Biology:APOBEC3G

Generic protein structure example |

APOBEC3G (apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic subunit 3G) is a human enzyme encoded by the APOBEC3G gene that belongs to the APOBEC superfamily of proteins.[1] This family of proteins has been suggested to play an important role in innate anti-viral immunity.[2] APOBEC3G belongs to the family of cytidine deaminases that catalyze the deamination of cytidine to uridine in the single stranded DNA substrate.[1] The C-terminal domain of A3G renders catalytic activity, several NMR and crystal structures explain the substrate specificity and catalytic activity.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

APOBEC3G exerts innate antiretroviral immune activity against retroviruses, most notably HIV, by interfering with proper replication. However, lentiviruses such as HIV have evolved the Viral infectivity factor (Vif) protein in order to counteract this effect. Vif interacts with APOBEC3G and triggers the ubiquitination and degradation of APOBEC3G via the proteasomal pathway.[11] On the other hand, foamy viruses produce an accessory protein Bet (P89873) that impairs the cytoplasmic solubility of APOBEC3G.[12] The two ways of inhibition are distinct from each other, but they can replace each other in vivo.[13]

Discovery

It was first identified by Jarmuz et al.[14] as a member of family of proteins APOBEC3A to 3G on chromosome 22 in 2002 and later also as a cellular factor able to restrict replication of HIV-1 lacking the viral accessory protein Vif. Soon after, it was shown that APOBEC3G belonged to a family of proteins grouped together due to their homology with the cytidine deaminase APOBEC1.

Structure

APOBEC3G has a symmetric structure, resulting in 2 homologous catalytic domains, the N-terminal (CD1) and C-terminal (CD2) domains, each of which contains a Zn2+ coordination site.[15] Each domain also has the typical His/Cys-X-Glu-X23–28-Pro-Cys-X2-Cys motif for cytidine deaminases. However, unlike the typical cytidine deaminases, APOBEC3G contains a unique alpha helix between two beta sheets in the catalytic domain that could be a cofactor binding site.[16] (Figure 1)

CD2 is catalytically active and vital for deamination and motif specificity. CD1 is catalytically inactive, but very important for binding to DNA and RNA and is key to defining the 5’->3’ processivity of APOBEC3G deamination.[17] CD2 has no deaminase activity without the presence of CD1.[18]

Native APOBEC3G is composed of monomers, dimers, trimers, tetramers, and higher order oligomers. While it is thought that APOBEC3G functions as a dimer, it is possible that it actually functions as a mix of monomers and oligomers.[17]

The D128 amino acid residue, which lies within CD1 (Figure 1), appears to be particularly important for APOBEC3G interactions with Vif because a D128K point mutation prevents Vif-dependent depletion of APOBEC3G.[19][20] Additionally, amino acids 128–130 on APOBEC3G form a negatively charged motif that is critical for interactions with Vif and the formation of APOBEC3G-Vif complexes. Furthermore, residues 124-127 are important for encapsidation of APOBEC3G into HIV-1 virions and the resulting antiretroviral activity.[21]

Mechanism of action

APOBEC3G has been widely studied and several mechanisms that negatively affect HIV-1 replication have been identified.

Cytidine deamination and hypermutation

APOBEC3G and other proteins in the same family are able to act as activation-induced (cytidine) deaminases (AID). APOBEC3G interferes with reverse transcription by inducing numerous deoxycytidine to deoxyuridine mutations in the negative strand of the HIV DNA primarily expressed as complementary DNA (cDNA)[11] in a 3’->5’processive manner.[22] Because APOBEC3G is part of the APOBEC superfamily and acts as an AID, it is likely that the mechanism mediated by APOBEC3G for cytidine deamination is similar to that of an E. coli cytidine deaminase that is known to be highly homologous to APOBEC1 and AID around the nucleotide and zinc-binding region. The predicted deamination reaction is driven by a direct nucleophilic attack on position 4 of the cytidine pyrimidine ring by the zinc-coordinated enzyme. Water is needed as a source of both a proton and hydroxyl group donor (Figure 2).[23] The deamination (and resulting oxidation) at position 4 yields a carbonyl group and results in a change from cytidine to uridine.

