Biology:Histone

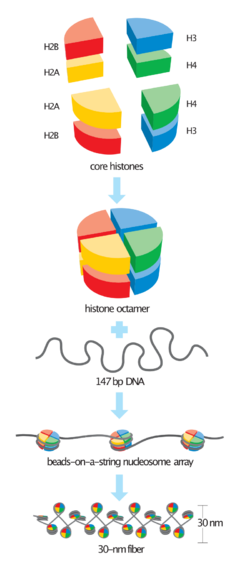

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes.[1][2] Nucleosomes in turn are wrapped into 30-nanometer fibers that form tightly packed chromatin. Histones prevent DNA from becoming tangled and protect it from DNA damage. In addition, histones play important roles in gene regulation and DNA replication. Without histones, unwound DNA in chromosomes would be very long. For example, each human cell has about 1.8 meters of DNA if completely stretched out; however, when wound about histones, this length is reduced to about 9 micrometers (0.009 mm) of 30 nm diameter chromatin fibers.[3]

There are five families of histones, which are designated H1/H5 (linker histones), H2, H3, and H4 (core histones). The nucleosome core is formed of two H2A-H2B dimers and a H3-H4 tetramer. The tight wrapping of DNA around histones, is to a large degree, a result of electrostatic attraction between the positively charged histones and negatively charged phosphate backbone of DNA.

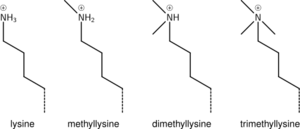

Histones may be chemically modified through the action of enzymes to regulate gene transcription. The most common modifications are the methylation of arginine or lysine residues or the acetylation of lysine. Methylation can affect how other proteins such as transcription factors interact with the nucleosomes. Lysine acetylation eliminates a positive charge on lysine thereby weakening the electrostatic attraction between histone and DNA, resulting in partial unwinding of the DNA, making it more accessible for gene expression.

Classes and variants

Five major families of histone proteins exist: H1/H5, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4.[2][4][5][6] Histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4 are known as the core or nucleosomal histones, while histones H1/H5 are known as the linker histones.

The core histones all exist as dimers, which are similar in that they all possess the histone fold domain: three alpha helices linked by two loops. It is this helical structure that allows for interaction between distinct dimers, particularly in a head-tail fashion (also called the handshake motif).[7] The resulting four distinct dimers then come together to form one octameric nucleosome core, approximately 63 Angstroms in diameter (a solenoid (DNA)-like particle). Around 146 base pairs (bp) of DNA wrap around this core particle 1.65 times in a left-handed super-helical turn to give a particle of around 100 Angstroms across.[8] The linker histone H1 binds the nucleosome at the entry and exit sites of the DNA, thus locking the DNA into place[9] and allowing the formation of higher order structure. The most basic such formation is the 10 nm fiber or beads on a string conformation. This involves the wrapping of DNA around nucleosomes with approximately 50 base pairs of DNA separating each pair of nucleosomes (also referred to as linker DNA). Higher-order structures include the 30 nm fiber (forming an irregular zigzag) and 100 nm fiber, these being the structures found in normal cells. During mitosis and meiosis, the condensed chromosomes are assembled through interactions between nucleosomes and other regulatory proteins.

Histones are subdivided into canonical replication-dependent histones, whose genes are expressed during the S-phase of the cell cycle and replication-independent histone variants, expressed during the whole cell cycle. In mammals, genes encoding canonical histones are typically clustered along chromosomes in 4 different highly-conserved loci, lack introns and use a stem loop structure at the 3' end instead of a polyA tail. Genes encoding histone variants are usually not clustered, have introns and their mRNAs are regulated with polyA tails.[10] Complex multicellular organisms typically have a higher number of histone variants providing a variety of different functions. Functionally, histone variants contribute to transcriptional control, epigenetic memory, and DNA repair, serving specialized functions beyond nucleosome packaging which plays distinct roles in chromatin dynamics. For example, H2A.Z is enriched at regulatory elements and promoters of actively transcribed genes, where it modulates nucleosome stability and transcription factor binding. In contrast, H3.3, a replacement variant of Histone H3, is associated with active transcription and is preferentially deposited at enhancer elements and transcribed gene bodies. Another critical variant, CENPA, replaces H3 in centromeric nucleosomes, providing a structural foundation essential for chromosome segregation.[11]

Variants also play essential roles in DNA repair. Variants such as H2A.X are phosphorylated at sites of DNA damage, marking regions for recruitment of repair proteins. This modification, commonly referred to as γH2A.X, serves as a key signal in the cellular response to double-strand breaks, facilitating efficient DNA repair processes. Defects in histone variant regulation have been linked to genome instability, a hallmark of many cancers and age-related diseases.[12]

Recent data are accumulating about the roles of diverse histone variants highlighting the functional links between variants and the delicate regulation of organism development.[13] Histone variants proteins from different organisms, their classification and variant specific features can be found in "HistoneDB 2.0 - Variants" database.[14][15] Several pseudogenes have also been discovered and identified in very close sequences of their respective functional ortholog genes.[16][17]

The following is a list of human histone proteins, genes and pseudogenes:[10]

| Super family | Family | Replication-dependent genes | Replication-independent genes | Pseudogenes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linker | H1 | H1-1, H1-2, H1-3, H1-4, H1-5, H1-6 | H1-0, H1-7, H1-8, H1-10 | H1-9P, H1-12P |

| Core | H2A | H2AC1, H2AC4, H2AC6, H2AC7, H2AC8, H2AC11, H2AC12, H2AC13, H2AC14, H2AC15, H2AC16, H2AC17, H2AC18, H2AC19, H2AC20, H2AC21, H2AC25 | H2AZ1, H2AZ2, MACROH2A1, MACROH2A2, H2AX, H2AJ, H2AB1, H2AB2, H2AB3, H2AP, H2AL1Q, H2AL3 | H2AC2P, H2AC3P, H2AC5P, H2AC9P, H2AC10P, H2AQ1P, H2AL1MP |

| H2B | H2BC1, H2BC3, H2BC4, H2BC5, H2BC6, H2BC7, H2BC8, H2BC9, H2BC10, H2BC11, H2BC12, H2BC13, H2BC14, H2BC15, H2BC17, H2BC18, H2BC21, H2BC26, H2BC12L | H2BK1, H2BW1, H2BW2, H2BW3P, H2BN1 | H2BC2P, H2BC16P, H2BC19P, H2BC20P, H2BC27P, H2BL1P, H2BW3P, H2BW4P | |

| H3 | H3C1, H3C2, H3C3, H3C4, H3C6, H3C7, H3C8, H3C10, H3C11, H3C12, H3C13, H3C14, H3C15, H3-4 | H3-3A, H3-3B, H3-5, H3-7, H3Y1, H3Y2, CENPA | H3C5P, H3C9P, H3P16, H3P44 | |

| H4 | H4C1, H4C2, H4C3, H4C4, H4C5, H4C6, H4C7, H4C8, H4C9, H4C11, H4C12, H4C13, H4C14, H4C15 | H4C16 | H4C10P |

Structure

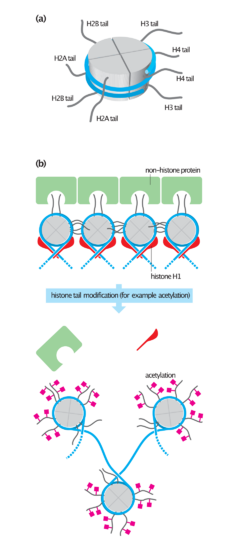

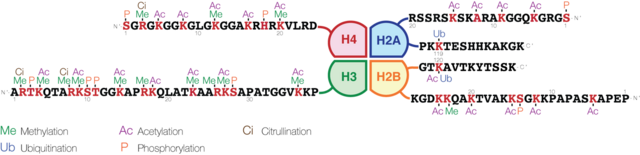

The nucleosome core is formed of two H2A-H2B dimers and a H3-H4 tetramer, forming two nearly symmetrical halves by tertiary structure (C2 symmetry; one macromolecule is the mirror image of the other).[8] The H2A-H2B dimers and H3-H4 tetramer also show pseudodyad symmetry. The 4 'core' histones (H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) are relatively similar in structure and are highly conserved through evolution, all featuring a 'helix turn helix turn helix' motif (DNA-binding protein motif that recognize specific DNA sequence). They also share the feature of long 'tails' on one end of the amino acid structure - this being the location of post-translational modification (see below).[18]

