Physics:Defining equation

In physics, defining equations are equations that define new quantities in terms of base quantities.[1] This article uses the current SI system of units, not natural or characteristic units.

Description of units and physical quantities

Physical quantities and units follow the same hierarchy; chosen base quantities have defined base units, from these any other quantities may be derived and have corresponding derived units.

Colour mixing analogy

Defining quantities is analogous to mixing colours, and could be classified a similar way, although this is not standard. Primary colours are to base quantities; as secondary (or tertiary etc.) colours are to derived quantities. Mixing colours is analogous to combining quantities using mathematical operations. But colours could be for light or paint, and analogously the system of units could be one of many forms: such as SI (now most common), CGS, Gaussian, old imperial units, a specific form of natural units or even arbitrarily defined units characteristic to the physical system in consideration (characteristic units).

The choice of a base system of quantities and units is arbitrary; but once chosen it must be adhered to throughout all analysis which follows for consistency. It makes no sense to mix up different systems of units. Choosing a system of units, one system out of the SI, CGS etc., is like choosing whether use paint or light colours.

In light of this analogy, primary definitions are base quantities with no defining equation, but defined standardized condition, "secondary" definitions are quantities defined purely in terms of base quantities, "tertiary" for quantities in terms of both base and "secondary" quantities, "quaternary" for quantities in terms of base, "secondary", and "tertiary" quantities, and so on.

Motivation

Much of physics requires definitions to be made for the equations to make sense.

Theoretical implications: Definitions are important since they can lead into new insights of a branch of physics. Two such examples occurred in classical physics. When entropy S was defined – the range of thermodynamics was greatly extended by associating chaos and disorder with a numerical quantity that could relate to energy and temperature, leading to the understanding of the second thermodynamic law and statistical mechanics.[2]

Also the action functional (also written S) (together with generalized coordinates and momenta and the Lagrangian function), initially an alternative formulation of classical mechanics to Newton's laws, now extends the range of modern physics in general – notably quantum mechanics, particle physics, and general relativity.[3]

Analytical convenience: They allow other equations to be written more compactly and so allow easier mathematical manipulation; by including a parameter in a definition, occurrences of the parameter can be absorbed into the substituted quantity and removed from the equation.[4]

- Example

As an example consider Ampère's circuital law (with Maxwell's correction) in integral form for an arbitrary current carrying conductor in a vacuum (so zero magnetization due medium, i.e. M = 0):[5] [math]\displaystyle{ \oint_S \mathbf{B} \cdot d\mathbf{l}= \mu_0 \oint_S \left ( \mathbf{J} + \varepsilon_0 \frac{\partial \mathbf{E}}{\partial t} \right ) \cdot d\mathbf{A} }[/math] using the constitutive definition [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{B} = \mu_0 \mathbf{H}, }[/math] and the current density definition [math]\displaystyle{ I = \oint_S \mathbf{J} \cdot d \mathbf{A} , }[/math] similarly for the displacement current density [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{J}_{\rm d} = \epsilon_0 \frac{\partial \mathbf{E}}{\partial t} }[/math] leading to the displacement current [math]\displaystyle{ I_d = \oint_S \mathbf{J}_\text{d} \cdot d\mathbf{A} , }[/math] we have [math]\displaystyle{ \oint_S \mathbf{B} \cdot d\mathbf{l}= \mu_0 \oint_S \mathbf{J} \cdot d\mathbf{A} + \mu_0 \oint_S \mathbf{J} _\text{d} \cdot d\mathbf{A}, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \oint_S \mathbf{H} \cdot d\mathbf{l} = I + I_d, }[/math] which is simpler to write, even if the equation is the same.

Ease of comparison: They allow comparisons of measurements to be made when they might appear ambiguous and unclear otherwise.

- Example

A basic example is mass density. It is not clear how compare how much matter constitutes a variety of substances given only their masses or only their volumes. Given both for each substance, the mass m per unit volume V, or mass density ρ provides a meaningful comparison between the substances, since for each, a fixed amount of volume will correspond to an amount of mass depending on the substance. To illustrate this; if two substances A and B have masses mA and mB respectively, occupying volumes VA and VB respectively, using the definition of mass density gives:

- ρA = mA / VA , ρB = mB / VB

following this can be seen that:

- if mA > mB or mA < mB and VA = VB, then ρA > ρB or ρA < ρB,

- if mA = mB and VA > VB or VA < VB, then ρA < ρB or ρA > ρB,

- if ρA = ρB, then mA / VA = mB / VB so mA / mB = VA / VB, demonstrating that if mA > mB or mA < mB, then VA > VB or VA < VB.

