Biology:Crenarchaeota

| Crenarchaeota | |

|---|---|

| |

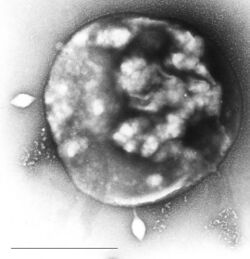

| Archaea Sulfolobus infected with specific virus STSV-1. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Superphylum: | |

| Phylum: | "Crenarchaeota" Garrity & Holt 2002

|

| Class | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Crenarchaeota (also known as Crenarchaea or eocytes) are archaea that have been classified as a phylum of the Archaea domain.[1][2][3] Initially, the Crenarchaeota were thought to be sulfur-dependent extremophiles but recent studies have identified characteristic Crenarchaeota environmental rRNA indicating the organisms may be the most abundant archaea in the marine environment.[4] Originally, they were separated from the other archaea based on rRNA sequences; other physiological features, such as lack of histones, have supported this division, although some crenarchaea were found to have histones.[5] Until recently all cultured Crenarchaea had been thermophilic or hyperthermophilic organisms, some of which have the ability to grow at up to 113 °C.[6] These organisms stain Gram negative and are morphologically diverse, having rod, cocci, filamentous and oddly-shaped cells.[7]

Sulfolobus

One of the best characterized members of the Crenarcheota is Sulfolobus solfataricus. This organism was originally isolated from geothermally heated sulfuric springs in Italy, and grows at 80 °C and pH of 2–4.[8] Since its initial characterization by Wolfram Zillig, a pioneer in thermophile and archaean research, similar species in the same genus have been found around the world. Unlike the vast majority of cultured thermophiles, Sulfolobus grows aerobically and chemoorganotrophically (gaining its energy from organic sources such as sugars). These factors allow a much easier growth under laboratory conditions than anaerobic organisms and have led to Sulfolobus becoming a model organism for the study of hyperthermophiles and a large group of diverse viruses that replicate within them.

Marine species

Beginning in 1992, data were published that reported sequences of genes belonging to the Crenarchaea in marine environments.[9],[10] Since then, analysis of the abundant lipids from the membranes of Crenarchaea taken from the open ocean have been used to determine the concentration of these “low temperature Crenarchaea” (See TEX-86). Based on these measurements of their signature lipids, Crenarchaea are thought to be very abundant and one of the main contributors to the fixation of carbon .[citation needed] DNA sequences from Crenarchaea have also been found in soil and freshwater environments, suggesting that this phylum is ubiquitous to most environments.[11]

In 2005, evidence of the first cultured “low temperature Crenarchaea” was published. Named Nitrosopumilus maritimus, it is an ammonia-oxidizing organism isolated from a marine aquarium tank and grown at 28 °C.[12]

Eocyte hypothesis

The eocyte hypothesis proposed in the 1980s by James Lake suggests that eukaryotes emerged within the prokaryotic eocytes.[14]

One possible piece of evidence supporting a close relationship between Crenarchaea and eukaryotes is the presence of a homolog of the RNA polymerase subunit Rbp-8 in Crenarchea but not in Euryarchaea[15]

See also

References

- ↑ See the NCBI webpage on Crenarchaeota

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan. 2010. Archaea. eds. E.Monosson & C.Cleveland, Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment, Washington DC.

- ↑ Data extracted from the "NCBI taxonomy resources". National Center for Biotechnology Information. http://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/pub/taxonomy/.

- ↑ Madigan M, ed (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-144329-7.

- ↑ "Histones in Crenarchaea". Journal of Bacteriology 187 (15): 5482–5485. 2005. doi:10.1128/JB.187.15.5482-5485.2005. PMID 16030242.

- ↑ "Pyrolobus fumarii, gen. and sp. nov., represents a novel group of archaea, extending the upper temperature limit for life to 113 °C". Extremophiles 1 (1): 14–21. 1997. doi:10.1007/s007920050010. PMID 9680332.

- ↑ Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology Volume 1: The Archaea and the Deeply Branching and Phototrophic Bacteria (2nd ed.). Springer. 2001. ISBN 978-0-387-98771-2. https://archive.org/details/bergeysmanualofs00boon.

- ↑ "The Sulfolobus-"Caldariellard" group: Taxonomy on the basis of the structure of DNA-dependent RNA polymerases". Arch. Microbiol. 125 (3): 259–269. 1980. doi:10.1007/BF00446886.

