Medicine:Coronary artery disease

| Coronary artery disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Atherosclerotic heart disease,[1] atherosclerotic vascular disease,[2] coronary heart disease[3] |

| |

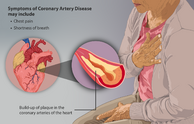

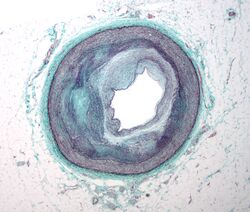

| Illustration depicting atherosclerosis in a coronary artery | |

| Specialty | Cardiology, cardiac surgery |

| Symptoms | Chest pain, shortness of breath[4] |

| Complications | Heart failure, abnormal heart rhythms, heart attack, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest[5] |

| Causes | Atherosclerosis of the arteries of the heart[6] |

| Risk factors | High blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, lack of exercise, obesity, high blood cholesterol[6][7] |

| Diagnostic method | Electrocardiogram, cardiac stress test, coronary computed tomographic angiography, coronary angiogram[8] |

| Prevention | Healthy diet, regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, not smoking[9] |

| Treatment | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG)[10] |

| Medication | Aspirin, beta blockers, nitroglycerin, statins[10] |

| Frequency | 110 million (2015)[11] |

| Deaths | 8.9 million (2015)[12] |

Coronary artery disease (CAD), also called coronary heart disease (CHD), ischemic heart disease (IHD),[13] myocardial ischemia,[14] or simply heart disease, involves the reduction of blood flow to the heart muscle due to build-up of atherosclerotic plaque in the arteries of the heart.[5][6][15] It is the most common of the cardiovascular diseases.[16] Types include stable angina, unstable angina, and myocardial infarction.[17]

A common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may travel into the shoulder, arm, back, neck, or jaw.[4] Occasionally it may feel like heartburn. Usually symptoms occur with exercise or emotional stress, last less than a few minutes, and improve with rest.[4] Shortness of breath may also occur and sometimes no symptoms are present.[4] In many cases, the first sign is a heart attack.[5] Other complications include heart failure or an abnormal heartbeat.[5]

Risk factors include high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, lack of exercise, obesity, high blood cholesterol, poor diet, depression, and excessive alcohol consumption.[6][7][18] A number of tests may help with diagnoses including: electrocardiogram, cardiac stress testing, coronary computed tomographic angiography, and coronary angiogram, among others.[8]

Ways to reduce CAD risk include eating a healthy diet, regularly exercising, maintaining a healthy weight, and not smoking.[19][9] Medications for diabetes, high cholesterol, or high blood pressure are sometimes used.[9] There is limited evidence for screening people who are at low risk and do not have symptoms.[20] Treatment involves the same measures as prevention.[10][21] Additional medications such as antiplatelets (including aspirin), beta blockers, or nitroglycerin may be recommended.[10] Procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) may be used in severe disease.[10][22] In those with stable CAD it is unclear if PCI or CABG in addition to the other treatments improves life expectancy or decreases heart attack risk.[23]

In 2015, CAD affected 110 million people and resulted in 8.9 million deaths.[11][12] It makes up 15.6% of all deaths, making it the most common cause of death globally.[12] The risk of death from CAD for a given age decreased between 1980 and 2010, especially in developed countries.[24] The number of cases of CAD for a given age also decreased between 1990 and 2010.[25] In the United States in 2010, about 20% of those over 65 had CAD, while it was present in 7% of those 45 to 64, and 1.3% of those 18 to 45;[26] rates were higher among males than females of a given age.[26]

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort that occurs regularly with activity, after eating, or at other predictable times; this phenomenon is termed stable angina and is associated with narrowing of the arteries of the heart. Angina also includes chest tightness, heaviness, pressure, numbness, fullness, or squeezing.[27] Angina that changes in intensity, character or frequency is termed unstable. Unstable angina may precede myocardial infarction. In adults who go to the emergency department with an unclear cause of pain, about 30% have pain due to coronary artery disease.[28] Angina, shortness of breath, sweating, nausea or vomiting, and lightheadedness are signs of a heart attack, or myocardial infarction, and immediate emergency medical services are crucial.[27]

With advanced disease, the narrowing of coronary arteries reduces the supply of oxygen-rich blood flowing to the heart, which becomes more pronounced during strenuous activities during which the heart beats faster.[29] For some, this causes severe symptoms, while others experience no symptoms at all.[4]

Symptoms in females

Symptoms in females can differ from those in males, and the most common symptom reported by females of all races is shortness of breath.[30] Other symptoms more commonly reported by females than males are extreme fatigue, sleep disturbances, indigestion, and anxiety.[31] However, some females do experience irregular heartbeat, dizziness, sweating, and nausea.[27] Burning, pain, or pressure in the chest or upper abdomen that can travel to the arm or jaw can also be experienced in females, but it is less commonly reported by females than males.[31] On average, females experience symptoms 10 years later than males.[32] females are less likely to recognize symptoms and seek treatment.[27]

Risk factors

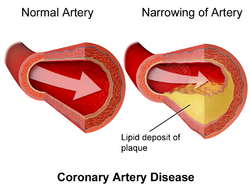

Coronary artery disease is characterized by heart problems that result from atherosclerosis.[33] Atherosclerosis is a type of arteriosclerosis which is the "chronic inflammation of the arteries which causes them to harden and accumulate cholesterol plaques (atheromatous plaques) on the artery walls".[34] CAD has a number of well determined risk factors that contribute to atherosclerosis. These risk factors for CAD include "smoking, diabetes, high blood pressure (hypertension), abnormal (high) amounts of cholesterol and other fat in the blood (dyslipidemia), type 2 diabetes and being overweight or obese (having excess body fat)" due to lack of exercise and a poor diet.[35] Some other risk factors include high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, lack of exercise, obesity, high blood cholesterol, poor diet, depression, family history, psychological stress and excessive alcohol.[6][7][18] About half of cases are linked to genetics.[36] Smoking and obesity are associated with about 36% and 20% of cases, respectively.[37] Smoking just one cigarette per day about doubles the risk of CAD.[38] Lack of exercise has been linked to 7–12% of cases.[37][39] Exposure to the herbicide Agent Orange may increase risk.[40] Rheumatologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis are independent risk factors as well.[41][42][43][44][excessive citations]

