Astronomy:HR 8799

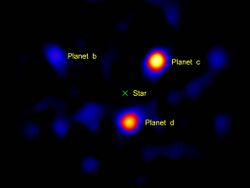

300px HR 8799 (marked with star) with HR 8799 e (upper right), HR 8799 d (lower right), HR 8799 c (up from HR 8799 e) and HR 8799 b (left) as of 2025 from James Webb Space Telescope | |

| Observation data Equinox J2000.0]] (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Pegasus |

| Right ascension | 23h 07m 28.7157s[1] |

| Declination | +21° 08′ 03.311″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 5.964[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | kA5 hF0 mA5 V; λ Boo[3][4] |

| U−B color index | −0.04[5] |

| B−V color index | 0.234[2] |

| Variable type | Gamma Doradus variable[2] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −11.5±2[2] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 108.284±0.056[1] mas/yr Dec.: −50.040±0.059[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 24.4620 ± 0.0455[1] mas |

| Distance | 133.3 ± 0.2 ly (40.88 ± 0.08 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 2.98±0.08[3] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.43+0.06 −0.07[6] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.44±0.06[7] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 5.05±0.29[7] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.35±0.05[3] cgs |

| Temperature | 7,193±87[7] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.52±0.08[8][lower-alpha 1] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 37.5±2[3] km/s |

| Age | 42+24 −16[9] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| Exoplanet Archive | 8799 data |

| Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia | data |

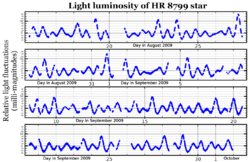

HR 8799 is a roughly 30 million-year-old main-sequence star located 133.3 light-years (40.9 parsecs) away from Earth in the constellation of Pegasus. It has roughly 1.5 times the Sun's mass and 4.9 times its luminosity. It is part of a system that also contains a debris disk and at least four massive planets. These planets were the first exoplanets whose orbital motion was confirmed by direct imaging. The star is a Gamma Doradus variable: its luminosity changes because of non-radial pulsations of its surface. The star is also classified as a Lambda Boötis star, which means its surface layers are depleted in iron peak elements. It is the only known star which is simultaneously a Gamma Doradus variable, a Lambda Boötis type, and a Vega-like star (a star with excess infrared emission caused by a circumstellar disk).

Location

HR 8799 is a star that is visible to the naked eye. It has a magnitude 5.96 and it is located inside the western edge of the great square of Pegasus almost exactly halfway between Beta and Alpha Pegasi. The star's name of HR 8799 is its line number in the Bright Star Catalogue.

Stellar properties

The star HR 8799 is a member of the Lambda Boötis (λ Boo) class, a group of peculiar stars with an unusual lack of "metals" (elements heavier than hydrogen and helium) in their upper atmosphere. Because of this special status, stars like HR 8799 have a very complex spectral type. The luminosity profile of the Balmer lines in the star's spectrum, as well as the star's effective temperature, best match the typical properties of an F0 V star. However, the strength of the calcium II K absorption line and the other metallic lines are more like those of an A5 V star. The star's spectral type is therefore written as kA5 hF0 mA5 V; λ Boo.[3][4]

Age determination of this star shows some variation based on the method used. Statistically, for stars hosting a debris disk, the luminosity of this star suggests an age of about 20–150 million years. Comparison with stars having similar motion through space gives an age in the range 30–160 million years. Given the star's position on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram of luminosity versus temperature, it has an estimated age in the range of 30–1,128 million years. λ Boötis stars like this are generally young, with a mean age of a billion years. More accurately, asteroseismology also suggests an age of approximately a billion years.[11] However, this is disputed because it would make the planets become brown dwarfs to fit into the cooling models. Brown dwarfs would not be stable in such a configuration. The best accepted value for an age of HR 8799 is 30 million years, consistent with being a member of the Columba association co-moving group of stars.[12]

