Biology:Arginase

| Liver arginase | |

|---|---|

| |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | ARG1 |

| NCBI gene | 383 |

| HGNC | 663 |

| OMIM | 608313 |

| RefSeq | NM_000045 |

| UniProt | P05089 |

| Other data | |

| EC number | 3.5.3.1 |

| Locus | Chr. 6 q23 |

| Arginase, type II | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | ARG2 |

| NCBI gene | 384 |

| HGNC | 664 |

| OMIM | 107830 |

| RefSeq | NM_001172 |

| UniProt | P78540 |

| Other data | |

| EC number | 3.5.3.1 |

| Locus | Chr. 14 q24.1 |

Arginase (EC 3.5.3.1, arginine amidinase, canavanase, L-arginase, arginine transamidinase) is a manganese-containing enzyme. The reaction catalyzed by this enzyme is:

It is the final enzyme of the urea cycle. It is ubiquitous to all domains of life.

Structure and function

Arginase belongs to the ureohydrolase family of enzymes.

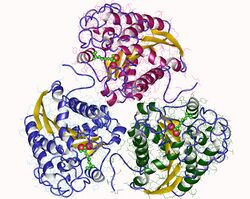

Arginase catalyzes the fifth and final cytosolic step in the urea cycle, a series of biochemical reactions in mammals during which the body disposes of harmful ammonia. Specifically, arginase converts L-arginine into L-ornithine and urea.[1] Mammalian arginase is active as a trimer, but some bacterial arginases are hexameric.[2] The enzyme requires a binuclear manganese cluster for optimal activity. A single hydroxide ion bridges these Mn2+ ions, oriented to serve as a nucleophile that attacks the guanidinium group of L-arginine, hydrolyzing it to form ornithine and urea.[3]

In most mammals, two isozymes of this enzyme exist; the first, Arginase I, functions in the urea cycle, and is located primarily in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (liver cells). The second isozyme, Arginase II, has been implicated in the regulation of intracellular arginine/ornithine levels. It is located in mitochondria of several tissues in the body, with most abundance in the kidney and prostate. It may be found at lower levels in macrophages, lactating mammary glands, and brain.[4] The second isozyme may be found in the absence of other urea cycle enzymes.[3]

Structure and Mechanism

The first crystal structure of arginase was reported in 1996 by the research group of David W. Christianson at the University of Pennsylvania.[5] The mechanism advanced in this paper begins with the binding of L-arginine in the enzyme active site, held in place by hydrogen bonding between the guanidinium group and Glu227. This orients the guanidinium group for nucleophilic attack by the metal-bridging hydroxide ion to form a tetrahedral intermediate. The manganese ions stabilize the hydroxyl group in the tetrahedral intermediate, as well as the developing sp3 lone electron pair on the NH2 group as the tetrahedral intermediate is formed.[6]

Arginase exhibits very narrow specificity for substrate L-arginine.[7] Modifying the substrate structure and/or stereochemistry severely diminishes catalytic activity. This specificity results from the high number of hydrogen bonds between substrate and enzyme; direct or water-mediated hydrogen bonds saturate both the four acceptor positions on the alpha carboxylate group and all three donor positions on the alpha amino group.[8] N-hydroxy-L-arginine (NOHA), an intermediate of NO biosynthesis, is a moderate inhibitor of arginase. The crystal structure of its complex with the enzyme reveals that it displaces the metal-bridging hydroxide ion and bridges the binuclear manganese cluster.[7]

2(S)-Amino-6-boronohexonic acid (ABH)[9] is an L-arginine analogue that binds as a tetrahedral boronate anion, which mimics the tetrahedral intermediate formed in catalysis; ABH is a potent inhibitor of human arginase I.[8][10]

Role in sexual response

Arginase II is coexpressed with nitric oxide (NO) synthase in smooth muscle tissue, such as the muscle in the genitals of both men and women. The contraction and relaxation of these muscles is regulated by nitric oxide (NO) generated by NO synthase, which causes rapid relaxation of smooth muscle tissue and facilitates engorgement of tissue necessary for normal sexual response. However, since NO synthase and arginase compete for the same substrate (L-arginine), over-expressed arginase can affect NO synthase activity and NO-dependent smooth muscle relaxation by depleting the substrate pool of L-arginine that would otherwise be available to NO synthase. In contrast, inhibiting arginase with ABH or other boronic acid inhibitors will maintain normal cellular levels of arginine, thus allowing for normal muscle relaxation and sexual response.[11]

Arginase is a controlling factor in both male erectile function and female sexual arousal, and is therefore a potential target for treatment of sexual dysfunction in both sexes.[12] Additionally, supplementing the diet with additional L-arginine will decrease the amount of competition between arginase and NO synthase by providing extra substrate for each enzyme.[13] Arginase also regulates NO-dependent processes in the immune response.[14]

