Ratio distribution

A ratio distribution (also known as a quotient distribution) is a probability distribution constructed as the distribution of the ratio of random variables having two other known distributions. Given two (usually independent) random variables X and Y, the distribution of the random variable Z that is formed as the ratio Z = X/Y is a ratio distribution.

An example is the Cauchy distribution (also called the normal ratio distribution), which comes about as the ratio of two normally distributed variables with zero mean. Two other distributions often used in test-statistics are also ratio distributions: the t-distribution arises from a Gaussian random variable divided by an independent chi-distributed random variable, while the F-distribution originates from the ratio of two independent chi-squared distributed random variables. More general ratio distributions have been considered in the literature.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

Often the ratio distributions are heavy-tailed, and it may be difficult to work with such distributions and develop an associated statistical test. A method based on the median has been suggested as a "work-around".[10]

Algebra of random variables

The ratio is one type of algebra for random variables: Related to the ratio distribution are the product distribution, sum distribution and difference distribution. More generally, one may talk of combinations of sums, differences, products and ratios. Many of these distributions are described in Melvin D. Springer's book from 1979 The Algebra of Random Variables.[8]

The algebraic rules known with ordinary numbers do not apply for the algebra of random variables. For example, if a product is C = AB and a ratio is D=C/A it does not necessarily mean that the distributions of D and B are the same. Indeed, a peculiar effect is seen for the Cauchy distribution: The product and the ratio of two independent Cauchy distributions (with the same scale parameter and the location parameter set to zero) will give the same distribution.[8] This becomes evident when regarding the Cauchy distribution as itself a ratio distribution of two Gaussian distributions of zero means: Consider two Cauchy random variables, and each constructed from two Gaussian distributions and then

where . The first term is the ratio of two Cauchy distributions while the last term is the product of two such distributions.

Derivation

A way of deriving the ratio distribution of from the joint distribution of the two other random variables X , Y , with joint pdf , is by integration of the following form[3]

If the two variables are independent then and this becomes

This may not be straightforward. By way of example take the classical problem of the ratio of two standard Gaussian samples. The joint pdf is

Defining we have

Using the known definite integral we get

which is the Cauchy distribution, or Student's t distribution with n = 1

The Mellin transform has also been suggested for derivation of ratio distributions.[8]

In the case of positive independent variables, proceed as follows. The diagram shows a separable bivariate distribution which has support in the positive quadrant and we wish to find the pdf of the ratio . The hatched volume above the line represents the cumulative distribution of the function multiplied with the logical function . The density is first integrated in horizontal strips; the horizontal strip at height y extends from x = 0 to x = Ry and has incremental probability .

Secondly, integrating the horizontal strips upward over all y yields the volume of probability above the line

Finally, differentiate with respect to to get the pdf .

Move the differentiation inside the integral:

and since

then

As an example, find the pdf of the ratio R when

We have

thus

Differentiation wrt. R yields the pdf of R

Moments of random ratios

From Mellin transform theory, for distributions existing only on the positive half-line , we have the product identity provided are independent. For the case of a ratio of samples like , in order to make use of this identity it is necessary to use moments of the inverse distribution. Set such that . Thus, if the moments of and can be determined separately, then the moments of can be found. The moments of are determined from the inverse pdf of , often a tractable exercise. At simplest, .

To illustrate, let be sampled from a standard Gamma distribution

- whose -th moment is .

is sampled from an inverse Gamma distribution with parameter and has pdf . The moments of this pdf are

Multiplying the corresponding moments gives

Independently, it is known that the ratio of the two Gamma samples follows the Beta Prime distribution:

- whose moments are

Substituting we have which is consistent with the product of moments above.

