Medicine:Chickenpox

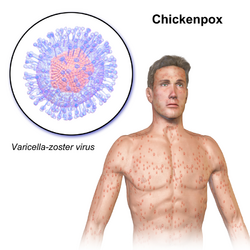

Chickenpox, also known as varicella (/ˌværɪˈsɛlə/ (![]() listen) VARR-iss-EL-ə), is a highly contagious disease caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV), a member of the herpesvirus family.[1][2][3] The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which eventually scab over.[4] It usually starts on the chest, back, and face.[4] It then spreads to the rest of the body.[4] The rash and other symptoms, such as fever, tiredness, and headaches, usually last five to seven days.[4] Complications may occasionally include pneumonia, inflammation of the brain, and bacterial skin infections.[5] The disease is usually more severe in adults than in children.[6]

listen) VARR-iss-EL-ə), is a highly contagious disease caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV), a member of the herpesvirus family.[1][2][3] The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which eventually scab over.[4] It usually starts on the chest, back, and face.[4] It then spreads to the rest of the body.[4] The rash and other symptoms, such as fever, tiredness, and headaches, usually last five to seven days.[4] Complications may occasionally include pneumonia, inflammation of the brain, and bacterial skin infections.[5] The disease is usually more severe in adults than in children.[6]

Chickenpox is an airborne disease which easily spreads via human-to-human transmission, typically through the coughs and sneezes of an infected person.[3] The incubation period is 10–21 days, after which the characteristic rash appears.[7] It may be spread from one to two days before the rash appears until all lesions have crusted over.[3] It may also spread through contact with the blisters.[3] Those with shingles may spread chickenpox to those who are not immune through contact with the blisters.[3] The disease can usually be diagnosed based on the presenting symptom;[8] however, in unusual cases it may be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of the blister fluid or scabs.[6] Testing for antibodies may be done to determine if a person is immune.[6] People usually only get chickenpox once.[3] Although reinfections by the virus occur, these reinfections usually do not cause any symptoms.[9]

Since its introduction in 1995 in the United States, the varicella vaccine has resulted in a decrease in the number of cases and complications from the disease.[10] It protects about 70–90 percent of people from disease with a greater benefit for severe disease.[6] Routine immunization of children is recommended in many countries.[11] Immunization within three days of exposure may improve outcomes in children.[12] Treatment of those infected may include calamine lotion to help with itching, keeping the fingernails short to decrease injury from scratching, and the use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) to help with fevers.[3] For those at increased risk of complications, antiviral medication such as aciclovir is recommended.[3]

Chickenpox occurs in all parts of the world.[6] In 2013, there were 140 million cases of chickenpox and shingles worldwide.[13] Before routine immunization the number of cases occurring each year was similar to the number of people born.[6] Since immunization the number of infections in the United States has decreased nearly 90%.[6] In 2015 chickenpox resulted in 6,400 deaths globally – down from 8,900 in 1990.[14][15] Death occurs in about 1 per 60,000 cases.[6] Chickenpox was not separated from smallpox until the late 19th century.[6] In 1888 its connection to shingles was determined.[6] The first documented use of the term chicken pox was in 1658.[16] Various explanations have been suggested for the use of "chicken" in the name, one being the relative mildness of the disease.[16]

Signs and symptoms

The early (prodromal) symptoms in adolescents and adults are nausea, loss of appetite, aching muscles, and headache.[17] This is followed by the characteristic rash or oral sores, malaise, and a low-grade fever that signals the presence of the disease. Oral manifestations of the disease (enanthem) not uncommonly may precede the external rash (exanthem). In children, the illness is not usually preceded by prodromal symptoms, and the first sign is the rash or the spots in the oral cavity. The rash begins as small red dots on the face, scalp, torso, upper arms, and legs; progressing over 10–12 hours to small bumps, blisters, and pustules; followed by umbilication and the formation of scabs.[18][19]

At the blister stage, intense itching is usually present. Blisters may also occur on the palms, soles, and genital area. Commonly, visible evidence of the disease develops in the oral cavity and tonsil areas in the form of small ulcers which can be painful, itchy, or both; this enanthem (internal rash) can precede the exanthem (external rash) by 1 to 3 days or can be concurrent. These symptoms of chickenpox appear 10 to 21 days after exposure to a contagious person. Adults may have a more widespread rash and longer fever, and they are more likely to experience complications, such as varicella pneumonia.[18]