Archaeal histone only contains a H3-H4 like dimeric structure made out of a single type of unit. Such dimeric structures can stack into a tall superhelix ("hypernucleosome") onto which DNA coils in a manner similar to nucleosome spools.[19] Only some archaeal histones have tails.[20]

The distance between the spools around which eukaryotic cells wind their DNA has been determined to range from 59 to 70 Å.[21]

In all, histones make five types of interactions with DNA:

- Salt bridges and hydrogen bonds between side chains of basic amino acids (especially lysine and arginine) and phosphate oxygens on DNA

- Helix-dipoles form alpha-helixes in H2B, H3, and H4 cause a net positive charge to accumulate at the point of interaction with negatively charged phosphate groups on DNA

- Hydrogen bonds between the DNA backbone and the amide group on the main chain of histone proteins

- Nonpolar interactions between the histone and deoxyribose sugars on DNA

- Non-specific minor groove insertions of the H3 and H2B N-terminal tails into two minor grooves each on the DNA molecule

The highly basic nature of histones, aside from facilitating DNA-histone interactions, contributes to their water solubility.

Histones are subject to post translational modification by enzymes primarily on their N-terminal tails, but also in their globular domains.[22][23] Such modifications include methylation, citrullination, acetylation, phosphorylation, SUMOylation, ubiquitination, and ADP-ribosylation. This affects their function of gene regulation.

In general, genes that are active have less bound histone, while inactive genes are highly associated with histones during interphase.[24] It also appears that the structure of histones has been evolutionarily conserved, as any deleterious mutations would be severely maladaptive. All histones have a highly positively charged N-terminus with many lysine and arginine residues.

Evolution and species distribution

Core histones are found in the nuclei of eukaryotic cells and in most Archaeal phyla, but not in bacteria.[20] The unicellular algae known as dinoflagellates were previously thought to be the only eukaryotes that completely lack histones,[25] but later studies showed that their DNA still encodes histone genes.[26] Unlike the core histones, homologs of the lysine-rich linker histone (H1) proteins are found in bacteria, otherwise known as nucleoprotein HC1/HC2.[27]

It has been proposed that core histone proteins are evolutionarily related to the helical part of the extended AAA+ ATPase domain, the C-domain, and to the N-terminal substrate recognition domain of Clp/Hsp100 proteins. Despite the differences in their topology, these three folds share a homologous helix-strand-helix (HSH) motif.[18] It's also proposed that they may have evolved from ribosomal proteins (RPS6/RPS15), both being short and basic proteins.[28]

Archaeal histones may well resemble the evolutionary precursors to eukaryotic histones.[20] Histone proteins are among the most highly conserved proteins in eukaryotes, emphasizing their important role in the biology of the nucleus.[2]: 939 In contrast mature sperm cells largely use protamines to package their genomic DNA, most likely because this allows them to achieve an even higher packaging ratio.[29]

There are some variant forms in some of the major classes. They share amino acid sequence homology and core structural similarity to a specific class of major histones but also have their own feature that is distinct from the major histones. These minor histones usually carry out specific functions of the chromatin metabolism. For example, histone H3-like CENPA is associated with only the centromere region of the chromosome. Histone H2A variant H2A.Z is associated with the promoters of actively transcribed genes and also involved in the prevention of the spread of silent heterochromatin.[30] Furthermore, H2A.Z has roles in chromatin for genome stability.[31] Another H2A variant H2A.X is phosphorylated at S139 in regions around double-strand breaks and marks the region undergoing DNA repair.[32] Histone H3.3 is associated with the body of actively transcribed genes.[33]

Function

Compacting DNA strands

Histones act as spools around which DNA winds. This enables the compaction necessary to fit the large genomes of eukaryotes inside cell nuclei: the compacted molecule is 40,000 times shorter than an unpacked molecule.

Transcription

The effect of histones on transcription was established already in the late 1980s. Specifically, when histones are mutated or depleted a substantial activation of transcription occurs and is independent of other transcription factors (or suggesting that the latter displace histones).[34]

Chromatin regulation

Histones undergo posttranslational modifications that alter their interaction with DNA and nuclear proteins. The H3 and H4 histones have long tails protruding from the nucleosome, which can be covalently modified at several places. Modifications of the tail include methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, citrullination, and ADP-ribosylation. The core of the histones H2A and H2B can also be modified. Combinations of modifications, known as histone marks, are thought to constitute a code, the so-called "histone code".[35][36] Histone modifications act in diverse biological processes such as gene regulation, DNA repair, chromosome condensation (mitosis) and spermatogenesis (meiosis).[37]

The common nomenclature of histone modifications is:

- The name of the histone (e.g., H3)

- The single-letter amino acid abbreviation (e.g., K for Lysine) and the amino acid position in the protein

- The type of modification (Me: methyl, P: phosphate, Ac: acetyl, Ub: ubiquitin)

- The number of modifications (only Me is known to occur in more than one copy per residue. 1, 2 or 3 is mono-, di- or tri-methylation)

So H3K4me1 denotes the monomethylation of the 4th residue (a lysine) from the start (i.e., the N-terminal) of the H3 protein.

| Type of modification |

Histone | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4 | H3K9 | H3K14 | H3K27 | H3K79 | H3K36 | H4K20 | H2BK5 | H2BK20 | |

| mono-methylation | activation[38] | activation[39] | activation[39] | activation[39][40] | activation[39] | activation[39] | |||

| di-methylation | repression[41] | repression[41] | activation[40] | ||||||

| tri-methylation | activation[42] | repression[39] | repression[39] | activation,[40] repression[39] |

activation | repression[43] | |||

| acetylation | activation[44] | activation[42] | activation[42] | activation[45] | activation | ||||

Modification

A huge catalogue of histone modifications have been described, but a functional understanding of most is still lacking. Collectively, it is thought that histone modifications may underlie a histone code, whereby combinations of histone modifications have specific meanings. However, most functional data concerns individual prominent histone modifications that are biochemically amenable to detailed study.

Chemistry

Lysine methylation

The addition of one, two, or many methyl groups to lysine has little effect on the chemistry of the histone; methylation leaves the charge of the lysine intact and adds a minimal number of atoms so steric interactions are mostly unaffected. However, proteins containing Tudor, chromo or PHD domains, amongst others, can recognise lysine methylation with exquisite sensitivity and differentiate mono, di and tri-methyl lysine, to the extent that, for some lysines (e.g.: H4K20) mono, di and tri-methylation appear to have different meanings. Because of this, lysine methylation tends to be a very informative mark and dominates the known histone modification functions.

