Astronomy:Lunar Laser Ranging experiment

Lunar Laser Ranging (LLR) is the practice of measuring the distance between the surfaces of the Earth and the Moon using laser ranging. The distance can be calculated from the round-trip time of laser light pulses travelling at the speed of light, which are reflected back to Earth by the Moon's surface or by one of five retroreflectors installed on the Moon during the Apollo program (11, 14, and 15) and Lunokhod 1 and 2 missions.[1]

Although it is possible to reflect light or radio waves directly from the Moon's surface (a process known as EME), a much more precise range measurement can be made using retroreflectors, since because of their small size, the temporal spread in the reflected signal is much smaller.

A review of Lunar Laser Ranging is available.[2]

Laser ranging measurements can also be made with retroreflectors installed on Moon-orbiting satellites such as the LRO.[3][4]

History

The first successful lunar ranging tests were carried out in 1962 when Louis Smullin and Giorgio Fiocco from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology succeeded in observing laser pulses reflected from the Moon's surface using a laser with a 50J 0.5 millisecond pulse length.[5] Similar measurements were obtained later the same year by a Soviet team at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory using a Q-switched ruby laser.[6]

Shortly thereafter, Princeton University graduate student James Faller proposed placing optical reflectors on the Moon to improve the accuracy of the measurements.[7] This was achieved following the installation of a retroreflector array on July 21, 1969 by the crew of Apollo 11. Two more retroreflector arrays were left by the Apollo 14 and Apollo 15 missions. Successful lunar laser range measurements to the retroreflectors were first reported on Aug. 1, 1969 by the 3.1 m telescope at Lick Observatory.[7] Observations from Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratories Lunar Ranging Observatory in Arizona, the Pic du Midi Observatory in France, the Tokyo Astronomical Observatory, and McDonald Observatory in Texas soon followed.

The uncrewed Soviet Lunokhod 1 and Lunokhod 2 rovers carried smaller arrays. Reflected signals were initially received from Lunokhod 1 by the Soviet Union up to 1974, but not by western observatories that did not have precise information about location. In 2010 NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter located the Lunokhod 1 rover on images and in April 2010 a team from University of California ranged the array.[8] Lunokhod 2's array continues to return signals to Earth.[9] The Lunokhod arrays suffer from decreased performance in direct sunlight—a factor considered in reflector placement during the Apollo missions.[10]

The Apollo 15 array is three times the size of the arrays left by the two earlier Apollo missions. Its size made it the target of three-quarters of the sample measurements taken in the first 25 years of the experiment. Improvements in technology since then have resulted in greater use of the smaller arrays, by sites such as the Côte d'Azur Observatory in Nice, France; and the Apache Point Observatory Lunar Laser-ranging Operation (APOLLO) at the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico.

In the 2010s several new retroreflectors were planned. The MoonLIGHT reflector, which was to be placed by the private MX-1E lander, was designed to increase measurement accuracy up to 100 times over existing systems.[11][12][13] MX-1E was set to launch in July 2020,[14] however, as of February 2020, the launch of the MX-1E has been canceled.[15] MoonLIGHT will be launched in early 2024 with a Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) mission.[16]

Principle

The distance to the Moon is calculated approximately using the equation: distance = (speed of light × duration of delay due to reflection) / 2. Since the speed of light is a defined constant, conversion between distance and time of flight can be made without ambiguity.

To compute the lunar distance precisely, many factors must be considered in addition to the round-trip time of about 2.5 seconds. These factors include the location of the Moon in the sky, the relative motion of Earth and the Moon, Earth's rotation, lunar libration, polar motion, weather, speed of light in various parts of air, propagation delay through Earth's atmosphere, the location of the observing station and its motion due to crustal motion and tides, and relativistic effects.[18][19] The distance continually changes for a number of reasons, but averages 385,000.6 km (239,228.3 mi) between the center of the Earth and the center of the Moon.[20] The orbits of the Moon and planets are integrated numerically along with the orientation of the Moon called physical Libration.[21]

At the Moon's surface, the beam is about 6.5 kilometers (4.0 mi) wide[22][lower-roman 1] and scientists liken the task of aiming the beam to using a rifle to hit a moving dime 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) away. The reflected light is too weak to see with the human eye. Out of 3.075*10^17 photons (data taken from the apollo website, section "Staggering Odds") aimed at the reflector, only one is received back on Earth, even under good conditions.[23] They can be identified as originating from the laser because the laser is highly monochromatic.