Means and variances of random ratios

In the Product distribution section, and derived from Mellin transform theory (see section above), it is found that the mean of a product of independent variables is equal to the product of their means. In the case of ratios, we have

which, in terms of probability distributions, is equivalent to

Note that i.e.,

The variance of a ratio of independent variables is

Normal ratio distributions

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Normal ratio distributions. (Discuss) (March 2021) |

Uncorrelated central normal ratio

When X and Y are independent and have a Gaussian distribution with zero mean, the form of their ratio distribution is a Cauchy distribution. This can be derived by setting then showing that has circular symmetry. For a bivariate uncorrelated Gaussian distribution we have

If is a function only of r then is uniformly distributed on with density so the problem reduces to finding the probability distribution of Z under the mapping

We have, by conservation of probability

and since

and setting we get

There is a spurious factor of 2 here. Actually, two values of spaced by map onto the same value of z, the density is doubled, and the final result is

When either of the two Normal distributions is non-central then the result for the distribution of the ratio is much more complicated and is given below in the succinct form presented by David Hinkley.[6] The trigonometric method for a ratio does however extend to radial distributions like bivariate normals or a bivariate Student t in which the density depends only on radius . It does not extend to the ratio of two independent Student t distributions which give the Cauchy ratio shown in a section below for one degree of freedom.

Uncorrelated noncentral normal ratio

In the absence of correlation , the probability density function of the two normal variables X = N(μX, σX2) and Y = N(μY, σY2) ratio Z = X/Y is given exactly by the following expression, derived in several sources:[6]

where

and is the normal cumulative distribution function:

- Under several assumptions (usually fulfilled in practical applications), it is possible to derive a highly accurate solid approximation to the PDF. Main benefits are reduced formulae complexity, closed-form CDF, simple defined median, well defined error management, etc... For the sake of simplicity let's introduce parameters: , and . Then so called solid approximation to the uncorrelated noncentral normal ratio PDF is expressed by equation [11]

- Under certain conditions, a normal approximation is possible, with variance:[12]

Correlated central normal ratio

The above expression becomes more complicated when the variables X and Y are correlated. If but and the more general Cauchy distribution is obtained

where ρ is the correlation coefficient between X and Y and

The complex distribution has also been expressed with Kummer's confluent hypergeometric function or the Hermite function.[9]

Correlated noncentral normal ratio

This was shown in Springer 1979 problem 4.28.

A transformation to the log domain was suggested by Katz(1978) (see binomial section below). Let the ratio be

- .

Take logs to get

Since then asymptotically

Alternatively, Geary (1930) suggested that

has approximately a standard Gaussian distribution:[1] This transformation has been called the Geary–Hinkley transformation;[7] the approximation is good if Y is unlikely to assume negative values, basically .

Exact correlated noncentral normal ratio

This section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (November 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

This is developed by Dale (Springer 1979 problem 4.28) and Hinkley 1969. Geary showed how the correlated ratio could be transformed into a near-Gaussian form and developed an approximation for dependent on the probability of negative denominator values being vanishingly small. Fieller's later correlated ratio analysis is exact but care is needed when combining modern math packages with verbal conditions in the older literature. Pham-Ghia has exhaustively discussed these methods. Hinkley's correlated results are exact but it is shown below that the correlated ratio condition can also be transformed into an uncorrelated one so only the simplified Hinkley equations above are required, not the full correlated ratio version.

Let the ratio be:

in which are zero-mean correlated normal variables with variances and have means Write such that become uncorrelated and has standard deviation

The ratio:

is invariant under this transformation and retains the same pdf. The term in the numerator appears to be made separable by expanding:

to get

in which and z has now become a ratio of uncorrelated non-central normal samples with an invariant z-offset (this is not formally proven, though appears to have been used by Geary),

Finally, to be explicit, the pdf of the ratio for correlated variables is found by inputting the modified parameters and into the Hinkley equation above which returns the pdf for the correlated ratio with a constant offset on .

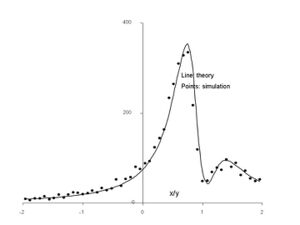

The figures above show an example of a positively correlated ratio with in which the shaded wedges represent the increment of area selected by given ratio which accumulates probability where they overlap the distribution. The theoretical distribution, derived from the equations under discussion combined with Hinkley's equations, is highly consistent with a simulation result using 5,000 samples. In the top figure it is clear that for a ratio the wedge has almost bypassed the main distribution mass altogether and this explains the local minimum in the theoretical pdf . Conversely as moves either toward or away from one the wedge spans more of the central mass, accumulating a higher probability.