Glutamine serotonylation

Recently it has been shown, that the addition of a serotonin group to the position 5 glutamine of H3, happens in serotonergic cells such as neurons. This is part of the differentiation of the serotonergic cells. This post-translational modification happens in conjunction with the H3K4me3 modification. The serotonylation potentiates the binding of the general transcription factor TFIID to the TATA box.[46]

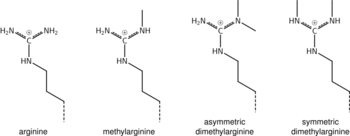

Arginine methylation

What was said above of the chemistry of lysine methylation also applies to arginine methylation, and some protein domains—e.g., Tudor domains—can be specific for methyl arginine instead of methyl lysine. Arginine is known to be mono- or di-methylated, and methylation can be symmetric or asymmetric, potentially with different meanings.

Arginine citrullination

Enzymes called peptidylarginine deiminases (PADs) hydrolyze the imine group of arginines and attach a keto group, so that there is one less positive charge on the amino acid residue. This process has been involved in the activation of gene expression by making the modified histones less tightly bound to DNA and thus making the chromatin more accessible.[47] PADs can also produce the opposite effect by removing or inhibiting mono-methylation of arginine residues on histones and thus antagonizing the positive effect arginine methylation has on transcriptional activity.[48]

Lysine acetylation

Addition of an acetyl group has a major chemical effect on lysine as it neutralises the positive charge. This reduces electrostatic attraction between the histone and the negatively charged DNA backbone, loosening the chromatin structure; highly acetylated histones form more accessible chromatin and tend to be associated with active transcription. Lysine acetylation appears to be less precise in meaning than methylation, in that histone acetyltransferases tend to act on more than one lysine; presumably this reflects the need to alter multiple lysines to have a significant effect on chromatin structure. The modification includes H3K27ac.

Serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphorylation

File:Amino acid phosphorylations.tif

Addition of a negatively charged phosphate group can lead to major changes in protein structure, leading to the well-characterised role of phosphorylation in controlling protein function. It is not clear what structural implications histone phosphorylation has, but histone phosphorylation has clear functions as a post-translational modification, and binding domains such as BRCT have been characterised.

Effects on transcription

Histone modifications are involved in control of transcription.

Actively transcribed genes

Two histone modifications are particularly associated with active transcription:

- Trimethylation of H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3)

- This trimethylation occurs at the promoter of active genes[49][50][51] and is performed by the COMPASS complex.[52][53][54] Despite the conservation of this complex and histone modification from yeast to mammals, it is not entirely clear what role this modification plays. However, it is an excellent mark of active promoters and the level of this histone modification at a gene's promoter is broadly correlated with transcriptional activity of the gene. The formation of this mark is tied to transcription in a rather convoluted manner: early in transcription of a gene, RNA polymerase II undergoes a switch from initiating' to 'elongating', marked by a change in the phosphorylation states of the RNA polymerase II C terminal domain (CTD). The same enzyme that phosphorylates the CTD also phosphorylates the Rad6 complex,[55][56] which in turn adds a ubiquitin mark to H2B K123 (K120 in mammals).[57] H2BK123Ub occurs throughout transcribed regions, but this mark is required for COMPASS to trimethylate H3K4 at promoters.[58][59]

- Trimethylation of H3 lysine 36 (H3K36me3)

- This trimethylation occurs in the body of active genes and is deposited by the methyltransferase Set2.[60] This protein associates with elongating RNA polymerase II, and H3K36Me3 is indicative of actively transcribed genes.[61] H3K36Me3 is recognised by the Rpd3 histone deacetylase complex, which removes acetyl modifications from surrounding histones, increasing chromatin compaction and repressing spurious transcription.[62][63][64] Increased chromatin compaction prevents transcription factors from accessing DNA, and reduces the likelihood of new transcription events being initiated within the body of the gene. This process therefore helps ensure that transcription is not interrupted.

Repressed genes

Three histone modifications are particularly associated with repressed genes:

- Trimethylation of H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3)

- This histone modification is deposited by the polycomb complex PRC2.[65] It is a clear marker of gene repression,[66] and is likely bound by other proteins to exert a repressive function. Another polycomb complex, PRC1, can bind H3K27me3[66] and adds the histone modification H2AK119Ub which aids chromatin compaction.[67][68] Based on this data it appears that PRC1 is recruited through the action of PRC2, however, recent studies show that PRC1 is recruited to the same sites in the absence of PRC2.[69][70]

- Di and tri-methylation of H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me2/3)

- H3K9me2/3 is a well-characterised marker for heterochromatin, and is therefore strongly associated with gene repression. The formation of heterochromatin has been best studied in the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, where it is initiated by recruitment of the RNA-induced transcriptional silencing (RITS) complex to double stranded RNAs produced from centromeric repeats.[71] RITS recruits the Clr4 histone methyltransferase which deposits H3K9me2/3.[72] This process is called histone methylation. H3K9Me2/3 serves as a binding site for the recruitment of Swi6 (heterochromatin protein 1 or HP1, another classic heterochromatin marker)[73][74] which in turn recruits further repressive activities including histone modifiers such as histone deacetylases and histone methyltransferases.[75]

- Trimethylation of H4 lysine 20 (H4K20me3)

- This modification is tightly associated with heterochromatin,[76][77] although its functional importance remains unclear. This mark is placed by the Suv4-20h methyltransferase, which is at least in part recruited by heterochromatin protein 1.[76]

Bivalent promoters

Analysis of histone modifications in embryonic stem cells (and other stem cells) revealed many gene promoters carrying both H3K4Me3 and H3K27Me3, in other words these promoters display both activating and repressing marks simultaneously. This peculiar combination of modifications marks genes that are poised for transcription; they are not required in stem cells, but are rapidly required after differentiation into some lineages. Once the cell starts to differentiate, these bivalent promoters are resolved to either active or repressive states depending on the chosen lineage.[78]

Other functions

DNA damage repair

Marking sites of DNA damage is an important function for histone modifications. Without a repair marker, DNA would get destroyed by damage accumulated from sources such as the ultraviolet radiation of the sun.

- Phosphorylation of H2AX at serine 139 (γH2AX)

- Phosphorylated H2AX (also known as gamma H2AX) is a marker for DNA double strand breaks,[79] and forms part of the response to DNA damage.[32][80] H2AX is phosphorylated early after detection of DNA double strand break, and forms a domain extending many kilobases either side of the damage.[79][81][82] Gamma H2AX acts as a binding site for the protein MDC1, which in turn recruits key DNA repair proteins[83] (this complex topic is well reviewed in[84]) and as such, gamma H2AX forms a vital part of the machinery that ensures genome stability.