Earlier analysis of the star's spectrum reveals that it has a slight overabundance of carbon and oxygen compared to the Sun (by approximately 30% and 10% respectively). While some Lambda Boötis stars have sulfur abundances similar to that of the Sun, this is not the case for HR 8799; the sulfur abundance is only around 35% of the solar level. The star is also poor in elements heavier than sodium: for example, the iron abundance is only 28% of the solar iron abundance.[13] Asteroseismic observations of other pulsating Lambda Boötis stars suggest that the peculiar abundance patterns of these stars are confined to the surface only: the bulk composition is likely more normal. This may indicate that the observed element abundances are the result of the accretion of metal-poor gas from the environment around the star.[14]

In 2020, spectral analysis using multiple data sources have detected an inconsistency in prior data and concluded the star carbon and oxygen abundances are the same or slightly higher than solar. The iron abundance was updated to 30+6−5% of solar value.[8]

Astroseismic analysis using spectroscopic data indicates that the rotational inclination of the star is constrained to be greater than or approximately equal to 40°. This contrasts with the planets' orbital inclinations, which are in roughly the same plane at an angle of about 20° ± 10°. Hence, there may be an unexplained misalignment between the rotation of the star and the orbits of its planets.[15] Observation of this star with the Chandra X-ray Observatory indicates that it has a weak level of magnetic activity, but the X-ray activity is much higher than that of an A‑type star like Altair. This suggests that the internal structure of the star more closely resembles that of an F0 star. The temperature of the stellar corona is about 3.0 million K.[16]

Planetary system

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (years) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f [22] (unconfirmed) | 4–7 MJ | 4.325 | — | 0.0686 | — | — |

| Dust disk | 15±5[23] AU | — | — | |||

| e | 9.6+1.9 −1.8 MJ |

16.25±0.04 | ~45 | 0.1445±0.0013 | 25 ± 8° | 1.17+0.13 −0.11 RJ |

| d | 9.2±0.1 MJ | 26.67±0.08 | ~100 | 0.1134±0.0011 | 28° | 1.2±0.1 RJ |

| c | 8.5±0.4 MJ | 41.39±0.11 | ~190 | 0.0519±0.0022 | 28° | 1.2±0.1 RJ |

| b | 6.0±0.3 MJ | 71.6±0.2 | ~460 | 0.016±0.001 | 28° | 1.2±0.1 RJ |

| Dust disk | 135–360[24] AU | — | — | |||

On 13 November 2008, Christian Marois of the National Research Council of Canada's Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics and his team announced they had directly observed three planets orbiting the star with the Keck and Gemini telescopes in Hawaii,[25][26][27][28] in both cases employing adaptive optics to make observations in the infrared.[lower-alpha 2] A precovery observation of the outer 3 planets was later found in infrared images obtained in 1998 by the Hubble Space Telescope's NICMOS instrument, after a newly developed image-processing technique was applied.[29] Further observations in 2009–2010 revealed the fourth giant planet orbiting inside the first three planets at a projected separation just less than 15 AU,[17][30] which has been confirmed by multiple studies.[31]

HR 8799 b orbits inside a dusty disk like the Solar Kuiper belt. It is one of the most massive disks known around any star within 300 light years of Earth, and there is room in the inner system for terrestrial planets.[32] There is an additional debris disk just inside the orbit of the innermost planet.[17]

The orbital radii of planets e, d, c, and b are 2–3 times those of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune's orbits, respectively. Because of the inverse square law relating radiation intensity to distance from the source, comparable radiation intensities are present at distances √4.9 ≈ 2.2 times farther from HR 8799 than from the Sun, it serendipitously turns out that corresponding planets in the solar and HR 8799 systems receive similar amounts of stellar radiation.[17]

These objects are near the upper mass limit for classification as planets; if they exceeded 13 Jupiter masses, they would be capable of (but not guaranteed to exhibit) deuterium fusion in their interiors and thus qualify as brown dwarfs under the definition of these terms used by the IAU's Working Group on Extrasolar Planets.[33] If the mass estimates are correct, the HR 8799 system is the first multiple-planet extrasolar system to be directly imaged.[26] The orbital motion of the planets is in an anticlockwise direction and was confirmed via multiple observations dating back to 1998.[25] The system is more likely to be stable if the planets e, d, and c are in a 4:2:1 resonance, which would imply that the orbit of the planet d has an eccentricity exceeding 0.04 in order to match the observational constraints. Planetary systems with the best-fit masses from evolutionary models would be stable if the outer three planets are in a 1:2:4 orbital resonance (similar to the Laplace resonance between Jupiter's inner three Galilean satellites: Io, Europa, and Ganymede as well as three of the planets in the Gliese 876 system).[17] However, it is disputed if planet b is in resonance with the other 3 planets. According to dynamical simulations, the HR 8799 planetary system may be even an extrasolar system with multiple resonance 1:2:4:8.[20] The 4 young planets are still glowing red hot from the heat of their formation and are larger than Jupiter; over time they will cool and shrink to sizes of 0.8–1.0 Jupiter radii.