Making such comparisons without using mathematics logically in this way would not be as systematic.

Construction of defining equations

Scope of definitions

Defining equations are normally formulated in terms of elementary algebra and calculus, vector algebra and calculus, or for the most general applications tensor algebra and calculus, depending on the level of study and presentation, complexity of topic and scope of applicability. Functions may be incorporated into a definition, in for calculus this is necessary. Quantities may also be complex-valued for theoretical advantage, but for a physical measurement the real part is relevant, the imaginary part can be discarded. For more advanced treatments the equation may have to be written in an equivalent but alternative form using other defining equations for the definition to be useful. Often definitions can start from elementary algebra, then modify to vectors, then in the limiting cases calculus may be used. The various levels of maths used typically follows this pattern.

Typically definitions are explicit, meaning the defining quantity is the subject of the equation, but sometimes the equation is not written explicitly – although the defining quantity can be solved for to make the equation explicit. For vector equations, sometimes the defining quantity is in a cross or dot product and cannot be solved for explicitly as a vector, but the components can.

- Examples

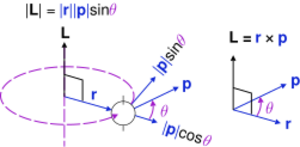

Electric current density is an example spanning all of these methods, Angular momentum is an example which doesn't require calculus. See the classical mechanics section below for nomenclature and diagrams to the right.

Elementary algebra

Operations are simply multiplication and division. Equations may be written in a product or quotient form, both of course equivalent.

Angular momentum Electric current density Quotient form [math]\displaystyle{ p = \frac{L}{r} \,\! }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ J = \frac{I}{A} \,\! }[/math] Product form [math]\displaystyle{ L = pr \,\! }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ I = J A \,\! }[/math]

Vector algebra

There is no way to divide a vector by a vector, so there are no product or quotient forms.

Angular momentum Electric current density Quotient form N/A [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{J} \cdot \mathbf{\hat{n}} = \frac{I}{A} \,\! }[/math] Product form Starting from [math]\displaystyle{ L = p r , \,\! }[/math]

since L = 0 when p and r are parallel or antiparallel, and is a maximum when perpendicular, so that the only component of p which contributes to L is the tangential |p| sin θ, the magnitude of angular momentum L should be re-written as

[math]\displaystyle{ L = p r \sin \theta .\,\! }[/math]

Since r, p and L form a right-hand triad, this leads to the vector form

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{L} = \mathbf{r} \times \mathbf{p} .\,\! }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{J} \cdot \mathbf{\hat{n}} A = I ,\,\! }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{J} \cdot\mathbf{A} = I , \,\! }[/math]

Elementary calculus

- The arithmetic operations are modified to the limiting cases of differentiation and integration. Equations can be expressed in these equivalent and alternative ways.

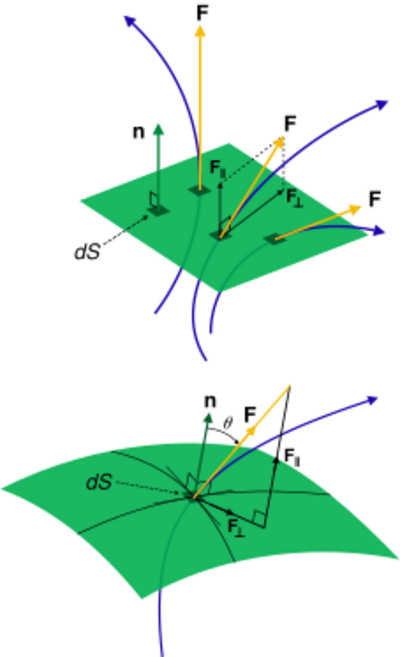

Current density Differential form [math]\displaystyle{ J = \lim_{A \rightarrow 0} \frac{I}{A} = \frac{\mathrm{d}I}{\mathrm{d}A} \,\! }[/math] Integral form [math]\displaystyle{ I = \lim_{A_i \rightarrow 0} \sum_i J A_i = \int_S J {\mathrm{d} A} \,\! }[/math] where dA means a differential area element (see also surface integral).