- Acetylation of H3 lysine 56 (H3K56Ac)

- H3K56Acx is required for genome stability.[85][86] H3K56 is acetylated by the p300/Rtt109 complex,[87][88][89] but is rapidly deacetylated around sites of DNA damage. H3K56 acetylation is also required to stabilise stalled replication forks, preventing dangerous replication fork collapses.[90][91] Although in general mammals make far greater use of histone modifications than microorganisms, a major role of H3K56Ac in DNA replication exists only in fungi, and this has become a target for antibiotic development.[92]

- Trimethylation of H3 lysine 36 (H3K36me3)

- H3K36me3 has the ability to recruit the MSH2-MSH6 (hMutSα) complex of the DNA mismatch repair pathway.[93] Consistently, regions of the human genome with high levels of H3K36me3 accumulate less somatic mutations due to mismatch repair activity.[94]

Chromosome condensation

- Phosphorylation of H3 at serine 10 (phospho-H3S10)

- The mitotic kinase aurora B phosphorylates histone H3 at serine 10, triggering a cascade of changes that mediate mitotic chromosome condensation.[95][96] Condensed chromosomes therefore stain very strongly for this mark, but H3S10 phosphorylation is also present at certain chromosome sites outside mitosis, for example in pericentric heterochromatin of cells during G2. H3S10 phosphorylation has also been linked to DNA damage caused by R-loop formation at highly transcribed sites.[97]

- Phosphorylation H2B at serine 10/14 (phospho-H2BS10/14)

- Phosphorylation of H2B at serine 10 (yeast) or serine 14 (mammals) is also linked to chromatin condensation, but for the very different purpose of mediating chromosome condensation during apoptosis.[98][99] This mark is not simply a late acting bystander in apoptosis as yeast carrying mutations of this residue are resistant to hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptotic cell death.

Addiction

Epigenetic modifications of histone tails in specific regions of the brain are of central importance in addictions.[100][101][102] Once particular epigenetic alterations occur, they appear to be long lasting "molecular scars" that may account for the persistence of addictions.[100]

Cigarette smokers (about 15% of the US population) are usually addicted to nicotine.[103] After 7 days of nicotine treatment of mice, acetylation of both histone H3 and histone H4 was increased at the FosB promoter in the nucleus accumbens of the brain, causing 61% increase in FosB expression.[104] This would also increase expression of the splice variant Delta FosB. In the nucleus accumbens of the brain, Delta FosB functions as a "sustained molecular switch" and "master control protein" in the development of an addiction.[105][106]

About 7% of the US population is addicted to alcohol. In rats exposed to alcohol for up to 5 days, there was an increase in histone 3 lysine 9 acetylation in the pronociceptin promoter in the brain amygdala complex. This acetylation is an activating mark for pronociceptin. The nociceptin/nociceptin opioid receptor system is involved in the reinforcing or conditioning effects of alcohol.[107]

Methamphetamine addiction occurs in about 0.2% of the US population.[108] Chronic methamphetamine use causes methylation of the lysine in position 4 of histone 3 located at the promoters of the c-fos and the C-C chemokine receptor 2 (ccr2) genes, activating those genes in the nucleus accumbens (NAc).[109] c-fos is well known to be important in addiction.[110] The ccr2 gene is also important in addiction, since mutational inactivation of this gene impairs addiction.[109]

Histone chaperones

Histone chaperones are specialized proteins that assist in the proper handling, transport, and assembly of histones, preventing their aggregation and ensuring their appropriate deposition onto DNA. These proteins play a crucial role in regulating nucleosome assembly and disassembly, influencing transcriptional activity, DNA replication, and repair. Unlike enzymatic chromatin remodeling, histone chaperones function by binding histones in a regulated manner, modulating chromatin structure without direct catalytic activity.[111]

One key function of histone chaperones is maintaining a reservoir of histones, regulating their supply to ensure proper chromatin formation. During DNA replication and transcription, histone chaperones such as ASF1 and FACT facilitate nucleosome reassembly, ensuring the preservation of histone modifications that define cellular identity. Moreover, histone chaperones contribute to nucleosome disassembly in response to cellular stress or DNA damage, thereby allowing access to repair machinery.

Histone chaperones also participate in the selective deposition of histone variants, which are functionally distinct from canonical histones. For example, HIRA is a chaperone that specifically deposits the histone variant H3.3, a marker of active chromatin regions. Similarly, CAF-1 is responsible for incorporating H3.1 and H3.2 into newly replicated DNA, highlighting the functional specialization within chaperone networks.[11]

Given their critical roles, misregulation of histone chaperones has been implicated in diseases such as cancer. Aberrant chaperone activity can lead to improper histone deposition, genome instability, and altered gene expression, contributing to tumorigenesis. Current research is exploring histone chaperones as potential therapeutic targets, particularly in cancers characterized by disrupted chromatin landscapes.[111]

Chaperone networks

The coordinated action of multiple histone chaperones forms an intricate network responsible for histone transport, Chromatin assembly factor 1, and genome maintenance. Chaperone networks facilitate the transport of histones which are synthesized in the cytoplasm and must be escorted to the cell nucleus. This network ensures histones are deposited at the appropriate genomic locations, maintaining chromatin integrity and function.[112]

Histone chaperones play a crucial role in responding to DNA damage by regulating chromatin accessibility. For example, in response to double strand breaks, chaperones such as FACT and ASF1 help disassemble nucleosomes at damage sites, allowing repair factors to access the lesion. Once repair is completed, these chaperones facilitate the reassembly of nucleosomes, restoring chromatin structure and ensuring epigenetic information is maintained.[113]

In addition to their role in genome stability, histone chaperones contribute to epigenetic inheritance. During cell division, chromatin states must be faithfully propagated to daughter cells. Chaperones help distribute parental histones onto newly synthesized DNA strands, preserving histone modifications and ensuring continuity of cellular identity. Disruptions in these processes can lead to epigenetic abnormalities associated with developmental disorders.[112]

Synthesis

The first step of chromatin structure duplication is the synthesis of histone proteins: H1, H2A, H2B, H3, H4. These proteins are synthesized during S phase of the cell cycle. There are different mechanisms which contribute to the increase of histone synthesis.

Yeast

Yeast carry one or two copies of each histone gene, which are not clustered but rather scattered throughout chromosomes. Histone gene transcription is controlled by multiple gene regulatory proteins such as transcription factors which bind to histone promoter regions. In budding yeast, the candidate gene for activation of histone gene expression is SBF. SBF is a transcription factor that is activated in late G1 phase, when it dissociates from its repressor Whi5. This occurs when Whi5 is phosphorylated by Cdc8 which is a G1/S Cdk.[114] Suppression of histone gene expression outside of S phases is dependent on Hir proteins which form inactive chromatin structure at the locus of histone genes, causing transcriptional activators to be blocked.[115][116]

Metazoan

In metazoans the increase in the rate of histone synthesis is due to the increase in processing of pre-mRNA to its mature form as well as decrease in mRNA degradation; this results in an increase of active mRNA for translation of histone proteins. The mechanism for mRNA activation has been found to be the removal of a segment of the 3' end of the mRNA strand, and is dependent on association with stem-loop binding protein (SLBP).[117] SLBP also stabilizes histone mRNAs during S phase by blocking degradation by the 3'hExo nuclease.[118] SLBP levels are controlled by cell-cycle proteins, causing SLBP to accumulate as cells enter S phase and degrade as cells leave S phase. SLBP are marked for degradation by phosphorylation at two threonine residues by cyclin dependent kinases, possibly cyclin A/ cdk2, at the end of S phase.[119] Metazoans also have multiple copies of histone genes clustered on chromosomes which are localized in structures called Cajal bodies as determined by genome-wide chromosome conformation capture analysis (4C-Seq).[120]

Link between cell-cycle control and synthesis

Nuclear protein ataxia-telangiectasia (NPAT), also known as nuclear protein coactivator of histone transcription, is a transcription factor which activates histone gene transcription on chromosomes 1 and 6 of human cells. NPAT is also a substrate of cyclin E-Cdk2, which is required for the transition between G1 phase and S phase. NPAT activates histone gene expression only after it has been phosphorylated by the G1/S-Cdk cyclin E-Cdk2 in early S phase.[121] This shows an important regulatory link between cell-cycle control and histone synthesis.