The deamination activity ultimately results in G→A hypermutations at “hot spots” of the proviral DNA. Such hypermutation ultimately destroys the coding and replicative capacity of the virus, resulting in many nonviable virions.[11][24] APOBEC3G has a much weaker antiviral effect when its active site has been mutated to the point that the protein can no longer mutate retroviral DNA.[25] It was originally thought that the APOBEC3G-mediated deamination can also indirectly lead to viral DNA degradation by DNA repair systems attracted to the mutated residues.[26] However, this has been discounted because human APOBEC3G reduces viral cDNA levels independently of DNA repair enzymes UNG and SMUG1.[27]

Interference with reverse transcription

APOBEC3G interferes with reverse transcription of HIV-1 independent of DNA deamination. tRNA3Lys typically binds to the HIV-1 primer binding site to initiate reverse transcription. APOBEC3G can inhibit tRNA3Lys priming, thereby negatively affecting viral ssDNA production and virus infectivity.[26] It is predicted that reverse transcription is also negatively affected by APOBEC3G binding to viral RNA and causing steric alterations.[15]

Interference with viral DNA integration

APOBEC3G was associated with interference of viral DNA integration into the host genome in a manner dependent on functional catalytic domains and deaminase activity. Mbisa et al. saw that APOBEC3G interferes with the processing and removal of primer tRNA from the DNA minus strand, thus leading to aberrant viral 3’ long terminal repeat (LTR) DNA ends. These viral DNA ends are inefficient substrates for integration and plus-strand DNA transfer. As a result, HIV-1 provirus formation is inhibited.[22]

Biological function

HIV encapsidation

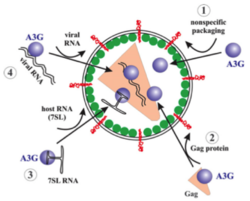

APOBEC3G mRNA is expressed in certain cells, referred to as non-permissive cells, in which HIV-1 cannot properly infect and replicate in the absence of Vif. Such cells include physiologically relevant primary CD4 T lymphocytes and macrophages.[29] The encapsidation of APOBEC3G into HIV-1 virions is very important for the spread of APOBEC3G and the exertion of anti-retroviral activity. Encapsidation of APOBEC3G may occur by at least the following four proposed mechanisms (Figure 3): 1. Non-specific packaging of APOBEC3G 2. APOBEC3G interaction with host RNA 3. APOBEC3G interaction with viral RNA 4. Interaction of APOBEC3G with HIV-1 Gag proteins. Only the latter two mechanisms have been extensively supported.[28]

The amount that is incorporated into virions is dependent on the level of APOBEC3G expression within the cell producing the virion. Xu et al. conducted studies with PBMC cells and found that, in the absence of Vif, 7±4 APOBEC3G molecules were incorporated into the virions and resulted in potent inhibition of HIV-1 replication.[30]

In addition to deterring replication of exogenous retroviruses, A3G also acts upon human endogenous retroviruses, leaving similar signatures of hypermutations in them.[31][32]

Disease relevance

APOBEC3G is expressed within the non-permissive cells and is a key inhibitory factor of HIV-1 replication and infectivity. However, Vif counteracts this antiretroviral factor, enabling production of viable and infective HIV-1 virions in the presence of APOBEC3G activity .[29][33] In particular, Vif prevents incorporation of APOBEC3G into HIV-1 virions and promotes destruction of the enzyme in a manner independent of all other HIV-1 proteins.[34]

While APOBEC3G has typically been studied as a vital protein exhibiting potent antiviral effects on HIV-1, recent studies have elucidated the potential of APOBEC3G-mediated mutation to help to facilitate the propagation HIV-1. The number of deaminations in the preferred regions varies from one to many, possibly dependent on the time of exposure to APOBEC3G.[24] Additionally, it has been shown that there is a dose response between intracellular APOBEC3G concentration and degree of viral hypermutation.[35] Some HIV-1 proviruses with APOBEC3G-mediated mutation have been shown to thrive because they carry too few mutations at APOBEC3G hotspots or because recombination between a lethally APOBEC3G-restricted provirus and a viable provirus has occurred.[36] Such sublethal mutagenesis contributes to greater genetic diversity among the HIV-1 virus population, demonstrating the potential for APOBEC3G to enhance HIV-1's ability to adapt and propagate.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein". Nature 418 (6898): 646–50. August 2002. doi:10.1038/nature00939. PMID 12167863. Bibcode: 2002Natur.418..646S.