- ↑ "Novel major archaebacterial group from marine plankton". Nature 356 (6365): 148–9. 1992. doi:10.1038/356148a0. PMID 1545865. Bibcode: 1992Natur.356..148F.

- ↑ DeLong EF (1992). "Archaea in coastal marine environments". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89 (12): 5685–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.12.5685. PMID 1608980. Bibcode: 1992PNAS...89.5685D.

- ↑ "Perspectives on archaeal diversity, thermophily and monophyly from environmental rRNA sequences". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 (17): 9188–93. 1996. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.17.9188. PMID 8799176. Bibcode: 1996PNAS...93.9188B.

- ↑ "Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon". Nature 437 (7058): 543–6. 2005. doi:10.1038/nature03911. PMID 16177789. Bibcode: 2005Natur.437..543K.

- ↑ Cox, C. J.; Foster, P. G.; Hirt, R. P.; Harris, S. R.; Embley, T. M. (2008). "The archaebacterial origin of eukaryotes". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105 (51): 20356–61. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810647105. PMID 19073919. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..10520356C.

- ↑ (UCLA) The origin of the nucleus and the tree of life

- ↑ Kwapisz, M; Beckouët, F; Thuriaux, P (2008). "Early evolution of eukaryotic DNA-dependent RNA polymerases". Trends Genet. 24 (5): 211–5. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2008.02.002. PMID 18384908.

Further reading

Scientific journals

- Cavalier-Smith, T (2002). "The neomuran origin of archaebacteria, the negibacterial root of the universal tree and bacterial megaclassification". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52 (Pt 1): 7–76. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-1-7. PMID 11837318.

- Stackebrandt, E; Frederiksen W; Garrity GM; Grimont PA; Kampfer P; Maiden MC; Nesme X; Rossello-Mora R et al. (2002). "Report of the ad hoc committee for the re-evaluation of the species definition in bacteriology". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52 (Pt 3): 1043–1047. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02360-0. PMID 12054223.

- Gurtler, V; Mayall BC (2001). "Genomic approaches to typing, taxonomy and evolution of bacterial isolates". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51 (Pt 1): 3–16. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-1-3. PMID 11211268.

- Dalevi, D; Hugenholtz P; Blackall LL (2001). "A multiple-outgroup approach to resolving division-level phylogenetic relationships using 16S rDNA data". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51 (Pt 2): 385–391. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-2-385. PMID 11321083.

- Keswani, J; Whitman WB (2001). "Relationship of 16S rRNA sequence similarity to DNA hybridization in prokaryotes". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51 (Pt 2): 667–678. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-2-667. PMID 11321113.

- Young, JM (2001). "Implications of alternative classifications and horizontal gene transfer for bacterial taxonomy". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51 (Pt 3): 945–953. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-3-945. PMID 11411719.

- Christensen, H; Bisgaard M; Frederiksen W; Mutters R; Kuhnert P; Olsen JE (2001). "Is characterization of a single isolate sufficient for valid publication of a new genus or species? Proposal to modify recommendation 30b of the Bacteriological Code (1990 Revision)". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51 (Pt 6): 2221–2225. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-6-2221. PMID 11760965.

- Christensen, H; Angen O; Mutters R; Olsen JE; Bisgaard M (2000). "DNA-DNA hybridization determined in micro-wells using covalent attachment of DNA". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50 (3): 1095–1102. doi:10.1099/00207713-50-3-1095. PMID 10843050.

- Xu, HX; Kawamura Y; Li N; Zhao L; Li TM; Li ZY; Shu S; Ezaki T (2000). "A rapid method for determining the G+C content of bacterial chromosomes by monitoring fluorescence intensity during DNA denaturation in a capillary tube". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50 (4): 1463–1469. doi:10.1099/00207713-50-4-1463. PMID 10939651.

- Young, JM (2000). "Suggestions for avoiding on-going confusion from the Bacteriological Code". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50 (4): 1687–1689. doi:10.1099/00207713-50-4-1687. PMID 10939677.

- Hansmann, S; Martin W (2000). "Phylogeny of 33 ribosomal and six other proteins encoded in an ancient gene cluster that is conserved across prokaryotic genomes: influence of excluding poorly alignable sites from analysis". Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50 (4): 1655–1663. doi:10.1099/00207713-50-4-1655. PMID 10939673.

- Tindall, BJ (1999). "Proposal to change the Rule governing the designation of type strains deposited under culture collection numbers allocated for patent purposes". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49 (3): 1317–1319. doi:10.1099/00207713-49-3-1317. PMID 10490293.