Complex normal ratio

The ratio of correlated zero-mean circularly symmetric complex normal distributed variables was determined by Baxley et al.[13] and has since been extended to the nonzero-mean and nonsymmetric case.[14] In the correlated zero-mean case, the joint distribution of x, y is

where

is an Hermitian transpose and

The PDF of is found to be

In the usual event that we get

Further closed-form results for the CDF are also given.

The graph shows the pdf of the ratio of two complex normal variables with a correlation coefficient of . The pdf peak occurs at roughly the complex conjugate of a scaled down .

Ratio of log-normal

The ratio of independent or correlated log-normals is log-normal. This follows, because if and are log-normally distributed, then and are normally distributed. If they are independent or their logarithms follow a bivarate normal distribution, then the logarithm of their ratio is the difference of independent or correlated normally distributed random variables, which is normally distributed.[note 1]

This is important for many applications requiring the ratio of random variables that must be positive, where joint distribution of and is adequately approximated by a log-normal. This is a common result of the multiplicative central limit theorem, also known as Gibrat's law, when is the result of an accumulation of many small percentage changes and must be positive and approximately log-normally distributed.[15]

Uniform ratio distribution

With two independent random variables following a uniform distribution, e.g.,

the ratio distribution becomes

Cauchy ratio distribution

If two independent random variables, X and Y each follow a Cauchy distribution with median equal to zero and shape factor

then the ratio distribution for the random variable is[16]

This distribution does not depend on and the result stated by Springer[8] (p158 Question 4.6) is not correct. The ratio distribution is similar to but not the same as the product distribution of the random variable :

More generally, if two independent random variables X and Y each follow a Cauchy distribution with median equal to zero and shape factor and respectively, then:

- The ratio distribution for the random variable is[16]

- The product distribution for the random variable is[16]

The result for the ratio distribution can be obtained from the product distribution by replacing with

Ratio of standard normal to standard uniform

If X has a standard normal distribution and Y has a standard uniform distribution, then Z = X / Y has a distribution known as the slash distribution, with probability density function

where φ(z) is the probability density function of the standard normal distribution.[17]

Chi-squared, Gamma, Beta distributions

Let G be a normal(0,1) distribution, Y and Z be chi-squared distributions with m and n degrees of freedom respectively, all independent, with . Then

- the Student's t distribution

- i.e. Fisher's F-test distribution

- the beta distribution

- the standard beta prime distribution

If , a noncentral chi-squared distribution, and and is independent of then

defines , Fisher's F density distribution, the PDF of the ratio of two Chi-squares with m, n degrees of freedom.

The CDF of the Fisher density, found in F-tables is defined in the beta prime distribution article. If we enter an F-test table with m = 3, n = 4 and 5% probability in the right tail, the critical value is found to be 6.59. This coincides with the integral

For gamma distributions U and V with arbitrary shape parameters α1 and α2 and their scale parameters both set to unity, that is, , where , then

If , then . Note that here θ is a scale parameter, rather than a rate parameter.

If , then by rescaling the parameter to unity we have

Thus

in which represents the generalised beta prime distribution.

In the foregoing it is apparent that if then . More explicitly, since

if then

where

Rayleigh Distributions

If X, Y are independent samples from the Rayleigh distribution , the ratio Z = X/Y follows the distribution[18]

and has cdf

The Rayleigh distribution has scaling as its only parameter. The distribution of follows

and has cdf

Fractional gamma distributions (including chi, chi-squared, exponential, Rayleigh and Weibull)

The generalized gamma distribution is

which includes the regular gamma, chi, chi-squared, exponential, Rayleigh, Nakagami and Weibull distributions involving fractional powers. Note that here a is a scale parameter, rather than a rate parameter; d is a shape parameter.

- If

- then[19]

- where

Modelling a mixture of different scaling factors

In the ratios above, Gamma samples, U, V may have differing sample sizes but must be drawn from the same distribution with equal scaling .