History

Histones were discovered in 1884 by Albrecht Kossel.[122] The word "histone" dates from the late 19th century and is derived from the German word histon, a word itself of uncertain origin, perhaps from Ancient Greek ἵστημι (hístēmi, "make stand") or ἱστός (histós, "loom").

In the early 1960s, before the types of histones were known and before histones were known to be highly conserved across taxonomically diverse organisms, James F. Bonner and his collaborators began a study of these proteins that were known to be tightly associated with the DNA in the nucleus of higher organisms.[123] Bonner and his postdoctoral fellow Ru Chih C. Huang showed that isolated chromatin would not support RNA transcription in the test tube, but if the histones were extracted from the chromatin, RNA could be transcribed from the remaining DNA.[124] Their paper became a citation classic.[125] Paul T'so and James Bonner had called together a World Congress on Histone Chemistry and Biology in 1964, in which it became clear that there was no consensus on the number of kinds of histone and that no one knew how they would compare when isolated from different organisms.[126][123] Bonner and his collaborators then developed methods to separate each type of histone, purified individual histones, compared amino acid compositions in the same histone from different organisms, and compared amino acid sequences of the same histone from different organisms in collaboration with Emil Smith from UCLA.[127] For example, they found Histone IV sequence to be highly conserved between peas and calf thymus.[127] However, their work on the biochemical characteristics of individual histones did not reveal how the histones interacted with each other or with DNA to which they were tightly bound.[126]

Also in the 1960s, Vincent Allfrey and Alfred Mirsky had suggested, based on their analyses of histones, that acetylation and methylation of histones could provide a transcriptional control mechanism, but did not have available the kind of detailed analysis that later investigators were able to conduct to show how such regulation could be gene-specific.[128] Until the early 1990s, histones were dismissed by most as inert packing material for eukaryotic nuclear DNA, a view based in part on the models of Mark Ptashne and others, who believed that transcription was activated by protein-DNA and protein-protein interactions on largely naked DNA templates, as is the case in bacteria.

During the 1980s, Yahli Lorch and Roger Kornberg[129] showed that a nucleosome on a core promoter prevents the initiation of transcription in vitro, and Michael Grunstein[130] demonstrated that histones repress transcription in vivo, leading to the idea of the nucleosome as a general gene repressor. Relief from repression is believed to involve both histone modification and the action of chromatin-remodeling complexes. Vincent Allfrey and Alfred Mirsky had earlier proposed a role of histone modification in transcriptional activation,[131] regarded as a molecular manifestation of epigenetics. Michael Grunstein[132] and David Allis[133] found support for this proposal, in the importance of histone acetylation for transcription in yeast and the activity of the transcriptional activator Gcn5 as a histone acetyltransferase.

The discovery of the H5 histone appears to date back to the 1970s,[134] and it is now considered an isoform of Histone H1.[2][4][5][6]

See also

References

- ↑ Collins Dictionary of Human Biology. Glasgow: HarperCollins. 2006. ISBN 978-0-00-722134-9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. 2005. ISBN 978-0-7167-4339-2. https://archive.org/details/lehningerprincip00lehn_0.

- ↑ "Histone H2A variants H2AX and H2AZ". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 12 (2): 162–9. April 2002. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(02)00282-4. PMID 11893489. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959437X02002824.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Histone Variants Database 2.0". National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/histonedb/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Recognition and classification of histones using support vector machine". Journal of Computational Biology 13 (1): 102–12. 2006. doi:10.1089/cmb.2006.13.102. PMID 16472024. http://eprints.ucm.es/9328/1/31.Reche_etal_MI_2006.pdf. Retrieved 2019-03-23.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Basic Genetics. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. 1988. ISBN 978-0-86720-090-4. https://archive.org/details/basicgenetics0000hart.

- ↑ "Histone structure and nucleosome stability". Expert Review of Proteomics 2 (5): 719–29. October 2005. doi:10.1586/14789450.2.5.719. PMID 16209651.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution". Nature 389 (6648): 251–60. September 1997. doi:10.1038/38444. PMID 9305837. Bibcode: 1997Natur.389..251L. https://www.nature.com/articles/38444. PDB: 1AOI

- ↑ DNA simplified: the hitchhiker's guide to DNA. Washington, D.C.: AACC Press. 1996. ISBN 978-0-915274-84-0.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "A standardized nomenclature for mammalian histone genes". Epigenetics & Chromatin 15 (1). October 2022. doi:10.1186/s13072-022-00467-2. PMID 36180920.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Histone exchange, chromatin structure and the regulation of transcription". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 16 (3): 178–189. March 2015. doi:10.1038/nrm3941. PMID 25650798.

- ↑ "Histone variants: emerging players in cancer biology". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 71 (3): 379–404. February 2014. doi:10.1007/s00018-013-1343-z. PMID 23652611.

- ↑ "Histone H3.3 maintains genome integrity during mammalian development". Genes & Development 29 (13): 1377–1392. July 2015. doi:10.1101/gad.264150.115. PMID 26159997.

- ↑ "HistoneDB 2.0: a histone database with variants--an integrated resource to explore histones and their variants". Database 2016. 2016. doi:10.1093/database/baw014. PMID 26989147.

- ↑ "MS_HistoneDB, a manually curated resource for proteomic analysis of human and mouse histones". Epigenetics & Chromatin 10. 2017. doi:10.1186/s13072-016-0109-x. PMID 28096900.

- ↑ "Evidence for a human histone gene cluster containing H2B and H2A pseudogenes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 81 (7): 1936–1940. April 1984. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.7.1936. PMID 6326092. Bibcode: 1984PNAS...81.1936M.

- ↑ "Association of a human H1 histone gene with an H2A pseudogene and genes encoding H2B.1 and H3.1 histones". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 52 (4): 375–383. August 1993. doi:10.1002/jcb.240520402. PMID 8227173.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "On the origin of the histone fold". BMC Structural Biology 7. March 2007. doi:10.1186/1472-6807-7-17. PMID 17391511.

- ↑ "Structure of histone-based chromatin in Archaea". Science 357 (6351): 609–612. August 2017. doi:10.1126/science.aaj1849. PMID 28798133. Bibcode: 2017Sci...357..609M.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Structure and function of archaeal histones". PLOS Genetics 14 (9). September 2018. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007582. PMID 30212449. Bibcode: 2018BpJ...114..446H.

- ↑ "Long distance PELDOR measurements on the histone core particle". Journal of the American Chemical Society 131 (4): 1348–9. February 2009. doi:10.1021/ja807918f. PMID 19138067. Bibcode: 2009JAChS.131.1348W.

- ↑ "The tale beyond the tail: histone core domain modifications and the regulation of chromatin structure". Nucleic Acids Research 34 (9): 2653–62. 19 May 2006. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl338. PMID 16714444.

- ↑ "Scratching the (lateral) surface of chromatin regulation by histone modifications". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 20 (6): 657–61. June 2013. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2581. PMID 23739170. https://www.nature.com/articles/nsmb.2581.

- ↑ Fundamental Molecular Biology (Second ed.). United States of America: John Wiley & Sons. 2012. pp. 102. ISBN 978-1-118-05981-4.

