Astronomy:HD 129116

| Observation data Equinox J2000.0]] (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

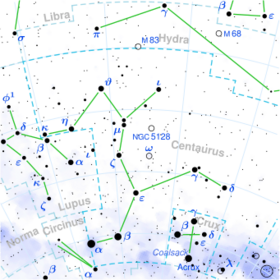

| Constellation | Centaurus[1] |

| Right ascension | 14h 41m 57.59068s[2] |

| Declination | −37° 47′ 36.5940″[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | +4.01[1] |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | Main sequence |

| Spectral type | B3V[3] |

| B−V color index | −0.157±0.002[1] |

| Variable type | Constant[4] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | +2.6±1.5[1] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −29.828±0.369[5] mas/yr Dec.: −31.914±0.518[5] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 10.0339 ± 0.3143[5] mas |

| Distance | 330 ± 10 ly (100 ± 3 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −1.07[1] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 5–6[6] M☉ |

| Radius | 2.93±0.12[7] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 637.01[1] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.23±0.03[7] cgs |

| Temperature | 18,310±320[6] K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 129[8] km/s |

| Age | 15±2[6] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

HD 129116 is a binary star in the northeastern part of Centaurus, east of Menkent. It is also known by its Bayer designation of b Centauri, while HD 129116 is the star's identifier in the Henry Draper catalogue. This object has a blue-white hue and is faintly visible to the naked eye with an apparent visual magnitude of +4.01.[1] It is located at a distance of approximately 325 light years (100 parsecs)[5] from the Sun based on parallax, and has an absolute magnitude of −1.07.[1]

The primary star is a hot type-B star with a spectral type of B3V and a mass of 5 to 6 times the solar mass. The secondary star is a close companion separated by approximately 1 AU, with up to 4.4 times the solar mass. In 2021, a massive exoplanet was discovered by direct imaging orbiting the pair of stars (a circumbinary planet) at a distance of about 560 AU.[6]

Star system

This is a young stellar system, belonging to the Upper Centaurus–Lupus subgroup of the Scorpius–Centaurus association, the nearest OB association to the Sun. This is an association of stars with common origin and movement.[10] The region inside Upper Centaurus–Lupus where b Centauri is located seems to have a uniform age of 15 million years, which is therefore the age of this system (with an uncertainty of about 2 million years).[6] From its stellar parallax measured by the Gaia spacecraft, b Centauri is located at a distance of 325 light years (100 parsecs).[5] It has been noted that the secondary star may interfere with the parallax measurements, so this distance value may not be completely accurate. In any case, b Centauri seems to be located on the closer side of the Scorpius–Centaurus association, as seen from Earth, which is also indicated by its higher proper motion compared to the mean of the association.[6]

The primary star, b Centauri A, is a B-type main-sequence star with a stellar classification of B3V,[3] which indicates it is engaged in core hydrogen fusion to generate energy. The object has been used as a "standard star" in several photometric systems, and it appears to be non-variable.[4] It has a high rate of spin, showing a projected rotational velocity of 129 km/s.[8] The star has 5 to 6[6] times the mass of the Sun and 2.9[7] times the Sun's radius. It is radiating 637[1] times the luminosity of the Sun from its photosphere at an effective temperature of 18,445 K.[7]

In 1968 the primary was found to have variable radial velocity, which is evidence of a second star in the system, but no orbit was published.[11] The existence of the secondary star, b Centauri B, was confirmed in 2010 with an interferometric observation, which revealed it at a separation of 9.22 mas, or 1.0 astronomical unit|AU at the system's distance.[12] The difference in magnitude between the stars is 1.06,[12] from which a mass of 4.4 M☉ is calculated for the secondary. However this value for the magnitude difference is uncertain, since it was based on a single observation and the detection is close to the instrument performance limit, so the mass of 4.4 M☉ is considered an upper estimate.[6] Given all uncertainties, the total mass of the system is estimated at 6 to 10 M☉.[6]

Planetary system

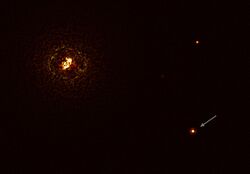

The b Centauri system was included in the BEAST survey, which uses the SPHERE instrument at the Very Large Telescope to search for planets around B-type stars in the Scorpius–Centaurus association. SPHERE is equipped with a sophisticated coronagraph that blocks out the light from a star and allows exoplanets around it to be directly imaged.[13] The first observation of the system in 2019 revealed an object at a 5.3 arcseconds separation that had infrared colors consistent with a massive planet. A second observation in 2021 confirmed that the object has common proper motion with b Centauri and therefore is physically bound to the system.[6] The authors of this study also looked for old observations of b Centauri and found that the planet had been imaged by the ESO 3.6 m Telescope in 2000, but was considered a background star at the time.[6][14] With a primary star mass of 5–6 M☉ and a total system mass of 6–10 M☉, b Centauri is the most massive system around which a planet has been found; previously, the most massive star with a known planet was 3 M☉. The discovery was published in December 2021 on the scientific journal Nature and was led by Stockholm University astronomer Markus Janson.[6]

Named b Centauri (AB)b (shortened as 'b Cen (AB)b'), this is a circumbinary planet that orbits the stellar pair at a projected separation of 560 AU. The three epochs of observations show evidence of the orbital motion of the planet around the central stars, but the orbit is still not well constrained. The data are consistent with an orbital period between 2650 and 7170 years, inclination between 128 and 157 degrees, and eccentricity smaller than 0.4.[6]