Job stress appears to play a minor role accounting for about 3% of cases.[37] In one study, females who were free of stress from work life saw an increase in the diameter of their blood vessels, leading to decreased progression of atherosclerosis.[45] In contrast, females who had high levels of work-related stress experienced a decrease in the diameter of their blood vessels and significantly increased disease progression.[45] Having a type A behavior pattern, a group of personality characteristics including time urgency, competitiveness, hostility, and impatience,[46] is linked to an increased risk of coronary disease.[47]

Blood fats

The consumption of different types of fats including trans unsaturated, saturated and trans in a diet "influences the level of cholesterol that is present in the bloodstream".[48] Unsaturated fats originate from plant sources (such as oils). There are two types of unsaturated fats, cis and trans isomers. Cis unsaturated fats are bent in molecular structure and trans are linear in structure. Saturated fats originate from animal sources (such as animal fats) and are also molecularly linear in structure.[49] The linear configurations of unsaturated trans and saturated fats allow them to easily accumulate and stack at the arterial walls when consumed in high amounts (and other positive measures towards physical health are not met).

- Fats and cholesterol are insoluble in blood and thus are amalgamated with proteins to form lipoproteins for transport. Low density lipoproteins (LDL) transport cholesterol from the liver to the rest of the body and therefore raise blood cholesterol levels. The consumption of "saturated fats increases LDL levels within the body, thus raising blood cholesterol levels".[48]

- High density lipoproteins (HDL) are considered 'good' lipoproteins as they search for excess cholesterol in the body and transport it back to the liver for disposal. Trans fats also "increase LDL levels whilst decreasing HDL levels within the body, significantly raising blood cholesterol levels".[48]

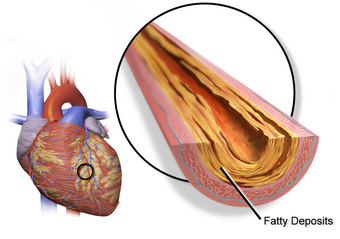

High levels of cholesterol in the bloodstream lead to atherosclerosis. With increased levels of LDL in the bloodstream, "LDL particles will form deposits and accumulate within the arterial walls, which will lead to the development of plaques, restricting blood flow".[48] The resultant reduction in the heart's blood supply due to atherosclerosis in coronary arteries "causes shortness of breath, angina pectoris (chest pains that are usually relieved by rest), and potentially fatal heart attacks (myocardial infarctions)".[35]

Genetics

The heritability of coronary artery disease has been estimated between 40% and 60%.[50] Genome-wide association studies have identified over 160 genetic susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease.[51]

Transcriptome

Transcripts associated with CAD (TRACs) - FoxP1, ICOSLG, IKZF4/Eos, SMYD3, TRIM28, and TCF3/E2A that are likely markers of regulatory T cells (Treg), consistent with known reductions in Tregs in CAD.[52]

The RNA changes are mostly related to ciliary and endocytic transcripts, which in the circulating immune system would be related to the immune synapse. The immune synapse is the contact-dependent mode of communication between T cells and B cells, on one side, and a variety of antigen-presenting and immunomodulating cells on the other side.[53] One of the most differentially expressed genes, fibromodulin (FMOD, increased 2.8-fold in CAD). Several other regulated transcripts encode for proteins related to the structure and function of the immune synapse. Nebulette, the most down-regulated transcript (2.4-fold), is an important 'cytolinker' that connects actin and desmin to facilitate cytoskeletal function and vesicular movement. The endocytic pathway is further modulated by changes in tubulin, which is a key microtubule protein, and fidgetin, which is a tubulin-severing enzyme that is a GWAS marker for cardiovascular risk. Protein recycling would be modulated by changes in the proteasomal regulator SIAH3, and the ubiquitin ligase MARCHF10. On the ciliary aspect of the immune synapse, several of the modulated transcripts are related to ciliary length and function. Steriocilin (STRC) has been studied principally in outer sensory hair cells, and mutations lead to deafness. Steriocilin is a partner to mesothelin (MSN), a related super-helical protein, whose transcript is also modulated in CAD. Likewise, DCDC2, a double-cortin protein, is a known modulator of ciliary length. In the signaling pathways of the immune synapse, there were numerous transcripts that related directly to T cell function and the control of differentiation. Butyrophilin (BTN1A1) is a known co-regulator for T cell activation. Fibromodulin is a well-known modulator of the TGF-beta signaling pathway, which is a primary determinant of Tre differentiation. Further impact on the TGF-beta pathway is reflected in concurrent changes in the BMP receptor 1B RNA (BMPR1B), because the bone morphogenic proteins are members of the TGF-beta superfamily, and likewise impact Treg differentiation. As noted, several of the transcripts (TMEM98, NRCAM, SFRP5, SHISA2) are known elements of the Wnt signaling pathway, which is major determinant of Treg differentiation.