Alternatively for integral form

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{d} I = J {\mathrm{d} A} , \,\! }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ I = \int_S J {\mathrm{d} A} . \,\! }[/math]

Vector calculus

Current density Differential form [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{J} \cdot \mathbf{\hat{n}} = \frac{\mathrm{d}I}{\mathrm{d}A} \,\! }[/math] Integral form [math]\displaystyle{ I = \int_S \mathbf{J} \cdot \mathrm{d} \mathbf{A} \,\! }[/math] where dA = ndA is the differential vector area.

Tensor analysis

Vectors are rank-1 tensors. The formulae below are no more than the vector equations in the language of tensors.

Angular momentum Electric current density Differential form N/A [math]\displaystyle{ J_i n_i = \frac{\mathrm{d} I}{\mathrm{d} A} \,\! }[/math] Product/integral form Starting from [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{L} = \mathbf{r} \times \mathbf{p} \,\! }[/math]

the components are Li, rj, pi, where i, j, k are each dummy indices each taking values 1, 2, 3, using the identity from tensor analysis

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{a} = \mathbf{b} \times \mathbf{c}, \quad a_i = \epsilon_{ijk} b_j c_k ,\,\! }[/math]

where εijk is the permutation/Levi-Cita tensor, leads to

[math]\displaystyle{ L_i = \epsilon_{ijk} r_j p_k .\,\! }[/math]

Using the Einstein summation convention, [math]\displaystyle{ J_i n_i \mathrm{d} A = \mathrm{d} I \,\! }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \int_S J_i \mathrm{d} A_i = I \,\! }[/math]

Multiple choice definitions

Sometimes there is still freedom within the chosen units system, to define one or more quantities in more than one way. The situation splits into two cases:[6]

Mutually exclusive definitions: There are a number of possible choices for a quantity to be defined in terms of others, but only one can be used and not the others. Choosing more than one of the exclusive equations for a definition leads to a contradiction – one equation might demand a quantity X to be defined in one way using another quantity Y, while another equation requires the reverse, Y be defined using X, but then another equation might falsify the use of both X and Y, and so on. The mutual disagreement makes it impossible to say which equation defines what quantity.

Equivalent definitions: Defining equations which are equivalent and self-consistent with other equations and laws within the physical theory, simply written in different ways.

There are two possibilities for each case:

One defining equation – one defined quantity: A defining equation is used to define a single quantity in terms of a number of others.

One defining equation – a number of defined quantities: A defining equation is used to define a number of quantities in terms of a number of others. A single defining equation shouldn't contain one quantity defining all other quantities in the same equation, otherwise contradictions arise again. There is no definition of the defined quantities separately since they are defined by a single quantity in a single equation. Furthermore, the defined quantities may have already been defined before, so if another quantity defines these in the same equation, there is a clash between definitions.

Contradictions can be avoided by defining quantities successively; the order in which quantities are defined must be accounted for. Examples spanning these instances occur in electromagnetism, and are given below.

- Examples

Mutually exclusive definitions:

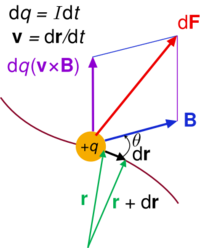

The magnetic induction field B can be defined in terms of electric charge q or current I, and the Lorentz force (magnetic term) F experienced by the charge carriers due to the field,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{F} & = q \left ( \mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{B} \right ) \\ & = \left ( \int I \mathrm{d} t \right ) \left ( \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{r}}{\mathrm{d} t} \times \mathbf{B} \right ) \\ & = \left ( \int I \mathrm{d} t \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{r}}{\mathrm{d} t} \right ) \times \mathbf{B} \\ & = I \left ( \int \mathrm{d}\mathbf{r} \right ) \times \mathbf{B} \\ & = I \left ( \mathbf{l} \times \mathbf{B} \right ), \end{align} \,\! }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{l} = \int \mathrm{d}\mathbf{r} \,\! }[/math] is the change in position traversed by the charge carriers (assuming current is independent of position, if not so a line integral must be done along the path of current) or in terms of the magnetic flux ΦB through a surface S, where the area is used as a scalar A and vector: [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{A} = A\mathbf{\hat{n}} \,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\hat{n}} \,\! }[/math] is a unit normal to A, either in differential form