Because watery nasal discharge containing live virus usually precedes both exanthem (external rash) and enanthem (oral ulcers) by one to two days, the infected person becomes contagious one to two days before recognition of the disease. Contagiousness persists until all vesicular lesions have become dry crusts (scabs), which usually entails four or five days, by which time nasal shedding of live virus ceases.[20] The condition usually resolves by itself within a week or two.[21] The rash may, however, last for up to one month.[22]

Chickenpox is rarely fatal, although it is generally more severe in adult men than in women or children. Non-immune pregnant women and those with a suppressed immune system are at highest risk of serious complications. Arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) associated with chickenpox in the previous year accounts for nearly one-third of childhood AIS.[23] The most common late complication of chickenpox is shingles (herpes zoster), caused by reactivation of the varicella zoster virus decades after the initial, often childhood, chickenpox infection.[22]

-

The back of a 30-year-old male after five days of the rash

-

A 3-year-old girl with a chickenpox rash on her torso

-

Lower leg of a child with chickenpox

-

A child with chickenpox

-

A child with chickenpox on her face.

-

A child with chickenpox

-

Chickenpox blister closeup, day 7 after start of fever

Pregnancy and neonates

During pregnancy the dangers to the fetus associated with a primary VZV infection are greater in the first six months. In the third trimester, the mother is more likely to have severe symptoms.[24] For pregnant women, antibodies produced as a result of immunization or previous infection are transferred via the placenta to the fetus.[25] Varicella infection in pregnant women could lead to spread via the placenta and infection of the fetus. If infection occurs during the first 28 weeks of gestation, this can lead to fetal varicella syndrome (also known as congenital varicella syndrome).[26] Effects on the fetus can range in severity from underdeveloped toes and fingers to severe anal and bladder malformation.[22] Possible problems include:

- Damage to the brain: encephalitis,[27] microcephaly, hydrocephaly,[28] aplasia of brain

- Damage to the eye: optic stalk, optic cup, and lens vesicles, microphthalmia, cataracts, chorioretinitis, optic atrophy

- Other neurological disorder: damage to cervical and lumbosacral spinal cord, motor/sensory deficits, absent deep tendon reflexes, anisocoria/Horner's syndrome

- Damage to body: hypoplasia of upper/lower extremities, anal and bladder sphincter dysfunction

- Skin disorders: (cicatricial) skin lesions, hypopigmentation

Infection late in gestation or immediately following birth is referred to as "neonatal varicella".[29] Maternal infection is associated with premature delivery. The risk of the baby developing the disease is greatest following exposure to infection in the period 7 days before delivery and up to 8 days following the birth. The baby may also be exposed to the virus via infectious siblings or other contacts, but this is of less concern if the mother is immune. Newborns who develop symptoms are at a high risk of pneumonia and other serious complications of the disease.[30]

Pathophysiology

Exposure to VZV in a healthy child initiates the production of host immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), and immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies; IgG antibodies persist for life and confer immunity. Cell-mediated immune responses are also important in limiting the scope and the duration of primary varicella infection. After primary infection, VZV is hypothesized to spread from mucosal and epidermal lesions to local sensory nerves. VZV then remains latent in the dorsal ganglion cells of the sensory nerves. Reactivation of VZV results in the clinically distinct syndrome of herpes zoster (i.e., shingles), postherpetic neuralgia,[31] and sometimes Ramsay Hunt syndrome type II.[32] Varicella zoster can affect the arteries in the neck and head, producing stroke, either during childhood, or after a latency period of many years.[33]

Shingles

After a chickenpox infection, the virus remains dormant in the body's nerve tissues for about 50 years. However, this does not mean that VZV cannot be contracted later in life. The immune system usually keeps the virus at bay, but it can still manifest itself at any given age causing a different form of the viral infection called shingles (also known as herpes zoster).[34] Since the efficacy of the human immune system decreases with age, the United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) suggests that every adult over the age of 50 years get the herpes zoster vaccine.[35]

Shingles affects one in five adults infected with chickenpox as children, especially those who are immune-suppressed, particularly from cancer, HIV, or other conditions. Stress can bring on shingles as well, although scientists are still researching the connection.[36] Adults over the age of 60 who had chickenpox but not shingles are the most prone age demographic.[37]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of chickenpox is primarily based on the signs and symptoms, with typical early symptoms followed by a characteristic rash. Confirmation of the diagnosis is by examination of the fluid within the vesicles of the rash, or by testing blood for evidence of an acute immunologic response.[38]