The SPHERE images show the planet has approximately 0.01% the solar luminosity, a relic of its recent formation. From this luminosity and the age of the system, cooling models predict it has a mass of about 11 times the mass of Jupiter. The mass ratio between b Cen (AB)b and the central binary star is 0.10—0.17%, which is similar to the Sun-Jupiter system and is consistent to the expectations that more massive stars tend to have more massive planets.[6]

The formation mechanism for b Cen (AB)b is uncertain. It is believed that most giant planets are formed via core accretion, in which a rocky core, after growing to a critical mass, starts rapidly accreting the surrounding gas of the circumstellar disc. This mechanism cannot explain b Cen (AB)b, because core accretion becomes less efficient at large distances from the star, and massive stars like b Centauri A cause the disc to dissipate much quicker. It's more probable that the planet formed directly from the circumstellar gas, through a mechanism known as gravitational instability. This process is much faster than core accretion and can act even at separations of hundreds of astronomical units. Another possibility is that the planet formed closer to the central stars and was subsequently ejected to its current orbit through interactions with another body, but this is disfavored by the lack of evidence of other planets in the system and by the low eccentricity of b Cen (AB)b.[6]

The discovery of b Cen (AB)b showed that planets can exist even around massive stars. Previous studies had shown that planet occurrence rate starts to drop for stars over 2 M☉ and reaches almost zero for 3 M☉ stars, but this result is valid only for close in planets, which the radial velocity method can detect. The discovers of b Cen (AB)b argued that the short lifetime of the circumstellar discs around massive stars may prevent planets from migrating closer to their stars, but allows the existence of distant planets like b Cen (AB)b.[6]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (years) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (AB)b | 10.9±1.6 MJ | 556±17 | 2650–7170 | <0.40 | 128–157° | — |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012). "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation". Astronomy Letters 38 (5): 331. doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015. Bibcode: 2012AstL...38..331A XHIP record for this object at VizieR.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653–664. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. Bibcode: 2007A&A...474..653V.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hiltner, W. A. et al. (July 1969). "MK Spectral Types for Bright Southern OB Stars". Astrophysical Journal 157: 313–326. doi:10.1086/150069. Bibcode: 1969ApJ...157..313H.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Paunzen, E.; Rode-Paunzen, M. (2017). "BRITE photometry of seven B-type stars". Second Brite-Constellation Science Conference: Small Satellites – Big Science 5: 180. Bibcode: 2017sbcs.conf..180P.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Brown, A. G. A. (2021). "Gaia Early Data Release 3: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics 649: A1. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657. Bibcode: 2021A&A...649A...1G. Gaia EDR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Janson, Markus; Gratton, Raffaele; Rodet, Laetitia; Vigan, Arthur; Bonnefoy, Mickaël; Delorme, Philippe; Mamajek, Eric E.; Reffert, Sabine et al. (2021). "A wide-orbit giant planet in the high-mass b Centauri binary system". Nature 600 (7888): 231–234. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04124-8. PMID 34880428. Bibcode: 2021Natur.600..231J.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Fitzpatrick, E. L.; Massa, D. (March 2005). "Determining the Physical Properties of the B Stars. II. Calibration of Synthetic Photometry". The Astronomical Journal 129 (3): 1642–1662. doi:10.1086/427855. Bibcode: 2005AJ....129.1642F.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Wolff, S. C.; Strom, S. E.; Dror, D.; Venn, K. (2007). "Rotational Velocities for B0-B3 Stars in Seven Young Clusters: Further Study of the Relationship between Rotation Speed and Density in Star-Forming Regions". The Astronomical Journal 133 (3): 1092–1103. doi:10.1086/511002. Bibcode: 2007AJ....133.1092W.

- ↑ "b Cen". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=b+Cen.

- ↑ De Zeeuw, P. T.; Hoogerwerf, R.; De Bruijne, J. H. J.; Brown, A. G. A.; Blaauw, A. (1999). "A HIPPARCOS Census of the Nearby OB Associations". The Astronomical Journal 117 (1): 354–399. doi:10.1086/300682. Bibcode: 1999AJ....117..354D.

- ↑ Gutierrez-Moreno, Adelina; Moreno, Hugo (1968). "A Photometric Investigation of the SCORPIUS-CENTAURUS Association". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 15: 459. doi:10.1086/190168. Bibcode: 1968ApJS...15..459G.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Rizzuto, A. C.; Ireland, M. J.; Robertson, J. G.; Kok, Y.; Tuthill, P. G.; Warrington, B. A.; Haubois, X.; Tango, W. J. et al. (2013). "Long-baseline interferometric multiplicity survey of the Sco-Cen OB association". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 436 (2): 1694. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1690. Bibcode: 2013MNRAS.436.1694R.

- ↑ Janson, Markus; Squicciarini, Vito; Delorme, Philippe; Gratton, Raffaele; Bonnefoy, Mickaël; Reffert, Sabine; Mamajek, Eric E.; Eriksson, Simon C. et al. (2021). "BEAST begins: Sample characteristics and survey performance of the B-star Exoplanet Abundance Study". Astronomy and Astrophysics 646: A164. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039683. Bibcode: 2021A&A...646A.164J.

- ↑ Shatsky, N.; Tokovinin, A. (2002). "The mass ratio distribution of B-type visual binaries in the Sco OB2 association". Astronomy and Astrophysics 382: 92. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011542. Bibcode: 2002A&A...382...92S.

External links

- "ESO telescope images planet around most massive star pair to date". European Southern Observatory. 8 December 2021. https://www.eso.org/public/news/eso2118/.

|