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{B} \cdot \mathbf{\hat{n}} = \frac{\mathrm{d}\Phi_B}{\mathrm{d}A} ,\,\! }[/math]

or integral form,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{B} \cdot \mathbf{\hat{n}} \mathrm{d}A = \mathrm{d}\Phi_B ,\,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi_B = \int_S \mathbf{B} \cdot \mathrm{d}\mathbf{A} .\,\! }[/math]

However, only one of the above equations can be used to define B for the following reason, given that A, r, v, and F have been defined elsewhere unambiguously (most likely mechanics and Euclidean geometry).

If the force equation defines B, where q or I have been previously defined, then the flux equation defines ΦB, since B has been previously defined unambiguously. If the flux equation defines B, where ΦB, the force equation may be a defining equation for I or q. Notice the contradiction when B both equations define B simultaneously and when B is not a base quantity; the force equation demands that q or I be defined elsewhere while at the same time the flux equation demands that q or I be defined by the force equation, similarly the force equation requires ΦB to be defined by the flux equation, at the same time the flux equation demands that ΦB is defined elsewhere. For both equations to be used as definitions simultaneously, B must be a base quantity so that F and ΦB can be defined to stem from B unambiguously.[6]

Equivalent definitions:

Another example is inductance L which has two equivalent equations to use as a definition.[7][8]

In terms of I and ΦB, the inductance is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ L = N \frac{\mathrm{d}\Phi_B}{\mathrm{d} I} ,\,\! }[/math]

in terms of I and induced emf V

- [math]\displaystyle{ V = - L \frac{\mathrm{d}I}{\mathrm{d} t} .\,\! }[/math]

These two are equivalent by Faraday's law of induction:

- [math]\displaystyle{ V = - N \frac{\mathrm{d}\Phi_B}{\mathrm{d} t} , \,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ V {\mathrm{d} t} = - N \mathrm{d}\Phi_B , \,\! }[/math]

substituting into the first definition for L

- [math]\displaystyle{ L = - V \frac{{\mathrm{d} t}}{\mathrm{d} I} \,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ V = - L \frac{\mathrm{d}I}{\mathrm{d} t} \,\! }[/math]

and so they are not mutually exclusive.

One defining equation – a number of defined quantities

Notice that L cannot define I and ΦB simultaneously - this makes no sense. I, ΦB and V have most likely all been defined before as (ΦB given above in flux equation);

- [math]\displaystyle{ V = \frac{\mathrm{d}W}{\mathrm{d} q} , \quad I = \frac{\mathrm{d}q}{\mathrm{d} t} ,\,\! }[/math]

where W = work done on charge q. Furthermore, there is no definition of either I or ΦB separately – because L is defining them in the same equation.

However, using the Lorentz force for the electromagnetic field:[9][10][11]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{F} = q \left [ \mathbf{E} + \left ( \mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{B} \right )\right ] ,\,\! }[/math]

as a single defining equation for the electric field E and magnetic field B is allowed, since E and B are not only defined by one variable, but three; force F, velocity v and charge q. This is consistent with isolated definitions of E and B since E is defined using F and q:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E} = \mathbf{F}/q .\,\! }[/math]

and B defined by F, v, and q, as given above.

Limitations of definitions

Definitions vs. functions: Defining quantities can vary as a function of parameters other than those in the definition. A defining equation only defines how to calculate the defined quantity, it cannot describe how the quantity varies as a function of other parameters since the function would vary from one application to another. How the defined quantity varies as a function of other parameters is described by a constitutive equation or equations, since it varies from one application to another and from one approximation (or simplification) to another.

- Examples

Mass density ρ is defined using mass m and volume V by but can vary as a function of temperature T and pressure p, ρ = ρ(p, T)

The angular frequency ω of wave propagation is defined using the frequency (or equivalently time period T) of the oscillation, as a function of wavenumber k, ω = ω(k). This is the dispersion relation for wave propagation.

The coefficient of restitution for an object colliding is defined using the speeds of separation and approach with respect to the collision point, but depends on the nature of the surfaces in question.