Vesicular fluid can be examined with a Tzanck smear, or by testing for direct fluorescent antibody. The fluid can also be "cultured", whereby attempts are made to grow the virus from a fluid sample. Blood tests can be used to identify a response to acute infection (IgM) or previous infection and subsequent immunity (IgG).[39]

Prenatal diagnosis of fetal varicella infection can be performed using ultrasound, though a delay of 5 weeks following primary maternal infection is advised. A PCR (DNA) test of the mother's amniotic fluid can also be performed, though the risk of spontaneous abortion due to the amniocentesis procedure is higher than the risk of the baby's developing fetal varicella syndrome.[30]

Prevention

Hygiene measures

The spread of chickenpox can be prevented by isolating affected individuals. Contagion is by exposure to respiratory droplets, or direct contact with lesions, within a period lasting from three days before the onset of the rash, to four days after the onset of the rash.[40] The chickenpox virus is susceptible to disinfectants, notably chlorine bleach (i.e., sodium hypochlorite). Like all enveloped viruses, it is sensitive to drying, heat and detergents.[22]

Vaccine

Chickenpox can be prevented by vaccination.[7] The side effects are usually mild, such as some pain or swelling at the injection site.[7]

A live attenuated varicella vaccine, the Oka strain, was developed by Michiaki Takahashi and his colleagues in Japan in the early 1970s.[41] In 1995, Merck & Co. licensed the "Oka" strain of the varicella virus in the United States, and Maurice Hilleman's team at Merck invented a varicella vaccine in the same year.[42][43][44]

The varicella vaccine is recommended in many countries.[11] Some countries require the varicella vaccination or an exemption before entering elementary school. A second dose is recommended five years after the initial immunization.[45] A vaccinated person is likely to have a milder case of chickenpox if they become infected.[46] Immunization within three days following household contact reduces infection rates and severity in children.[12] Being exposed to chickenpox as an adult (for example, through contact with infected children) may boost immunity to shingles. Therefore, it was thought that when the majority of children were vaccinated against chickenpox, adults might lose this natural boost, so immunity would drop and more shingles cases would occur.[47] On the other hand, current observations suggest that exposure to children with varicella is not a critical factor in the maintenance of immunity. Multiple subclinical reactivations of varicella-zoster virus may occur spontaneously and, despite not causing clinical disease, may still provide an endogenous boost to immunity against zoster.[48]

The vaccine is part of the routine immunization schedule in the US.[49] Some European countries include it as part of universal vaccinations in children,[50] but not all countries provide the vaccine.[11] In the UK as of 2014, the vaccine is only recommended in people who are particularly vulnerable to chickenpox. This is to keep the virus in circulation, thereby exposing the population to the virus at an early age when it is less harmful, and to reduce the occurrence of shingles through repeated exposure to the virus later in life.[51] In November 2023, the UK Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation recommended all children be given the vaccine at ages 12 months and 18 months; however, this has not yet been implemented. In populations that have not been immunized or if immunity is questionable, a clinician may order an enzyme immunoassay. An immunoassay measures the levels of antibodies against the virus that give immunity to a person. If the levels of antibodies are low (low titer) or questionable, reimmunization may be done.[52]

Treatment

Treatment mainly consists of easing the symptoms. As a protective measure, people are usually required to stay at home while they are infectious to avoid spreading the disease to others. Cutting the fingernails short or wearing gloves may prevent scratching and minimize the risk of secondary infections.[53]

Although there have been no formal clinical studies evaluating the effectiveness of topical application of calamine lotion (a topical barrier preparation containing zinc oxide, and one of the most commonly used interventions), it has an excellent safety profile.[54] Maintaining good hygiene and daily cleaning of skin with warm water can help to avoid secondary bacterial infection;[55] scratching may increase the risk of secondary infection.[56]

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) but not aspirin may be used to reduce fever. Aspirin use by someone with chickenpox may cause serious, sometimes fatal disease of the liver and brain, Reye syndrome. People at risk of developing severe complications who have had significant exposure to the virus may be given intra-muscular varicella zoster immune globulin (VZIG), a preparation containing high titres of antibodies to varicella zoster virus, to ward off the disease.[57][58]

Antivirals are sometimes used.[59][60]

Children

If aciclovir by mouth is started within 24 hours of rash onset, it decreases symptoms by one day but does not affect complication rates.[61][62] Use of aciclovir, therefore, is not currently recommended for individuals with normal immune function. Children younger than 12 years old and older than one month are not meant to receive antiviral drugs unless they have another medical condition that puts them at risk of developing complications.[63]