Other

- Endometriosis in females under the age of 40.[54]

- Depression and hostility appear to be risks.[55]

- The number of categories of adverse childhood experiences (psychological, physical, or sexual abuse; violence against mother; or living with household members who used substances, mentally ill, suicidal, or incarcerated) showed a graded correlation with the presence of adult diseases including coronary artery (ischemic heart) disease.[56]

- Hemostatic factors: High levels of fibrinogen and coagulation factor VII are associated with an increased risk of CAD.[57]

- Low hemoglobin.[58]

- In the Asian population, the b fibrinogen gene G-455A polymorphism was associated with the risk of CAD.[59]

- Patient-specific vessel ageing or remodelling determines endothelial cell behaviour and thus disease growth and progression. Such 'hemodynamic markers' are thus patient-specific risk surrogates.[60]

Pathophysiology

Limitation of blood flow to the heart causes ischemia (cell starvation secondary to a lack of oxygen) of the heart's muscle cells. The heart's muscle cells may die from lack of oxygen and this is called a myocardial infarction (commonly referred to as a heart attack). It leads to damage, death, and eventual scarring of the heart muscle without regrowth of heart muscle cells. Chronic high-grade narrowing of the coronary arteries can induce transient ischemia which leads to the induction of a ventricular arrhythmia, which may terminate into a dangerous heart rhythm known as ventricular fibrillation, which often leads to death.[61]

Typically, coronary artery disease occurs when part of the smooth, elastic lining inside a coronary artery (the arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle) develops atherosclerosis. With atherosclerosis, the artery's lining becomes hardened, stiffened, and accumulates deposits of calcium, fatty lipids, and abnormal inflammatory cells – to form a plaque. Calcium phosphate (hydroxyapatite) deposits in the muscular layer of the blood vessels appear to play a significant role in stiffening the arteries and inducing the early phase of coronary arteriosclerosis. This can be seen in a so-called metastatic mechanism of calciphylaxis as it occurs in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis.[citation needed] Although these people have kidney dysfunction, almost fifty percent of them die due to coronary artery disease. Plaques can be thought of as large "pimples" that protrude into the channel of an artery, causing partial obstruction to blood flow. People with coronary artery disease might have just one or two plaques, or might have dozens distributed throughout their coronary arteries. A more severe form is chronic total occlusion (CTO) when a coronary artery is completely obstructed for more than 3 months.[62]

Microvascular angina is a type of angina pectoris in which chest pain and chest discomfort occur without signs of blockages in the larger coronary arteries of their hearts when an angiogram (coronary angiogram) is being performed.[63][64] The exact cause of microvascular angina is unknown. Explanations include microvascular dysfunction or epicardial atherosclerosis.[65][66] For reasons that are not well understood, females are more likely than males to have it; however, hormones and other risk factors unique to females may play a role.[67]

Diagnosis

For symptomatic people, stress echocardiography can be used to make a diagnosis for obstructive coronary artery disease.[68] The use of echocardiography, stress cardiac imaging, and/or advanced non-invasive imaging is not recommended on individuals who are exhibiting no symptoms and are otherwise at low risk for developing coronary disease.[68][69]

The diagnosis of microvascular angina (previously known as cardiac syndrome X – the rare coronary artery disease that is more common in females, as mentioned, is a diagnosis of exclusion. Therefore, usually, the same tests are used as in any person with the suspected of having coronary artery disease:[70]

- Baseline electrocardiography (ECG)

- Exercise ECG – Stress test

- Exercise radioisotope test (nuclear stress test, myocardial scintigraphy)

- Echocardiography (including stress echocardiography)

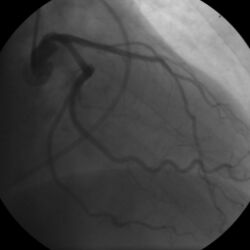

- Coronary angiography

- Intravascular ultrasound

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

The diagnosis of coronary disease underlying particular symptoms depends largely on the nature of the symptoms. The first investigation is an electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG), both for stable angina and acute coronary syndrome. An X-ray of the chest and blood tests may be performed.[71]

Stable angina

Stable angina is the most common form of ischemic heart disease, and is associated with reduced quality of life and increased mortality. It is caused by epicardial coronary stenosis which results in reduced blood flow and oxygen supply to the myocardium.[72] Stable angina is characterized as short-term chest pain during physical exertion caused by an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and metabolic oxygen demand. Various forms of cardiac stress tests may be used to induce both symptoms and detect changes by way of electrocardiography (using an ECG), echocardiography (using ultrasound of the heart) or scintigraphy (using uptake of radionuclide by the heart muscle). If part of the heart seems to receive an insufficient blood supply, coronary angiography may be used to identify stenosis of the coronary arteries and suitability for angioplasty or bypass surgery.[73]

In minor to moderate cases, nitroglycerine may be used to alleviate acute symptoms of stable angina or may be used immediately prior to exertion to prevent the onset of angina. Sublingual nitroglycerine is most commonly used to provide rapid relief for acute angina attacks and as a complement to anti-anginal treatments in patients with refractory and recurrent angina.[74] When nitroglycerine enters the bloodstream, it forms free radical nitric oxide, or NO, which activates guanylate cyclase and in turn stimulates the release of cyclic GMP. This molecular signaling stimulates smooth muscle relaxation, ultimately resulting in vasodilation and consequently improved blood flow to regions of the heart affected by atherosclerotic plaque.[75]

Stable coronary artery disease (SCAD) is also often called stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD).[76] A 2015 monograph explains that "Regardless of the nomenclature, stable angina is the chief manifestation of SIHD or SCAD."[76] There are U.S. and European clinical practice guidelines for SIHD/SCAD.[77][78]

Acute coronary syndrome

Diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome generally takes place in the emergency department, where ECGs may be performed sequentially to identify "evolving changes" (indicating ongoing damage to the heart muscle). Diagnosis is clear-cut if ECGs show elevation of the "ST segment", which in the context of severe typical chest pain is strongly indicative of an acute myocardial infarction (MI); this is termed a STEMI (ST-elevation MI) and is treated as an emergency with either urgent coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (angioplasty with or without stent insertion) or with thrombolysis ("clot buster" medication), whichever is available. In the absence of ST-segment elevation, heart damage is detected by cardiac markers (blood tests that identify heart muscle damage). If there is evidence of damage (infarction), the chest pain is attributed to a "non-ST elevation MI" (NSTEMI). If there is no evidence of damage, the term "unstable angina" is used. This process usually necessitates hospital admission and close observation on a coronary care unit for possible complications (such as cardiac arrhythmias – irregularities in the heart rate). Depending on the risk assessment, stress testing or angiography may be used to identify and treat coronary artery disease in patients who have had an NSTEMI or unstable angina.[citation needed]