Definitions vs. theorems: There is a very important difference between defining equations and general or derived results, theorems or laws. Defining equations do not find out any information about a physical system, they simply re-state one measurement in terms of others. Results, theorems, and laws, on the other hand do provide meaningful information, if only a little, since they represent a calculation for a quantity given other properties of the system, and describe how the system behaves as variables are changed.

- Examples

An example was given above for Ampere's law. Another is the conservation of momentum for N1 initial particles having initial momenta pi where i = 1, 2 ... N1, and N2 final particles having final momenta pi (some particles may explode or adhere) where j = 1, 2 ... N2, the equation of conservation reads:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_i^{N_1}\mathbf{p}_{\rm i} = \sum_j^{N_2}\mathbf{p}_{\rm j} \,\! }[/math]

Using the definition of momentum in terms of velocity:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{p} = m \mathbf{v} \,\! }[/math]

so that for each particle:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{p}_{\rm i} = m_i \mathbf{v}_{\rm i} \,\! }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{p}_{\rm j} = m_j \mathbf{v}_{\rm j} \,\! }[/math]

the conservation equation can be written as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_i^{N_1}m_i \mathbf{v}_{\rm i} = \sum_j^{N_2} m_i \mathbf{v}_{\rm i} .\,\! }[/math]

It is identical to the previous version. No information is lost or gained by changing quantities when definitions are substituted, but the equation itself does give information about the system.

One-off definitions

Some equations, typically results from a derivation, include useful quantities which serve as a one-off definition within its scope of application.

- Examples

In special relativity, relativistic mass has support and detraction by physicists.[12] It is defined as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ m = \gamma m_0 \,\! }[/math]

where m0 is the rest mass of the object and γ is the Lorentz factor. This makes some quantities such as momentum p and energy E of a massive object in motion easy to obtain from other equations simply by using relativistic mass:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{p} = m\mathbf{v} \rightarrow \mathbf{p} = \gamma m_0 \mathbf{v} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ E = mc^2 \rightarrow E = \gamma m_0 c^2 }[/math]

However, this does not always apply, for instance the kinetic energy T and force F of the same object is not given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ T = \frac{m}{2}\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{v} \nrightarrow T = \frac{\gamma m_0}{2}\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{v} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{F} = m\mathbf{a} \nrightarrow \mathbf{F} = \gamma m_0 \mathbf{a} }[/math]

The Lorentz factor has a deeper significance and origin, and is used in terms of proper time and coordinate time with four-vectors. The correct equations above are consequence of the applying definitions in the correct order.

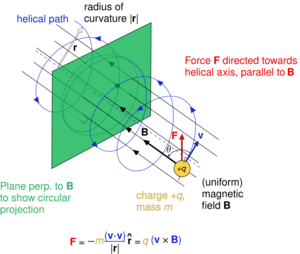

In electromagnetism, a charged particle (of mass m and charge q) in a uniform magnetic field B is deflected by the field in a circular helical arc at velocity v and radius of curvature r, where the helical trajectory inclined at an angle θ to B. The magnetic force is the centripetal force, so the force F acting on the particle is;

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{F} = - \frac{m \left ( \mathbf{v}\cdot{\mathbf{v}} \right ) \mathbf{\hat{r}} }{\left | \mathbf{r} \right |} = q \left ( \mathbf{v}\times \mathbf{B}\right ),\,\! }[/math]

reducing to scalar form and solving for |B||r|;

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{m \left | \mathbf{v} \right |^2 }{\left | \mathbf{r} \right |} = q \left | \mathbf{v} \right | \left | \mathbf{B} \right | \sin \theta, \,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{m \left | \mathbf{v} \right | }{\left | \mathbf{r} \right |} = q \left | \mathbf{B} \right | \sin \theta, \,\! }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left | \mathbf{B} \right | \left | \mathbf{r} \right | = \frac{m \left | \mathbf{v} \right | }{ q \sin \theta} , \,\! }[/math]

serves as the definition for the magnetic rigidity of the particle.[13] Since this depends on the mass and charge of the particle, it is useful for determining the extent a particle deflects in a B field, which occurs experimentally in mass spectrometry and particle detectors.