Treatment of chickenpox in children is aimed at symptoms while the immune system deals with the virus. With children younger than 12 years, cutting fingernails and keeping them clean is an important part of treatment as they are more likely to scratch their blisters more deeply than adults.[64]

Aspirin is highly contraindicated in children younger than 16 years, as it has been related to Reye syndrome.[65]

Adults

Infection in otherwise healthy adults tends to be more severe.[66] Treatment with antiviral drugs (e.g. aciclovir or valaciclovir) is generally advised, as long as it is started within 24–48 hours from rash onset.[63] Remedies to ease the symptoms of chickenpox in adults are generally the same as those used for children. Adults are more often prescribed antiviral medication, as it is effective in reducing the severity of the condition and the likelihood of developing complications. Adults are advised to increase water intake to reduce dehydration and relieve headaches. Painkillers such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) are recommended, as they are effective in relieving itching and other symptoms such as fever or pain. Antihistamines relieve itching and may be used in cases where the itching prevents sleep because they also act as a sedative. As with children, antiviral medication is considered more useful for those adults who are more prone to develop complications. These include pregnant women or people who have a weakened immune system.[67]

Prognosis

The duration of the visible blistering caused by varicella zoster virus varies in children usually from four to seven days, and the appearance of new blisters begins to subside after the fifth day. Chickenpox infection is milder in young children, and symptomatic treatment with sodium bicarbonate baths or antihistamine medication may ease itching.

In adults, the disease is more severe,[68] though the incidence is much less common. Infection in adults is associated with greater morbidity and mortality due to pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia),[69] bronchitis (either viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis),[69] hepatitis,[70] and encephalitis.[71] In particular, up to 10% of pregnant women with chickenpox develop pneumonia, the severity of which increases with onset later in gestation. In England and Wales, 75% of deaths due to chickenpox are in adults.[30] Inflammation of the brain, encephalitis, can occur in immunocompromised individuals, although the risk is higher with herpes zoster.[72] Necrotizing fasciitis is also a rare complication.[73]

Varicella can be lethal to individuals with impaired immunity. The number of people in this high-risk group has increased, due to the HIV epidemic and the increased use of immunosuppressive therapies.[74] Varicella is a particular problem in hospitals when there are patients with immune systems weakened by drugs (e.g., high-dose steroids) or HIV.[75]

Secondary bacterial infection of skin lesions, manifesting as impetigo, cellulitis, and erysipelas, is the most common complication in healthy children. Disseminated primary varicella infection usually seen in the immunocompromised may have high morbidity. Ninety percent of cases of varicella pneumonia occur in the adult population. Rarer complications of disseminated chickenpox include myocarditis, hepatitis, and glomerulonephritis.[76]

Hemorrhagic complications are more common in the immunocompromised or immunosuppressed populations, although healthy children and adults have been affected. Five major clinical syndromes have been described: febrile purpura, malignant chickenpox with purpura, postinfectious purpura, purpura fulminans, and anaphylactoid purpura. These syndromes have variable courses, with febrile purpura being the most benign of the syndromes and having an uncomplicated outcome. In contrast, malignant chickenpox with purpura is a grave clinical condition that has a mortality rate of greater than 70%. The cause of these hemorrhagic chickenpox syndromes is not known.[76]

Epidemiology

Primary varicella occurs in all countries worldwide. In 2015 chickenpox resulted in 6,400 deaths globally – down from 8,900 in 1990.[14] There were 7,000 deaths in 2013.[15] Varicella is highly transmissible, with an infection rate of 90% in close contacts.[77]

In temperate countries, chickenpox is primarily a disease of children, with most cases occurring during the winter and spring, most likely due to school contact. In such countries it is one of the classic diseases of childhood, with most cases occurring in children up to age 15;[78] most people become infected before adulthood, and 10% of young adults remain susceptible.