- ↑ "Those amazing dinoflagellate chromosomes". Cell Research 13 (4): 215–7. August 2003. doi:10.1038/sj.cr.7290166. PMID 12974611.

- ↑ "Chromatin: packaging without nucleosomes". Current Biology 22 (24): R1040-3. December 2012. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.052. PMID 23257187. Bibcode: 2012CBio...22R1040T.

- ↑ "Origin of H1 linker histones". FASEB Journal 15 (1): 34–42. January 2001. doi:10.1096/fj.00-0237rev. PMID 11149891.

- ↑ "The origin of chromosomal histones in a 30S ribosomal protein". Gene 726. February 2020. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2019.144155. PMID 31629821. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378111919308145.

- ↑ "Nuclear and chromatin composition of mammalian gametes and early embryos". Biochemistry and Cell Biology 70 (10–11): 856–66. 1992. doi:10.1139/o92-134. PMID 1297351. Bibcode: 1992BCB....70..856C. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/o92-134.

- ↑ "Variant histone H2A.Z is globally localized to the promoters of inactive yeast genes and regulates nucleosome positioning". PLOS Biology 3 (12). December 2005. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030384. PMID 16248679.

- ↑ "Precise deposition of histone H2A.Z in chromatin for genome expression and maintenance". Biochim Biophys Acta 1819 (3–4): 290–302. October 2011. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.10.004. PMID 22027408. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1874939911001805.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "A critical role for histone H2AX in recruitment of repair factors to nuclear foci after DNA damage". Current Biology 10 (15): 886–95. 2000. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00610-2. PMID 10959836. Bibcode: 2000CBio...10..886P.

- ↑ "The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly". Molecular Cell 9 (6): 1191–200. June 2002. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00542-7. PMID 12086617.

- ↑ Stewart, Alison (1990). "The functional organizaton [sic of chromosomes and the nucleos"] (in en). Trends in Genetics 6 (12): 377–379. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(90)90282-B. PMID 2087778. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/016895259090282B.

- ↑ "The language of covalent histone modifications". Nature 403 (6765): 41–5. January 2000. doi:10.1038/47412. PMID 10638745. Bibcode: 2000Natur.403...41S. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000Natur.403...41S/abstract.

- ↑ "Translating the histone code". Science 293 (5532): 1074–80. August 2001. doi:10.1126/science.1063127. PMID 11498575. http://www.gs.washington.edu/academics/courses/braun/55104/readings/jenuwein.pdf.

- ↑ "Immunohistochemical Analysis of Histone H3 Modifications in Germ Cells during Mouse Spermatogenesis". Acta Histochemica et Cytochemica 44 (4): 183–90. August 2011. doi:10.1267/ahc.11027. PMID 21927517.

- ↑ "Histone H3K4 demethylases are essential in development and differentiation". Biochemistry and Cell Biology 85 (4): 435–43. August 2007. doi:10.1139/o07-057. PMID 17713579. Bibcode: 2007BCB....85..057B. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/O07-057.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 39.7 "High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome". Cell 129 (4): 823–37. May 2007. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. PMID 17512414.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 "DOT1L/KMT4 recruitment and H3K79 methylation are ubiquitously coupled with gene transcription in mammalian cells". Molecular and Cellular Biology 28 (8): 2825–39. April 2008. doi:10.1128/MCB.02076-07. PMID 18285465.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Determination of enriched histone modifications in non-genic portions of the human genome". BMC Genomics 10. March 2009. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-143. PMID 19335899.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 "The landscape of histone modifications across 1% of the human genome in five human cell lines". Genome Research 17 (6): 691–707. June 2007. doi:10.1101/gr.5704207. PMID 17567990.

- ↑ "H4K20me3 co-localizes with activating histone modifications at transcriptionally dynamic regions in embryonic stem cells". BMC Genomics 19 (1). July 2018. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-4886-4. PMID 29969988.

- ↑ "H3 lysine 4 is acetylated at active gene promoters and is regulated by H3 lysine 4 methylation". PLOS Genetics 7 (3). March 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001354. PMID 21483810.

- ↑ "Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (50): 21931–6. December 2010. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016071107. PMID 21106759.

- ↑ "Histone serotonylation is a permissive modification that enhances TFIID binding to H3K4me3". Nature 567 (7749): 535–539. March 2019. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1024-7. PMID 30867594. Bibcode: 2019Natur.567..535F.

- ↑ "Citrullination regulates pluripotency and histone H1 binding to chromatin". Nature 507 (7490): 104–8. March 2014. doi:10.1038/nature12942. PMID 24463520. PMC 4843970. Bibcode: 2014Natur.507..104C. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/254537.

- ↑ "Histone deimination antagonizes arginine methylation". Cell 118 (5): 545–53. September 2004. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.020. PMID 15339660.

- ↑ "The Paf1 complex is required for histone H3 methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p: linking transcriptional elongation to histone methylation". Molecular Cell 11 (3): 721–9. March 2003. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00091-1. PMID 12667454.

- ↑ "Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity". Molecular Cell 11 (3): 709–19. March 2003. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00092-3. PMID 12667453.

- ↑ "Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse". Cell 120 (2): 169–81. January 2005. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.001. PMID 15680324.

- ↑ "COMPASS, a histone H3 (Lysine 4) methyltransferase required for telomeric silencing of gene expression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (13): 10753–5. March 2002. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200023200. PMID 11805083.

- ↑ "The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Set1 complex includes an Ash2 homologue and methylates histone 3 lysine 4". The EMBO Journal 20 (24): 7137–48. December 2001. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.24.7137. PMID 11742990.

- ↑ "A trithorax-group complex purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for methylation of histone H3". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (1): 90–4. January 2002. doi:10.1073/pnas.221596698. PMID 11752412. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99...90N.

- ↑ "The Bur1/Bur2 complex is required for histone H2B monoubiquitination by Rad6/Bre1 and histone methylation by COMPASS". Molecular Cell 20 (4): 589–99. November 2005. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.010. PMID 16307922.

- ↑ "Regulation of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme hHR6A by CDK-mediated phosphorylation". The EMBO Journal 21 (8): 2009–18. April 2002. doi:10.1093/emboj/21.8.2009. PMID 11953320.

- ↑ "Rad6-dependent ubiquitination of histone H2B in yeast". Science 287 (5452): 501–4. January 2000. doi:10.1126/science.287.5452.501. PMID 10642555. Bibcode: 2000Sci...287..501R. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.287.5452.501.

- ↑ "Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast". Nature 418 (6893): 104–8. July 2002. doi:10.1038/nature00883. PMID 12077605. Bibcode: 2002Natur.418..104S. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature00883.

- ↑ "Methylation of histone H3 by COMPASS requires ubiquitination of histone H2B by Rad6". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (32): 28368–71. August 2002. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200348200. PMID 12070136.

- ↑ "Set2 is a nucleosomal histone H3-selective methyltransferase that mediates transcriptional repression". Molecular and Cellular Biology 22 (5): 1298–306. March 2002. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.5.1298-1306.2002. PMID 11839797.

- ↑ "Association of the histone methyltransferase Set2 with RNA polymerase II plays a role in transcription elongation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (51): 49383–8. December 2002. doi:10.1074/jbc.M209294200. PMID 12381723.