As of 2009, the distance to the Moon can be measured with millimeter precision.[24] In a relative sense, this is one of the most precise distance measurements ever made, and is equivalent in accuracy to determining the distance between Los Angeles and New York to within the width of a human hair.

List of retroreflectors

List of observatories

The table below presents a list of active and inactive Lunar Laser Ranging stations on Earth.[20][25]

| Observatory | Project | Operating timespan | Telescope | Laser | Range accuracy | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McDonald Observatory, Texas, US | MLRS | 1969–1985

1985–2013 |

2.7 m | 694 nm, 7 J

532 nm, 200 ps, 150 mJ |

[26] | |

| Crimean Astrophysical Observatory (CrAO), USSR | 1974, 1982–1984 | 694 nm | 3.0–0.6 m | [27] | ||

| Côte d'Azur Observatory (OCA), Grasse, France | MeO | 1984–1986

1986–2010 2010–present (2021) |

694 nm

532 nm, 70 ps, 75 mJ 532/1064 nm |

[20][28] | ||

| Haleakala Observatory, Hawaii, US | LURE | 1984–1990 | 532 nm, 200 ps, 140 mJ | 2.0 cm | [20][29] | |

| Matera Laser Ranging Observatory (MLRO), Italy | 2003–present (2021) | 532 nm | ||||

| Apache Point Observatory, New Mexico, US | APOLLO | 2006–2020 | 532 nm, 100 ps, 115 mJ | 1.1 mm | [20] | |

| Geodetic Observatory Wettzell, Germany | WLRS | 2018–present (2021) | 1064 nm, 10 ps, 75 mJ | [30] | ||

| Yunnan Astronomical Observatory, Kunming, China | 2018 | 1.2 m | 532 nm, 10 ns, 3 J | meter level | [31] |

Data analysis

The Lunar Laser Ranging data is collected in order to extract numerical values for a number of parameters. Analyzing the range data involves dynamics, terrestrial geophysics, and lunar geophysics. The modeling problem involves two aspects: an accurate computation of the lunar orbit and lunar orientation, and an accurate model for the time of flight from an observing station to a retroreflector and back to the station. Modern Lunar Laser Ranging data can be fit with a 1 cm weighted rms residual.

- The center of Earth to center of Moon distance is computed by a program that numerically integrates the lunar and planetary orbits accounting for the gravitational attraction of the Sun, planets, and a selection of asteroids.[32][21]

- The same program integrates the 3-axis orientation of the Moon called physical Libration.

The range model includes[32][33]

- The position of the ranging station accounting for motion due to plate tectonics, Earth rotation, precession, nutation, and polar motion.

- Tides in the solid Earth and seasonal motion of the solid Earth with respect to its center of mass.

- Relativistic transformation of time and space coordinates from a frame moving with the station to a frame fixed with respect to the solar system center of mass. Lorentz contraction of the Earth is part of this transformation.

- Delay in the Earth’s atmosphere.

- Relativistic delay due to the gravity fields of the Sun, Earth, and Moon.

- The position of the retroreflector accounting for orientation of the Moon and solid-body tides.

- Lorentz contraction of the Moon.

- Thermal expansion and contraction of the retroreflector mounts.

For the terrestrial model, the IERS Conventions (2010) is a source of detailed information.[34]

Results

Lunar laser ranging measurement data is available from the Paris Observatory Lunar Analysis Center,[35] the International Laser Ranging Service archives,[36][37] and the active stations. Some of the findings of this long-term experiment are:[20]

Properties of the Moon

- The distance to the Moon can be measured with millimeter precision.[24]

- The Moon is spiraling away from Earth at a rate of 3.8 cm/year.[22][38] This rate has been described as anomalously high.[39]

- The fluid core of the Moon was detected from the effects of core/mantle boundary dissipation.[40]

- The Moon has free physical librations that require one or more stimulating mechanisms.[41]

- Tidal dissipation in the Moon depends on tidal frequency.[42]