Pathology

Arginase deficiency typically refers to decreased function of arginase I, the liver isoform of arginase. This deficiency is commonly referred to as hyperargininemia or arginemia. The disorder is hereditary and autosomal recessive. It is characterized by lowered activity of arginase in hepatic cells. It is considered to be the rarest of the heritable defects in ureagenesis. Arginase deficiency, unlike other urea cycle disorders, does not entirely prevent ureagenesis. A proposed reason for the continuation of arginase function is suggested by increased activity of arginase II in the kidneys of subjects with arginase I deficiency. Researchers believe that buildup of arginine triggers increased expression of arginase II. The enzymes in the kidney will then catalyze ureagenesis, compensating somewhat for a decrease in arginase I activity in the liver. Due to this alternate method of removing excess arginine and ammonia from the bloodstream, subjects with arginase deficiency tend to have longer lifespans than those who have other urea cycle defects.[15]

Symptoms of the disorder include neurological impairment, dementia, retardation of growth, and hyperammonemia. While some symptoms of the disease can be controlled via dietary restrictions and pharmaceutical developments, no cure or completely effective therapy currently exists.[15]

References

- ↑ "Arginine metabolism: nitric oxide and beyond". The Biochemical Journal. 336 ( Pt 1) (Pt 1): 1–17. November 1998. doi:10.1042/bj3360001. PMID 9806879. PMC 1219836. http://www.biochemj.org/bj/336/0001/bj3360001.htm.

- ↑ "Evolution of the arginase fold and functional diversity". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65 (13): 2039–55. July 2008. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-7554-z. PMID 18360740.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Expression, purification, assay, and crystal structure of perdeuterated human arginase I". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 465 (1): 82–9. September 2007. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2007.04.036. PMID 17562323.

- ↑ Morris SM (2002). "Regulation of enzymes of the urea cycle and arginine metabolism". Annual Review of Nutrition 22 (1): 87–105. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.110801.140547. PMID 12055339.

- ↑ "Structure of a unique binuclear manganese cluster in arginase". Nature 383 (6600): 554–557. 1996. doi:10.1038/383554a0. PMID 8849731. Bibcode: 1996Natur.383..554K. https://www.nature.com/articles/383554a0.

- ↑ "Arginase: Structure, Mechanism, and Physiological Role in Male and Female Sexual Arousal". Accounts of Chemical Research 38 (3): 191–201. 2005. doi:10.1021/ar040183k. PMID 15766238. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ar040183k.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Rat liver arginase: kinetic mechanism, alternate substrates, and inhibitors". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 312 (1): 31–7. July 1994. doi:10.1006/abbi.1994.1276. PMID 8031143.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Arginase-boronic acid complex highlights a physiological role in erectile function". Nature Structural Biology 6 (11): 1043–7. November 1999. doi:10.1038/14929. PMID 10542097.

- ↑ "Inhibition of Mn2+2-Arginase by Borate Leads to the Design of a Transition State Analogue Inhibitor, 2( S )-Amino-6-boronohexanoic Acid". Journal of the American Chemical Society 119 (34): 8107–8108. 1997. doi:10.1021/ja971312d. Bibcode: 1997JAChS.119.8107B. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ja971312d.

- ↑ "Crystal structure of human arginase I at 1.29-Å resolution and exploration of inhibition in the immune response". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102 (37): 13058–13063. 2005. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504027102. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..10213058D.

- ↑ "Human arginase II: crystal structure and physiological role in male and female sexual arousal". Biochemistry 42 (28): 8445–51. July 2003. doi:10.1021/bi034340j. PMID 12859189.

- ↑ "Arginase: Structure, Mechanism, and Physiological Role in Male and Female Sexual Arousal". Accounts of Chemical Research 38 (3): 191–201. 2005. doi:10.1021/ar040183k. PMID 15766238. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ar040183k.

- ↑ "Effects of long-term oral administration of L-arginine on the rat erectile response". The Journal of Urology 158 (3 Pt 1): 942–7. September 1997. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64368-4. PMID 9258123.

- ↑ "Crystal structure of human arginase I at 1.29-Å resolution and exploration of inhibition in the immune response". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102 (37): 13058–13063. 2005. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504027102. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..10213058D.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Mouse model for human arginase deficiency". Molecular and Cellular Biology 22 (13): 4491–8. July 2002. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.13.4491-4498.2002. PMID 12052859.

External links

- Arginase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- GeneReviews/NIH/NCBI/UW entry on Arginase Deficiency

- Arginase family signature and profile in PROSITE

|