The broadband photometry of planets b, c and d has shown that there may be significant clouds in their atmospheres,[30] while the infrared spectroscopy of planets b and c points to non-equilibrium CO / CH

4 chemistry.[17] Near-infrared observations with the Project 1640 integral field spectrograph on the Palomar Observatory have shown that compositions between the four planets vary significantly. This is a surprise since the planets presumably formed in the same way from the same disk and have similar luminosities.[34]

An additional planet candidate was found in cycle 1 with NIRCam, 5 arcseconds south of HR 8799. Follow-up observations with NIRCam are planned to confirm or reject this candidate.[35]

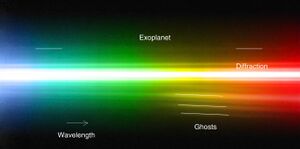

Planet spectra

A number of studies have used the spectra of HR 8799's planets to determine their chemical compositions and constrain their formation scenarios. The first spectroscopic study of planet b (performed at near-infrared wavelengths) detected strong water absorption and hints of methane absorption.[36] Subsequently, weak methane and carbon monoxide absorption in this planet's atmosphere was also detected, indicating efficient vertical mixing of the atmosphere and a disequilibrium CO / CH

4 ratio at the photosphere. Compared to models of planetary atmospheres, this first spectrum of planet b is best matched by a model of enhanced metallicity (about 10 times the metallicity of the Sun), which may support the notion that this planet formed through core-accretion.[37]

The first simultaneous spectra of all four known planets in the HR 8799 system were obtained in 2012 using the Project 1640 instrument at Palomar Observatory. The near-infrared spectra from this instrument confirmed the red colors of all four planets and are best matched by models of planetary atmospheres that include clouds. Though these spectra do not directly correspond to any known astrophysical objects, some of the planet spectra demonstrate similarities with L- and T-type brown dwarfs and the night-side spectrum of Saturn. The implications of the simultaneous spectra of all four planets obtained with Project 1640 are summarized as follows: Planet b contains ammonia and/or acetylene as well as carbon dioxide, but has little methane; planet c contains ammonia, perhaps some acetylene but neither carbon dioxide nor substantial methane; planet d contains acetylene, methane, and carbon dioxide but ammonia is not definitively detected; planet e contains methane and acetylene but no ammonia or carbon dioxide. The spectrum of planet e is similar to a reddened spectrum of Saturn.[34]

Moderate-resolution near-infrared spectroscopy, obtained with the Keck telescope, definitively detected carbon monoxide and water absorption lines in the atmosphere of planet c. The carbon-to-oxygen ratio, which is thought to be a good indicator of the formation history for giant planets, for planet c was measured to be slightly greater than that of the host star HR 8799. The enhanced carbon-to-oxygen ratio and depleted levels of carbon and oxygen in planet c favor a history in which the planet formed through core accretion.[38] However, it is important to note that conclusions about the formation history of a planet based solely on its composition may be inaccurate if the planet has undergone significant migration, chemical evolution, or core dredging.[clarification needed] Later, in November 2018, researchers confirmed the existence of water and the absence of methane in the atmosphere of HR 8799 c using high-resolution spectroscopy and near-infrared adaptive optics (NIRSPAO) at the Keck Observatory.[39][40]

The red colors of the planets may be explained by the presence of iron and silicate atmospheric clouds, while their low surface gravities might explain the strong disequilibrium concentrations of carbon monoxide and the lack of strong methane absorption.[38]

Debris disk

In January 2009 the Spitzer Space Telescope obtained images of the debris disk around HR 8799. Three components of the debris disk were distinguished:

- Warm dust (T ≈ 150 K) orbiting within the innermost planet (e). The inner and outer edges of this belt are close to 4:1 and 2:1 resonances with the planet.[17]

- A broad zone of cold dust (T ≈ 45 K) with a sharp inner edge orbiting just outside the outermost planet (b). The inner edge of this belt is approximately in 3:2 resonance with said planet, similar to Neptune and the Kuiper belt.[17]

- A dramatic halo of small grains originating in the cold dust component.