- The Moon probably has a liquid core of about 20% of the Moon's radius.[9] The radius of the lunar core-mantle boundary is determined as 381±12 km.[43]

- The polar flattening of the lunar core-mantle boundary is determined as (2.2±0.6)×10−4.[43]

- The free core nutation of the Moon is determined as 367±100 yr.[43]

- Accurate locations for retroreflectors serve as reference points visible to orbiting spacecraft.[44]

Gravitational physics

- Einstein's theory of gravity (the general theory of relativity) predicts the Moon's orbit to within the accuracy of the laser ranging measurements.[9][45]

- Gauge freedom plays a major role in a correct physical interpretation of the relativistic effects in the Earth-Moon system observed with LLR technique.[46]

- The likelihood of any Nordtvedt effect (a hypothetical differential acceleration of the Moon and Earth towards the Sun caused by their different degrees of compactness) has been ruled out to high precision,[47][45][48] strongly supporting the strong equivalence principle.

- The universal force of gravity is very stable. The experiments have constrained the change in Newton's gravitational constant G to a factor of (2±7)×10−13 per year.[49]

Gallery

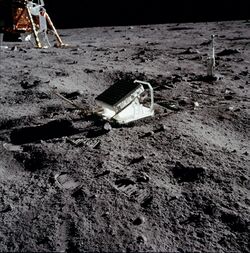

Apollo 14 Lunar Ranging Retro Reflector (LRRR)

APOLLO collaboration photon pulse return times

Laser ranging facility at Wettzell fundamental station, Bavaria, Germany

Laser Ranging at Goddard Space Flight Center

See also

- Carroll Alley (first principal investigator of the Apollo Lunar Laser Ranging team)

- Lidar

- Lunar distance

- Satellite laser ranging

- Space geodesy

- Third-party evidence for Apollo Moon landings

- List of artificial objects on the Moon

References

- ↑ During the round-trip time, an Earth observer will have moved by around 1 km (depending on their latitude). This has been presented, incorrectly, as a 'disproof' of the ranging experiment, the claim being that the beam to such a small reflector cannot hit such a moving target. However the size of the beam is far larger than any movement, especially for the returned beam.

- ↑ Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G. (1999). "Determination of the lunar orbital and rotational parameters and of the ecliptic reference system orientation from LLR measurements and IERS data". Astronomy and Astrophysics 343: 624–633. Bibcode: 1999A&A...343..624C.

- ↑ Müller, Jürgen; Murphy, Thomas W.; Schreiber, Ulrich; Shelus, Peter J.; Torre, Jean-Marie; Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H.; Bouquillon, Sebastien et al. (2019). "Lunar Laser Ranging: a tool for general relativity, lunar geophysics and Earth science" (in en). Journal of Geodesy 93 (11): 2195–2210. doi:10.1007/s00190-019-01296-0. ISSN 1432-1394. Bibcode: 2019JGeod..93.2195M. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-019-01296-0.

- ↑ Mazarico, Erwan; Sun, Xiaoli; Torre, Jean-Marie; Courde, Clément; Chabé, Julien; Aimar, Mourad; Mariey, Hervé; Maurice, Nicolas et al. (2020-08-06). "First two-way laser ranging to a lunar orbiter: infrared observations from the Grasse station to LRO's retro-reflector array". Earth, Planets and Space 72 (1): 113. doi:10.1186/s40623-020-01243-w. ISSN 1880-5981. Bibcode: 2020EP&S...72..113M.

- ↑ Kornei, Katherine (2020-08-15). "How Do You Solve a Moon Mystery? Fire a Laser at It" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/15/science/moon-lasers-dust.html.

- ↑ Smullin, Louis D.; Fiocco, Giorgio (1962). "Optical Echoes from the Moon". Nature 194 (4835): 1267. doi:10.1038/1941267a0. Bibcode: 1962Natur.194.1267S.

