interplanetary Science and Exploration Missions. (PDF). Sara Spangelo, Julie Castillo-Rogez, Andy Frick, Andy Klesh, Brent Sherwood. CubeSat Workshop 2015. August 2015.

- ↑ NASA's First Deep-Space CubeSats Say: 'Polo!'. NASA News. 6 May 2018

- ↑ "Meet the Tiny Unlikely Hero of the Mars InSight Landing" (in en-US). Popular Mechanics. 2018-11-29. https://www.popularmechanics.com/space/moon-mars/a25336341/small-satellite-insight-mars/.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Hodges, Richard E. (21 February 2017). "A Deployable High-Gain Antenna Bound for Mars: Developing a New Folded-panel Reflectarray for the First CubeSat Mission to Mars.". IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine 59 (2): 39–49. doi:10.1109/MAP.2017.2655561. Bibcode: 2017IAPM...59...39H.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 NASA InSight Team on Course for Mars Touchdown. NASA News. 21 November 2018.

- ↑ Dunn, Marcia (22 November 2018). "Big test coming up for tiny satellites trailing Mars lander". Associated Press. https://www.apnews.com/c121ff6fb2ba45dda7e11cdec2c306d3.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 NASA's InSight Mission Triumphantly Touches Down on Mars. Ian O'Neill, Scientific American. 26 November 2018.

- ↑ How NASA Will Know When InSight Touches Down. Andrew Good, NASA News. 16 November 2018.

- ↑ VACCO - CubeSat Propulsion Systems. VACCO. 2017.

- ↑ "Two Tiny 'CubeSats' Will Watch 2016 Mars Landing". 27 May 2015. https://www.space.com/29489-marco-cubesats-mars-landing-2016.html.

- ↑ MarCO - Mars Cube One. Slide presentation. NASA/JPL. 28 September 2016.

- ↑ NASA's first image of Mars from a CubeSat. Science Daily. 22 October 2018.

- ↑ Hambleton, Kathryn (2 February 2016). "NASA Space Launch System's First Flight to Send Small Sci-Tech Satellites Into Space". https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-space-launch-system-s-first-flight-to-send-small-sci-tech-satellites-into-space.

- ↑ Cheng, Andy (15 November 2018). "DART Mission Update" (PDF). NASA. https://www.cosmos.esa.int/documents/1786001/1845930/4.+DART+Overview+%28A.+Cheng%29.pdf/da9935f1-74b7-9316-e9af-0fb2cc63197c.

External links

- MarsCube One Press kits at JPL

|