In situations where U and V are differently scaled, a variables transformation allows the modified random ratio pdf to be determined. Let where arbitrary and, from above, .

Rescale V arbitrarily, defining

We have and substitution into Y gives

Transforming X to Y gives

Noting we finally have

Thus, if and

then is distributed as with

The distribution of Y is limited here to the interval [0,1]. It can be generalized by scaling such that if then

where

- is then a sample from

Reciprocals of samples from beta distributions

Though not ratio distributions of two variables, the following identities for one variable are useful:

- If then

- If then

combining the latter two equations yields

- If then .

- If then

since

then

- , the distribution of the reciprocals of samples.

If then and

Further results can be found in the Inverse distribution article.

- If are independent exponential random variables with mean μ, then X − Y is a double exponential random variable with mean 0 and scale μ.

Binomial distribution

This result was first derived by Katz et al. in 1978.[20]

Suppose and and , are independent. Let .

Then is approximately normally distributed with mean and variance .

The binomial ratio distribution is of significance in clinical trials: if the distribution of T is known as above, the probability of a given ratio arising purely by chance can be estimated, i.e. a false positive trial. A number of papers compare the robustness of different approximations for the binomial ratio.[citation needed]

Poisson and truncated Poisson distributions

In the ratio of Poisson variables R = X/Y there is a problem that Y is zero with finite probability so R is undefined. To counter this, we consider the truncated, or censored, ratio R' = X/Y' where zero sample of Y are discounted. Moreover, in many medical-type surveys, there are systematic problems with the reliability of the zero samples of both X and Y and it may be good practice to ignore the zero samples anyway.

The probability of a null Poisson sample being , the generic pdf of a left truncated Poisson distribution is

which sums to unity. Following Cohen,[21] for n independent trials, the multidimensional truncated pdf is

and the log likelihood becomes

On differentiation we get

and setting to zero gives the maximum likelihood estimate

Note that as then so the truncated maximum likelihood estimate, though correct for both truncated and untruncated distributions, gives a truncated mean value which is highly biassed relative to the untruncated one. Nevertheless it appears that is a sufficient statistic for since depends on the data only through the sample mean in the previous equation which is consistent with the methodology of the conventional Poisson distribution.

Absent any closed form solutions, the following approximate reversion for truncated is valid over the whole range .

which compares with the non-truncated version which is simply . Taking the ratio is a valid operation even though may use a non-truncated model while has a left-truncated one.

The asymptotic large- (and Cramér–Rao bound) is

in which substituting L gives

Then substituting from the equation above, we get Cohen's variance estimate

The variance of the point estimate of the mean , on the basis of n trials, decreases asymptotically to zero as n increases to infinity. For small it diverges from the truncated pdf variance in Springael[22] for example, who quotes a variance of

for n samples in the left-truncated pdf shown at the top of this section. Cohen showed that the variance of the estimate relative to the variance of the pdf, , ranges from 1 for large (100% efficient) up to 2 as approaches zero (50% efficient).

These mean and variance parameter estimates, together with parallel estimates for X, can be applied to Normal or Binomial approximations for the Poisson ratio. Samples from trials may not be a good fit for the Poisson process; a further discussion of Poisson truncation is by Dietz and Bohning[23] and there is a Zero-truncated Poisson distribution Wikipedia entry.

Double Lomax distribution

This distribution is the ratio of two Laplace distributions.[24] Let X and Y be standard Laplace identically distributed random variables and let z = X / Y. Then the probability distribution of z is

Let the mean of the X and Y be a. Then the standard double Lomax distribution is symmetric around a.

This distribution has an infinite mean and variance.

If Z has a standard double Lomax distribution, then 1/Z also has a standard double Lomax distribution.

The standard Lomax distribution is unimodal and has heavier tails than the Laplace distribution.

For 0 < a < 1, the a-th moment exists.

where Γ is the gamma function.