Risk assessment

There are various risk assessment systems for determining the risk of coronary artery disease, with various emphasis on different variables above. A notable example is Framingham Score, used in the Framingham Heart Study. It is mainly based on age, gender, diabetes, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, tobacco smoking, and systolic blood pressure. When it comes to predicting risk in younger adults (18–39 years old), Framingham Risk Score remains below 10-12% for all deciles of baseline-predicted risk.[79]

Polygenic score is another way of risk assessment. In one study the relative risk of incident coronary events was 91% higher among participants at high genetic risk than among those at low genetic risk.[80]

Prevention

Up to 90% of cardiovascular disease may be preventable if established risk factors are avoided.[81][82] Prevention involves adequate physical exercise, decreasing obesity, treating high blood pressure, eating a healthy diet, decreasing cholesterol levels, and stopping smoking. Medications and exercise are roughly equally effective.[83] High levels of physical activity reduce the risk of coronary artery disease by about 25%.[84] Life's Essential 8 are the key measures for improving and maintaining cardiovascular health, as defined by the American Heart Association. AHA added sleep as a factor influencing heart health in 2022.[85]

Most guidelines recommend combining these preventive strategies. A 2015 Cochrane Review found some evidence that counseling and education to bring about behavioral change might help in high-risk groups. However, there was insufficient evidence to show an effect on mortality or actual cardiovascular events.[86]

In diabetes mellitus, there is little evidence that very tight blood sugar control improves cardiac risk although improved sugar control appears to decrease other problems such as kidney failure and blindness.[87]

Diet

A diet high in fruits and vegetables decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease and death.[88] Vegetarians have a lower risk of heart disease,[89][90] possibly due to their greater consumption of fruits and vegetables.[91] Evidence also suggests that the Mediterranean diet[92] and a high fiber diet lower the risk.[93][94]

The consumption of trans fat (commonly found in hydrogenated products such as margarine) has been shown to cause a precursor to atherosclerosis[95] and increase the risk of coronary artery disease.[96]

Evidence does not support a beneficial role for omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in preventing cardiovascular disease (including myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death).[97][98] There is tentative evidence that intake of menaquinone (Vitamin K2), but not phylloquinone (Vitamin K1), may reduce the risk of CAD mortality.[99]

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention is preventing further sequelae of already established disease. Effective lifestyle changes include:

- Weight control

- Smoking cessation

- Avoiding the consumption of trans fats (in partially hydrogenated oils)

- Decreasing psychosocial stress[100][101]

- Exercise

Aerobic exercise, like walking, jogging, or swimming, can reduce the risk of mortality from coronary artery disease.[102] Aerobic exercise can help decrease blood pressure and the amount of blood cholesterol (LDL) over time. It also increases HDL cholesterol.[103]

Although exercise is beneficial, it is unclear whether doctors should spend time counseling patients to exercise. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found "insufficient evidence" to recommend that doctors counsel patients on exercise but "it did not review the evidence for the effectiveness of physical activity to reduce chronic disease, morbidity, and mortality", only the effectiveness of counseling itself.[104] The American Heart Association, based on a non-systematic review, recommends that doctors counsel patients on exercise.[105]

Psychological symptoms are common in people with CHD, and while many psychological treatments may be offered following cardiac events, there is no evidence that they change mortality, the risk of revascularization procedures, or the rate of non-fatal myocardial infarction.[101]

Antibiotics for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease

Antibiotics may help patients with coronary disease to reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes.[106] However, the latest evidence suggests that antibiotics for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease are harmful with increased mortality and occurrence of stroke.[106] So, the use of antibiotics is not currently supported for preventing secondary coronary heart disease.

Neuropsychological Assessment

A thorough systematic review found that indeed there is a link between a CHD condition and brain dysfunction in females.[107] Consequently, since research is showing that cardiovascular diseases, like CHD, can play a role as a precursor for dementia, like Alzheimer's disease, individuals with CHD should have a neuropsychological assessment.[108]

Treatment

There are a number of treatment options for coronary artery disease:[109]

- Lifestyle changes

- Medical treatment – commonly prescribed drugs (e.g., cholesterol lowering medications, beta-blockers, nitroglycerin, calcium channel blockers, etc.);

- Coronary interventions as angioplasty and coronary stent;

- Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)

Medications

- Statins, which reduce cholesterol, reduce the risk of coronary artery disease[110]

- Nitroglycerin[111]

- Calcium channel blockers and/or beta-blockers[112]

- Antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin[112][113]

It is recommended that blood pressure typically be reduced to less than 140/90 mmHg.[114] The diastolic blood pressure however should not be lower than 60 mmHg. Beta blockers are recommended first line for this use.[114]

Aspirin

In those with no previous history of heart disease, aspirin decreases the risk of a myocardial infarction but does not change the overall risk of death.[115] Aspirin therapy to prevent heart disease is thus recommended only in adults who are at increased risk for cardiovascular events, which may include postmenopausal females, males above 40, and younger people with risk factors for coronary heart disease, including high blood pressure, a family history of heart disease, or diabetes. The benefits outweigh the harms most favorably in people at high risk for a cardiovascular event, where high risk is defined as at least a 3% chance over a five-year period, but others with lower risk may still find the potential benefits worth the associated risks.[116]

Anti-platelet therapy

Clopidogrel plus aspirin (dual anti-platelet therapy) reduces cardiovascular events more than aspirin alone in those with a STEMI. In others at high risk but not having an acute event, the evidence is weak.[117] Specifically, its use does not change the risk of death in this group.[118] In those who have had a stent, more than 12 months of clopidogrel plus aspirin does not affect the risk of death.[119]

Surgery

Revascularization for acute coronary syndrome has a mortality benefit.[120] Percutaneous revascularization for stable ischaemic heart disease does not appear to have benefits over medical therapy alone.[121] In those with disease in more than one artery, coronary artery bypass grafts appear better than percutaneous coronary interventions.[122] Newer "anaortic" or no-touch off-pump coronary artery revascularization techniques have shown reduced postoperative stroke rates comparable to percutaneous coronary intervention.[123] Hybrid coronary revascularization has also been shown to be a safe and feasible procedure that may offer some advantages over conventional CABG though it is more expensive.[124]

