Astronomy:Chi Aquilae

| Observation data Equinox J2000.0]] (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Aquila |

| Right ascension | 19h 42m 34.00828s[1] |

| Declination | +11° 49′ 35.7023″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 5.292[2] (5.80 + 6.68)[3] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | G2 Ib-II + B5 V[3] |

| U−B color index | +0.01[4] |

| B−V color index | +0.56[4] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −17.37±0.38[5] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 1.75[1] mas/yr Dec.: −10.11[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 3.82 ± 0.51[1] mas |

| Distance | approx. 900 ly (approx. 260 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −1.53 (−2.1 + −1)[6] |

| Details | |

| Luminosity | 420[7] L☉ |

| Temperature | 5,545[7] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.39±0.10[8] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 3.6[9] km/s |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

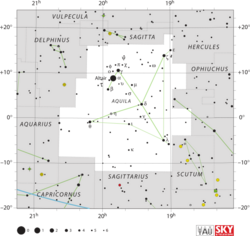

Chi Aquilae is a binary star[3] system in the equatorial constellation of Aquila, the eagle. Its name is a Bayer designation that is Latinized from χ Aquilae, and abbreviated Chi Aql or χ Aql. This system is bright enough to be seen with the naked eye at a combined apparent visual magnitude of +5.29.[2] Based upon parallax measurements made during the Hipparcos mission, Chi Aquilae is at a distance of approximately 900 light-years (280 parsecs) from Earth.[1]

The two components of χ Aquilae can be separated by spectrum and their relative brightness has been measured, but their other properties are uncertain. The cooler component displays an intermediate spectra between a G2 bright giant and a supergiant, and is visually brighter than the hot component, so it is treated as the primary. The hot component has a stellar classification of B5.5V, matching a B-type main-sequence star.[6][3][11]

The absolute magnitude of the primary is −2.1, while that of the secondary is −1. However, the brightness difference between a G2 supergiant and a B5.5 dwarf is expected to be larger. It is unclear whether the primary is not a supergiant or the secondary is brighter than a main-sequence star.[6] As of 2004, the secondary is located at an angular separation of 0.418 arcseconds along a position angle of 76.7° from the primary.[12] The separation and position angle are both decreasing.[13]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007), "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction", Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653–664, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357, Bibcode: 2007A&A...474..653V.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Nordström, B. et al. (May 2004), "The Geneva-Copenhagen survey of the Solar neighbourhood. Ages, metallicities, and kinematic properties of ˜14 000 F and G dwarfs", Astronomy and Astrophysics 418 (3): 989–1019, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20035959, Bibcode: 2004A&A...418..989N.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Eggleton, P. P.; Tokovinin, A. A. (September 2008), "A catalogue of multiplicity among bright stellar systems", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 389 (2): 869–879, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13596.x, Bibcode: 2008MNRAS.389..869E.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Oja, T. (1991), "UBV photometry of stars whose positions are accurately known. VI", Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series 89: 415, Bibcode: 1991A&AS...89..415O.

- ↑ Brown, A. G. A. (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics 616: A1. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Bibcode: 2018A&A...616A...1G. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Ginestet, N.; Carquillat, J. M. (2002), "Spectral Classification of the Hot Components of a Large Sample of Stars with Composite Spectra, and Implication for the Absolute Magnitudes of the Cool Supergiant Components", The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 143 (2): 513, doi:10.1086/342942, Bibcode: 2002ApJS..143..513G.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 McDonald, I. et al. (2012), "Fundamental parameters and infrared excesses of Hipparcos stars", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 427 (1): 343–357, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21873.x, Bibcode: 2012MNRAS.427..343M.

- ↑ Gáspár, András et al. (August 2016), "The Correlation between Metallicity and Debris Disk Mass", The Astrophysical Journal 826 (2): 171, doi:10.3847/0004-637X/826/2/171, ISSN 0004-637X, Bibcode: 2016ApJ...826..171G

- ↑ Ammler-von Eiff, Matthias; Reiners, Ansgar (June 2012), "New measurements of rotation and differential rotation in A-F stars: are there two populations of differentially rotating stars?", Astronomy & Astrophysics 542: A116, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201118724, Bibcode: 2012A&A...542A.116A.

- ↑ "chi Aql". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=chi+Aql.

- ↑ Prieur, J. -L. et al. (February 2003), "Speckle Observations of Composite Spectrum Stars. II. Differential Photometry of the Binary Components", The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 144 (2): 263–276, doi:10.1086/344720, Bibcode: 2003ApJS..144..263P.

- ↑ Scardia, M. et al. (April 2006), "Speckle observations with PISCO in Merate - II. Astrometric measurements of visual binaries in 2004", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 367 (3): 1170–1180, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10035.x, Bibcode: 2006MNRAS.367.1170S.

- ↑ Hartkopf, William I. et al. (2000), "ICCD Speckle Observations of Binary Stars. XXIII. Measurements during 1982-1997 from Six Telescopes, with 14 New Orbits", The Astronomical Journal 119 (6): 3084, doi:10.1086/301402, Bibcode: 2000AJ....119.3084H.

External links

|