- ↑ "Histone H3 methylation by Set2 directs deacetylation of coding regions by Rpd3S to suppress spurious intragenic transcription". Cell 123 (4): 581–92. November 2005. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.023. PMID 16286007.

- ↑ "Cotranscriptional set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 recruits a repressive Rpd3 complex". Cell 123 (4): 593–605. November 2005. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.025. PMID 16286008.

- ↑ "Eaf3 chromodomain interaction with methylated H3-K36 links histone deacetylation to Pol II elongation". Molecular Cell 20 (6): 971–8. December 2005. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.021. PMID 16364921.

- ↑ "Histone methyltransferase activity associated with a human multiprotein complex containing the Enhancer of Zeste protein". Genes & Development 16 (22): 2893–905. November 2002. doi:10.1101/gad.1035902. PMID 12435631.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing". Science 298 (5595): 1039–43. November 2002. doi:10.1126/science.1076997. PMID 12351676. Bibcode: 2002Sci...298.1039C. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1076997.

- ↑ "Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B link ubiquitylation of histone H2A to heritable gene silencing and X inactivation". Developmental Cell 7 (5): 663–76. November 2004. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.005. PMID 15525528.

- ↑ "Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing". Nature 431 (7010): 873–8. October 2004. doi:10.1038/nature02985. PMID 15386022. Bibcode: 2004Natur.431..873W.

- ↑ "RYBP-PRC1 complexes mediate H2A ubiquitylation at polycomb target sites independently of PRC2 and H3K27me3". Cell 148 (4): 664–78. February 2012. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.029. PMID 22325148.

- ↑ "PCGF homologs, CBX proteins, and RYBP define functionally distinct PRC1 family complexes". Molecular Cell 45 (3): 344–56. February 2012. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.002. PMID 22325352.

- ↑ "RNAi-mediated targeting of heterochromatin by the RITS complex". Science 303 (5658): 672–6. January 2004. doi:10.1126/science.1093686. PMID 14704433. Bibcode: 2004Sci...303..672V.

- ↑ "Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases". Nature 406 (6796): 593–9. August 2000. doi:10.1038/35020506. PMID 10949293. Bibcode: 2000Natur.406..593R. https://www.nature.com/articles/35020506.

- ↑ "Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain". Nature 410 (6824): 120–4. March 2001. doi:10.1038/35065138. PMID 11242054. Bibcode: 2001Natur.410..120B. https://www.nature.com/articles/35065138.

- ↑ "Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins". Nature 410 (6824): 116–20. March 2001. doi:10.1038/35065132. PMID 11242053. Bibcode: 2001Natur.410..116L. https://www.nature.com/articles/35065132.

- ↑ "Binding of DNA-bending non-histone proteins destabilizes regular 30-nm chromatin structure". PLOS Computational Biology 13 (1). January 2017. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005365. PMID 28135276. Bibcode: 2017PLSCB..13E5365B.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "A silencing pathway to induce H3-K9 and H4-K20 trimethylation at constitutive heterochromatin". Genes & Development 18 (11): 1251–62. June 2004. doi:10.1101/gad.300704. PMID 15145825.

- ↑ "Heterochromatin and tri-methylated lysine 20 of histone H4 in animals". Journal of Cell Science 117 (Pt 12): 2491–501. May 2004. doi:10.1242/jcs.01238. PMID 15128874.

- ↑ "A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells". Cell 125 (2): 315–26. April 2006. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. PMID 16630819.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (10): 5858–68. March 1998. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. PMID 9488723.

- ↑ "Genomic instability in mice lacking histone H2AX". Science 296 (5569): 922–7. May 2002. doi:10.1126/science.1069398. PMID 11934988. Bibcode: 2002Sci...296..922C.

- ↑ "Distribution and dynamics of chromatin modification induced by a defined DNA double-strand break". Current Biology 14 (19): 1703–11. October 2004. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.047. PMID 15458641. Bibcode: 2004CBio...14.1703S.

- ↑ "Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo". The Journal of Cell Biology 146 (5): 905–16. September 1999. doi:10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. PMID 10477747.

- ↑ "MDC1 is a mediator of the mammalian DNA damage checkpoint". Nature 421 (6926): 961–6. February 2003. doi:10.1038/nature01446. PMID 12607005. Bibcode: 2003Natur.421..961S. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature01446.

- ↑ "Assembly and function of DNA double-strand break repair foci in mammalian cells". DNA Repair 9 (12): 1219–28. December 2010. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.010. PMID 21035408. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1568786410003150.

- ↑ "Characterization of lysine 56 of histone H3 as an acetylation site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (28): 25949–52. July 2005. doi:10.1074/jbc.C500181200. PMID 15888442.

- ↑ "A role for cell-cycle-regulated histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation in the DNA damage response". Nature 436 (7048): 294–8. July 2005. doi:10.1038/nature03714. PMID 16015338. Bibcode: 2005Natur.436..294M. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature03714.

- ↑ "Yeast Rtt109 promotes genome stability by acetylating histone H3 on lysine 56". Science 315 (5812): 649–52. February 2007. doi:10.1126/science.1135862. PMID 17272722. Bibcode: 2007Sci...315..649D.

- ↑ "Rtt109 acetylates histone H3 lysine 56 and functions in DNA replication". Science 315 (5812): 653–5. February 2007. doi:10.1126/science.1133234. PMID 17272723. Bibcode: 2007Sci...315..653H. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1133234.

- ↑ "CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56". Nature 459 (7243): 113–7. May 2009. doi:10.1038/nature07861. PMID 19270680. Bibcode: 2009Natur.459..113D.

- ↑ "Acetylation of lysine 56 of histone H3 catalyzed by RTT109 and regulated by ASF1 is required for replisome integrity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (39): 28587–96. September 2007. doi:10.1074/jbc.M702496200. PMID 17690098.

- ↑ "Histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation and the response to DNA replication fork damage". Molecular and Cellular Biology 32 (1): 154–72. January 2012. doi:10.1128/MCB.05415-11. PMID 22025679.

- ↑ "Modulation of histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation as an antifungal therapeutic strategy". Nature Medicine 16 (7): 774–80. July 2010. doi:10.1038/nm.2175. PMID 20601951.

- ↑ "The histone mark H3K36me3 regulates human DNA mismatch repair through its interaction with MutSα". Cell 153 (3): 590–600. April 2013. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.025. PMID 23622243.

- ↑ "Clustered Mutation Signatures Reveal that Error-Prone DNA Repair Targets Mutations to Active Genes". Cell 170 (3): 534–547.e23. July 2017. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.003. PMID 28753428.

- ↑ "A cascade of histone modifications induces chromatin condensation in mitosis". Science 343 (6166): 77–80. January 2014. doi:10.1126/science.1244508. PMID 24385627. Bibcode: 2014Sci...343...77W. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1244508.

- ↑ "Regulation of chromatin structure by histone H3S10 phosphorylation". Chromosome Research 14 (4): 393–404. 2006. doi:10.1007/s10577-006-1063-4. PMID 16821135. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10577-006-1063-4.

- ↑ "R loops are linked to histone H3 S10 phosphorylation and chromatin condensation". Molecular Cell 52 (4): 583–90. November 2013. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.006. PMID 24211264.

- ↑ "Apoptotic phosphorylation of histone H2B is mediated by mammalian sterile twenty kinase". Cell 113 (4): 507–17. May 2003. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00355-6. PMID 12757711.