The halo is unusual and implies a high level of dynamic activity which is likely due to gravitational stirring by the massive planets.[41] The Spitzer team says that collisions are likely occurring among bodies similar to those in the Kuiper Belt and that the three large planets may not yet have settled into their final, stable orbits.[42]

In the photo, the bright, yellow-white portions of the dust cloud come from the outer cold disk. The huge extended dust halo, seen in orange-red, has a diameter of ≈ 2,000 AU. The diameter of Pluto's orbit (≈ 80 AU) is shown for reference as a dot in the centre.[43]

This disk is so thick that it threatens the young system's stability.[44]

The disk was first resolved with ALMA in 2016[45] and was later imaged again in 2018. These later observations were more detailed and were studied by a team of astronomers. The disk has according to this team a smooth inner edge and a smooth outer edge. These also observed a possible inner dust belt.[24] This inner belt was confirmed with MIRI observations, which measured a radius of 15 au of the inner disk.[23]

Vortex Coronagraph: Testbed for high-contrast imaging technology

Up until the year 2010, telescopes could only directly image exoplanets under exceptional circumstances. Specifically, it is easier to obtain images when the planet is especially large (considerably larger than Jupiter), widely separated from its parent star, and hot so that it emits intense infrared radiation. However, in 2010 a team from NASAs Jet Propulsion Laboratory demonstrated that a vortex coronagraph could enable small telescopes to directly image planets.[46] They did this by imaging the previously imaged HR 8799 planets using just a 1.5 m portion of the Hale Telescope.

NICMOS images

In 2009, an old NICMOS image was processed to show a predicted exoplanet around HR 8799.[47] In 2011, three further exoplanets were rendered viewable in a NICMOS image taken in 1998, using advanced data processing.[47] The image allows the planets' orbits to be better characterised, since they take many decades to orbit their host star.[47]

Search for radio emissions

Starting in 2010, astronomers searched for radio emissions from the exoplanets orbiting HR 8799 using the radio telescope at Arecibo Observatory. Despite the large masses, warm temperatures, and brown dwarf-like luminosities, they failed to detect any emissions at 5 GHz down to a flux density detection threshold of 1.0 mJy.[48]

See also

- List of exoplanets

- Direct imaging of extrasolar planets

- HD 163296

- Circumplanetary disc

- HD 100546

- Exoplanet

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Vallenari, A. et al. (2022). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940 Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "HR 8799". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=HR+8799.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Gray, Richard O.; Kaye, Anthony B. (December 1999). "HR 8799: A link between γ Doradus variables and λ Bootis stars". The Astronomical Journal 118 (6): 2993–2996. doi:10.1086/301134. Bibcode: 1999AJ....118.2993G.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kaye, Anthony B.; Handler, Gerald; Krisciunas, Kevin; Poretti, Ennio; Zerbi, Filippo M. (July 1999). "Gamma Doradus stars: Defining a new class of pulsating variables". The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 111 (761): 840–844. doi:10.1086/316399. Bibcode: 1999PASP..111..840K.