- ↑ "[Antiviral defense by APOBEC3 family proteins]" (in ja). Uirusu 55 (2): 267–72. December 2005. doi:10.2222/jsv.55.267. PMID 16557012.

- ↑ "Structural features of antiviral DNA cytidine deaminases". Biological Chemistry 394 (11): 1357–70. November 2013. doi:10.1515/hsz-2013-0165. PMID 23787464. http://juser.fz-juelich.de/record/139785/files/FZJ-2013-05757.pdf.

- ↑ "Structure of the DNA deaminase domain of the HIV-1 restriction factor APOBEC3G". Nature 452 (7183): 116–9. March 2008. doi:10.1038/nature06638. PMID 18288108. Bibcode: 2008Natur.452..116C.

- ↑ "Crystal structure of the APOBEC3G catalytic domain reveals potential oligomerization interfaces". Structure 18 (1): 28–38. January 2010. doi:10.1016/j.str.2009.10.016. PMID 20152150.

- ↑ "Crystal structure of the anti-viral APOBEC3G catalytic domain and functional implications". Nature 456 (7218): 121–4. November 2008. doi:10.1038/nature07357. PMID 18849968. Bibcode: 2008Natur.456..121H.

- ↑ "Structure, interaction and real-time monitoring of the enzymatic reaction of wild-type APOBEC3G". The EMBO Journal 28 (4): 440–51. February 2009. doi:10.1038/emboj.2008.290. PMID 19153609.

- ↑ "An extended structure of the APOBEC3G catalytic domain suggests a unique holoenzyme model". Journal of Molecular Biology 389 (5): 819–32. June 2009. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.031. PMID 19389408.

- ↑ "First-in-class small molecule inhibitors of the single-strand DNA cytosine deaminase APOBEC3G". ACS Chemical Biology 7 (3): 506–17. March 2012. doi:10.1021/cb200440y. PMID 22181350.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "The HIV-1 Vif PPLP motif is necessary for human APOBEC3G binding and degradation". Virology 377 (1): 49–53. July 2008. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.017. PMID 18499212.

- ↑ "Prototype foamy virus Bet impairs the dimerization and cytosolic solubility of human APOBEC3G". Journal of Virology 87 (16): 9030–40. August 2013. doi:10.1128/JVI.03385-12. PMID 23760237.

- ↑ "Replacement of feline foamy virus bet by feline immunodeficiency virus vif yields replicative virus with novel vaccine candidate potential". Retrovirology 15 (1): 38. May 2018. doi:10.1186/s12977-018-0419-0. PMID 29769087.

- ↑ "An anthropoid-specific locus of orphan C to U RNA-editing enzymes on chromosome 22". Genomics 79 (3): 285–96. March 2002. doi:10.1006/geno.2002.6718. PMID 11863358.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Novel targets for HIV therapy". Antiviral Research 80 (3): 251–65. December 2008. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.08.003. PMID 18789977. https://zenodo.org/record/3414333.

- ↑ "Cytidine deamination and resistance to retroviral infection: towards a structural understanding of the APOBEC proteins". Virology 334 (2): 147–53. April 2005. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.038. PMID 15780864.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Structural model for deoxycytidine deamination mechanisms of the HIV-1 inactivation enzyme APOBEC3G". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 (21): 16195–205. May 2010. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.107987. PMID 20212048.

- ↑ "Functional analysis of the two cytidine deaminase domains in APOBEC3G". Virology 414 (2): 130–6. June 2011. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2011.03.014. PMID 21489586.

