Kakutani fixed-point theorem

In mathematical analysis, the Kakutani fixed-point theorem is a fixed-point theorem for set-valued functions. It provides sufficient conditions for a set-valued function defined on a convex, compact subset of a Euclidean space to have a fixed point, i.e. a point which is mapped to a set containing it. The Kakutani fixed point theorem is a generalization of the Brouwer fixed point theorem. The Brouwer fixed point theorem is a fundamental result in topology which proves the existence of fixed points for continuous functions defined on compact, convex subsets of Euclidean spaces. Kakutani's theorem extends this to set-valued functions.

The theorem was developed by Shizuo Kakutani in 1941,[1] and was used by John Nash in his description of Nash equilibria.[2] It has subsequently found widespread application in game theory and economics.[3]

Statement

Kakutani's theorem states:[4]

- Let S be a non-empty, compact and convex subset of some Euclidean space Rn.

- Let φ: S → 2S be a set-valued function on S with the following properties:

- φ has a closed graph;

- φ(x) is non-empty and convex for all x ∈ S.

- Then φ has a fixed point.

Definitions

- Set-valued function

- A set-valued function φ from the set X to the set Y is some rule that associates one or more points in Y with each point in X. Formally it can be seen just as an ordinary function from X to the power set of Y, written as φ: X → 2Y, such that φ(x) is non-empty for every [math]\displaystyle{ x \in X }[/math]. Some prefer the term correspondence, which is used to refer to a function that for each input may return many outputs. Thus, each element of the domain corresponds to a subset of one or more elements of the range.

- Closed graph

- A set-valued function φ: X → 2Y is said to have a closed graph if the set {(x,y) | y ∈ φ(x)} is a closed subset of X × Y in the product topology i.e. for all sequences [math]\displaystyle{ \{x_n\}_{n\in \mathbb{N}} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \{y_n\}_{n\in \mathbb{N}} }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ x_n\to x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ y_{n}\to y }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y_{n}\in \varphi(x_n) }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math], we have [math]\displaystyle{ y\in \varphi(x) }[/math].

- Fixed point

- Let φ: X → 2X be a set-valued function. Then a ∈ X is a fixed point of φ if a ∈ φ(a).

Examples

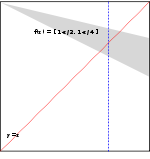

A function with infinitely many fixed points

The function: [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi(x)= [1-x/2, ~1-x/4] }[/math], shown on the figure at the right, satisfies all Kakutani's conditions, and indeed it has many fixed points: any point on the 45° line (dotted line in red) which intersects the graph of the function (shaded in grey) is a fixed point, so in fact there is an infinity of fixed points in this particular case. For example, x = 0.72 (dashed line in blue) is a fixed point since 0.72 ∈ [1 − 0.72/2, 1 − 0.72/4].

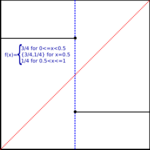

A function with a unique fixed point

The function:

[math]\displaystyle{ \varphi(x)= \begin{cases} 3/4 & 0 \le x \lt 0.5 \\{} [0,1] & x = 0.5 \\ 1/4 & 0.5 \lt x \le 1 \end{cases} }[/math]

satisfies all Kakutani's conditions, and indeed it has a fixed point: x = 0.5 is a fixed point, since x is contained in the interval [0,1].

A function that does not satisfy convexity

The requirement that φ(x) be convex for all x is essential for the theorem to hold.

Consider the following function defined on [0,1]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi(x)= \begin{cases} 3/4 & 0 \le x \lt 0.5 \\ \{ 3/4, 1/4 \} & x = 0.5 \\ 1/4 & 0.5 \lt x \le 1 \end{cases} }[/math]

The function has no fixed point. Though it satisfies all other requirements of Kakutani's theorem, its value fails to be convex at x = 0.5.

A function that does not satisfy closed graph

Consider the following function defined on [0,1]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi(x)= \begin{cases} 3/4 & 0 \le x \lt 0.5 \\ 1/4 & 0.5 \le x \le 1 \end{cases} }[/math]

The function has no fixed point. Though it satisfies all other requirements of Kakutani's theorem, its graph is not closed; for example, consider the sequences xn = 0.5 - 1/n, yn = 3/4.

Alternative statement

Some sources, including Kakutani's original paper, use the concept of upper hemicontinuity while stating the theorem:

- Let S be a non-empty, compact and convex subset of some Euclidean space Rn. Let φ: S→2S be an upper hemicontinuous set-valued function on S with the property that φ(x) is non-empty, closed, and convex for all x ∈ S. Then φ has a fixed point.