See also

- Constitutive equation

- Defining equation (physical chemistry)

- List of electromagnetism equations

- List of equations in classical mechanics

- List of equations in fluid mechanics

- List of equations in gravitation

- List of equations in nuclear and particle physics

- List of equations in quantum mechanics

- List of optics equations

- List of relativistic equations

- Table of thermodynamic equations

Footnotes

- ↑ Warlimont, pp 12–13

- ↑ P.W. Atkins (1978). Physical chemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 124–131. ISBN 0-19-855148-7.

- ↑ E. Abers (2004). Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-13-146100-0.

- ↑ P.M. Whelan; M.J. Hodgeson (1978). Essential Principles of Physics (2nd ed.). John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-3382-1.

- ↑ I.S. Grant; W.R. Phillips; Manchester Physics (2008). Electromagnetism (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 186–188. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9. https://archive.org/details/electromagnetism0000gran.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 P.M. Whelan; M.J. Hodgeson (1978). Essential Principles of Physics (2nd ed.). John Murray. p. 6. ISBN 0-7195-3382-1.

- ↑ P.M. Whelan; M.J. Hodgeson (1978). Essential Principles of Physics (2nd ed.). John Murray. p. 405. ISBN 0-7195-3382-1.

- ↑ I.S. Grant; W.R. Phillips; Manchester Physics (2008). Electromagnetism (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 231–234. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9. https://archive.org/details/electromagnetism0000gran.

- ↑ See, for example, Jackson p 777–8.

- ↑ J.A. Wheeler; C. Misner; K.S. Thorne (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman & Co. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0. https://archive.org/details/gravitation00misn_003.. These authors use the Lorentz force in tensor form as definer of the electromagnetic tensor F, in turn the fields E and B.

- ↑ I.S. Grant; W.R. Phillips; Manchester Physics (2008). Electromagnetism (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9. https://archive.org/details/electromagnetism0000gran.

- ↑ H.D. Young; R.A. Freedman (2008). University Physics – With Modern Physics (12th ed.). Addison-Wesley (Pearson International). pp. 1290–1291. ISBN 978-0-321-50130-1.

- ↑ I.S. Grant; W.R. Phillips; Manchester Physics (2008). Electromagnetism (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9. https://archive.org/details/electromagnetism0000gran.

Sources

- P.M. Whelan; M.J. Hodgeson (1978). Essential Principles of Physics (2nd ed.). John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-3382-1.

- G. Woan (2010). The Cambridge Handbook of Physics Formulas. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57507-2. https://archive.org/details/cambridgehandboo0000woan.

- A. Halpern (1988). 3000 Solved Problems in Physics, Schaum Series. Mc Graw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-025734-4.

- R.G. Lerner; G.L. Trigg (2005). Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.). VHC Publishers, Hans Warlimont, Springer. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-07-025734-4.

- C.B. Parker (1994). McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-051400-3. https://archive.org/details/mcgrawhillencycl1993park.

- P.A. Tipler; G. Mosca (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: With Modern Physics (6th ed.). W.H. Freeman and Co. ISBN 978-1-4292-0265-7.

- L.N. Hand; J.D. Finch (2008). Analytical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57572-0.

- T.B. Arkill; C.J. Millar (1974). Mechanics, Vibrations and Waves. John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-2882-8.

- H.J. Pain (1983). The Physics of Vibrations and Waves (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-90182-2.

- J.R. Forshaw; A.G. Smith (2009). Dynamics and Relativity. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-01460-8.

- G.A.G. Bennet (1974). Electricity and Modern Physics (2nd ed.). Edward Arnold (UK). ISBN 0-7131-2459-8.

- I.S. Grant; W.R. Phillips; Manchester Physics (2008). Electromagnetism (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9. https://archive.org/details/electromagnetism0000gran.

- D.J. Griffiths (2007). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Pearson Education, Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-81-7758-293-2.

Further reading

- L.H. Greenberg (1978). Physics with Modern Applications. Holt-Saunders International W.B. Saunders and Co. ISBN 0-7216-4247-0. https://archive.org/details/physicswithmoder0000gree.

- J.B. Marion; W.F. Hornyak (1984). Principles of Physics. Holt-Saunders International Saunders College. ISBN 4-8337-0195-2.

- A. Beiser (1987). Concepts of Modern Physics (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill (International). ISBN 0-07-100144-1.

- H.D. Young; R.A. Freedman (2008). University Physics – With Modern Physics (12th ed.). Addison-Wesley (Pearson International). ISBN 978-0-321-50130-1.