In the United States, a temperate country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) do not require state health departments to report infections of chickenpox, and only 31 states volunteered this information as of 2013[update].[79] A 2013 study conducted by the social media disease surveillance tool called Sickweather used anecdotal reports of chickenpox infections on social media systems Facebook and Twitter to measure and rank states with the most infections per capita, with Maryland, Tennessee and Illinois in the top three.[80]

In the tropics, chickenpox often occurs in older people and may cause more serious disease.[81] In adults, the pockmarks are darker and the scars more prominent than in children.[82]

Society and culture

Etymology

How the term chickenpox originated is not clear but it may be due to it being a relatively mild disease.[16] It has been said to be derived from chickpeas, based on resemblance of the vesicles to chickpeas,[16][83][84] or to come from the rash resembling chicken pecks.[84] Other suggestions include the designation chicken for a child (i.e., literally 'child pox'), a corruption of itching-pox,[83][85] or the idea that the disease may have originated in chickens.[86] Samuel Johnson explained the designation as "from its being of no very great danger".[87]

Intentional exposure

Because chickenpox is usually more severe in adults than it is in children, some parents deliberately expose their children to the virus, for example by taking them to "chickenpox parties".[88] Doctors say that children are safer getting the vaccine, which is a weakened form of the virus, than getting the disease, which can be fatal or lead to shingles later in life.[88][89][90] Repeated exposure to chickenpox may protect against zoster.[91]

Other animals

Humans are the only known species that the disease affects naturally.[6] However, chickenpox has been caused in animals, including chimpanzees[92] and gorillas.[93]

Research

Sorivudine, a nucleoside analog, has been reported to be effective in the treatment of primary varicella in healthy adults (case reports only), but large-scale clinical trials are still needed to demonstrate its efficacy.[94] There was speculation in 2005 that continuous dosing of aciclovir by mouth for a period of time could eradicate VZV from the host, although further trials were required to discern whether eradication was actually viable.[95]

See also

References

- ↑ "Chickenpox (Varicella) Overview". 16 November 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/about/overview.html.

- ↑ "Varicella" (in en). https://www.who.int/teams/health-product-policy-and-standards/standards-and-specifications/vaccine-standardization/varicella.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 "Chickenpox (Varicella) Prevention & Treatment". 16 November 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/about/prevention-treatment.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Chickenpox (Varicella) Signs & Symptoms". 16 November 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/about/symptoms.html.

- ↑ "Chickenpox (Varicella) Complications". 16 November 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/index.html.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 Atkinson, William (2011). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (12 ed.). Public Health Foundation. pp. 301–323. ISBN 978-0-9832631-3-5. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/varicella.html. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Chickenpox (Varicella) For Healthcare Professionals". 31 December 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/hcp/index.html.

- ↑ "Chickenpox (Varicella) Interpreting Laboratory Tests". 19 June 2012. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/hcp/lab-tests.html.

- ↑ "VZV molecular epidemiology". Varicella-zoster Virus. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 342. 2010. pp. 15–42. doi:10.1007/82_2010_9. ISBN 978-3-642-12727-4.

- ↑ "Routine vaccination against chickenpox?". Drug Ther Bull 50 (4): 42–45. 2012. doi:10.1136/dtb.2012.04.0098. PMID 22495050.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Flatt, A; Breuer, J (September 2012). "Varicella vaccines.". British Medical Bulletin 103 (1): 115–127. doi:10.1093/bmb/lds019. PMID 22859715.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Macartney, K; Heywood, A; McIntyre, P (23 June 2014). "Vaccines for post-exposure prophylaxis against varicella (chickenpox) in children and adults.". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 6 (6). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001833.pub3. PMID 24954057.

- ↑ "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet 386 (9995): 743–800. 22 August 2015. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMID 26063472.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.". Lancet 388 (10053): 1459–1544. 8 October 2016. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet 385 (9963): 117–171. 17 December 2014. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "chickenpox, n.". December 2014. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/31556?redirectedFrom=Chickenpox.

- ↑ "Chickenpox". Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chickenpox/symptoms-causes/syc-20351282.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Anthony J Papadopoulos. "Chickenpox Clinical Presentation". in Dirk M Elston. Medscape Reference. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1131785.

- ↑ "Symptoms of Chickenpox". Chickenpox. NHS Choices. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Chickenpox/Pages/Symptoms.aspx.

- ↑ "Chickenpox (Varicella): Clinical Overview". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 April 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/hcp/clinical-overview.html.

- ↑ "Chickenpox (varicella)". http://www.netdoctor.co.uk/diseases/facts/chickenpox.htm.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 "Chickenpox - Symptoms and causes" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chickenpox/symptoms-causes/syc-20351282.

- ↑ "Chickenpox and stroke in childhood: a study of frequency and causation". Stroke 32 (6): 1257–1262. June 2001. doi:10.1161/01.STR.32.6.1257. PMID 11387484.