This statement of Kakutani's theorem is completely equivalent to the statement given at the beginning of this article.

We can show this by using the closed graph theorem for set-valued functions,[5] which says that for a compact Hausdorff range space Y, a set-valued function φ: X→2Y has a closed graph if and only if it is upper hemicontinuous and φ(x) is a closed set for all x. Since all Euclidean spaces are Hausdorff (being metric spaces) and φ is required to be closed-valued in the alternative statement of the Kakutani theorem, the Closed Graph Theorem implies that the two statements are equivalent.

Applications

Game theory

The Kakutani fixed point theorem can be used to prove the minimax theorem in the theory of zero-sum games. This application was specifically discussed by Kakutani's original paper.[1]

Mathematician John Nash used the Kakutani fixed point theorem to prove a major result in game theory.[2] Stated informally, the theorem implies the existence of a Nash equilibrium in every finite game with mixed strategies for any finite number of players. This work later earned him a Nobel Prize in Economics. In this case:

- The base set S is the set of tuples of mixed strategies chosen by each player in a game. If each player has k possible actions, then each player's strategy is a k-tuple of probabilities summing up to 1, so each player's strategy space is the standard simplex in Rk. Then, S is the cartesian product of all these simplices. It is indeed a nonempty, compact and convex subset of Rkn.

- The function φ(x) associates with each tuple a new tuple where each player's strategy is her best response to other players' strategies in x. Since there may be a number of responses which are equally good, φ is set-valued rather than single-valued. For each x, φ(x) is nonempty since there is always at least one best response. It is convex, since a mixture of two best-responses for a player is still a best-response for the player. It can be proved that φ has a closed graph.

- Then the Nash equilibrium of the game is defined as a fixed point of φ, i.e. a tuple of strategies where each player's strategy is a best response to the strategies of the other players. Kakutani's theorem ensures that this fixed point exists.

General equilibrium

In general equilibrium theory in economics, Kakutani's theorem has been used to prove the existence of set of prices which simultaneously equate supply with demand in all markets of an economy.[6] The existence of such prices had been an open question in economics going back to at least Walras. The first proof of this result was constructed by Lionel McKenzie.[7]

In this case:

- The base set S is the set of tuples of commodity prices.

- The function φ(x) is chosen so that its result differs from its arguments as long as the price-tuple x does not equate supply and demand everywhere. The challenge here is to construct φ so that it has this property while at the same time satisfying the conditions in Kakutani's theorem. If this can be done then φ has a fixed point according to the theorem. Given the way it was constructed, this fixed point must correspond to a price-tuple which equates supply with demand everywhere.

Fair division

Kakutani's fixed-point theorem is used in proving the existence of cake allocations that are both envy-free and Pareto efficient. This result is known as Weller's theorem.

Relation to Brouwer's fixed-point theorem

Brouwer's fixed-point theorem is a special case of Kakutani fixed-point theorem. Conversely, Kakutani fixed-point theorem is an immediate generalization via the approximate selection theorem:[8]

By the approximate selection theorem, there exists a sequence of continuous [math]\displaystyle{ f_n: S \to S }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{graph}(f_n) \subset[\operatorname{graph}(\varphi)]_{1/n} }[/math]. By Brouwer fixed-point theorem, there exists a sequence [math]\displaystyle{ x_n }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ f_n(x_n) = x_n }[/math], so [math]\displaystyle{ (x_n, x_n) \in [\operatorname{graph}(\varphi)]_{1/n} }[/math].

Since [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] is compact, we can take a convergent subsequence [math]\displaystyle{ x_n \to x }[/math]. Then [math]\displaystyle{ (x, x)\in \operatorname{graph}(\varphi) }[/math] since it is a closed set.

Proof outline

S = [0,1]

The proof of Kakutani's theorem is simplest for set-valued functions defined over closed intervals of the real line. However, the proof of this case is instructive since its general strategy can be carried over to the higher-dimensional case as well.

Let φ: [0,1]→2[0,1] be a set-valued function on the closed interval [0,1] which satisfies the conditions of Kakutani's fixed-point theorem.

- Create a sequence of subdivisions of [0,1] with adjacent points moving in opposite directions.

