Biology:Coxsackievirus

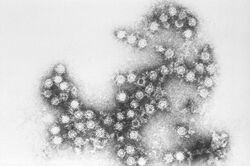

Coxsackieviruses are a few related enteroviruses that belong to the Picornaviridae family of nonenveloped, linear, positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses, as well as its genus Enterovirus, which also includes poliovirus and echovirus. Enteroviruses are among the most common and important human pathogens, and ordinarily its members are transmitted by the fecal–oral route. Coxsackieviruses share many characteristics with poliovirus. With control of poliovirus infections in much of the world, more attention has been focused on understanding the nonpolio enteroviruses such as coxsackievirus.

Coxsackieviruses are among the leading causes of aseptic meningitis (the other usual suspects being echovirus and mumps virus).

The entry of coxsackievirus into cells, especially endothelial cells, is mediated by coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor.

Groups

Coxsackieviruses are divided into group A and group B viruses based on early observations of their pathogenicity in neonatal mice.[1] Group A coxsackieviruses were noted to cause a flaccid paralysis (which was caused by generalized myositis) while group B coxsackieviruses were noted to cause a spastic paralysis (due to focal muscle injury and degeneration of neuronal tissue). At least 23 serotypes (1–22, 24) of group A and six serotypes (1–6) of group B are recognized.

A

In general, group A coxsackieviruses tend to infect the skin and mucous membranes, causing herpangina; acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis; and hand, foot, and mouth disease.[2]

Both group A and group B coxsackieviruses can cause nonspecific febrile illnesses, rashes, upper respiratory tract disease, and aseptic meningitis.

The basic reproduction number (R0) for Coxsackievirus A16 (Cox A16) was estimated to a median of 2.50 with an interquartile range of 1.96 to 3.67.[3]

B

Group B coxsackieviruses tend to infect the heart, pleura, pancreas, and liver, causing pleurodynia, myocarditis, pericarditis, and hepatitis (inflammation of the liver not related to the hepatotropic viruses). Coxsackie B infection of the heart can lead to pericardial effusion.

The development of insulin-dependent diabetes has recently been associated with recent enteroviral infection, particularly coxsackievirus B pancreatitis. This relationship is currently being studied further.

Sjögren syndrome is also being studied in connection with coxsackievirus, (As of January 2010).[4]

Taxonomy

There were 29 species of coxsackieviruses until 1999, when two of them were abolished and the rest merged into other species.[5]

| Former name | Current name[5] |

|---|---|

| Human coxsackievirus A1 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A2 | Enterovirus A[7] |

| Human coxsackievirus A3 | Enterovirus A[7] |

| Human coxsackievirus A4 | abolished[8] |

| Human coxsackievirus A5 | Enterovirus A[7] |

| Human coxsackievirus A6 | abolished[9] |

| Human coxsackievirus A7 | Enterovirus A[7] |

| Human coxsackievirus A8 | Enterovirus A[7] |

| Human coxsackievirus A9 | Enterovirus B[10] |

| Human coxsackievirus A10 | Enterovirus A[7] |

| Human coxsackievirus A11 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A12 | Enterovirus A[7] |

| Human coxsackievirus A13 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A14 | Enterovirus A[7] |

| Human coxsackievirus A15 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A16 | Enterovirus A[7] |

| Human coxsackievirus A17 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A18 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A19 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A20 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A21 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A22 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus A24 | Enterovirus C[6] |

| Human coxsackievirus B1 | Enterovirus B[10] |

| Human coxsackievirus B2 | Enterovirus B[10] |

| Human coxsackievirus B3 | Enterovirus B[10] |

| Human coxsackievirus B4 | Enterovirus B[10] |

| Human coxsackievirus B5 | Enterovirus B[10] |

| Human coxsackievirus B6 | Enterovirus B[10] |

History

The coxsackieviruses were discovered in 1948–49 by Gilbert Dalldorf, a scientist working at the New York State Department of Health in Albany, New York.

Dalldorf, in collaboration with Grace Sickles,[11][12] had been searching for a cure for poliomyelitis. Earlier work Dalldorf had done in monkeys suggested that fluid collected from a nonpolio virus preparation could protect against the crippling effects of polio. Using newborn mice as a vehicle, Dalldorf attempted to isolate such protective viruses from the feces of polio patients. In carrying out these experiments, he discovered viruses that often mimicked mild or nonparalytic polio. The virus family he discovered was eventually given the name Coxsackie, from Coxsackie, New York, a small town on the Hudson River where Dalldorf had obtained the first fecal specimens.[13]

Dalldorf also collaborated with Gifford on many early papers.[14][15][16][17]

The coxsackieviruses subsequently were found to cause a variety of infections, including epidemic pleurodynia (Bornholm disease), and were subdivided into groups A and B based on their pathology in newborn mice. (Coxsackie A virus causes paralysis and death of the mice, with extensive skeletal muscle necrosis; Coxsackie B causes less severe infection in the mice, but with damage to more organ systems, such as heart, brain, liver, pancreas, and skeletal muscles.)

