Biology:Euryarchaeota

| Euryarchaeota | |

|---|---|

| |

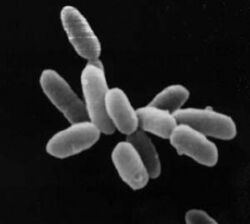

| Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1, each cell about 5 µm in length. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Archaea |

| Kingdom: | Euryarchaeota Woese, Kandler & Wheelis, 1990[1] |

| Phyla[2] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Euryarchaeota (from Ancient Greek εὐρύς eurús, "broad, wide") is a phylum of archaea.[3] Euryarchaeota are highly diverse and include methanogens, which produce methane and are often found in intestines, halobacteria, which survive extreme concentrations of salt, and some extremely thermophilic aerobes and anaerobes, which generally live at temperatures between 41 and 122 °C. They are separated from the other archaeans based mainly on rRNA sequences and their unique DNA polymerase.[4]

Description

The Euryarchaeota are diverse in appearance and metabolic properties. The phylum contains organisms of a variety of shapes, including both rods and cocci. Euryarchaeota may appear either gram-positive or gram-negative depending on whether pseudomurein is present in the cell wall.[5] Euryarchaeota also demonstrate diverse lifestyles, including methanogens, halophiles, sulfate-reducers, and extreme thermophiles in each.[5] Others live in the ocean, suspended with plankton and bacteria. Although these marine euryarchaeota are difficult to culture and study in a lab, genomic sequencing suggests that they are motile heterotrophs.[6]

Though it was previously thought that euryarchaeota only lived in extreme environments (in terms of temperature, salt content and/or pH), a paper by Korzhenkov et al published in January 2019 showed that euryarchaeota also live in moderate environments, such as low-temperature acidic environments. In some cases, euryarchaeota outnumbered the bacteria present.[7] Euryarchaeota have also been found in other moderate environments such as water springs, marshlands, soil and rhizospheres.[8] Some euryarchaeota are highly adaptable; an order called Halobacteriales are usually found in extremely salty and sulfur-rich environments but can also grow in salt concentrations as low as that of seawater 2.5%.[8] In rhizospheres, the presence of euryarchaeota seems to be dependent on that of mycorrhizal fungi; a higher fungal population was correlated with higher euryarchaeotal frequency and diversity, while absence of mycorrihizal fungi was correlated with absence of euryarchaeota.[8]

Phylogeny

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)[9] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[10]

| 16S rRNA based LTP_12_2021.[11][12][13] | Dombrowski et al. 2019,[14] Jordan et al. 2017[15] and Cavalier-Smith2020.[16] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Other phylogenetic analyzes have suggested that the archaea of the clade DPANN may also belong to Euryarchaeota and that they may even be a polyphyletic group occupying different phylogenetic positions within Euryarchaeota. It is also debated whether the phylum Altiarchaeota should be classified in DPANN or Euryarchaeota.[14] A cladogram summarizing this proposal is graphed below.[15][16] The groups marked in quotes are lineages assigned to DPANN, but phylogenetically separated from the rest.

|

A third phylogeny, 53 marker proteins based GTDB 08-RS214.[17][18][19]

|

Euryarchaeota s.s. |

See also

References

- ↑ "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87 (12): 4576–9. June 1990. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMID 2112744. Bibcode: 1990PNAS...87.4576W.

- ↑ "Major New Microbial Groups Expand Diversity and Alter our Understanding of the Tree of Life". Cell 172 (6): 1181–1197. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.016. PMID 29522741.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael (2010). "Archaea". in E. Monosson; C. Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment. http://editors.eol.org/eoearth/wiki/Archaea.

- ↑ "Planktonic Euryarchaeota are a significant source of archaeal tetraether lipids in the ocean". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (27): 9858–63. July 2014. doi:10.1073/pnas.1409439111. PMID 24946804. Bibcode: 2014PNAS..111.9858L.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Whitman WB, ed (2015). "Euryarchaeota phy. nov.". Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118960608. ISBN 9781118960608.

- ↑ "Untangling genomes from metagenomes: revealing an uncultured class of marine Euryarchaeota". Science 335 (6068): 587–90. February 2012. doi:10.1126/science.1212665. PMID 22301318. Bibcode: 2012Sci...335..587I.

