Power set

In mathematics, the power set (or powerset) of any set S is the set of all subsets of S, including the empty set and S itself, variously denoted as P(S), 𝒫(S), ℘(S) (using the "Weierstrass p"), P(S), ℙ(S), or, identifying the powerset of S with the set of all functions from S to a given set of two elements, 2S. In axiomatic set theory (as developed, for example, in the ZFC axioms), the existence of the power set of any set is postulated by the axiom of power set.[1]

Any subset of P(S) is called a family of sets over S.

Example

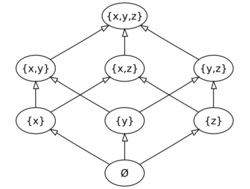

If S is the set {x, y, z}, then the subsets of S are

- {} (also denoted or , the empty set or the null set)

- {x}

- {y}

- {z}

- {x, y}

- {x, z}

- {y, z}

- {x, y, z}

and hence the power set of S is {{}, {x}, {y}, {z}, {x, y}, {x, z}, {y, z}, {x, y, z}}.[2]

Properties

If S is a finite set with |S| = n elements, then the number of subsets of S is |P(S)| = 2n. This fact, which is the motivation for the notation 2S, may be demonstrated simply as follows,

- First, order the elements of S in any manner. We write any subset of S in the format {γ1, γ2, ..., γn } where γi , 1 ≤ i ≤ n, can take the value of 0 or 1. If γi = 1, the i-th element of S is in the subset; otherwise, the i-th element is not in the subset. Clearly the number of distinct subsets that can be constructed this way is 2n as γi ∈ {0, 1} .

Cantor's diagonal argument shows that the power set of a set (whether infinite or not) always has strictly higher cardinality than the set itself (informally the power set must be larger than the original set). In particular, Cantor's theorem shows that the power set of a countably infinite set is uncountably infinite. The power set of the set of natural numbers can be put in a one-to-one correspondence with the set of real numbers (see Cardinality of the continuum).

The power set of a set S, together with the operations of union, intersection and complement can be viewed as the prototypical example of a Boolean algebra. In fact, one can show that any finite Boolean algebra is isomorphic to the Boolean algebra of the power set of a finite set. For infinite Boolean algebras this is no longer true, but every infinite Boolean algebra can be represented as a subalgebra of a power set Boolean algebra (see Stone's representation theorem).

The power set of a set S forms an abelian group when considered with the operation of symmetric difference (with the empty set as the identity element and each set being its own inverse) and a commutative monoid when considered with the operation of intersection. It can hence be shown (by proving the distributive laws) that the power set considered together with both of these operations forms a Boolean ring.

Representing subsets as functions

In set theory, XY is the set of all functions from Y to X. As "2" can be defined as {0,1} (see natural number), 2S (i.e., {0,1}S) is the set of all functions from S to {0,1}. By identifying a function in 2S with the corresponding preimage of 1, we see that there is a bijection between 2S and P(S), where each function is the characteristic function of the subset in P(S) with which it is identified. Hence 2S and P(S) could be considered identical set-theoretically. (Thus there are two distinct notational motivations for denoting the power set by 2S: the fact that this function-representation of subsets makes it a special case of the XY notation and the property, mentioned above, that |2S| = 2|S|.)

This notion can be applied to the example above in which S = {x, y, z} to see the isomorphism with the binary numbers from 0 to 2n − 1 with n being the number of elements in the set. In S, a "1" in the position corresponding to the location in the enumerated set { (x, 0), (y, 1), (z, 2) } indicates the presence of the element. So {x, y} = 011(2).

For the whole power set of S we get:

| Subset | Sequence of digits |

Binary interpretation |

Decimal equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| { } | 0, 0, 0 | 000(2) | 0(10) |

| { x } | 0, 0, 1 | 001(2) | 1(10) |

| { y } | 0, 1, 0 | 010(2) | 2(10) |

| { x, y } | 0, 1, 1 | 011(2) | 3(10) |

| { z } | 1, 0, 0 | 100(2) | 4(10) |

| { x, z } | 1, 0, 1 | 101(2) | 5(10) |

| { y, z } | 1, 1, 0 | 110(2) | 6(10) |

| { x, y, z } | 1, 1, 1 | 111(2) | 7(10) |

Such bijective mapping of S to integers is arbitrary, so this representation of subsets of S is not unique, but the sort order of the enumerated set does not change its cardinality.

However, such finite binary representation is only possible if S can be enumerated (this is possible even if S has an infinite cardinality, such as the set of integers or rationals, but not for example if S is the set of real numbers, in which we cannot enumerate all irrational numbers to assign them a defined finite location in an ordered set containing all irrational numbers).

