Chemistry:Miraculin

| Miraculin glycoprotein | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

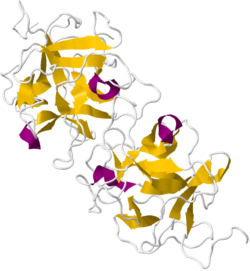

Crystallographic structure of a dimeric miraculin-like protein from seeds of Murraya koenigii.[1] | |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | MIRA_RICDU | ||||||

| PDB | 3IIR (ECOD) | ||||||

| UniProt | P13087 | ||||||

| |||||||

Miraculin itself does not taste sweet. When taste buds are exposed to miraculin, the protein binds to the sweetness receptors. This causes normally sour-tasting acidic foods, such as citrus, to be perceived as sweet.[2][3] The effect can last for one or two hours.[4][5]

History

The sweetening properties of Synsepalum dulcificum berries were first noted by des Marchais during expeditions to West Africa in the 18th century.[6] The term miraculin derived from experiments to isolate and purify the active glycoprotein that gave the berries their sweetening effects, results that were published simultaneously by Japanese and Dutch scientists working independently in the 1960s (the Dutch team called the glycoprotein mieraculin).[7][8] The word miraculin was in common use by the mid-1970s.[9][10][11]

Glycoprotein structure

Miraculin was first sequenced in 1989 and was found to be a 24.6 kilodalton[2] glycoprotein consisting of 191 amino acids[12] and 13.9% by weight of various sugars.[2]

SIGNAL (29) MKELTMLSLS FFFVSALLAA AANPLLSAA 1–50 DSAPNPVLDI DGEKLRTGTN YYIVPVLRDH GGGLTVSATT PNGTFVCPPR 51–100 VVQTRKEVDH DRPLAFFPEN PKEDVVRVST DLNINFSAFM PNPGPETISS 101–150 WCRWTSSTVW RLDKYDESTG QYFVTIGGVK FKIEEFCGSG FYKLVFCPTV 151–191 CGSCKVKCGD VGIYIDQKGR GRRLALSDKP FAFEFNKTVY F Amino acids sequence of glycoprotein miraculin unit adapted from Swiss-Prot biological database of protein sequences.[13]

The sugars consist of a total of 3.4 kDa, composed of a molar ratio of glucosamine (31%), mannose (30%), fucose (22%), xylose (10%), and galactose (7%).[2]

The native state of miraculin is a tetramer consisting of two dimers, each held together by a disulfide bridge.[14] Both tetramer miraculin and native dimer miraculin in its crude state have the taste-modifying activity of turning sour tastes into sweet tastes.[15] Miraculin belongs to the Kunitz STI protease inhibitor family.

Sweetness properties

Miraculin, unlike curculin (another taste-modifying agent),[16] is not sweet by itself, but it can change the perception of sourness to sweetness, even for a long period after consumption.[4] The duration and intensity of the sweetness-modifying effect depends on various factors, such as miraculin concentration, duration of contact of the miraculin with the tongue, and acid concentration.[3][4] Miraculin reaches its maximum sweetness with a solution containing at least 4*10−7 mol/L miraculin, which is held in the mouth for about 3 minutes. Maximum is equivalent in sweetness to a 0.4 mol/L solution of sucrose.[17] Miraculin degrades permanently via denaturation at high temperatures, at pH below 3 or above 12.[18]

Although the detailed mechanism of the taste-inducing behavior is unknown, it appears the sweet receptors are activated by acids which are related to sourness, an effect remaining until the taste buds perceive a neutral pH.[3][4] Sweeteners are perceived by the human sweet taste receptor, hT1R2-hT1R3, which belongs to G protein-coupled receptors,[4] modified by the two histidine residues (i.e. His30 and His60) which participate in the taste-modifying behavior.[19] One site maintains the attachment of the protein to the membranes while the other (with attached xylose or arabinose) activates the sweet receptor membrane in acid solutions.[14]

As a sweetener

As miraculin is a readily soluble protein and relatively heat stable, it is a potential sweetener in acidic food, such as soft drinks. While attempts to express it in yeast and tobacco plants have failed, researchers have succeeded in preparing genetically modified E. coli bacteria that express miraculin.[20] Lettuce and tomato have also been used for mass production of miraculin.[21][22]

The use of miraculin as a food additive was denied in 1974 by the United States Food and Drug Administration.[23] Since 2011, the FDA has imposed a ban on importing Synsepalum dulcificum (specifying 'miraculin') from its origin in Taiwan, declaring it as an "illegal undeclared sweetener".[24] The ban does not apply to the use of manufactured miraculin in dietary supplements.[25][26] Miraculin has a novel food status in the European Union.[27] It is approved in Japan as a safe food additive, according to the List of Existing Food Additives published by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (published by the Japan External Trade Organization).