- ↑ "The management of varicella-zoster virus exposure and infection in pregnancy and the newborn period. Australasian Subgroup in Paediatric Infectious Diseases of the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases.". The Medical Journal of Australia 174 (6): 288–292. 19 March 2001. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143273.x. PMID 11297117. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2001/174/6/management-varicella-zoster-virus-exposure-and-infection-pregnancy-and-newborn.

- ↑ Brannon, Heather (22 July 2007). "Chickenpox in Pregnancy". Dermatology. About.com. http://dermatology.about.com/cs/pregnancy/a/chickenpreg.htm.

- ↑ "Chronic varicella-zoster skin infection complicating the congenital varicella syndrome". Pediatr Dermatol 24 (4): 429–432. 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00471.x. PMID 17845179.

- ↑ "Acute retinal necrosis as a novel complication of chickenpox in adults". Br J Ophthalmol 74 (7): 443–444. July 1990. doi:10.1136/bjo.74.7.443. PMID 2378860.

- ↑ "Severe hydrocephalus associated with congenital varicella syndrome". Canadian Medical Association Journal 168 (5): 561–563. 2003. PMID 12615748.

- ↑ "Neonatal varicella". J Perinatol 21 (8): 545–549. December 2001. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7210599. PMID 11774017.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (September 2007). "Chickenpox in Pregnancy". http://www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/uploaded-files/GT13ChickenpoxinPregnancy2007.pdf.

- ↑ "Predictive Factors for Postherpetic Neuralgia Using Ordered Logistic Regression Analysis". The Clinical Journal of Pain 28 (8): 712–714. 2012. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318243ee01. PMID 22209800.

- ↑ "Ramsay-Hunt syndrome associated to unilateral recurrential paralysis". Anales Otorrinolaringologicos Ibero-americanos 33 (5): 489–494. 2006. PMID 17091862.

- ↑ "The varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: clinical, CSF, imaging, and virologic features.". Neurology 70 (11): 853–860. March 2008. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000304747.38502.e8. PMID 18332343.

- ↑ "Chickenpox". NHS Choices. UK Department of Health. 19 April 2012. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/chickenpox/Pages/Introduction.aspx.

- ↑ "Shingles Vaccine". http://www.webmd.com/skin-problems-and-treatments/shingles/shingles-vaccine.

- ↑ "An Overview of Shingles". http://www.webmd.com/skin-problems-and-treatments/shingles/shingles-skin.

- ↑ "Shingles". PubMed Health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001861/.

- ↑ Ayoade, Folusakin; Kumar, Sandeep (2020), "Varicella Zoster (Chickenpox)", StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing), PMID 28846365, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448191/, retrieved 21 October 2020

- ↑ Pincus, Matthew R.; McPherson, Richard A.; Henry, John Bernard (2007). "Ch. 54". Henry's clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods (21st ed.). Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-0287-1.

- ↑ Murray, Patrick R.; Rosenthal, Ken S.; Pfaller, Michael A. (2005). Medical Microbiology (5th ed.). Elsevier Mosby. p. 551. ISBN 978-0-323-03303-9.

- ↑ Gershon, Anne A. (2007), Arvin, Ann; Campadelli-Fiume, Gabriella; Mocarski, Edward et al., eds., "Varicella-zoster vaccine", Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), ISBN 978-0-521-82714-0, PMID 21348127, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47446/, retrieved 6 February 2021

- ↑ Tulchinsky, Theodore H. (2018). "Maurice Hilleman: Creator of Vaccines That Changed the World". Case Studies in Public Health: 443–470. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804571-8.00003-2. ISBN 978-0-12-804571-8.

- ↑ "Chickenpox (Varicella) | History of Vaccines" (in en). https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/articles/chickenpox-varicella.

- ↑ "Maurice Ralph Hilleman (1919–2005) | The Embryo Project Encyclopedia". https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/maurice-ralph-hilleman-1919-2005.

- ↑ "Loss of vaccine-induced immunity to varicella over time". N Engl J Med 356 (11): 1121–1129. 2007. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa064040. PMID 17360990.

- ↑ "Chickenpox (varicella) vaccination". NHS Choices. UK Department of Health. 19 April 2012. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/varicella-vaccine/pages/introduction.aspx.

- ↑ "Chickenpox vaccine FAQs". 23 January 2019. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/chickenpox-vaccine-questions-answers/.