Let (ai, bi, pi, qi) for i = 0, 1, … be a sequence with the following properties:

1. 1 ≥ bi > ai ≥ 0 2. (bi − ai) ≤ 2−i 3. pi ∈ φ(ai) 4. qi ∈ φ(bi) 5. pi ≥ ai 6. qi ≤ bi

Thus, the closed intervals [ai, bi] form a sequence of subintervals of [0,1]. Condition (2) tells us that these subintervals continue to become smaller while condition (3)–(6) tell us that the function φ shifts the left end of each subinterval to its right and shifts the right end of each subinterval to its left.

Such a sequence can be constructed as follows. Let a0 = 0 and b0 = 1. Let p0 be any point in φ(0) and q0 be any point in φ(1). Then, conditions (1)–(4) are immediately fulfilled. Moreover, since p0 ∈ φ(0) ⊂ [0,1], it must be the case that p0 ≥ 0 and hence condition (5) is fulfilled. Similarly condition (6) is fulfilled by q0.

Now suppose we have chosen ak, bk, pk and qk satisfying (1)–(6). Let,

- m = (ak+bk)/2.

Then m ∈ [0,1] because [0,1] is convex.

If there is a r ∈ φ(m) such that r ≥ m, then we take,

- ak+1 = m

- bk+1 = bk

- pk+1 = r

- qk+1 = qk

Otherwise, since φ(m) is non-empty, there must be a s ∈ φ(m) such that s ≤ m. In this case let,

- ak+1 = ak

- bk+1 = m

- pk+1 = pk

- qk+1 = s.

It can be verified that ak+1, bk+1, pk+1 and qk+1 satisfy conditions (1)–(6).

- Find a limiting point of the subdivisions.

The cartesian product [0,1]×[0,1]×[0,1]×[0,1] is a compact set by Tychonoff's theorem. Since the sequence (an, pn, bn, qn) lies in this compact set, it must have a convergent subsequence by the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem. Let's fix attention on such a subsequence and let its limit be (a*, p*,b*,q*). Since the graph of φ is closed it must be the case that p* ∈ φ(a*) and q* ∈ φ(b*). Moreover, by condition (5), p* ≥ a* and by condition (6), q* ≤ b*.

But since (bi − ai) ≤ 2−i by condition (2),

- b* − a* = (lim bn) − (lim an) = lim (bn − an) = 0.

So, b* equals a*. Let x = b* = a*.

Then we have the situation that

- φ(x) ∋ q* ≤ x ≤ p* ∈ φ(x).

- Show that the limiting point is a fixed point.

If p* = q* then p* = x = q*. Since p* ∈ φ(x), x is a fixed point of φ.

Otherwise, we can write the following. Recall that we can parameterize a line between two points a and b by (1-t)a + tb. Using our finding above that q<x<p, we can create such a line between p and q as a function of x (notice the fractions below are on the unit interval). By a convenient writing of x, and since φ(x) is convex and

- [math]\displaystyle{ x=\left(\frac{x-q^*}{p^*-q^*}\right)p^*+\left(1-\frac{x-q^*}{p^*-q^*}\right)q^* }[/math]

it once again follows that x must belong to φ(x) since p* and q* do and hence x is a fixed point of φ.

S is a n-simplex

In dimensions greater one, n-simplices are the simplest objects on which Kakutani's theorem can be proved. Informally, a n-simplex is the higher-dimensional version of a triangle. Proving Kakutani's theorem for set-valued function defined on a simplex is not essentially different from proving it for intervals. The additional complexity in the higher-dimensional case exists in the first step of chopping up the domain into finer subpieces:

- Where we split intervals into two at the middle in the one-dimensional case, barycentric subdivision is used to break up a simplex into smaller sub-simplices.

- While in the one-dimensional case we could use elementary arguments to pick one of the half-intervals in a way that its end-points were moved in opposite directions, in the case of simplices the combinatorial result known as Sperner's lemma is used to guarantee the existence of an appropriate subsimplex.

Once these changes have been made to the first step, the second and third steps of finding a limiting point and proving that it is a fixed point are almost unchanged from the one-dimensional case.

Arbitrary S

Kakutani's theorem for n-simplices can be used to prove the theorem for an arbitrary compact, convex S. Once again we employ the same technique of creating increasingly finer subdivisions. But instead of triangles with straight edges as in the case of n-simplices, we now use triangles with curved edges. In formal terms, we find a simplex which covers S and then move the problem from S to the simplex by using a deformation retract. Then we can apply the already established result for n-simplices.