- ↑ Bender, P. L. (1973). "The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment: Accurate ranges have given a large improvement in the lunar orbit and new selenophysical information". Science 182 (4109): 229–238. doi:10.1126/science.182.4109.229. PMID 17749298. Bibcode: 1973Sci...182..229B. http://www.physics.ucsd.edu/~tmurphy/apollo/doc/Bender.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Newman, Michael E. (2017-09-26). "To the Moon and Back … in 2.5 Seconds" (in en). NIST. https://www.nist.gov/nist-time-capsule/any-object-any-need-call-nist/moon-and-back-25-seconds. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- ↑ McDonald, K. (26 April 2010). "UC San Diego Physicists Locate Long Lost Soviet Reflector on Moon". University of California, San Diego. http://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu/newsrel/science/04-26SovietReflector.asp.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Williams, James G.; Dickey, Jean O. (2002). "Lunar Geophysics, Geodesy, and Dynamics". 13th International Workshop on Laser Ranging. 7–11 October 2002. Washington, D. C.. https://ilrs.cddis.eosdis.nasa.gov/docs/williams_lw13.pdf.

- ↑ "It's Not Just The Astronauts That Are Getting Older". Universe Today. 10 March 2010. http://www.universetoday.com/59310/its-not-just-the-astronauts-that-are-getting-older/.

- ↑ Currie, Douglas; Dell'Agnello, Simone; Delle Monache, Giovanni (April–May 2011). "A Lunar Laser Ranging Retroreflector Array for the 21st Century". Acta Astronautica 68 (7–8): 667–680. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2010.09.001. Bibcode: 2011AcAau..68..667C.

- ↑ Tune, Lee (10 June 2015). "UMD, Italy & MoonEx Join to Put New Laser-Reflecting Arrays on Moon". UMD Right Now (University of Maryland). https://umdrightnow.umd.edu/news/umd-italy-moonex-join-put-new-laser-reflecting-arrays-moon.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan (12 July 2017). "Moon Express unveils its roadmap for giant leaps to the lunar surface ... and back again". GeekWire. https://www.geekwire.com/2017/moon-express-unveils-roadmap-giant-leaps-lunar-surface-back/.

- ↑ Moon Express Lunar Scout (MX-1E), RocketLaunch.Live, https://www.rocketlaunch.live/launch/lunar-scout, retrieved 27 July 2019

- ↑ "MX-1E 1, 2, 3". https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/mx-1e.htm.

- ↑ "NASA Payloads for (CLPS PRISM) CP-11". https://science.nasa.gov/lunar-discovery/deliveries/cp-11.

- ↑ "Was Galileo Wrong?". NASA. 6 May 2004. http://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2004/06may_lunarranging/.

- ↑ Seeber, Günter (2003). Satellite Geodesy (2nd ed.). de Gruyter. p. 439. ISBN 978-3-11-017549-3. OCLC 52258226. https://archive.org/details/satellitegeodesy00seeb.

- ↑ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2020). "The JPL Lunar Laser range model 2020". https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/ftp/eph/planets/ioms/.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Murphy, T. W. (2013). "Lunar laser ranging: the millimeter challenge". Reports on Progress in Physics 76 (7): 2. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/76/7/076901. PMID 23764926. Bibcode: 2013RPPh...76g6901M. http://physics.ucsd.edu/~tmurphy/papers/rop-llr.pdf.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Park, Ryan S.; Folkner, William M.; Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2021). "The JPL Planetary and Lunar Ephemerides DE440 and DE441" (in en). The Astronomical Journal 161 (3): 105. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abd414. ISSN 1538-3881. Bibcode: 2021AJ....161..105P.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Espenek, F. (August 1994). "NASA – Accuracy of Eclipse Predictions". NASA/GSFC. http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEhelp/ApolloLaser.html.

- ↑ Merkowitz, Stephen M. (2010-11-02). "Tests of Gravity Using Lunar Laser Ranging" (in en). Living Reviews in Relativity 13 (1): 7. doi:10.12942/lrr-2010-7. ISSN 1433-8351. PMID 28163616. Bibcode: 2010LRR....13....7M.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Battat, J. B. R.; Murphy, T. W.; Adelberger, E. G. et al. (January 2009). "The Apache Point Observatory Lunar Laser-ranging Operation (APOLLO): Two Years of Millimeter-Precision Measurements of the Earth-Moon Range1". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 121 (875): 29–40. doi:10.1086/596748. Bibcode: 2009PASP..121...29B.