- ↑ "Live Attenuated Varicella Vaccine: Prevention of Varicella and of Zoster". 30 September 2021. https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/224/Supplement_4/S387/6378094/.

- ↑ "Child, Adolescent & "Catch-up" Immunization Schedules". Immunization Schedules. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 March 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html.

- ↑ Carrillo-Santisteve, P; Lopalco, PL (May 2014). "Varicella vaccination: a laboured take-off.". Clinical Microbiology and Infection 20 (Suppl 5): 86–91. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12580. PMID 24494784.

- ↑ "Why aren't children in the UK vaccinated against chickenpox?". UK National Health Service. 26 June 2018. https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/childrens-health/why-are-children-in-the-uk-not-vaccinated-against-chickenpox/.

- ↑ Leeuwen, Anne (2015). Davis's comprehensive handbook of laboratory & diagnostic tests with nursing implications. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. p. 1579. ISBN 978-0-8036-4405-2.

- ↑ CDC (28 April 2021). "Chickenpox Prevention and Treatment" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/about/prevention-treatment.html.

- ↑ "Does the use of calamine or antihistamine provide symptomatic relief from pruritus in children with varicella zoster infection?". Arch. Dis. Child. 91 (12): 1035–1036. 2006. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.105114. PMID 17119083.

- ↑ Domino, Frank J. (2007). The 5-Minute Clinical Consult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7817-6334-9.

- ↑ Brannon, Heather (21 May 2008). Chicken Pox Treatments . About.com.

- ↑ "JAMA patient page. Chickenpox". JAMA 291 (7): 906. February 2004. doi:10.1001/jama.291.7.906. PMID 14970070.

- ↑ Naus M (15 October 2006). "Varizig™ as the Varicella Zoster Immune Globulin for the Prevention of Varicella in At-Risk Patients". Canada Communicable Disease Report 32 (ACS-8). http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/ccdr-rmtc/06vol32/acs-08/index-eng.php.

- ↑ Huff JC (January 1988). "Antiviral treatment in chickenpox and herpes zoster.". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 18 (1 Pt 2): 204–206. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(88)70029-8. PMID 3339143.

- ↑ Gnann, John W. Jr. (2007). "Chapter 65Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections". in Arvin, Ann. Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82714-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47401/. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ↑ Kay, A. B. (2001). "Allergy and allergic diseases. First of two parts". The New England Journal of Medicine 344 (1): 30–37. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101043440106. PMID 11136958.

- ↑ Kay, A. B. (2001). "Allergy and allergic diseases. Second of two parts". The New England Journal of Medicine 344 (2): 109–113. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101113440206. PMID 11150362.

- ↑ "Chickenpox in Children Under 12". http://www.patient.info/health/Chickenpox-in-Children-Under-12.htm.

- ↑ "Reye's Syndrome-Topic Overview". http://children.webmd.com/tc/reyes-syndrome-topic-overview.

- ↑ "Chickenpox in adults – clinical management". The Journal of Infection 57 (2): 95–102. August 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.004. PMID 18555533.

- ↑ "What is chickenpox?". http://www.patient.info/health/Chickenpox-in-Adults-and-Teenagers.htm.

- ↑ "Primary Varicella in Adults: Pneumonia, Pregnancy, and Hospital Admissions". Annals of Emergency Medicine 28 (2): 165–169. August 1996. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(96)70057-4. PMID 8759580.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Varicella pneumonia in adults". Eur. Respir. J. 21 (5): 886–891. May 2003. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00103202. PMID 12765439.

- ↑ Anderson, D.R.; Schwartz, J.; Hunter, N.J.; Cottrill, C.; Bissaccia, E.; Klainer, A.S. (1994). "Varicella Hepatitis: A Fatal Case in a Previously Healthy, Immunocompetent Adult". Archives of Internal Medicine 154 (18): 2101–2106. doi:10.1001/archinte.1994.00420180111013. PMID 8092915.

- ↑ "Chickenpox: presentation and complications in adults". Journal of Pakistan Medical Association 59 (12): 828–831. December 2009. PMID 20201174. http://www.jpma.org.pk/full_article_text.php?article_id=1873. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Definition of Chickenpox". MedicineNet.com. http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=2702.

- ↑ "Is Necrotizing Fasciitis a complication of Chickenpox of Cutaneous Vasculitis?". atmedstu.com. http://www.atmedstu.com/exam%20plus/Is%20Necrotizing%20Fasciitis%20a%20complication%20of%20Chickenpox%20or%20of%20Cutaneous%20Vasculitis.php.