- ↑ Hoffleit, Dorrit; Warren, Wayne H. Jr., eds (June 1991). "HR 8799". The Bright Star Catalogue (5th, revised ed.). Strasbourg, FR: Université de Strasbourg / CNRS. V/50. http://webviz.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/VizieR-5?-out.add=.&-source=V/50/catalog&recno=8799. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ↑ Sepulveda, Aldo G.; Bowler, Brendan P. (2022). "Dynamical Mass of the Exoplanet Host Star HR 8799". The Astronomical Journal 163 (2): 52. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac3bb5. Bibcode: 2022AJ....163...52S.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Baines, Ellyn K.; White, Russel J.; Huber, Daniel; Jones, Jeremy; Boyajian, Tabetha; McAlister, Harold A.; ten Brummelaar, Theo A.; Turner, Nils H. et al. (2012-11-21). "The CHARA Array Angular Diameter of HR 8799 Favors Planetary Masses for Its Imaged Companions". The Astrophysical Journal 761 (1): 57. doi:10.1088/0004-637x/761/1/57. ISSN 0004-637X. Bibcode: 2012ApJ...761...57B.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Wang, Ji; Wang, Jason J.; Ma, Bo; Chilcote, Jeffrey; Ertel, Steve; Guyon, Olivier et al. (2020). "On the chemical abundance of HR 8799 and the planet c". The Astronomical Journal 160 (3): 150. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ababa7. Bibcode: 2020AJ....160..150W.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Brandt, G. Mirek; Brandt, Timothy D.; Dupuy, Trent J.; Michalik, Daniel; Marleau, Gabriel-Dominique (2021-07-01). "The First Dynamical Mass Measurement in the HR 8799 System". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 915 (1): L16. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac0540. ISSN 2041-8205. Bibcode: 2021ApJ...915L..16B.

- ↑ Sódor, Á.; Chené, A. N.; De Cat, P.; Bognár, Zs.; Wright, D. J.; Marois, C.; Walker, G. A. H.; Matthews, J. M. et al. (August 2014). "MOST light-curve analysis of the γ Doradus pulsator HR 8799, showing resonances and amplitude variations". Astronomy and Astrophysics 568: A106. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201423976. Bibcode: 2014A&A...568A.106S.

- ↑ Moya, A.; Amado, P.J.; Barrado, D.; García Hernández, A.; Aberasturi, M.; Montesinos, B. et al. (June 2010). "Age determination of the HR 8799 planetary system using astero-seismology". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters 405 (1): L81–L85. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2010.00863.x. Bibcode: 2010MNRAS.405L..81M.

- ↑ Zuckerman, B.; Rhee, Joseph H.; Song, Inseok; Bessell, M.S. (May 2011). "The Tucana / Horologium, Columba, AB Doradus, and Argus associations: New members and dusty debris disks". The Astrophysical Journal 732 (2): 61. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/732/2/61. Bibcode: 2011ApJ...732...61Z.

- ↑ Kozo, Sadakane (2006). "λ Bootis-like abundances in the Vega-like, γ Doradus type-pulsator HD 218396". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 58 (6): 1023–1032. doi:10.1093/pasj/58.6.1023. Bibcode: 2006PASJ...58.1023S.

- ↑ Paunzen, E.; Weiss, W.W.; Kuschnig, R.; Handler, G.; Strassmeier, K.G.; North, P.; Solano, E.; Gelbmann, M. et al. (1998). "Pulsation in λ Bootis stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics 335: 533–538. Bibcode: 1998A&A...335..533P.

- ↑ Wright, D.J.; Chené, A.-N.; de Cat, P.; Marois, C.; Mathias, P.; Macintosh, B. et al. (February 2011). "Determination of the inclination of the multi-planet hosting star HR 8799 using astero-seismology". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 728 (1): L20. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/728/1/L20. Bibcode: 2011ApJ...728L..20W.

- ↑ Robrade, J.; Schmitt, J.H.M.M. (June 2010). "X-ray emission from the remarkable A‑type star HR 8799". Astronomy and Astrophysics 516: A38. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014027. Bibcode: 2010A&A...516A..38R.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 Marois, Christian; Zuckerman, B.; Konopacky, Quinn M.; Macintosh, Bruce; Barman, Travis (December 2010). "Images of a fourth planet orbiting HR 8799". Nature 468 (7327): 1080–1083. doi:10.1038/nature09684. PMID 21150902. Bibcode: 2010Natur.468.1080M.