Epidemiology

As of 2010, CAD was the leading cause of death globally resulting in over 7 million deaths.[126] This increased from 5.2 million deaths from CAD worldwide in 1990.[126] It may affect individuals at any age but becomes dramatically more common at progressively older ages, with approximately a tripling with each decade of life.[127] Males are affected more often than females.[127]

It is estimated that 60% of the world's cardiovascular disease burden will occur in the South Asian subcontinent despite only accounting for 20% of the world's population. This may be secondary to a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Organizations such as the Indian Heart Association are working with the World Heart Federation to raise awareness about this issue.[128]

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death for both males and females and accounts for approximately 600,000 deaths in the United States every year.[129] According to present trends in the United States, half of healthy 40-year-old males will develop CAD in the future, and one in three healthy 40-year-old females.[130] It is the most common reason for death of males and females over 20 years of age in the United States.[131]

After analysing data from 2 111 882 patients, the recent meta-analysis revealed that the incidence of coronary artery diseases in breast cancer survicors was 4.29 (95% CI 3.09-5.94) per 1000 person-years.[132]

Society and culture

Names

Other terms sometimes used for this condition are "hardening of the arteries" and "narrowing of the arteries".[133] In Latin it is known as morbus ischaemicus cordis (MIC).

Support groups

The Infarct Combat Project (ICP) is an international nonprofit organization founded in 1998 which tries to decrease ischemic heart diseases through education and research.[134]

Industry influence on research

In 2016 research into the archives of the [failed verification]Sugar Association, the trade association for the sugar industry in the US, had sponsored an influential literature review published in 1965 in the New England Journal of Medicine that downplayed early findings about the role of a diet heavy in sugar in the development of CAD and emphasized the role of fat; that review influenced decades of research funding and guidance on healthy eating.[135][136][137][138]

Research

Research efforts are focused on new angiogenic treatment modalities and various (adult) stem-cell therapies. A region on chromosome 17 was confined to families with multiple cases of myocardial infarction.[139] Other genome-wide studies have identified a firm risk variant on chromosome 9 (9p21.3).[140] However, these and other loci are found in intergenic segments and need further research in understanding how the phenotype is affected.[141]

A more controversial link is that between Chlamydophila pneumoniae infection and atherosclerosis.[142] While this intracellular organism has been demonstrated in atherosclerotic plaques, evidence is inconclusive as to whether it can be considered a causative factor.[143] Treatment with antibiotics in patients with proven atherosclerosis has not demonstrated a decreased risk of heart attacks or other coronary vascular diseases.[144]

Myeloperoxidase has been proposed as a biomarker.[145]

Plant-based nutrition has been suggested as a way to reverse coronary artery disease,[146] but strong evidence is still lacking for claims of potential benefits.[147]

Several immunosuppressive drugs targeting the chronic inflammation in coronary artery disease have been tested.[148]

References

- ↑ "Coronary heart disease – causes, symptoms, prevention". https://www.southerncross.co.nz/AboutTheGroup/HealthResources/MedicalLibrary/tabid/178/vw/1/ItemID/191.

- ↑ "Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease Conference: Executive summary: Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease Conference proceeding for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the American Heart Association". Circulation 109 (21): 2595–604. June 2004. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000128517.52533.DB. PMID 15173041.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Coronary heart disease

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Coronary Heart Disease?". 29 September 2014. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/cad/signs.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)". 12 March 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/coronary_ad.htm.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. World Health Organization. 2011. pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-92-4-156437-3.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Ischemic heart disease in women: a focus on risk factors". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine 25 (2): 140–51. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2014.10.005. PMID 25453985.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "How Is Coronary Heart Disease Diagnosed?". 29 September 2014. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/cad/diagnosis.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "How Can Coronary Heart Disease Be Prevented or Delayed?". http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/cad/prevention.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 "How Is Coronary Heart Disease Treated?". 29 September 2014. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/cad/treatment.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1545–1602. October 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1459–1544. October 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ Biomaterials for clinical applications (Online-Ausg. ed.). New York: Springer. 2010. p. 23. ISBN 9781441969200. https://books.google.com/books?id=bXtaX468LRYC&pg=PA23.

- ↑ "Myocardial ischemia - Symptoms and causes" (in en). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/myocardial-ischemia/symptoms-causes/syc-20375417.

- ↑ "Ischemic Heart Disease". https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/ischemic-heart-disease.

- ↑ Murray, Christopher J. L. (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ "Epidemiological studies of CHD and the evolution of preventive cardiology". Nature Reviews. Cardiology 11 (5): 276–89. May 2014. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2014.26. PMID 24663092.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "The contribution of major depression to the global burden of ischemic heart disease: a comparative risk assessment". BMC Medicine 11: 250. November 2013. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-250. PMID 24274053.

- ↑ Grundy, Scott M.; Stone, Neil J.; Bailey, Alison L.; Beam, Craig; Birtcher, Kim K.; Blumenthal, Roger S.; Braun, Lynne T.; de Ferranti, Sarah et al. (2019-06-25). "2018 Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines" (in en). Journal of the American College of Cardiology 73 (24): e285–e350. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003. ISSN 0735-1097. PMID 30423393.

- ↑ "Screening low-risk individuals for coronary artery disease". Current Atherosclerosis Reports 16 (4): 402. April 2014. doi:10.1007/s11883-014-0402-8. PMID 24522859.

- ↑ "Exercise as a therapeutic intervention in patients with stable ischemic heart disease: an underfilled prescription". The American Journal of Medicine 127 (10): 905–11. October 2014. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.05.007. PMID 24844736.

- ↑ "Coronary artery bypass graft surgery vs percutaneous interventions in coronary revascularization: a systematic review". JAMA 310 (19): 2086–95. November 2013. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281718. PMID 24240936.

