Astronomy:Gamma Centauri

Script error: No such module "About-distinguish".

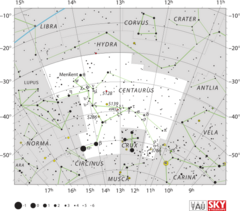

Gamma Centauri is a binary star system in the southern constellation of Centaurus, which is probably part of a wider system together with Tau Centauri. The system is visible to the naked eye as a single point of light with a combined apparent visual magnitude of +2.17;[2] individually they are third-magnitude stars.[3]

Nomenclature

Its main name is a Bayer designation that is Latinized from γ Centauri, and abbreviated Gamma Cen or γ Cen.

It has the proper name Muhlifain,[10] not to be confused with Muliphein, which is γ Canis Majoris; both names derive from the same Arabic root.

Characteristics

This system is located at a distance of about 130 light-years (40 parsecs) from the Sun based on parallax. In 2000, the pair had an angular separation of 1.217 arcseconds with a position angle of 351.9°.[3] Their positions have been observed since 1897, which is long enough to estimate an orbital period of 84.5 years and a semimajor axis of 0.93 arcsecond.[11][8] At the distance of this system, this is equivalent to a physical separation of about 93 astronomical unit|AU.[9]

The stars have spectral types of A1IV and A0IV,[5] suggesting they are A-type subgiant stars in the process of becoming giants. The stars have similar characteristics, with an estimated 2.8 times the Sun's mass, around 100 times the Sun's luminosity and an estimated effective temperature of 9,300 K.[9]

The star Tau Centauri very likely makes a widely-separated binary system with Gamma Centauri, it is a co-moving star with an estimated separation of 1.72 light-years (0.53 parsecs). There is a 98% chance that they are gravitationally bound.[12]

Etymology

In Chinese astronomy, 庫樓 (Kù Lóu), meaning Arsenal, refers to an asterism consisting of γ Centauri, ζ Centauri, η Centauri, θ Centauri, 2 Centauri, HD 117440, ξ1 Centauri, τ Centauri, D Centauri and σ Centauri.[13] Consequently, the Chinese name for γ Centauri itself is 庫樓七 (Kù Lóu qī, English: the Seventh Star of Arsenal).[14]

The people of Aranda and Luritja tribe around Hermannsburg, Central Australia named a quadrangular arrangement comprising this star, δ Cen (Ma Wei), δ Cru (Imai) and γ Cru (Gacrux) as Iritjinga ("The Eagle-hawk").[15]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Calculated, using the Stefan-Boltzmann law and the star's effective temperature and luminosity, with respect to the solar nominal effective temperature of 5,772 K:

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653–664. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. Bibcode: 2007A&A...474..653V.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Johnson, H. L. et al. (1966). "UBVRIJKL photometry of the bright stars". Communications of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory 4 (99): 99. Bibcode: 1966CoLPL...4...99J.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Fabricius, C.; Makarov, V. V. (April 2000). "Two-colour photometry for 9473 components of close Hipparcos double and multiple stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics 356: 141–145. Bibcode: 2000A&A...356..141F.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gray, R. O. et al. (July 2006). "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: Spectroscopy of Stars Earlier than M0 within 40 pc-The Southern Sample". The Astronomical Journal 132 (1): 161–170. doi:10.1086/504637. Bibcode: 2006AJ....132..161G.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gray, R. O.; Garrison, R. F. (December 1987). "The Early A-Type Stars: Refined MK Classification, Confrontation with Stroemgren Photometry, and the Effects of Rotation". Astrophysical Journal Supplement 65: 581. doi:10.1086/191237. Bibcode: 1987ApJS...65..581G.

- ↑ Evans, D. S. (June 20–24, 1966). "The Revision of the General Catalogue of Radial Velocities". Determination of Radial Velocities and Their Applications, Proceedings from IAU Symposium No. 30 (University of Toronto: International Astronomical Union) 30: 57. Bibcode: 1967IAUS...30...57E.

- ↑ Schaaf, Fred (2008). The brightest stars: discovering the universe through the sky's most brilliant stars. John Wiley and Sons. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-471-70410-2. Bibcode: 2008bsdu.book.....S.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Argyle, R. W. et al. (May 2015). "Micrometric measures and orbits of southern visual double stars". Astronomische Nachrichten 336 (4): 378–387. doi:10.1002/asna.201412166. Bibcode: 2015AN....336..378A.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Kaler, James B.. "MUHLIFAIN (Gamma Centauri)". Stars. University of Illinois. http://stars.astro.illinois.edu/sow/muhlifain.html.

- ↑ Paul Kunitzsch (1959). Arabische Sternnamen in Europa, von Paul Kunitzsch. O. Harrassowitz. p. 188. https://books.google.com/books?id=qhtGQwAACAAJ.

- ↑ Mason, Brian D. et al. (December 2001). "The 2001 US Naval Observatory Double Star CD-ROM. I. The Washington Double Star Catalog". The Astronomical Journal 122 (6): 3466–3471. doi:10.1086/323920. Bibcode: 2001AJ....122.3466M.

- ↑ Shaya, Ed J.; Olling, Rob P. (January 2011). "Very Wide Binaries and Other Comoving Stellar Companions: A Bayesian Analysis of the Hipparcos Catalogue". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement 192 (1): 2. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/192/1/2. Bibcode: 2011ApJS..192....2S.

- ↑ (in Chinese) 中國星座神話, written by 陳久金. Published by 台灣書房出版有限公司, 2005, ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ↑ (in Chinese) 香港太空館 - 研究資源 - 亮星中英對照表 , Hong Kong Space Museum. Accessed online November 23, 2010.

- ↑ Raymond Haynes; Roslynn D. Haynes; David Malin; Richard McGee (1996), Explorers of the Southern Sky: A History of Australian Astronomy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 8, ISBN 978-0-521-36575-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=XoeiJxMmXZ8C

|