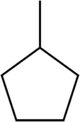

Chemistry:Methylcyclopentane

From HandWiki

|

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Methylcyclopentane | |||

| Identifiers | |||

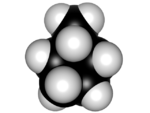

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| EC Number |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2298 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H12 | |||

| Molar mass | 84.162 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Density | 0.749 g/cm3[1] | ||

| Melting point | −142.4 °C (−224.3 °F; 130.8 K)[1] | ||

| Boiling point | 71.8 °C (161.2 °F; 344.9 K)[1] | ||

| Insoluble | |||

| -70.17·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | flammable | ||

| Flash point | −4 °C (25 °F; 269 K) | ||

| 260 °C (500 °F; 533 K) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Tracking categories (test):

Methylcyclopentane is an organic compound with the chemical formula CH3C5H9. It is a colourless, flammable liquid with a faint odor. It is a component of the naphthene fraction of petroleum. It usually is obtained as a mixture with cyclohexane. It is mainly converted in naphthene reformers to benzene.[2] The C6 core of methylcyclopentane is not perfectly planar and can pucker to alleviate stress in its structure.[3]

History

In 1895, Nikolai Kischner discovered that methylcyclopentane was the reaction product of hydrogenation of benzene using hydriodic acid. Prior to that, several chemists (such as Marcellin Berthelot in 1867,[4][5] and Adolf von Baeyer in 1870[6]) had tried and failed to synthesize cyclohexane using this method.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Lide, David. R, ed (2009). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (89th ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6679-1. https://archive.org/details/crchandbookofche00davi.

- ↑ M. Larry Campbell (2012). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_209.pub2.

- ↑ Carey, Francis; Giuliano, Robert (2014). "3". Organic Chemistry (9 ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 97–131. ISBN 978-0073402741.

- ↑ Bertholet (1867). "Nouvelles applications des méthodes de réduction en chimie organique" (in fr). Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Paris series 2 (7): 53–65. https://books.google.com/books?id=YVgSAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA53.

- ↑ Bertholet (1868). "Méthode universelle pour réduire et saturer d'hydrogène les composés organiques" (in fr). Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Paris series 2 (9): 8–31. https://books.google.com/books?id=r1sSAAAAYAAJ&q=Bertholet&pg=PA17. "En effet, la benzine, chauffée à 280° pendant 24 heures avec 80 fois son poids d'une solution aqueuse saturée à froid d'acide iodhydrique, se change à peu près entièrement en hydrure d'hexylène, C12H14, en fixant 4 fois son volume d'hydrogène: C12H6 + 4H2 = C12H14 … Le nouveau carbure formé par la benzine est un corps unique et défini: il bout à 69°, et offre toutes les propriétés et la composition de l'hydrure d'hexylène extrait des pétroles.".

- ↑ Adolf Baeyer (1870). "Ueber die Reduction aromatischer Kohlenwasserstoffe durch Jodphosphonium". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie 55: 266–281. https://books.google.com/books?id=RJU8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA266. "Bei der Reduction mit Natriumamalgam oder Jodphosphonium addiren sich im höchsten Falle sechs Atome Wasserstoff, und es entstehen Abkömmlinge, die sich von einem Kohlenwasserstoff C6H12 ableiten. Dieser Kohlenwasserstoff ist aller Wahrscheinlichkeit nach ein geschlossener Ring, da seine Derivate, das Hexahydromesitylen und Hexahydromellithsäure, mit Leichtigkeit wieder in Benzolabkömmlinge übergeführt werden können.".

|