- ↑ "Conservative strategy for treatment of stable coronary artery disease". World Journal of Clinical Cases 3 (2): 163–70. February 2015. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i2.163. PMID 25685763.

- ↑ "Temporal trends in ischemic heart disease mortality in 21 world regions, 1980 to 2010: the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study". Circulation 129 (14): 1483–1492. April 2014. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.004042. PMID 24573352.

- ↑ "The global burden of ischemic heart disease in 1990 and 2010: the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study". Circulation 129 (14): 1493–1501. April 2014. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.004046. PMID 24573351.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (October 2011). "Prevalence of coronary heart disease--United States, 2006-2010". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60 (40): 1377–1381. PMID 21993341. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6040a1.htm.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 "Coronary Artery Disease Symptoms: Types, Causes, Risks, Treatment". https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/16821-coronary-artery-disease-symptoms.

- ↑ "Emergency department and office-based evaluation of patients with chest pain". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 85 (3): 284–99. March 2010. doi:10.4065/mcp.2009.0560. PMID 20194155.

- ↑ "Coronary artery disease - Symptoms and causes" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronary-artery-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350613.

- ↑ "Racial differences in women's prodromal and acute symptoms of myocardial infarction". American Journal of Critical Care 19 (1): 63–73. January 2010. doi:10.4037/ajcc2010372. PMID 20045850.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Women's early warning symptoms of acute myocardial infarction". Circulation 108 (21): 2619–23. November 2003. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000097116.29625.7C. PMID 14597589.

- ↑ "Women & Cardiovascular Disease". https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17645-women--cardiovascular-disease.

- ↑ (Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Social Security Cardiovascular Disability Criteria. (2010). Cardiovascular Disability: Updating the Social Security Listings. NCBI, National Academies Press (US). www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209964/#:~:text=Ischemic%20means%20that%20an%20organ,blood%20to%20the%20heart%20muscle)

- ↑ (Tenas, M. S. & Torres, M. F. (2018) What is Ischaemic Heart Disease? Clinic Barcelona. www.clinicbarcelona.org/en/assistance/diseases/ischemic-heart-disease/definition)

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 (Nordestgaard, B. G. & Palmer, T. M. & Benn, M. & Zacho, J & Tybjærg-Hansen, A. & Smith, G. D. & Timpson, N. J. (2012). The Effect of Elevated Body Mass Index on Ischemic Heart Disease Risk: Causal Estimates from a Mendelian Randomisation Approach. PLoS Medicine vol. 9,5 e1001212. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001212)

- ↑ "Genetics of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction". World Journal of Cardiology 8 (1): 1–23. January 2016. doi:10.4330/wjc.v8.i1.1. PMID 26839654.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 "Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data". Lancet 380 (9852): 1491–7. October 2012. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60994-5. PMID 22981903.

- ↑ "Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports". BMJ 360: j5855. January 2018. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5855. PMID 29367388.

- ↑ "Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy". Lancet 380 (9838): 219–29. July 2012. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. PMID 22818936.

- ↑ "Agent Orange presumptive conditions". https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/publications/agent-orange/agent-orange-2020/presumptive.asp.

- ↑ "Traditional Framingham risk factors fail to fully account for accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus". Arthritis and Rheumatism 44 (10): 2331–7. October 2001. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200110)44:10<2331::aid-art395>3.0.co;2-i. PMID 11665973.

- ↑ "How early in the course of rheumatoid arthritis does the excess cardiovascular risk appear?". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 71 (10): 1606–15. October 2012. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201334. PMID 22736093.

- ↑ "The effects of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors, methotrexate, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids on cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 74 (3): 480–9. March 2015. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206624. PMID 25561362.

- ↑ "The Use of Primary Prevention Statin Therapy in Those Predisposed to Atherosclerosis". Current Atherosclerosis Reports 19 (12): 48. October 2017. doi:10.1007/s11883-017-0685-7. PMID 29038899.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Psychosocial stress and atherosclerosis: family and work stress accelerate progression of coronary disease in women. The Stockholm Female Coronary Angiography Study". Journal of Internal Medicine 261 (3): 245–54. March 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01759.x. PMID 17305647.

- ↑ Psychophysiology: human behavior and physiological response. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum. 2000. p. 287.

- ↑ "The precocity-longevity hypothesis: earlier peaks in career achievement predict shorter lives". Pers Soc Psychol Bull 27 (11): 1429–39. November 2001. doi:10.1177/01461672012711004.

"Current issues in Type A behaviour, coronary proneness, and coronary heart disease". Handbook of social and clinical psychology: the health perspective. New York: Pergamon. 1991. pp. 197–220. ISBN 978-0-08-036128-4. https://archive.org/details/handbookofsocial0000unse_f2g8/page/197. - ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 "Lipid Health Risks | BioNinja". https://ib.bioninja.com.au/standard-level/topic-2-molecular-biology/23-carbohydrates-and-lipids/lipid-health-risks.html.

- ↑ "Types of Fatty Acids | BioNinja". https://ib.bioninja.com.au/standard-level/topic-2-molecular-biology/23-carbohydrates-and-lipids/types-of-fatty-acids.html.

- ↑ "Genetics of Coronary Artery Disease". Circulation Research 118 (4): 564–78. February 2016. doi:10.1161/circresaha.115.306566. PMID 26892958.

- ↑ "Identification of 64 Novel Genetic Loci Provides an Expanded View on the Genetic Architecture of Coronary Artery Disease". Circulation Research (Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health)) 122 (3): 433–443. February 2018. doi:10.1161/circresaha.117.312086. PMID 29212778.

- ↑ "RNA sequencing of blood in coronary artery disease: involvement of regulatory T cell imbalance". BMC Med Genomics 14 (216): 216. September 2021. doi:10.1186/s12920-021-01062-2. PMID 34479557.

- ↑ "RNAseq profiling of blood from patients with coronary artery disease: Signature of a T cell imbalance". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology Plus 4: 100033. June 2023. doi:10.1016/j.jmccpl.2023.100033. PMID 37303712.