The use of suckling mice was not Dalldorf's idea but was brought to his attention in a paper written by Danish scientists Orskov and Andersen in 1947, who were using such mice to study a mouse virus. The discovery of the coxsackieviruses stimulated many virologists to use this system, and ultimately resulted in the isolation of a large number of so-called "enteric" viruses from the gastrointestinal tract that were unrelated to poliovirus, and some of which were oncogenic (cancer-causing).

The discovery of the coxsackieviruses yielded further evidence that viruses can sometimes interfere with each other's growth and replication within a host animal. Other researchers found this interference can be mediated by a substance produced by the host animal, a protein now known as interferon. Interferon has since become prominent in the treatment of a variety of cancers and infectious diseases.

In 2007, an outbreak of coxsackievirus occurred in eastern China. It has been reported that 22 children died. More than 800 people were affected, with 200 children hospitalized.[18]

Cavatak, a wild-type Coxsackievirus A21, is being used in human clinical trials as an oncolytic virus. SCAR-Fc (Soluble Receptor Analogue) is an experimental prophylactic treatment against coxsackievirus B3 (CVB) infections.[19]

References

- ↑ Pedro-Pons, Agustín (1968) (in es). Patología y Clínica Médicas. 6 (3rd ed.). Barcelona: Salvat. p. 598. ISBN 978-84-345-1106-4.

- ↑ Seitsonen, Jani; Shakeel, Shabih; Susi, Petri; Pandurangan, Arun P.; Sinkovits, Robert S.; Hyvönen, Heini; Laurinmäki, Pasi; Ylä-Pelto, Jani et al. (2012). "Structural analysis of coxsackievirus A7 reveals conformational changes associated with uncoating". Journal of Virology 86 (13): 7207–7215. doi:10.1128/JVI.06425-11. PMID 22514349.

- ↑ "Estimation of the basic reproduction number of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16 in hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreaks". Pediatr Infect Dis J 30 (8): 675–9. Aug 2011. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3182116e95. PMID 21326133.

- ↑ Triantafyllopoulou, Antigoni et al. (2004). "Evidence for Coxsackievirus Infection in Primary Sjogren's Syndrome". Arthritis & Rheumatism 50 (9): 2897–2902. doi:10.1002/art.20463. PMID 15457458.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 ICTV 7th Report van Regenmortel, M.H.V., Fauquet, C.M., Bishop, D.H.L., Carstens, E.B., Estes, M.K., Lemon, S.M., Maniloff, J., Mayo, M.A., McGeoch, D.J., Pringle, C.R. and Wickner, R.B. (2000). Virus taxonomy. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego. 1162 pp. https://ictv.global/ictv/proposals/ICTV%207th%20Report.pdf [1]

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 "ICTV Taxonomy history: Enterovirus C" (in en). https://ictv.global/taxonomy/taxondetails?taxnode_id=201851985.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 "ICTV Taxonomy history: Enterovirus A" (in en). https://ictv.global/taxonomy/taxondetails?taxnode_id=201851983.

- ↑ "ICTV Taxonomy history: Human coxsackievirus A4" (in en). https://ictv.global/taxonomy/taxondetails?taxnode_id=19981965.

- ↑ "ICTV Taxonomy history: Human coxsackievirus A6" (in en). https://ictv.global/taxonomy/taxondetails?taxnode_id=19981967.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 "ICTV Taxonomy history: Enterovirus B" (in en). https://ictv.global/taxonomy/taxondetails?taxnode_id=201851984.

- ↑ "An Unidentified, Filtrable Agent Isolated From the Feces of Children With Paralysis". Science 108 (2794): 61–62. July 1948. doi:10.1126/science.108.2794.61. PMID 17777513. Bibcode: 1948Sci...108...61D.

- ↑ "A virus recovered from the feces of poliomyelitis patients pathogenic for suckling mice". J. Exp. Med. 89 (6): 567–82. June 1949. doi:10.1084/jem.89.6.567. PMID 18144319.

- ↑ Coxsackie NY and the virus named after it posted to Virology Blog 10 AUGUST 2009 by Professor Vincent Racaniello. Accessed via internet August 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Clinical and epidemiologic observations of Coxsackie-virus infection". N. Engl. J. Med. 244 (23): 868–73. June 1951. doi:10.1056/NEJM195106072442302. PMID 14843332.

- ↑ "Adaptation of Group B Coxsackie virus to adult mouse pancreas". J. Exp. Med. 96 (5): 491–7. November 1952. doi:10.1084/jem.96.5.491. PMID 13000059.

- ↑ "Susceptibility of gravid mice to Coxsackie virus infection". J. Exp. Med. 99 (1): 21–7. January 1954. doi:10.1084/jem.99.1.21. PMID 13118060.

- ↑ "Recognition of mouse ectromelia". Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 88 (2): 290–2. February 1955. doi:10.3181/00379727-88-21566. PMID 14357417.

- ↑ "China says it controls viral outbreak in children". Reuters. 2007-05-19. https://www.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUSPEK35841720070520?feedType=RSS..

- ↑ "Combination of soluble coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor and anti-coxsackievirus siRNAs exerts synergistic antiviral activity against coxsackievirus B3". Antiviral Res. 83 (3): 298–306. September 2009. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.07.002. PMID 19591879.

External links

|