Relation to binomial theorem

The power set is closely related to the binomial theorem. The number of subsets with k elements in the power set of a set with n elements is given by the number of combinations, C(n, k), also called binomial coefficients.

For example, the power set of a set with three elements, has:

- C(3, 0) = 1 subset with 0 elements (the empty subset),

- C(3, 1) = 3 subsets with 1 element (the singleton subsets),

- C(3, 2) = 3 subsets with 2 elements (the complements of the singleton subsets),

- C(3, 3) = 1 subset with 3 elements (the original set itself).

Using this relationship we can compute using the formula:

Therefore, one can deduce the following identity, assuming :

Recursive definition

If is a finite set, there is a recursive definition of .

- If , then .

- Otherwise, let and ; then .

In words:

- The power set of the empty set is a singleton whose only element is the empty set.

- For a non-empty set , let be any element of the set and its relative complement; then the power set of is a union of a power set of and a power set of whose each element is expanded with the element.

Subsets of limited cardinality

The set of subsets of S of cardinality less than or equal to κ is sometimes denoted by Pκ(S) or [S]κ, and the set of subsets with cardinality strictly less than κ is sometimes denoted P< κ(S) or [S]<κ. Similarly, the set of non-empty subsets of S might be denoted by P≥ 1(S) or P+(S).

Power object

A set can be regarded as an algebra having no nontrivial operations or defining equations. From this perspective the idea of the power set of X as the set of subsets of X generalizes naturally to the subalgebras of an algebraic structure or algebra.

Now the power set of a set, when ordered by inclusion, is always a complete atomic Boolean algebra, and every complete atomic Boolean algebra arises as the lattice of all subsets of some set. The generalization to arbitrary algebras is that the set of subalgebras of an algebra, again ordered by inclusion, is always an algebraic lattice, and every algebraic lattice arises as the lattice of subalgebras of some algebra. So in that regard subalgebras behave analogously to subsets.

However, there are two important properties of subsets that do not carry over to subalgebras in general. First, although the subsets of a set form a set (as well as a lattice), in some classes it may not be possible to organize the subalgebras of an algebra as itself an algebra in that class, although they can always be organized as a lattice. Secondly, whereas the subsets of a set are in bijection with the functions from that set to the set {0,1} = 2, there is no guarantee that a class of algebras contains an algebra that can play the role of 2 in this way.

Certain classes of algebras enjoy both of these properties. The first property is more common, the case of having both is relatively rare. One class that does have both is that of multigraphs. Given two multigraphs G and H, a homomorphism h: G → H consists of two functions, one mapping vertices to vertices and the other mapping edges to edges. The set HG of homomorphisms from G to H can then be organized as the graph whose vertices and edges are respectively the vertex and edge functions appearing in that set. Furthermore, the subgraphs of a multigraph G are in bijection with the graph homomorphisms from G to the multigraph Ω definable as the complete directed graph on two vertices (hence four edges, namely two self-loops and two more edges forming a cycle) augmented with a fifth edge, namely a second self-loop at one of the vertices. We can therefore organize the subgraphs of G as the multigraph ΩG, called the power object of G.

What is special about a multigraph as an algebra is that its operations are unary. A multigraph has two sorts of elements forming a set V of vertices and E of edges, and has two unary operations s,t: E → V giving the source (start) and target (end) vertices of each edge. An algebra all of whose operations are unary is called a presheaf. Every class of presheaves contains a presheaf Ω that plays the role for subalgebras that 2 plays for subsets. Such a class is a special case of the more general notion of elementary topos as a category that is closed (and moreover cartesian closed) and has an object Ω, called a subobject classifier. Although the term "power object" is sometimes used synonymously with exponential object YX, in topos theory Y is required to be Ω.

Functors and quantifiers

In category theory and the theory of elementary topoi, the universal quantifier can be understood as the right adjoint of a functor between power sets, the inverse image functor of a function between sets; likewise, the existential quantifier is the left adjoint.[3]

See also

- Set theory

- Axiomatic set theory

- Family of sets

- Field of sets

Notes

- ↑ Devlin 1979, p. 50

- ↑ Puntambekar 2007, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Saunders Mac Lane, Ieke Moerdijk, (1992) Sheaves in Geometry and Logic Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-97710-4 See page 58

References

- Devlin, Keith J. (1979). Fundamentals of contemporary set theory. Universitext. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90441-7.

- Halmos, Paul R. (1960). Naive set theory. The University Series in Undergraduate Mathematics. van Nostrand Company. https://archive.org/details/naivesettheory00halm.

- Puntambekar, A. A. (2007). Theory Of Automata And Formal Languages. Technical Publications. ISBN 978-81-8431-193-8.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Power Set". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/PowerSet.html.

- Power set at PlanetMath.org.

- Power set in nLab

- Power object in nLab

- Power set Algorithm in C++