- Tindall, BJ (1999). "Proposal to change Rule 18a, Rule 18f and Rule 30 to limit the retroactive consequences of changes accepted by the ICSB". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49 (3): 1321–1322. doi:10.1099/00207713-49-3-1321. PMID 10425797.

- Tindall, BJ (1999). "Misunderstanding the Bacteriological Code". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49 (3): 1313–1316. doi:10.1099/00207713-49-3-1313. PMID 10425796.

- Tindall, BJ (1999). "Proposals to update and make changes to the Bacteriological Code". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49 (3): 1309–1312. doi:10.1099/00207713-49-3-1309. PMID 10425795.

- Burggraf, S; Huber H; Stetter KO (1997). "Reclassification of the crenarchael orders and families in accordance with 16S rRNA sequence data". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47 (3): 657–660. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-3-657. PMID 9226896.

- Palys, T; Nakamura LK; Cohan FM (1997). "Discovery and classification of ecological diversity in the bacterial world: the role of DNA sequence data". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47 (4): 1145–1156. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-4-1145. PMID 9336922.

- Euzeby, JP (1997). "List of Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature: a folder available on the Internet". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47 (2): 590–592. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-2-590. PMID 9103655.

- Clayton, RA; Sutton G; Hinkle PS Jr; Bult C; Fields C (1995). "Intraspecific variation in small-subunit rRNA sequences in GenBank: why single sequences may not adequately represent prokaryotic taxa". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45 (3): 595–599. doi:10.1099/00207713-45-3-595. PMID 8590690.

- Murray, RG; Schleifer KH (1994). "Taxonomic notes: a proposal for recording the properties of putative taxa of procaryotes". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44 (1): 174–176. doi:10.1099/00207713-44-1-174. PMID 8123559.

- Winker, S; Woese CR (1991). "A definition of the domains Archaea, Bacteria and Eucarya in terms of small subunit ribosomal RNA characteristics". Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 14 (4): 305–310. doi:10.1016/s0723-2020(11)80303-6. PMID 11540071.

- Woese, CR; Kandler O; Wheelis ML (1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87 (12): 4576–4579. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMID 2112744. Bibcode: 1990PNAS...87.4576W.

- Achenbach-Richter, L; Woese CR (1988). "The ribosomal gene spacer region in archaebacteria". Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 10 (3): 211–214. doi:10.1016/s0723-2020(88)80002-x. PMID 11542149.

- McGill, TJ; Jurka J; Sobieski JM; Pickett MH; Woese CR; Fox GE (1986). "Characteristic archaebacterial 16S rRNA oligonucleotides". Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 7 (2–3): 194–197. doi:10.1016/S0723-2020(86)80005-4. PMID 11542064.

- Woese, CR; Gupta R; Hahn CM; Zillig W; Tu J (1984). "The phylogenetic relationships of three sulfur dependent archaebacteria". Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 5: 97–105. doi:10.1016/S0723-2020(84)80054-5. PMID 11541975.

- Woese, CR; Olsen GJ (1984). "The phylogenetic relationships of three sulfur dependent archaebacteria". Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 5: 97–105. doi:10.1016/S0723-2020(84)80054-5. PMID 11541975.

- Woese, CR; Fox GE (1977). "Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74 (11): 5088–5090. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.11.5088. PMID 270744. Bibcode: 1977PNAS...74.5088W.

Scientific books

- "Phylum AI. Crenarchaeota phy. nov.". Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology Volume 1: The Archaea and the deeply branching and phototrophic Bacteria (2nd ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. 2001. pp. 169. ISBN 978-0-387-98771-2. https://archive.org/details/bergeysmanualofs00boon.

Scientific databases

- PubMed references for Crenarchaeota

- PubMed Central references for Crenarchaeota

- Google Scholar references for Crenarchaeota

External links

- NCBI taxonomy page for Crenarchaeota

- Search Tree of Life taxonomy pages for Crenarchaeota

- Search Species2000 page for Crenarchaeota

- MicrobeWiki page for Crenarchaeota

- LPSN page for Crenarchaeota

- Crenarchaeota from the University of Wisconsin Virtual Microbiology site.

- Comparative Analysis of Crenarchaeal Genomes (at DOE's IMG system)

Wikidata ☰ Q499078 entry

xclvkjesodkd0riyjtokgpfdoi-s-bj9tjhitebjtr3iog-kwg-it9jhti39fjo3ir=hj3kflrpj0yu3]i09ogkij