- ↑ Schneider, J.. "Notes for star HR 8799". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. http://exoplanet.eu/star.php?st=HR+8799. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ↑ Lacour, S.; Nowak, M.; Wang, J.; Pfuhl, O.; Eisenhauer, F.; Abuter, R. et al. (March 2019). "First direct detection of an exoplanet by optical interferometry. Astrometry and K‑band spectroscopy of HR 8799 e". Astronomy and Astrophysics 623: L11. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935253. ISSN 0004-6361. Bibcode: 2019A&A...623L..11G.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Gozdziewski, Krzysztof; Migaszewski, Cezary (2020). "An exact, generalised Laplace resonance in the HR 8799 planetary system". The Astrophysical Journal 902 (2): L40. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abb881. Bibcode: 2020ApJ...902L..40G.

- ↑ Nasedkin, E.; Mollière, P.; Lacour, S.; Nowak, M.; Kreidberg, L.; Stolker, T.; Wang, J. J.; Balmer, W. O. et al. (July 2024). "Four-of-a-kind? Comprehensive atmospheric characterisation of the HR 8799 planets with VLTI/GRAVITY". Astronomy & Astrophysics 687: A298. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202449328. ISSN 0004-6361. Bibcode: 2024A&A...687A.298N. https://www.aanda.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202449328.

- ↑ Thompson, William; Marois, Christian; Do ó, Clarissa R.; Konopacky, Quinn; Ruffio, Jean-Baptiste; Wang, Jason; Skemer, Andy J.; De Rosa, Robert J. et al. (2023). "Deep Orbital Search for Additional Planets in the HR 8799 System". The Astronomical Journal 165 (1): 29. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aca1af. Bibcode: 2023AJ....165...29T.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Boccaletti, Anthony; Mâlin, Mathilde; Baudoz, Pierre; Tremblin, Pascal; Perrot, Clément; Rouan, Daniel; Lagage, Pierre-Olivier; Whiteford, Niall et al. (2024-06-01). "Imaging detection of the inner dust belt and the four exoplanets in the HR 8799 system with JWST's MIRI coronagraph". Astronomy and Astrophysics 686: A33. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202347912. ISSN 0004-6361. Bibcode: 2024A&A...686A..33B.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Faramaz, Virginie; Marino, Sebastian; Booth, Mark; Matrà, Luca; Mamajek, Eric E.; Bryden, Geoffrey et al. (2021). "A Detailed Characterization of HR 8799's Debris Disk with ALMA in Band 7". The Astronomical Journal 161 (6): 271. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abf4e0. Bibcode: 2021AJ....161..271F.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Marois, Christian; Macintosh, Bruce; Barman, Travis; Zuckerman, B.; Song, Inseok; Patience, Jennifer; Lafrenière, David; Doyon, René (November 2008). "Direct imaging of multiple planets orbiting the star HR 8799". Science 322 (5906): 1348–1352. doi:10.1126/science.1166585. PMID 19008415. Bibcode: 2008Sci...322.1348M.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Gemini releases historic discovery image of planetary first family" (Press release). Gemini Observatory. 13 November 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ↑ "Astronomers capture first images of newly-discovered solar system" (Press release). W. M. Keck Observatory. 13 November 2008. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- ↑ Achenbach, Joel (13 November 2008). "Scientists publish first direct images of extrasolar planets". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/11/13/AR2008111302267.html.

- ↑ Villard, Ray; Lafreniere, David (1 April 2009). "Hubble finds hidden exoplanet in archival data". Hubble Space Telescope Science Institute. HubbleSite (Press release). NASA. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Currie, Thayne (March 2011). "A combined Subaru/VLT/MMT 1–5 micron study of planets orbiting HR 8799: Implications for atmospheric properties, masses, and formation". The Astrophysical Journal 729 (2): 128. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/729/2/128. Bibcode: 2011ApJ...729..128C.

- ↑ Skemer, Andrew (July 2012). "First light LBT AO images of HR 8799 bcde at 1.6 and 3.3 µm: New discrepancies between young planets and old brown dwarfs". The Astrophysical Journal 753 (1): 14. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/753/1/14. Bibcode: 2012ApJ...753...14S.

- ↑ Staff, Astronomy (2008-11-13). "Astronomers capture first images of newly discovered solar system | Astronomy.com" (in en-US). https://www.astronomy.com/science/astronomers-capture-first-images-of-newly-discovered-solar-system/.