Ratio distributions in multivariate analysis

Ratio distributions also appear in multivariate analysis.[25] If the random matrices X and Y follow a Wishart distribution then the ratio of the determinants

is proportional to the product of independent F random variables. In the case where X and Y are from independent standardized Wishart distributions then the ratio

has a Wilks' lambda distribution.

Ratios of Quadratic Forms involving Wishart Matrices

Probability distribution can be derived from random quadratic forms

where and/or are random.[26] If A is the inverse of another matrix B then is a random ratio in some sense, frequently arising in Least Squares estimation problems.

In the Gaussian case if A is a matrix drawn from a complex Wishart distribution of dimensionality p x p and k degrees of freedom with while is an arbitrary complex vector with Hermitian (conjugate) transpose , the ratio

follows the Gamma distribution

The result arises in least squares adaptive Wiener filtering - see eqn(A13) of.[25] Note that the original article contends that the distribution is .

Similarly, for full-rank ( zero-mean real-valued Wishart matrix samples , and V a random vector independent of W, the ratio

This result is usually attributed to Muirhead (1982).[27]

Given complex Wishart matrix , the ratio

follows the Beta distribution (see eqn(47) of[28])

The result arises in the performance analysis of constrained least squares filtering and derives from a more complex but ultimately equivalent ratio that if then

In its simplest form, if and then the ratio of the (1,1) inverse element squared to the sum of modulus squares of the whole top row elements has distribution

See also

- Relationships among probability distributions

- Inverse distribution (also known as reciprocal distribution)

- Product distribution

- Ratio estimator

- Slash distribution

Notes

- ↑ Note, however, that and can be individually log-normally distributed without having a bivariate log-normal distribution. As of 2022-06-08 the Wikipedia article on "Copula (probability theory)" includes a density and contour plot of two Normal marginals joint with a Gumbel copula, where the joint distribution is not bivariate normal.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Geary, R. C. (1930). "The Frequency Distribution of the Quotient of Two Normal Variates". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 93 (3): 442–446. doi:10.2307/2342070.

- ↑ Fieller, E. C. (November 1932). "The Distribution of the Index in a Normal Bivariate Population". Biometrika 24 (3/4): 428–440. doi:10.2307/2331976.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Curtiss, J. H. (December 1941). "On the Distribution of the Quotient of Two Chance Variables". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 12 (4): 409–421. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177731679.

- ↑ George Marsaglia (April 1964). Ratios of Normal Variables and Ratios of Sums of Uniform Variables. Defense Technical Information Center.

- ↑ Marsaglia, George (March 1965). "Ratios of Normal Variables and Ratios of Sums of Uniform Variables". Journal of the American Statistical Association 60 (309): 193–204. doi:10.2307/2283145. http://www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=AD0600972.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Hinkley, D. V. (December 1969). "On the Ratio of Two Correlated Normal Random Variables". Biometrika 56 (3): 635–639. doi:10.2307/2334671.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hayya, Jack; Armstrong, Donald; Gressis, Nicolas (July 1975). "A Note on the Ratio of Two Normally Distributed Variables". Management Science 21 (11): 1338–1341. doi:10.1287/mnsc.21.11.1338.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Springer, Melvin Dale (1979). The Algebra of Random Variables. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-01406-0. https://archive.org/details/algebraofrandomv0000spri.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pham-Gia, T.; Turkkan, N.; Marchand, E. (2006). "Density of the Ratio of Two Normal Random Variables and Applications". Communications in Statistics – Theory and Methods (Taylor & Francis) 35 (9): 1569–1591. doi:10.1080/03610920600683689.

- ↑ Brody, James P.; Williams, Brian A.; Wold, Barbara J.; Quake, Stephen R. (October 2002). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 (20): 12975–12978. doi:10.1073/pnas.162468199. PMID 12235357. PMC 130571. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...9912975B. http://authors.library.caltech.edu/685/1/BROpnas02.pdf.

- ↑ Šimon, Ján; Ftorek, Branislav (2022-09-15). "Basic Statistical Properties of the Knot Efficiency". Symmetry (MDPI) 14 (9): 1926. doi:10.3390/sym14091926. ISSN 2073-8994.