- ↑ "Endometriosis and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease". Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 9 (3): 257–64. May 2016. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002224. PMID 27025928.

- ↑ "Psychological and social factors in coronary heart disease". Annals of Medicine 42 (7): 487–94. October 2010. doi:10.3109/07853890.2010.515605. PMID 20839918.

- ↑ "Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study". American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14 (4): 245–58. May 1998. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. PMID 9635069.

- ↑ "The genetics of atherothrombotic disorders: a clinician's view". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 1 (7): 1381–90. July 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00276.x. PMID 12871271.

- ↑ "Hemoglobin: Emerging marker in stable coronary artery disease". Chronicles of Young Scientists 2 (2): 109. 2011. doi:10.4103/2229-5186.82971. Gale A261829143. https://ddtjournal.net/?view-pdf=1&embedded=true&article=2acc68c5a97079e54b6b7b584b3de7261Zs4oQ%3D%3D.

- ↑ "The β fibrinogen gene G-455A polymorphism in Asian subjects with coronary heart disease: A meta analysis". Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics 18 (1): 19–28. 2017-02-27. doi:10.1016/j.ejmhg.2016.06.002. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhg/article/view/152188.

- ↑ "A new and automated risk prediction of coronary artery disease using clinical endpoints and medical imaging-derived patient-specific insights: protocol for the retrospective GeoCAD cohort study". British Medical Journal 12 (6): e054881. June 2022. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054881. PMID 35725256.

- ↑ "Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease leading to acute coronary syndromes". F1000Prime Reports 7: 08. 2015. doi:10.12703/P7-08. PMID 25705391.

- ↑ "Chronic total occlusions--a stiff challenge requiring a major breakthrough: is there light at the end of the tunnel?". Heart 91 (Suppl 3): iii42-8. June 2005. doi:10.1136/hrt.2004.058495. PMID 15919653.

- ↑ "Cardiac syndrome X: a critical overview and future perspectives". Heart 93 (2): 159–66. February 2007. doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.067330. PMID 16399854.

- ↑ "Microvascular Angina: Diagnosis and Management". Eur Cardiol 16: e46. February 2021. doi:10.15420/ecr.2021.15. PMID 34950242.

- ↑ "Cardiac syndrome X and microvascular coronary dysfunction". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine 22 (6): 161–8. August 2012. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2012.07.014. PMID 23026403.

- ↑ "Microvascular coronary dysfunction and ischemic heart disease: where are we in 2014?". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine 25 (2): 98–103. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2014.09.013. PMID 25454903.

- ↑ "Pathophysiology and management of patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteriograms (cardiac syndrome X)". Circulation 109 (5): 568–72. February 2004. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000116601.58103.62. PMID 14769677.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 American Society of Echocardiography (20 December 2012). "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: An Initiative of the ABIM Foundation. http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-society-of-echocardiography. Retrieved 27 February 2013., citing

- "ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate Use Criteria for Echocardiography. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 57 (9): 1126–66. March 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.002. PMID 21349406.

- "ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina--summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina)". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 41 (1): 159–68. January 2003. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02848-6. PMID 12570960.

- "2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 56 (25): e50-103. December 2010. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.001. PMID 21144964.

- ↑ American College of Cardiology (September 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation (American College of Cardiology), http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-college-of-cardiology, retrieved 10 February 2014

- ↑ "Cardiac Syndrome X: update 2014". Cardiology Clinics 32 (3): 463–78. August 2014. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2014.04.006. PMID 25091971.

- ↑ "Coronary Artery Disease Diagnosis and Treatment". https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronary-artery-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350619.

- ↑ "Angina - Symptoms and causes" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/angina/symptoms-causes/syc-20369373.

- ↑ "Coronary Angiography". https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/ca.

- ↑ Tarkin, Jason M; Kaski, Juan Carlos (February 2013). "Pharmacological treatment of chronic stable angina pectoris". Clinical Medicine 13 (1): 63–70. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.13-1-63. PMID 23472498.

- ↑ "Nitrostat® (Nitroglycerin Sublingual Tablets, USP)". United States Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021134s004lbl.pdf.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "Overview of ischemic heart disease, stable angina, and drug therapy". Cardiovascular Diseases: From Molecular Pharmacology to Evidence-Based Therapeutics. John Wiley & Sons. 2015. pp. 245–253. ISBN 978-0-470-91537-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=rXy0BgAAQBAJ&pg=PA245.

- ↑ "2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS focused update of the guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons". Circulation 130 (19): 1749–67. November 2014. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000095. PMID 25070666.

- ↑ "ESC Guidelines on Chronic Coronary Syndromes (Previously titled Stable Coronary Artery Disease)". https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Chronic-Coronary-Syndromes.

- ↑ "Framingham risk score and prediction of coronary heart disease death in young men". American Heart Journal 154 (1): 80–6. July 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.042. PMID 17584558.

- ↑ "Genetic Risk, Adherence to a Healthy Lifestyle, and Coronary Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine 375 (24): 2349–2358. December 2016. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1605086. PMID 27959714.

- ↑ "Preventing heart disease in the 21st century: implications of the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) study". Circulation 117 (9): 1216–27. March 2008. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717033. PMID 18316498.

- ↑ "Hypercholesterolemia in youth: opportunities and obstacles to prevent premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease". Current Atherosclerosis Reports 12 (1): 20–8. January 2010. doi:10.1007/s11883-009-0072-0. PMID 20425267.

- ↑ "Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes: metaepidemiological study". BMJ 347 (oct01 1): f5577. October 2013. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5577. PMID 24473061.

- ↑ "Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". BMJ 354: i3857. August 2016. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3857. PMID 27510511.

- ↑ "Life's Essential 8" (in en). https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-lifestyle/lifes-essential-8.

- ↑ "Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001561. January 2011. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001561.pub3. PMID 21249647.

- ↑ Norman, James (2019-10-07). "Managing Diabetes with Blood Glucose Control". https://www.endocrineweb.com/conditions/diabetes/assessing-how-well-diabetes-controlled.