Infinite-dimensional generalizations

Kakutani's fixed-point theorem was extended to infinite-dimensional locally convex topological vector spaces by Irving Glicksberg[9] and Ky Fan.[10] To state the theorem in this case, we need a few more definitions:

- Upper hemicontinuity

- A set-valued function φ: X→2Y is upper hemicontinuous if for every open set W ⊂ Y, the set {x| φ(x) ⊂ W} is open in X.[11]

- Kakutani map

- Let X and Y be topological vector spaces and φ: X→2Y be a set-valued function. If Y is convex, then φ is termed a Kakutani map if it is upper hemicontinuous and φ(x) is non-empty, compact and convex for all x ∈ X.[11]

Then the Kakutani–Glicksberg–Fan theorem can be stated as:[11]

- Let S be a non-empty, compact and convex subset of a Hausdorff locally convex topological vector space. Let φ: S→2S be a Kakutani map. Then φ has a fixed point.

The corresponding result for single-valued functions is the Tychonoff fixed-point theorem.

There is another version that the statement of the theorem becomes the same as that in the Euclidean case:[5]

- Let S be a non-empty, compact and convex subset of a locally convex Hausdorff space. Let φ: S→2S be a set-valued function on S which has a closed graph and the property that φ(x) is non-empty and convex for all x ∈ S. Then the set of fixed points of φ is non-empty and compact.

Anecdote

In his game theory textbook,[12] Ken Binmore recalls that Kakutani once asked him at a conference why so many economists had attended his talk. When Binmore told him that it was probably because of the Kakutani fixed point theorem, Kakutani was puzzled and replied, "What is the Kakutani fixed point theorem?"

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kakutani, Shizuo (1941). "A generalization of Brouwer's fixed point theorem". Duke Mathematical Journal 8 (3): 457–459. doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-41-00838-4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Nash, J.F. Jr. (1950). "Equilibrium Points in N-Person Games". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 36 (1): 48–49. doi:10.1073/pnas.36.1.48. PMID 16588946. Bibcode: 1950PNAS...36...48N.

- ↑ Border, Kim C. (1989). Fixed Point Theorems with Applications to Economics and Game Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38808-2.

- ↑ Osborne, Martin J.; Rubinstein, Ariel (1994). A Course in Game Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Aliprantis, Charlambos; Kim C. Border (1999). "Chapter 17". Infinite Dimensional Analysis: A Hitchhiker's Guide (3rd ed.). Springer.

- ↑ Starr, Ross M. (1997). General Equilibrium Theory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56473-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Lv3VtS9CcAoC.

- ↑ McKenzie, Lionel (1954). "On Equilibrium in Graham's Model of World Trade and Other Competitive Systems". Econometrica 22 (2): 147–161. doi:10.2307/1907539.

- ↑ Shapiro, Joel H. (2016). A Fixed-Point Farrago. Springer International Publishing. pp. 68–70. ISBN 978-3-319-27978-7. OCLC 984777840.

- ↑ Glicksberg, I.L. (1952). "A Further Generalization of the Kakutani Fixed Point Theorem, with Application to Nash Equilibrium". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 3 (1): 170–174. doi:10.2307/2032478. http://www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=AD0603907.

- ↑ Fan, Ky (1952). "Fixed-point and Minimax Theorems in Locally Convex Topological Linear Spaces". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 38 (2): 121–126. doi:10.1073/pnas.38.2.121. PMID 16589065. Bibcode: 1952PNAS...38..121F.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Dugundji, James; Andrzej Granas (2003). "Chapter II, Section 5.8" (limited preview). Fixed Point Theory. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-00173-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=4_iJAoLSq3cC.

- ↑ Binmore, Ken (2007). "When Do Nash Equilibria Exist?". Playing for Real: A Text on Game Theory (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-19-804114-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=NycDSDcmSM4C&pg=PA256.

Further reading

- Border, Kim C. (1989). Fixed Point Theorems with Applications to Economics and Game Theory. Cambridge University Press. (Standard reference on fixed-point theory for economists. Includes a proof of Kakutani's theorem.)

- Dugundji, James; Andrzej Granas (2003). Fixed Point Theory. Springer. (Comprehensive high-level mathematical treatment of fixed point theory, including the infinite dimensional analogues of Kakutani's theorem.)

- Arrow, Kenneth J.; F. H. Hahn (1971). General Competitive Analysis. Holden-Day. ISBN 978-0-8162-0275-1. https://archive.org/details/generalcompetiti0000arro. (Standard reference on general equilibrium theory. Chapter 5 uses Kakutani's theorem to prove the existence of equilibrium prices. Appendix C includes a proof of Kakutani's theorem and discusses its relationship with other mathematical results used in economics.)

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Kakutani theorem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/k055090

|