- ↑ "Risk of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF-alpha agents". JAMA 301 (7): 737–744. February 2009. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.146. PMID 19224750.

- ↑ Weller TH (1997). "Varicella-herpes zoster virus". Viral Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control. Plenum Press. pp. 865–892. ISBN 978-0-306-44855-3.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Chicken Pox Complications

- ↑ CDC (11 August 2021). "Chickenpox for HCPs" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/chickenpox/hcp/index.html.

- ↑ Di Pietrantonj, Carlo; Rivetti, Alessandro; Marchione, Pasquale; Debalini, Maria Grazia; Demicheli, Vittorio (22 November 2021). "Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021 (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 34806766.

- ↑ "Georgia ranks 10th for social media admissions of chickenpox". http://onlineathens.com/health/2013-06-13/georgia-ranks-10th-social-media-admissions-chickenpox.

- ↑ "Chickenpox in the USA". http://www.sickweather.com/blog/post_061213.php.

- ↑ Wharton M (1996). "The epidemiology of varicella-zoster virus infections". Infect Dis Clin North Am 10 (3): 571–581. doi:10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70313-5. PMID 8856352. https://zenodo.org/record/1260109. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ↑ "Epidemiology of Varicella Zoster Virus Infection, Epidemiology of VZV Infection, Epidemiology of Chicken Pox, Epidemiology of Shingles". http://virology-online.com/viruses/VZV3.htm.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Belshe, Robert B. (1984). Textbook of human virology (2nd ed.). Littleton, MA: PSG. p. 829. ISBN 978-0-88416-458-6.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Teri Shors (2011). "Herpesviruses: Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV)". Understanding Viruses (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-7637-8553-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=Uk8xP5LRHr4C&pg=PA459.

- ↑ Pattison, John; Zuckerman, Arie J.; Banatvala, J.E. (1994). Principles and practice of clinical virology (3rd ed.). Wiley. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-471-93106-5.

- ↑ Chicken-pox is recorded in Oxford English Dictionary 2nd ed. since 1684; the OED records several suggested etymologies

- ↑ Johnson, Samuel (1839). Dictionary of the English language. London: Williamson. p. 195.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Charles, Shamard (22 March 2019). "Doctors say Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin is wrong about 'chickenpox on purpose'". https://www.nbcnews.com/health/kids-health/doctors-say-kentucky-gov-matt-bevin-wrong-about-chickenpox-purpose-n986091. "Chickenpox parties were once a popular way for parents to expose their children to the virus so they would get sick, recover and build up immunity to the disease. ... Most doctors believe that deliberately infecting a child with the full-blown virus is a bad idea. While chickenpox is mild for most children, it can be a dangerous virus for others – and there's no way to know which child will have a serious case, experts say."

- ↑ "Chicken Pox parties do more harm than good, says doctor". KSLA News 12 Shreveport, Louisiana News Weather & Sports. http://www.ksla.com/story/16317324/chicken-pox-parties-do-more-harm-than-good-says-doctor.

- ↑ Committee to Review Adverse Effects of Vaccines; Institute of, Medicine; Stratton, K.; Ford, A.; Rusch, E.; Clayton, E. W. (2011). Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality.. doi:10.17226/13164. ISBN 978-0-309-21435-3.

- ↑ Ogunjimi, B; Van Damme, P; Beutels, P (2013). "Herpes Zoster Risk Reduction through Exposure to Chickenpox Patients: A Systematic Multidisciplinary Review.". PLOS ONE 8 (6). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066485. PMID 23805224. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...866485O.

- ↑ "Varicella in Chimpanzees". Journal of Medical Virology 50 (4): 289–292. December 1996. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199612)50:4<289::AID-JMV2>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 8950684. https://zenodo.org/record/1235476. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ↑ "Varicella in a gorilla". Journal of Medical Virology 23 (4): 317–322. December 1987. doi:10.1002/jmv.1890230403. PMID 2826674.

- ↑ Chickenpox Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Treatment in Healthy Children, Treatment in Immunocompetent Adults. 3 June 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1131785-treatment#d10. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ↑ Klassen, TP; Hartling, L. (2005). "Acyclovir for treating varicella in otherwise healthy children and adolescents". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011 (4). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002980.pub3. PMID 16235308.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chickenpox. |

- Prevention of Varicella: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 1996

- Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections, 2007

- Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: Varicella, US CDC's "Pink Book"

- Chickenpox at MedlinePlus

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|