Deep belief network

| Machine learning and data mining |

|---|

|

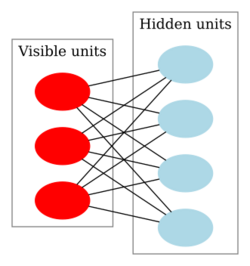

In machine learning, a deep belief network (DBN) is a generative graphical model, or alternatively a class of deep neural network, composed of multiple layers of latent variables ("hidden units"), with connections between the layers but not between units within each layer.[1]

When trained without supervision on a set of examples, a DBN can learn to probabilistically reconstruct its inputs. The layers then act as feature detectors.[1] After this learning step, a DBN can be further trained with supervision to perform classification.[2]

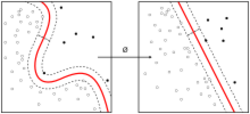

DBNs can be viewed as a composition of simple, unsupervised networks such as restricted Boltzmann machines (RBMs)[1] or autoencoders,[3] where each sub-network's hidden layer serves as the visible layer for the next. An RBM is an undirected, generative energy-based model with a "visible" input layer and a hidden layer and connections between but not within layers. This composition leads to a fast, layer-by-layer unsupervised training procedure, where contrastive divergence is applied to each sub-network in turn, starting from the "lowest" pair of layers (the lowest visible layer is a training set).

The observation[2] that DBNs can be trained greedily, one layer at a time, led to one of the first effective deep learning algorithms.[4]: 6 Overall, there are many attractive implementations and uses of DBNs in real-life applications and scenarios (e.g., electroencephalography,[5] drug discovery[6][7][8]).

Training

The training method for RBMs proposed by Geoffrey Hinton for use with training "Product of Experts" models is called contrastive divergence (CD).[9] CD provides an approximation to the maximum likelihood method that would ideally be applied for learning the weights.[10][11] In training a single RBM, weight updates are performed with gradient descent via the following equation:

where, is the probability of a visible vector, which is given by . is the partition function (used for normalizing) and is the energy function assigned to the state of the network. A lower energy indicates the network is in a more "desirable" configuration. The gradient has the simple form where represent averages with respect to distribution . The issue arises in sampling because this requires extended alternating Gibbs sampling. CD replaces this step by running alternating Gibbs sampling for steps (values of perform well). After steps, the data are sampled and that sample is used in place of . The CD procedure works as follows:[10]

- Initialize the visible units to a training vector.

- Update the hidden units in parallel given the visible units: . is the sigmoid function and is the bias of .

- Update the visible units in parallel given the hidden units: . is the bias of . This is called the "reconstruction" step.

- Re-update the hidden units in parallel given the reconstructed visible units using the same equation as in step 2.

- Perform the weight update: .

Once an RBM is trained, another RBM is "stacked" atop it, taking its input from the final trained layer. The new visible layer is initialized to a training vector, and values for the units in the already-trained layers are assigned using the current weights and biases. The new RBM is then trained with the procedure above. This whole process is repeated until the desired stopping criterion is met.[12]

Although the approximation of CD to maximum likelihood is crude (does not follow the gradient of any function), it is empirically effective.[10]

See also

- Bayesian network

- Convolutional deep belief network

- Deep learning

- Energy based model

- Stacked Restricted Boltzmann Machine

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Deep belief networks". Scholarpedia 4 (5): 5947. 2009. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.5947. Bibcode: 2009SchpJ...4.5947H.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets". Neural Computation 18 (7): 1527–54. July 2006. doi:10.1162/neco.2006.18.7.1527. PMID 16764513. http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~hinton/absps/fastnc.pdf.

- ↑ Bengio, Yoshua; Lamblin, Pascal; Popovici, Dan; Larochelle, Hugh (2007). "Greedy Layer-Wise Training of Deep Networks". NIPS. http://papers.nips.cc/paper/3048-greedy-layer-wise-training-of-deep-networks.pdf.

- ↑ Bengio, Y. (2009). "Learning Deep Architectures for AI". Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning 2: 1–127. doi:10.1561/2200000006. http://www.iro.umontreal.ca/~lisa/pointeurs/TR1312.pdf.

- ↑ "Deep Belief Networks for Electroencephalography: A Review of Recent Contributions and Future Outlooks" (in en-US). IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 22 (3): 642–652. May 2018. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2017.2727218. PMID 28715343.

- ↑ Ghasemi, Pérez-Sánchez; Mehri, Pérez-Garrido (2018). "Neural network and deep-learning algorithms used in QSAR studies: merits and drawbacks". Drug Discovery Today 23 (10): 1784–1790. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2018.06.016. PMID 29936244.

- ↑ Ghasemi, Pérez-Sánchez; Mehri, fassihi (2016). "The Role of Different Sampling Methods in Improving Biological Activity Prediction Using Deep Belief Network". Journal of Computational Chemistry 38 (10): 1–8. doi:10.1002/jcc.24671. PMID 27862046.

- ↑ "Deep Learning in Drug Discovery". Molecular Informatics 35 (1): 3–14. January 2016. doi:10.1002/minf.201501008. PMID 27491648.

- ↑ "Training Product of Experts by Minimizing Contrastive Divergence". Neural Computation 14 (8): 1771–1800. 2002. doi:10.1162/089976602760128018. PMID 12180402. http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~fritz/absps/nccd.pdf.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "A Practical Guide to Training Restricted Boltzmann Machines". Tech. Rep. UTML TR 2010-003. 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221166159.

- ↑ "Training Restricted Boltzmann Machines: An Introduction". Pattern Recognition 47 (1): 25–39. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2013.05.025. Bibcode: 2014PatRe..47...25F. http://image.diku.dk/igel/paper/TRBMAI.pdf. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- ↑ Bengio, Yoshua (2009). "Learning Deep Architectures for AI". Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning 2 (1): 1–127. doi:10.1561/2200000006. http://sanghv.com/download/soft/machine%20learning,%20artificial%20intelligence,%20mathematics%20ebooks/ML/learning%20deep%20architectures%20for%20AI%20%282009%29.pdf. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

External links

- Hinton, Geoffrey E. (2009-05-31). "Deep belief networks" (in en). Scholarpedia 4 (5): 5947. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.5947. ISSN 1941-6016. Bibcode: 2009SchpJ...4.5947H.

- "Deep Belief Networks". Deep Learning Tutorials. http://deeplearning.net/tutorial/DBN.html.

- "Deep Belief Network Example". Deeplearning4j Tutorials. http://deeplearning4j.org/deepbeliefnetwork.html.

|