- ↑ Biskupek, Liliane; Müller, Jürgen; Torre, Jean-Marie (2021-02-03). "Benefit of New High-Precision LLR Data for the Determination of Relativistic Parameters" (in en). Universe 7 (2): 34. doi:10.3390/universe7020034. Bibcode: 2021Univ....7...34B.

- ↑ Bender, P. L.; Currie, D. G.; Dickey, R. H.; Eckhardt, D. H.; Faller, J. E.; Kaula, W. M.; Mulholland, J. D.; Plotkin, H. H. et al. (1973). "The Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment" (in en). Science 182 (4109): 229–238. doi:10.1126/science.182.4109.229. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17749298. Bibcode: 1973Sci...182..229B. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.182.4109.229.

- ↑ Yagudina (2018). "Processing and analysis of lunar laser ranging observations in Crimea in 1974-1984". http://iaaras.ru/en/library/paper/1943/.

- ↑ Chabé, Julien; Courde, Clément; Torre, Jean-Marie; Bouquillon, Sébastien; Bourgoin, Adrien; Aimar, Mourad; Albanèse, Dominique; Chauvineau, Bertrand et al. (2020). "Recent Progress in Lunar Laser Ranging at Grasse Laser Ranging Station" (in en). Earth and Space Science 7 (3): e2019EA000785. doi:10.1029/2019EA000785. ISSN 2333-5084. Bibcode: 2020E&SS....700785C.

- ↑ "Lure Observatory". 2002-01-29. http://koa.ifa.hawaii.edu/Lure/.

- ↑ Eckl, Johann J.; Schreiber, K. Ulrich; Schüler, Torben (2019-04-30). Domokos, Peter; James, Ralph B; Prochazka, Ivan et al.. eds. "Lunar laser ranging utilizing a highly efficient solid-state detector in the near-IR". Quantum Optics and Photon Counting 2019 (International Society for Optics and Photonics) 11027: 1102708. doi:10.1117/12.2521133. ISBN 9781510627208. Bibcode: 2019SPIE11027E..08E. https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/11027/1102708/Lunar-laser-ranging-utilizing-a-highly-efficient-solid-state-detector/10.1117/12.2521133.short.

- ↑ Li Yuqiang, 李语强; Fu Honglin, 伏红林; Li Rongwang, 李荣旺; Tang Rufeng, 汤儒峰; Li Zhulian, 李祝莲; Zhai Dongsheng, 翟东升; Zhang Haitao, 张海涛; Pi Xiaoyu, 皮晓宇 et al. (2019-01-27). "Research and Experiment of Lunar Laser Ranging in Yunnan Observatories". Chinese Journal of Lasers 46 (1): 0104004. doi:10.3788/CJL201946.0104004. http://www.opticsjournal.net/Articles/Abstract/zgjg/46/1/0104004.cshtml.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Pavlov, Dmitry A.; Williams, James G.; Suvorkin, Vladimir V. (2016). "Determining parameters of Moon's orbital and rotational motion from LLR observations using GRAIL and IERS-recommended models" (in en). Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 126 (1): 61–88. doi:10.1007/s10569-016-9712-1. ISSN 0923-2958. Bibcode: 2016CeMDA.126...61P. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10569-016-9712-1.

- ↑ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2020). "The JPL Lunar Laser range model 2020". https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/ftp/eph/planets/ioms/.

- ↑ "IERS - IERS Technical Notes - IERS Conventions (2010)". https://www.iers.org/IERS/EN/Publications/TechnicalNotes/tn36.html.

- ↑ "Lunar Laser Ranging Observations from 1969 to May 2013". SYRTE Paris Observatory. http://polac.obspm.fr/llrdatae.html.

- ↑ "International Laser Ranging Service". ftp://cddis.gsfc.nasa.gov/pub/slr/data/npt_crd/.

- ↑ "International Laser Ranging Service". ftp://edc.dgfi.tum.de/pub/slr/data/npt_crd/.

- ↑ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2016). "Secular tidal changes in lunar orbit and Earth rotation" (in en). Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 126 (1): 89–129. doi:10.1007/s10569-016-9702-3. ISSN 0923-2958. Bibcode: 2016CeMDA.126...89W. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10569-016-9702-3.