See also

References

- ↑ PDB: 3IIR; "Cloning, sequence analysis and crystal structure determination of a miraculin-like protein from Murraya koenigii". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 494 (1): 15–22. February 2010. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2009.11.008. PMID 19914199.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedjbc-263-23-11536 - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Intracellular acidification is required for full activation of the sweet taste receptor by miraculin". Scientific Reports 6: 22807. March 2016. doi:10.1038/srep22807. PMID 26960429. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...622807S.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Human sweet taste receptor mediates acid-induced sweetness of miraculin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (40): 16819–24. October 2011. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016644108. PMID 21949380. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..10816819K.

- ↑ "The clinical effects of Synsepalum dulcificum: a review". Journal of Medicinal Food 17 (11): 1165–9. November 2014. doi:10.1089/jmf.2013.3084. PMID 25314134.

- ↑ "The miracle berry and miraculin: A review". WordPress. 27 July 2014. https://miracleberryandmiraculin.wordpress.com/.

- ↑ "Taste-modifying protein from miracle fruit". Science 161 (3847): 1241–3. September 1968. doi:10.1126/science.161.3847.1241. PMID 5673432. Bibcode: 1968Sci...161.1241K.

- ↑ "Mieraculin, the sweetness-inducing protein from miracle fruit". Nature 220 (5165): 373–4. October 1968. doi:10.1038/220373a0. PMID 5684879. Bibcode: 1968Natur.220..373B.

- ↑ "Chemostimulatory protein: a new type of taste stimulus". Science 181 (4094): 32–5. July 1973. doi:10.1126/science.181.4094.32. PMID 4714290. Bibcode: 1973Sci...181...32C.

- ↑ "Purification and some properties of miraculin, a glycoprotein from Synsepalum dulcificum which provokes sweetness and blocks sourness". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 22 (4): 595–601. 1974. doi:10.1021/jf60194a033. PMID 4840911.

- ↑ "[Physiology of smell and taste]". Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 210 (1): 43–65. 1975. doi:10.1007/bf00453707. PMID 233846.

- ↑ "Complete amino acid sequence and structure characterization of the taste-modifying protein, miraculin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 264 (12): 6655–9. April 1989. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83477-9. PMID 2708331. http://www.jbc.org/cgi/reprint/264/12/6655. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ↑ UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database entry P13087

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Characteristics of antisweet substances, sweet proteins, and sweetness-inducing proteins". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 32 (3): 231–52. 1992. doi:10.1080/10408399209527598. PMID 1418601.

- ↑ "Determination of disulfide array and subunit structure of taste-modifying protein, miraculin". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology 1079 (3): 303–7. September 1991. doi:10.1016/0167-4838(91)90073-9. PMID 1911854.

- ↑ "Curculin exhibits sweet-tasting and taste-modifying activities through its distinct molecular surfaces". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (46): 33252–6. November 2007. doi:10.1074/jbc.C700174200. PMID 17895249.

- ↑ Sweeteners: pharmacology, biotechnology, and applications. 2018. pp. 169. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-27027-2_17. ISBN 9783319270272. OCLC 1019806685.

- ↑ Mangla, B; Kohli, K (2018). "Pharmaceutical and therapeutic potential of miraculin and miracle berry". Tropical Journal of Natural Product Research 2 (1): 12–17. doi:10.26538/tjnpr/v2i1.3. ISSN 2616-0684.

- ↑ "Microbial production of sensory-active miraculin". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 360 (2): 407–11. August 2007. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.064. PMID 17592723.

- ↑ "Functional expression of miraculin, a taste-modifying protein in Escherichia coli". Journal of Biochemistry 145 (4): 445–50. April 2009. doi:10.1093/jb/mvn184. PMID 19122203.

- ↑ "Functional expression of the taste-modifying protein, miraculin, in transgenic lettuce". FEBS Letters 580 (2): 620–6. January 2006. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.080. PMID 16406368.

- ↑ "Molecular breeding of tomato lines for mass production of miraculin in a plant factory". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 58 (17): 9505–10. September 2010. doi:10.1021/jf101874b. PMID 20695489.

- ↑ Gollner, Adam Leith (31 March 2009). The Fruit Hunters: A Story of Nature, Adventure, Commerce and Obsession. Anchor Canada. ISBN 978-0385662680.

- ↑ "Synsepalum dulcificum Import Alert 45-07; Taiwan". US Food and Drug Administration. 5 February 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cms_ia/importalert_120.html.

- ↑ Hieggelke, Brian (2013-04-18). "Sugar Freedom: Chef Homaro Cantu and his Magnificent Miracle Berry Obsession". NewCity Communications Inc.. https://resto.newcity.com/2013/04/18/sugar-freedom-chef-homaro-cantu-and-his-magnificent-miracle-berry-obsession/.

- ↑ Cox, David (2014-05-29). "The 'Miracle' Berry That Could Replace Sugar". The Atlantic Monthly Group. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/05/can-miraculin-solve-the-global-obesity-epidemic/371657/.

- ↑ "Novel Food Catalogue". https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/novel_food/catalogue/search/public/?event=home&seqfce=464&ascii=S.

|