Chemistry:Isoleucine

skeletal formula of L-isoleucine

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Isoleucine

| |||

| Other names

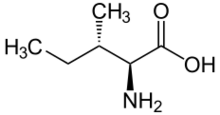

(2S,3S)-2-amino-3-methylpentanoic acid

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H13NO2 | |||

| Molar mass | 131.175 g·mol−1 | ||

| −84.9·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

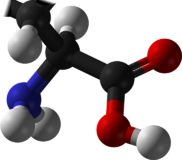

Isoleucine (symbol Ile or I)[1] is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH+3 form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− form under biological conditions), and a hydrocarbon side chain with a branch (a central carbon atom bound to three other carbon atoms). It is classified as a non-polar, uncharged (at physiological pH), branched-chain, aliphatic amino acid. It is essential in humans, meaning the body cannot synthesize it. Essential amino acids are necessary in the human diet. In plants isoleucine can be synthesized from threonine and methionine.[2] In plants and bacteria, isoleucine is synthesized from pyruvate employing leucine biosynthesis enzymes.[3] It is encoded by the codons AUU, AUC, and AUA.

Metabolism

Biosynthesis

In plants and microorganisms, isoleucine is synthesized from pyruvate and alpha-ketobutyrate. This pathway is not present in humans. Enzymes involved in this biosynthesis include:[4]

- Acetolactate synthase (also known as acetohydroxy acid synthase)

- Acetohydroxy acid isomeroreductase

- Dihydroxyacid dehydratase

- Valine aminotransferase

Catabolism

Isoleucine is both a glucogenic and a ketogenic amino acid.[4] After transamination with alpha-ketoglutarate, the carbon skeleton is oxidised and split into propionyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA. Propionyl-CoA is converted into succinyl-CoA, a TCA cycle intermediate which can be converted into oxaloacetate for gluconeogenesis (hence glucogenic). In mammals acetyl-CoA cannot be converted to carbohydrate but can be either fed into the TCA cycle by condensing with oxaloacetate to form citrate or used in the synthesis of ketone bodies (hence ketogenic) or fatty acids.[5]

Metabolic diseases

The degradation of isoleucine is impaired in the following metabolic diseases:

- Combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria (CMAMMA)

- Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD)

- Methylmalonic acidemia

- Propionic acidemia

Insulin resistance

Isoleucine, like other branched-chain amino acids, is associated with insulin resistance: higher levels of isoleucine are observed in the blood of diabetic mice, rats, and humans.[6] In diet-induced obese and insulin resistant mice, a diet with decreased levels of isoleucine (with or without the other branched-chain amino acids) results in reduced adiposity and improved insulin sensitivity.[7][8] Reduced dietary levels of isoleucine are required for the beneficial metabolic effects of a low protein diet.[8] In humans, a protein restricted diet lowers blood levels of isoleucine and decreases fasting blood glucose levels.[9] Mice fed a low isoleucine diet are leaner, live longer, and are less frail.[10] In humans, higher dietary levels of isoleucine are associated with greater body mass index.[8]

Functions and requirement

The Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) of the U.S. Institute of Medicine has set Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for essential amino acids in 2002. For adults 19 years and older, 19 mg of isoleucine/kg body weight is required daily.[11]

Beside its biological role as a nutrient, isoleucine also participates in regulation of glucose metabolism.[5] Isoleucine is an essential component of many proteins. As an essential amino acid, isoleucine must be ingested or protein production in the cell will be disrupted. Fetal hemoglobin is one of the many proteins that require isoleucine.[12] Isoleucine is present in the gamma chain of fetal hemoglobin and must be present for the protein to form. [12]

Genetic diseases can change the consumption requirements of isoleucine. Amino acids cannot be stored in the body. Buildup of excess amino acids will cause a buildup of toxic molecules so, humans have many pathways to degrade each amino acid when the need for protein synthesis has been met.[13] Mutations in isoleucine-degrading enzymes can lead to dangerous buildup of isoleucine and it's toxic derivative. One example is maple syrup urine disease (MSUD), a disorder that leaves people unable to breakdown isoleucine, valine, and leucine.[14] People with MSUD manage their disease by a reduced intake of all three of those amino acids alongside drugs that help excrete built-up toxins. [15]

Many animals and plants are dietary sources of isoleucine as a component of proteins.[5] Foods that have high amounts of isoleucine include eggs, soy protein, seaweed, turkey, chicken, lamb, cheese, and fish.