- ↑ Bills, B. G.; Ray, R. D. (1999). "Lunar Orbital Evolution: A Synthesis of Recent Results". Geophysical Research Letters 26 (19): 3045–3048. doi:10.1029/1999GL008348. Bibcode: 1999GeoRL..26.3045B.

- ↑ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H.; Yoder, Charles F.; Ratcliff, J. Todd; Dickey, Jean O. (2001). "Lunar rotational dissipation in solid body and molten core" (in en). Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 106 (E11): 27933–27968. doi:10.1029/2000JE001396. Bibcode: 2001JGR...10627933W.

- ↑ Rambaux, N.; Williams, J. G. (2011). "The Moon's physical librations and determination of their free modes". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 109 (1): 85–100. doi:10.1007/s10569-010-9314-2. Bibcode: 2011CeMDA.109...85R. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00588671/file/PEER_stage2_10.1007%252Fs10569-010-9314-2.pdf.

- ↑ Williams, James G.; Boggs, Dale H. (2016). "Secular tidal changes in lunar orbit and Earth rotation" (in en). Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 126 (1): 89–129. doi:10.1007/s10569-016-9702-3. ISSN 0923-2958. Bibcode: 2016CeMDA.126...89W. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10569-016-9702-3.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Viswanathan, V.; Rambaux, N.; Fienga, A.; Laskar, J.; Gastineau, M. (9 July 2019). "Observational Constraint on the Radius and Oblateness of the Lunar Core‐Mantle Boundary". Geophysical Research Letters 46 (13): 7295–7303. doi:10.1029/2019GL082677. Bibcode: 2019GeoRL..46.7295V.

- ↑ Wagner, R. V.; Nelson, D. M.; Plescia, J. B.; Robinson, M. S.; Speyerer, E. J.; Mazarico, E. (2017). "Coordinates of anthropogenic features on the Moon" (in en). Icarus 283: 92–103. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.05.011. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2017Icar..283...92W. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0019103516301518.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Williams, J. G.; Newhall, X. X.; Dickey, J. O. (1996). "Relativity parameters determined from lunar laser ranging". Physical Review D 53 (12): 6730–6739. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.53.6730. PMID 10019959. Bibcode: 1996PhRvD..53.6730W.

- ↑ Kopeikin, S.; Xie, Y. (2010). "Celestial reference frames and the gauge freedom in the post-Newtonian mechanics of the Earth–Moon system". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 108 (3): 245–263. doi:10.1007/s10569-010-9303-5. Bibcode: 2010CeMDA.108..245K.

- ↑ Adelberger, E. G.; Heckel, B. R.; Smith, G.; Su, Y.; Swanson, H. E. (1990). "Eötvös experiments, lunar ranging and the strong equivalence principle". Nature 347 (6290): 261–263. doi:10.1038/347261a0. Bibcode: 1990Natur.347..261A.

- ↑ Viswanathan, V; Fienga, A; Minazzoli, O; Bernus, L; Laskar, J; Gastineau, M (May 2018). "The new lunar ephemeris INPOP17a and its application to fundamental physics". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 476 (2): 1877–1888. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty096.

- ↑ Müller, J.; Biskupek, L. (2007). "Variations of the gravitational constant from lunar laser ranging data". Classical and Quantum Gravity 24 (17): 4533. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/24/17/017.

External links

- "Theory and Model for the New Generation of the Lunar Laser Ranging Data" by Sergei Kopeikin

- Apollo 15 Experiments - Laser Ranging Retroreflector by the Lunar and Planetary Institute

- "History of Laser Ranging and MLRS" by the University of Texas at Austin, Center for Space Research

- "Lunar Retroreflectors" by Tom Murphy

- Station de Télémétrie Laser-Lune in Grasse, France

- Lunar Laser Ranging from International Laser Ranging Service

- "UW researcher plans project to pin down moon's distance from Earth" by Vince Stricherz, UW Today, 14 January 2002

- "What Neil & Buzz Left on the Moon" by Science@NASA, 20 July 2004

- "Apollo 11 Experiment Still Returning Results" by Robin Lloyd, CNN, 21 July 1999

- "Shooting Lasers at the Moon: Hal Walker and the Lunar Retroreflector" by Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, YouTube, 20 Aug 2019