- ↑ Díaz-Francés, Eloísa; Rubio, Francisco J. (2012-01-24). "On the existence of a normal approximation to the distribution of the ratio of two independent normal random variables". Statistical Papers (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 54 (2): 309–323. doi:10.1007/s00362-012-0429-2. ISSN 0932-5026.

- ↑ Baxley, R T; Waldenhorst, B T; Acosta-Marum, G (2010). "Complex Gaussian Ratio Distribution with Applications for Error Rate Calculation in Fading Channels with Imperfect CSI". 2010 IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference GLOBECOM 2010. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1109/GLOCOM.2010.5683407. ISBN 978-1-4244-5636-9. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224210655.

- ↑ Sourisseau, M.; Wu, H.-T.; Zhou, Z. (October 2022). "Asymptotic analysis of synchrosqueezing transform—toward statistical inference with nonlinear-type time-frequency analysis". Annals of Statistics 50 (5): 2694-2712. doi:10.1214/22-AOS2203. https://projecteuclid.org/journals/annals-of-statistics/volume-50/issue-5/Asymptotic-analysis-of-synchrosqueezing-transformtoward-statistical-inference-with-nonlinear-type/10.1214/22-AOS2203.short?tab=ArticleLinkReference.

- ↑ Of course, any invocation of a central limit theorem assumes suitable, commonly met regularity conditions, e.g., finite variance.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Kermond, John (2010). "An Introduction to the Algebra of Random Variables". Mathematical Association of Victoria 47th Annual Conference Proceedings – New Curriculum. New Opportunities (The Mathematical Association of Victoria): 1–16. ISBN 978-1-876949-50-1.

- ↑ "SLAPPF". Statistical Engineering Division, National Institute of Science and Technology. http://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/software/dataplot/refman2/auxillar/slappf.htm.

- ↑ Hamedani, G. G. (Oct 2013). "Characterizations of Distribution of Ratio of Rayleigh Random Variables". Pakistan Journal of Statistics 29 (4): 369–376.

- ↑ Raja Rao, B.; Garg., M. L. (1969). "A note on the generalized (positive) Cauchy distribution". Canadian Mathematical Bulletin 12 (6): 865–868. doi:10.4153/CMB-1969-114-2.

- ↑ Katz D. et al.(1978) Obtaining confidence intervals for the risk ratio in cohort studies. Biometrics 34:469–474

- ↑ Cohen, A Clifford (June 1960). "Estimating the Parameter in a Conditional Poisson Distribution". Biometrics 60 (2): 203–211. doi:10.2307/2527552.

- ↑ Springael, Johan (2006). "On the sum of independent zero-truncated Poisson random variables". https://repository.uantwerpen.be/docman/irua/b66c5a/4743e891.pdf.

- ↑ Dietz, Ekkehart; Bohning, Dankmar (2000). "On Estimation of the Poisson Parameter in Zero-Modified Poisson Models". Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 34 (4): 441–459. doi:10.1016/S0167-9473(99)00111-5.

- ↑ Bindu P and Sangita K (2015) Double Lomax distribution and its applications. Statistica LXXV (3) 331–342

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Brennan, L E; Reed, I S (January 1982). "An Adaptive Array Signal Processing Algorithm for Communications". IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems AES-18 No 1: 124–130. doi:10.1109/TAES.1982.309212. Bibcode: 1982ITAES..18..124B.

- ↑ Mathai, A M; Provost, L (1992). Quadratic Forms in Random Variables. New York: Mercel Decker Inc.. ISBN 0-8247-8691-2. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224817325.

- ↑ Muirhead, Robb (1982). Aspects of Multivariate Statistical Theory. USA: Wiley. pp. 96; Theorem 3.2.12.

- ↑ Reed, I S; Mallett, J D; Brennan, L E (November 1974). "Rapid Convergence Rate in Adaptive Arrays". IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems AES-10 No.6 (6): 853–863. doi:10.1109/TAES.1974.307893. Bibcode: 1974ITAES..10..853R.

External links

- Ratio Distribution at MathWorld

- Normal Ratio Distribution at MathWorld

- Ratio Distributions at MathPages

|