Astronomy:Beta Aquilae

| Observation data Equinox J2000.0]] (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Aquila[1] |

| Right ascension | 19h 55m 18.793s[2] |

| Declination | +06° 24′ 24.35″[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 3.87 + 12.0[3] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | G9.5 IV[4] + M2.5 V[5] |

| U−B color index | 0.48[6] |

| B−V color index | 0.86[6] |

| R−I color index | 0.49 |

| Variable type | Suspected |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −40.3±0.09[7] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: +45.944[2] mas/yr Dec.: −480.965[2] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 73.5249 ± 0.1415[8] mas |

| Distance | 44.36 ± 0.09 ly (13.60 ± 0.03 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | +3.03[1] |

| Details[9] | |

| A | |

| Mass | 1.24±0.02 M☉ |

| Radius | 3.096±0.015 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 5.878±0.032[10] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 3.549±0.002 cgs |

| Temperature | 5,090±15[10] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.20±0.04[11] dex |

| Rotation | 5.08697±0.00031[12] days |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 22.28[13] km/s |

| Age | 4.77±0.50 Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| ARICNS | data |

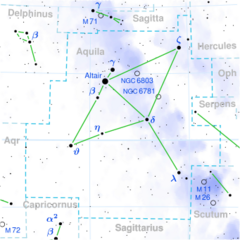

Beta Aquilae is a triple star[15] system in the equatorial constellation of Aquila. Its name is a Bayer designation that is Latinized from β Aquilae, and abbreviated Beta Aql or β Aql. This system is visible to the naked eye as a point-like source with an apparent visual magnitude of 3.87.[3] Based on parallax measurements, it is located at a distance of 44.4 light-years.[8] It is drifting closer to the Sun with a radial velocity of −40 km/s,[7] and is predicted to approach to within 27 light-years (8.4 pc) in roughly 207,000 years.[16]

Its two visible components are designated Beta Aquilae A and B. The former is formally named Alshain /ælˈʃeɪn/, the traditional name for the system.[17][18]

Nomenclature

β Aquilae (Latinised to Beta Aquilae) is the system's Bayer designation. The designations of the two components as Beta Aquilae A and B derive from the convention used by the Washington Multiplicity Catalog (WMC) for multiple star systems, and adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).[19]

The system bore the traditional name Alshain derived from the Perso-Arabic term الشاهين, aš-šāhīn, meaning "the (peregrine) falcon", perhaps by folk etymology from the Persian šāhīn tarāzū (or possibly šāhīn tara zed; see Gamma Aquilae), the Persian name for the asterism α, β and γ Aquilae.[citation needed] In 2016, the IAU organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[20] to catalogue and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN decided to attribute proper names to individual stars rather than entire multiple systems.[21] It approved the name Alshain for the component Beta Aquilae A on 21 August 2016 and it is now so included in the List of IAU-approved Star Names.[18]

In the catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of Al Achsasi al Mouakket, this star was designated Unuk al Ghyrab (عنق ألغراب - únuq al-ghuraab), which was translated into Latin as Collum Corvi, meaning the crow's neck.[22]

In Chinese, 河鼓 (Hé Gŭ), meaning River Drum, refers to an asterism consisting of Beta Aquilae, Altair and Gamma Aquilae.[23] Consequently, the Chinese name for Beta Aquilae itself is 河鼓一 (Hé Gŭ yī, English: the First Star of River Drum).[24]

Properties

The primary, component A, is of magnitude 3.71 and spectral class G8IV. It has a very low level of surface magnetic activity and may be in a state similar to a Maunder minimum.[25] The activity shows a cycle of 969±27 d.[12] The star displays solar-like oscillations.[26] Since 1943, the spectrum of this star has served as one of the stable anchor points by which other stars are classified.[27]

This is an aging subgiant star that has exhausted the supply of hydrogen at its core and is evolving into a giant.[12] Its angular diameter has been precisely determined using interferometry at the Very Large Telescope and the CHARA array, the average of both measurements, combined with its estimated distance, result in a radius 3.096 times the radius of the Sun. It has a mass 24% greater than the Sun's,[9] a luminosity 5.9 times that of the Sun, and an effective temperature of 5,060 K.[10]

The 12th magnitude secondary companion, designated component B, is a double-lined spectroscopic binary,[28] which is at an angular separation of 13 arcseconds from the primary. It has a stellar classification of M2.5 V,[5] matching a class M red dwarf.

In culture

In the Chinese folk tale The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, Beta and Gamma Aquilae are children of Niulang (牛郎, The Cowherd, Altair) and Zhinü (織女, The Princess, Vega).

The Koori people of Victoria knew Beta and Gamma Aquilae as the black swan wives of Bunjil (Altair), the wedge-tailed eagle.[29]

missing name was a United States Navy ship.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012), "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation", Astronomy Letters 38 (5): 331, doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015, Bibcode: 2012AstL...38..331A.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Vallenari, A. et al. (2022). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940 Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Eggleton, P. P.; Tokovinin, A. A. (2008), "A catalogue of multiplicity among bright stellar systems", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 389 (2): 869, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13596.x, Bibcode: 2008MNRAS.389..869E.