- ↑ "Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif". Cell 114 (1): 21–31. July 2003. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00515-4. PMID 12859895.

- ↑ "A single amino acid substitution in human APOBEC3G antiretroviral enzyme confers resistance to HIV-1 virion infectivity factor-induced depletion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (15): 5652–7. April 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0400830101. PMID 15054139. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..101.5652X.

- ↑ "Identification of amino acid residues in APOBEC3G required for regulation by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif and Virion encapsidation". Journal of Virology 81 (8): 3807–15. April 2007. doi:10.1128/JVI.02795-06. PMID 17267497.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cDNAs produced in the presence of APOBEC3G exhibit defects in plus-strand DNA transfer and integration". Journal of Virology 81 (13): 7099–110. July 2007. doi:10.1128/JVI.00272-07. PMID 17428871.

- ↑ "Immunity through DNA deamination". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 28 (6): 305–12. June 2003. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00111-7. PMID 12826402.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "APOBEC3G contributes to HIV-1 variation through sublethal mutagenesis". Journal of Virology 84 (14): 7396–404. July 2010. doi:10.1128/JVI.00056-10. PMID 20463080.

- ↑ "HIV-1 Vif, APOBEC, and intrinsic immunity". Retrovirology 5 (1): 51. June 2008. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-5-51. PMID 18577210.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Inhibition of tRNA₃(Lys)-primed reverse transcription by human APOBEC3G during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication". Journal of Virology 80 (23): 11710–22. December 2006. doi:10.1128/JVI.01038-06. PMID 16971427.

- ↑ "Human APOBEC3G can restrict retroviral infection in avian cells and acts independently of both UNG and SMUG1". Journal of Virology 82 (9): 4660–4. May 2008. doi:10.1128/JVI.02469-07. PMID 18272574.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "APOBEC3G encapsidation into HIV-1 virions: which RNA is it?". Retrovirology 5 (55): 55. July 2008. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-5-55. PMID 18597677.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "HIV-1 Vif versus the APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases: an intracellular duel between pathogen and host restriction factors". Molecular Aspects of Medicine 31 (5): 383–97. October 2010. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2010.06.001. PMID 20538015.

- ↑ "Stoichiometry of the antiviral protein APOBEC3G in HIV-1 virions". Virology 360 (2): 247–56. April 2007. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.036. PMID 17126871.

- ↑ "Conserved footprints of APOBEC3G on Hypermutated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K(HML2) sequences". Journal of Virology 82 (17): 8743–61. September 2008. doi:10.1128/JVI.00584-08. PMID 18562517.

- ↑ "Hypermutation of an ancient human retrovirus by APOBEC3G". Journal of Virology 82 (17): 8762–70. September 2008. doi:10.1128/JVI.00751-08. PMID 18562521.

- ↑ "HIV-1 Vif and APOBEC3G: multiple roads to one goal". Retrovirology 1 (28): 28. September 2004. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-1-28. PMID 15383144.

- ↑ "HIV-1 Vif blocks the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by impairing both its translation and intracellular stability". Molecular Cell 12 (3): 591–601. September 2003. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00353-8. PMID 14527406.

- ↑ "Turning up the volume on mutational pressure: is more of a good thing always better? (A case study of HIV-1 Vif and APOBEC3)". Retrovirology 5 (26): 26. March 2008. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-5-26. PMID 18339206.

- ↑ "Cytidine deamination induced HIV-1 drug resistance". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (14): 5501–6. April 2008. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710190105. PMID 18391217. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..105.5501M.

External links

- Human APOBEC3G genome location and APOBEC3G gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

Further reading

- "The APOBEC-2 crystal structure and functional implications for the deaminase AID". Nature 445 (7126): 447–51. January 2007. doi:10.1038/nature05492. PMID 17187054. Bibcode: 2007Natur.445..447P.

- "Differential anti-APOBEC3G activity of HIV-1 Vif proteins derived from different subtypes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 (46): 35350–8. November 2010. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.173286. PMID 20833716.

|