- ↑ "Archaea dominate the microbial community in an ecosystem with low-to-moderate temperature and extreme acidity". Microbiome 7 (1): 11. January 2019. doi:10.1186/s40168-019-0623-8. PMID 30691532.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Distribution of cren- and euryarchaeota in scots pine mycorrhizospheres and boreal forest humus". Microbial Ecology 54 (3): 406–16. October 2007. doi:10.1007/s00248-007-9232-3. PMID 17334967.

- ↑ "Euryarchaeota". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). http://www.bacterio.net/-classifphyla%20copy.html#Euryarchaeota.

- ↑ Sayers. "Euryarchaeota". Taxonomy Browser. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomy database. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Tree&id=28890&lvl=3&lin.

- ↑ "The LTP". https://imedea.uib-csic.es/mmg/ltp/#LTP.

- ↑ "LTP_all tree in newick format". https://imedea.uib-csic.es/mmg/ltp/wp-content/uploads/ltp/Tree_LTP_all_12_2021.ntree.

- ↑ "LTP_12_2021 Release Notes". https://imedea.uib-csic.es/mmg/ltp/wp-content/uploads/ltp/LTP_12_2021_release_notes.pdf.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Nina Dombrowski, Jun-Hoe Lee, Tom A Williams, Pierre Offre, Anja Spang (2019). Genomic diversity, lifestyles and evolutionary origins of DPANN archaea. Nature.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Jordan T. Bird, Brett J. Baker, Alexander J. Probst, Mircea Podar, Karen G. Lloyd (2017). Culture Independent Genomic Comparisons Reveal Environmental Adaptations for Altiarchaeales. Frontiers.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Chao, Ema E-Yung (2020). "Multidomain ribosomal protein trees and the planctobacterial origin of neomura (Eukaryotes, archaebacteria)". Protoplasma 257 (3): 621–753. doi:10.1007/s00709-019-01442-7. PMID 31900730.

- ↑ "GTDB release 08-RS214". https://gtdb.ecogenomic.org/about#4%7C.

- ↑ "ar53_r214.sp_label". https://data.gtdb.ecogenomic.org/releases/release214/214.0/auxillary_files/ar53_r214.sp_labels.tree.

- ↑ "Taxon History". https://gtdb.ecogenomic.org/taxon_history/.

- ↑ Anja Spang, Eva F. Caceres, Thijs J. G. Ettema: Genomic exploration of the diversity, ecology, and evolution of the archaeal domain of life. In: Science Volume 357 Issue 6351, eaaf3883, 11 Aug 2017, doi:10.1126/science.aaf3883

- ↑ Sometines misspelled as Theinoarchaea: Catherine Badel, Gaël Erauso, Annika L. Gomez, Ryan Catchpole, Mathieu Gonnet, Jacques Oberto, Patrick Forterre, Violette Da Cunha: The global distribution and evolutionary history of the pT26‐2 archaeal plasmid family. In: environmental microbiology. sfam 10 Sep 2019. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.14800

- ↑ NCBI: Candidatus Poseidoniia (class)

Further reading

- "The neomuran origin of archaebacteria, the negibacterial root of the universal tree and bacterial megaclassification". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 52 (Pt 1): 7–76. January 2002. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-1-7. PMID 11837318.

- "The phylogenetic relationships of three sulfur dependent archaebacteria". Systematic and Applied Microbiology 5: 97–105. 1984. doi:10.1016/S0723-2020(84)80054-5. PMID 11541975.

- "Phylum AII. Euryarchaeota phy. nov.". Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology Volume 1: The Archaea and the deeply branching and phototrophic Bacteria (2nd ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. 2001. pp. 169. ISBN 978-0-387-98771-2. https://archive.org/details/bergeysmanualofs00boon.

External links

- PubMed references for Euryarchaeota

- PubMed Central references for Euryarchaeota

- Google Scholar references for Euryarchaeota

- Comparative Analysis of Euryarchaeota Genomes (at DOE's IMG system)`1

- NCBI taxonomy page for Euryarchaeota

- Search Tree of Life taxonomy pages for Euryarchaeota

- Search Species2000 page for Euryarchaeota

- MicrobeWiki page for Euryarchaeota

Wikidata ☰ Q204219 entry

|