- ↑ Gray, R. O. et al. (July 2006), "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: spectroscopy of stars earlier than M0 within 40 pc-The Southern Sample", The Astronomical Journal 132 (1): 161–170, doi:10.1086/504637, Bibcode: 2006AJ....132..161G.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Montes, D. et al. (September 2018), "Calibrating the metallicity of M dwarfs in wide physical binaries with F-, G-, and K-primaries - I: High-resolution spectroscopy with HERMES: stellar parameters, abundances, and kinematics", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 479 (1): 1332–1382, doi:10.1093/mnras/sty1295, Bibcode: 2018MNRAS.479.1332M.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Oja, T. (August 1986), "UBV photometry of stars whose positions are accurately known. III", Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series 65 (2): 405–4, Bibcode: 1986A&AS...65..405O.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Jofré, E. et al. (February 2015), "Stellar parameters and chemical abundances of 223 evolved stars with and without planets", Astronomy & Astrophysics 574: 46, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424474, A50, Bibcode: 2015A&A...574A..50J.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 van Leeuwen, F. (2007), "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction", Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653–664, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357, Bibcode: 2007A&A...474..653V.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kjeldsen, Hans et al. (2025). "Asteroseismology of the G8 subgiant β Aquilae with SONG-Tenerife, SONG-Australia and TESS". Astronomy & Astrophysics 700: A39. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202554633. Bibcode: 2025A&A...700A..39K.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Soubiran, C. et al. (February 1, 2024), "Gaia FGK benchmark stars: Fundamental Teff and log g of the third version", Astronomy and Astrophysics 682: A145, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202347136, ISSN 0004-6361, Bibcode: 2024A&A...682A.145S

- ↑ Karovicova, I. et al. (February 2022), "Fundamental stellar parameters of benchmark stars from CHARA interferometry -- III. Giant and subgiant stars", Astronomy & Astrophysics 658: A48, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202142100, ISSN 0004-6361, Bibcode: 2022A&A...658A..48K

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Butkovskaya, Varvara et al. (February 2018), "Long-term stellar magnetic field study at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory", Long-term Datasets for the Understanding of Solar and Stellar Magnetic Cycles, Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, IAU Symposium 340: pp. 35–38, doi:10.1017/S1743921318001035, Bibcode: 2018IAUS..340...35B.

- ↑ Rains, Adam D. et al. (April 2020), "Precision angular diameters for 16 southern stars with VLTI/PIONIER", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 493 (2): 2377–2394, doi:10.1093/mnras/staa282, Bibcode: 2020MNRAS.493.2377R

- ↑ "bet Aql". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=bet+Aql.

- ↑ Fuhrmann, K. et al. (February 2017), "Multiplicity among Solar-type Stars", The Astrophysical Journal 836 (1): 23, doi:10.3847/1538-4357/836/1/139, 139, Bibcode: 2017ApJ...836..139F.

- ↑ Bailer-Jones, C. A. L. (March 2015), "Close encounters of the stellar kind", Astronomy & Astrophysics 575: 13, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201425221, A35, Bibcode: 2015A&A...575A..35B.

- ↑ Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006), A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations (2nd rev. ed.), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Pub, ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Naming Stars, IAU.org, https://www.iau.org/public/themes/naming_stars/, retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ↑ Hessman, F. V.; et al. (2010). "On the naming convention used for multiple star systems and extrasolar planets". arXiv:1012.0707 [astro-ph.SR].

- ↑ IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN), International Astronomical Union, https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/, retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ WG Triennial Report (2015-2018) - Star Names, p. 5, https://www.iau.org/static/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/wg-starnames-triennial-report-2015-2018.pdf, retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ↑ Knobel, E. B. (June 1895), "Al Achsasi Al Mouakket, on a catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of Mohammad Al Achsasi Al Mouakket", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 55: 429–438, doi:10.1093/mnras/55.8.429, Bibcode: 1895MNRAS..55..429K.

- ↑ (in Chinese) 中國星座神話, written by 陳久金. Published by 台灣書房出版有限公司, 2005, ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ↑ (in Chinese) 香港太空館 - 研究資源 - 亮星中英對照表 , Hong Kong Space Museum. Accessed on line November 26, 2008.

- ↑ Andretta, V. et al. (February 2005), "The Ca II Infrared Triplet as a stellar activity diagnostic . I. Non-LTE photospheric profiles and definition of the RIRT indicator", Astronomy and Astrophysics 430 (2): 669–677, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041745, Bibcode: 2005A&A...430..669A.

- ↑ Corsaro, E. et al. (January 2012), "Solar-like oscillations in the G9.5 subgiant β Aquilae", Astronomy & Astrophysics 537: id. A9, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117158, Bibcode: 2012A&A...537A...9C.

- ↑ Garrison, R. F. (December 1993), "Anchor Points for the MK System of Spectral Classification", Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 25: 1319, Bibcode: 1993AAS...183.1710G, http://www.astro.utoronto.ca/~garrison/mkstds.html, retrieved 2012-02-04

- ↑ Bonfils, Xavier et al. (2005), "Metallicity of M dwarfs. I. A photometric calibration and the impact on the mass-luminosity relation at the bottom of the main sequence", Astronomy and Astrophysics 442 (2): 635–642, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053046, Bibcode: 2005A&A...442..635B, http://cdsads.u-strasbg.fr/cgi-bin/nph-bib_query?2005A%26A...442..635B&db_key=AST&nosetcookie=1.

- ↑ Mudrooroo (1994), Aboriginal mythology : an A-Z spanning the history of aboriginal mythology from the earliest legends to the present day, London: HarperCollins, p. 4, ISBN 1-85538-306-3.

External links

- Kaler, James B., "ALSHAIN (Beta Aquilae)", Stars (University of Illinois), http://stars.astro.illinois.edu/sow/alshain.html, retrieved 2018-03-03

- ARICNS

- Beta Aquilae by Professor Jim Kaler.

- Image β Aquilae

- [1] Stellar Catalog entry for Beta Aquilae.

|