- ↑ "Sterile 20 kinase phosphorylates histone H2B at serine 10 during hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis in S. cerevisiae". Cell 120 (1): 25–36. January 2005. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.016. PMID 15652479.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 12 (11): 623–637. October 2011. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMID 21989194.

- ↑ "Histone-mediated epigenetics in addiction". Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science (Academic Press) 128: 51–87. 2014. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800977-2.00003-6. ISBN 978-0-12-800977-2. PMID 25410541.

- ↑ "Epigenetic regulation in substance use disorders". Current Psychiatry Reports 12 (2): 145–153. April 2010. doi:10.1007/s11920-010-0099-5. PMID 20425300.

- ↑ "Is nicotine addictive?". https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/tobacco-nicotine-e-cigarettes/nicotine-addictive.

- ↑ "Molecular mechanism for a gateway drug: epigenetic changes initiated by nicotine prime gene expression by cocaine". Science Translational Medicine 3 (107): 107ra109. November 2011. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003062. PMID 22049069.

- ↑ "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 40 (6): 428–37. November 2014. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/00952990.2014.933840?journalCode=iada20.

- ↑ "DeltaFosB: a sustained molecular switch for addiction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98 (20): 11042–6. September 2001. doi:10.1073/pnas.191352698. PMID 11572966. Bibcode: 2001PNAS...9811042N.

- ↑ "Ethanol induces epigenetic modulation of prodynorphin and pronociceptin gene expression in the rat amygdala complex". Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 49 (2): 312–9. February 2013. doi:10.1007/s12031-012-9829-y. PMID 22684622. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12031-012-9829-y.

- ↑ "What is the scope of methamphetamine abuse in the United States?". https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/methamphetamine/what-scope-methamphetamine-abuse-in-united-states.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 "Epigenetic landscape of amphetamine and methamphetamine addiction in rodents". Epigenetics 10 (7): 574–80. 2015. doi:10.1080/15592294.2015.1055441. PMID 26023847.

- ↑ "Using c-fos to study neuronal ensembles in corticostriatal circuitry of addiction". Brain Research 1628 (Pt A): 157–73. December 2015. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.11.005. PMID 25446457.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 "Histone chaperones: assisting histone traffic and nucleosome dynamics". Annual Review of Biochemistry 83 (1): 487–517. 2014-06-02. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035536. PMID 24905786.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 "Histone chaperones: A multinodal highway network inside the cell". Molecular Cell 83 (7): 1024–1026. April 2023. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2023.03.004. PMID 37028413.

- ↑ "Reshaping chromatin after DNA damage: the choreography of histone proteins". Journal of Molecular Biology 427 (3): 626–636. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2014.05.025. PMID 24887097.

- ↑ "Cln3 activates G1-specific transcription via phosphorylation of the SBF bound repressor Whi5". Cell 117 (7): 887–98. June 2004. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.025. PMID 15210110.

- ↑ "Identification of a new set of cell cycle-regulatory genes that regulate S-phase transcription of histone genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Molecular and Cellular Biology 12 (11): 5249–59. November 1992. doi:10.1128/mcb.12.11.5249. PMID 1406694.

- ↑ "A role for transcriptional repressors in targeting the yeast Swi/Snf complex". Molecular Cell 4 (1): 75–83. July 1999. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80189-6. PMID 10445029.

- ↑ "A novel zinc finger protein is associated with U7 snRNP and interacts with the stem-loop binding protein in the histone pre-mRNP to stimulate 3'-end processing". Genes & Development 16 (1): 58–71. January 2002. doi:10.1101/gad.932302. PMID 11782445.

- ↑ "A 3' exonuclease that specifically interacts with the 3' end of histone mRNA". Molecular Cell 12 (2): 295–305. August 2003. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00278-8. PMID 14536070.

- ↑ "Phosphorylation of stem-loop binding protein (SLBP) on two threonines triggers degradation of SLBP, the sole cell cycle-regulated factor required for regulation of histone mRNA processing, at the end of S phase". Molecular and Cellular Biology 23 (5): 1590–601. March 2003. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.5.1590-1601.2003. PMID 12588979.

- ↑ "Cajal bodies are linked to genome conformation". Nature Communications 7. March 2016. doi:10.1038/ncomms10966. PMID 26997247. Bibcode: 2016NatCo...710966W.

- ↑ "NPAT links cyclin E-Cdk2 to the regulation of replication-dependent histone gene transcription". Genes & Development 14 (18): 2283–97. September 2000. doi:10.1101/GAD.827700. PMID 10995386.

- ↑ "Histone Chemistry: the Pioneers". The Nucleohistones. San Francisco, London, and Amsterdam: Holden-Day, Inc. 1965.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 "Chapters from my life". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 45: 1–23. 1994. doi:10.1146/annurev.pp.45.060194.000245.

- ↑ "Histone, a suppressor of chromosomal RNA synthesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 48 (7): 1216–22. July 1962. doi:10.1073/pnas.48.7.1216. PMID 14036409. Bibcode: 1962PNAS...48.1216H.

- ↑ "Huang R C & Bonner J. Histone, a suppressor of chromosomal RNA synthesis. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. US 48:1216-22, 1962.". Citation Classics (12): 79. 20 March 1978. http://garfield.library.upenn.edu/classics1978/A1978EP01300002.pdf.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 James Bonner and Paul T'so (1965) The Nucleohistones. Holden-Day Inc, San Francisco, London, Amsterdam.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 "Calf and pea histone IV. 3. Complete amino acid sequence of pea seedling histone IV; comparison with the homologous calf thymus histone". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 244 (20): 5669–79. October 1969. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)63612-9. PMID 5388597.

- ↑ "Acetylation and methylation of histones and their possible role in the regulation of RNA synthesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 51 (5): 786–94. May 1964. doi:10.1073/pnas.51.5.786. PMID 14172992. Bibcode: 1964PNAS...51..786A.

- ↑ "Nucleosomes inhibit the initiation of transcription but allow chain elongation with the displacement of histones". Cell 49 (2): 203–10. April 1987. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90561-7. PMID 3568125.

- ↑ "Extremely conserved histone H4 N terminus is dispensable for growth but essential for repressing the silent mating loci in yeast". Cell 55 (1): 27–39. October 1988. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90006-2. PMID 3048701. https://www.cell.com/cell/pdf/0092-8674(88)90006-2.pdf?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2F0092867488900062%3Fshowall%3Dtrue.

- ↑ "RNA synthesis and histone acetylation during the course of gene activation in lymphocytes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 55 (4): 805–12. April 1966. doi:10.1073/pnas.55.4.805. PMID 5219687. Bibcode: 1966PNAS...55..805P.

- ↑ "Yeast histone H4 N-terminal sequence is required for promoter activation in vivo". Cell 65 (6): 1023–31. June 1991. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90554-c. PMID 2044150. https://www.cell.com/cell/pdf/0092-8674(91)90554-C.pdf?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2F009286749190554C%3Fshowall%3Dtrue.

- ↑ "Tetrahymena histone acetyltransferase A: a homolog to yeast Gcn5p linking histone acetylation to gene activation". Cell 84 (6): 843–51. March 1996. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81063-6. PMID 8601308.

- ↑ "The conformation of histone H5. Isolation and characterisation of the globular segment". European Journal of Biochemistry 88 (2): 363–71. August 1978. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12457.x. PMID 689022.

External links

- HistoneDB 2.0 - Database of histones and variants at NCBI

- Chromatin, Histones & Cathepsin; PMAP The Proteolysis Map-animation

|