- ↑ "Definition of a "Planet"". The International Astronomical Union (IAU). 28 February 2003. http://www.dtm.ciw.edu/boss/definition.html.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Oppenheimer, B.R.; Baranec, C.; Beichman, C.; Brenner, D.; Burruss, R.; Cady, E. et al. (2013). "Reconnaissance of the HR 8799 exosolar system I: Near-IR spectroscopy". Astrophysical Journal 768 (1): 24. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/768/1/24. Bibcode: 2013ApJ...768...24O.

- ↑ Beichman, Charles A.; Balmer, William; Bryden, Geoffrey; Hodapp, Klaus Werner; Leisenring, Jarron; Pueyo, Laurent; Ygouf, Marie (2023-06-01). "follow-up Observations of NIRCAm Sources in the planetary system HR8799". JWST Proposal. Cycle 3: 4535. Bibcode: 2023jwst.prop.4535B. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2023jwst.prop.4535B/abstract.

- ↑ Bowler, Brendan P. (2010). "Near-infrared Spectroscopy of the Extrasolar Planet HR 8799 b". Astrophysical Journal 723 (1): 850. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/850. Bibcode: 2010ApJ...723..850B.

- ↑ Barman, Travis S.; Macintosh, Bruce (2011). "Clouds and chemistry in the atmosphere of extrasolar planet HR 8799 b". Astrophysical Journal 733 (65): 65. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/733/1/65. Bibcode: 2011ApJ...733...65B.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Konopacky, Quinn M.; Barman, Travis S. (2013). "Detection of carbon monoxide and water absorption lines in an exoplanet atmosphere". Science (AAAS) 339 (6126): 1398–1401. doi:10.1126/science.1232003. PMID 23493423. Bibcode: 2013Sci...339.1398K.

- ↑ "Exoplanet stepping stones" (Press release). W. M. Keck Observatory. 20 November 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ↑ Wang, Ji; Mawet, Dimitri; Fortney, Jonathan J.; Hood, Callie; Morley, Caroline V.; Benneke, Björn (December 2018). "Detecting water in the atmosphere of HR 8799 c with L-band high-dispersion spectroscopy aided by adaptive optics". The Astronomical Journal 156 (6): 272. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aae47b. Bibcode: 2018AJ....156..272W.

- ↑ Su, K.Y.L.; Rieke, G.H.; Stapelfeldt, K.R.; Malhotra, R.; Bryden, G.; Smith, P.S.; Misselt, K.A.; Moro-Martin, A. et al. (2009). "The debris disk around HR 8799". The Astrophysical Journal 705 (1): 314–327. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/705/1/314. Bibcode: 2009ApJ...705..314S.

- ↑ "Unsettled youth: Spitzer observes a chaotic planetary system". Spitzer Space Telescope (Press release). NASA / Caltech. 4 November 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- ↑ "A picture of unsettled planetary youth". Spitzer Space Telescope (Press release). NASA / Caltech. 4 November 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- ↑ Moore, Alexander J.; Quillen, Alice C. (2013). "Effects of a planetesimal debris disk on stability scenarios for the extrasolar planetary system HR 8799". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 430 (1): 320–329. doi:10.1093/mnras/sts625. Bibcode: 2013MNRAS.430..320M.

- ↑ "Cometary Belt around Distant Multi-Planet System Hints at Hidden or Wandering Planets | ALMA" (in en-US). 2016-05-17. https://www.almaobservatory.org/en/press-releases/cometary-belt-around-distant-multi-planet-system-hints-at-hidden-or-wandering-planets/.

- ↑ "New method could image Earth-like planets". 14 April 2010. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/36528711.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "Astronomers find elusive planets in decade-old Hubble data". NASA.gov (Press release). Hubble mission. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 2 September 2014.

- ↑ Route, Matthew; Wolszczan, Alexander (August 2013). "The 5 GHz Arecibo search for radio flares from ultracool dwarfs". The Astrophysical Journal 773 (1): 18. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/773/1/18. Bibcode: 2013ApJ...773...18R.

External links

Coordinates: ![]() 23h 07m 28.7150s, +21° 08′ 03.302″

23h 07m 28.7150s, +21° 08′ 03.302″

|