Synthesis

Routes to isoleucine are numerous. One common multistep procedure starts from 2-bromobutane and diethylmalonate.[16] Synthetic isoleucine was first reported in 1905 by French chemists Bouveault and Locquin.[17]

Discovery

German chemist Felix Ehrlich discovered isoleucine while studying the composition of beet-sugar molasses 1903.[18] In 1907 Ehrlich carried out further studies on fibrin, egg albumin, gluten, and beef muscle in 1907. These studies verified the natural composition of isoleucine.[18] Ehrlich published his own synthesis of isoleucine in 1908. [19]

See also

- Alloisoleucine, the diasteromer of isoleucine

References

- ↑ "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). Nomenclature and symbolism for amino acids and peptides. Recommendations 1983". The Biochemical Journal 219 (2): 345–373. April 1984. doi:10.1042/bj2190345. PMID 6743224.

- ↑ "Interdependence of threonine, methionine and isoleucine metabolism in plants: accumulation and transcriptional regulation under abiotic stress". Amino Acids 39 (4): 933–947. October 2010. doi:10.1007/s00726-010-0505-7. PMID 20186554.

- ↑ "Pathway for isoleucine formation form pyruvate by leucine biosynthetic enzymes in leucine-accumulating isoleucine revertants of Serratia marcescens". Journal of Biochemistry 82 (1): 95–103. July 1977. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131698. PMID 142769.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lehninger principles of biochemistry. (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. 2000. ISBN 1-57259-153-6. OCLC 42619569. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/42619569.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Branched chain amino acids in clinical nutrition. 1. New York, New York: Humana. 2015. ISBN 978-1-4939-1923-9. OCLC 898999904.

- ↑ "Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology 10 (12): 723–736. December 2014. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2014.171. PMID 25287287.

- ↑ "Restoration of metabolic health by decreased consumption of branched-chain amino acids". The Journal of Physiology 596 (4): 623–645. February 2018. doi:10.1113/JP275075. PMID 29266268.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "The adverse metabolic effects of branched-chain amino acids are mediated by isoleucine and valine". Cell Metabolism 33 (5): 905–922.e6. May 2021. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2021.03.025. PMID 33887198.

- ↑ "Decreased Consumption of Branched-Chain Amino Acids Improves Metabolic Health". Cell Reports 16 (2): 520–530. July 2016. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.092. PMID 27346343.

- ↑ "Dietary restriction of isoleucine increases healthspan and lifespan of genetically heterogeneous mice". Cell Metabolism 35 (11): 1976–1995.e6. November 2023. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2023.10.005. PMID 37939658.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine. Panel on Macronutrients, Institute of Medicine. Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes (2005). Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. ISBN 0-309-08537-3. OCLC 57373786. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/57373786.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Inhibition of synthesis of fetal hemoglobin by an isoleucine analogue". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 46 (11): 1778–1784. November 1967. doi:10.1172/JCI105668. PMID 4964832.

- ↑ "Inborn errors of isoleucine degradation: a review". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 89 (4): 289–299. December 2006. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.07.010. PMID 16950638.

- ↑ "Maple Syrup Urine Disease". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557773/. Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ↑ "Phenylbutyrate therapy for maple syrup urine disease". Human Molecular Genetics 20 (4): 631–640. February 2011. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq507. PMID 21098507.

- ↑ "dl-Isoleucine" (in en). Organic Syntheses 21: 60. 1941. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.021.0060. ISSN 0078-6209. https://doi.org/10.15227/orgsyn.021.0060.

- ↑ "Sur la synthése d'une nouvelle leucine". Compt. Rend. (141): 115–117. 1905.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "The History of the Discovery of the Amino Acids." (in en). Chemical Reviews 9 (2): 169–318. October 1931. doi:10.1021/cr60033a001. ISSN 0009-2665.

- ↑ "Über eine Synthese des Isoleucins". Chemische Berichte 41 (1): 1453–1458. 1908. doi:10.1002/cber.190804101266. ISSN 0365-9496. https://zenodo.org/record/2512647.

External links

|