- ↑ "Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". BMJ 349: g4490. July 2014. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4490. PMID 25073782.

- ↑ "Effect of the vegetarian diet on non-communicable diseases". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 94 (2): 169–73. January 2014. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6362. PMID 23965907. Bibcode: 2014JSFA...94..169L.

- ↑ "Cardiovascular disease mortality and cancer incidence in vegetarians: a meta-analysis and systematic review". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism 60 (4): 233–40. 2012. doi:10.1159/000337301. PMID 22677895.

- ↑ "Vegetarian diets, chronic diseases and longevity". Bratislavske Lekarske Listy 109 (10): 463–6. 2008. PMID 19166134.

- ↑ "Diets for cardiovascular disease prevention: what is the evidence?". American Family Physician 79 (7): 571–8. April 2009. PMID 19378874.

- ↑ "Dietary fibre intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ 347: f6879. December 2013. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6879. PMID 24355537.

- ↑ "Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses". Lancet 393 (10170): 434–445. February 2019. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9. PMID 30638909.

- ↑ "Consumption of trans fatty acids is related to plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction". The Journal of Nutrition 135 (3): 562–6. March 2005. doi:10.1093/jn/135.3.562. PMID 15735094.

- ↑ "Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular disease". The New England Journal of Medicine 354 (15): 1601–13. April 2006. doi:10.1056/NEJMra054035. PMID 16611951.

- ↑ "Association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and risk of major cardiovascular disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA 308 (10): 1024–33. September 2012. doi:10.1001/2012.jama.11374. PMID 22968891.

- ↑ "Efficacy of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid) in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials". Archives of Internal Medicine 172 (9): 686–94. May 2012. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.262. PMID 22493407.

- ↑ "Vitamin K intake and atherosclerosis". Current Opinion in Lipidology 19 (1): 39–42. February 2008. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282f1c57f. PMID 18196985.

- ↑ "Psychosocial interventions for patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine 156 (7): 745–52. April 1996. doi:10.1001/archinte.1996.00440070065008. PMID 8615707.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 "Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4 (2): CD002902. April 2017. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002902.pub4. PMID 28452408.

- ↑ "Exercise intervention and inflammatory markers in coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis". American Heart Journal 163 (4): 666–76.e1–3. April 2012. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2011.12.017. PMID 22520533.

- ↑ "Coronary Heart Disease (CHD)". Penguin Dictionary of Biology. 2004. http://www.credoreference.com/entry/penguinbio/coronary_heart_disease_chd.

- ↑ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (August 2002). "Behavioral counseling in primary care to promote physical activity: recommendation and rationale". Annals of Internal Medicine 137 (3): 205–7. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-137-3-200208060-00014. PMID 12160370.

- ↑ "Exercise and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology (Subcommittee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention) and the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Subcommittee on Physical Activity)". Circulation 107 (24): 3109–16. June 2003. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000075572.40158.77. PMID 12821592.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 "Antibiotics for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2 (5): CD003610. February 2021. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003610.pub4. PMID 33704780.

- ↑ "Neuropsychological Sequelae of Coronary Heart Disease in Women: A Systematic Review". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 127: 837–851. August 2021. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.05.026. PMID 34062209.

- ↑ Deckers, Kay; Schievink, Syenna H. J.; Rodriquez, Maria M. F.; Oostenbrugge, Robert J. van; Boxtel, Martin P. J. van; Verhey, Frans R. J.; Köhler, Sebastian (2017-09-08). "Coronary heart disease and risk for cognitive impairment or dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis" (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (9): e0184244. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184244. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28886155. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1284244D.

- ↑ Harrison's principles of internal medicine (16th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. 2005. ISBN 978-0-07-140235-4. OCLC 54501403. http://highered.mcgraw-hill.com/sites/0071402357/information_center_view0. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ "Statin therapy in the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events: a sex-based meta-analysis". Archives of Internal Medicine 172 (12): 909–19. June 2012. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2145. PMID 22732744.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Nitroglycerin Sublingual

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 "CLINICAL PRACTICE. Chronic Stable Angina". The New England Journal of Medicine 374 (12): 1167–76. March 2016. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1502240. PMID 27007960.

- ↑ "Antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 16 (14): 2133–47. 2015. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1079619. PMID 26293612.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 "Treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Society of Hypertension". Circulation 131 (19): e435-70. May 2015. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000207. PMID 25829340.

- ↑ "Aspirin for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine 164 (12): 804–13. June 2016. doi:10.7326/M15-2113. PMID 27064410.

- ↑ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (January 2002). "Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: recommendation and rationale". Annals of Internal Medicine 136 (2): 157–60. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00015. PMID 11790071.

- ↑ "Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for preventing cardiovascular events". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017 (12): CD005158. December 2017. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005158.pub4. PMID 29240976.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA review finds long-term treatment with blood-thinning medicine Plavix (clopidogrel) does not change risk of death". 6 November 2015. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm471286.htm.

- ↑ "Extended duration dual antiplatelet therapy and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet 385 (9970): 792–8. February 2015. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62052-3. PMID 25467565.

- ↑ "ACC/AHA guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction--2002: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina)". Circulation 106 (14): 1893–900. October 2002. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000037106.76139.53. PMID 12356647.

- ↑ "Percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes in patients with stable obstructive coronary artery disease and myocardial ischemia: a collaborative meta-analysis of contemporary randomized clinical trials". JAMA Internal Medicine 174 (2): 232–40. February 2014. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12855. PMID 24296791.

- ↑ "Coronary artery bypass grafting vs percutaneous coronary intervention and long-term mortality and morbidity in multivessel disease: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of the arterial grafting and stenting era". JAMA Internal Medicine 174 (2): 223–30. February 2014. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12844. PMID 24296767.

- ↑ "Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting With and Without Manipulation of the Ascending Aorta: A Network Meta-Analysis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 69 (8): 924–936. February 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.071. PMID 28231944.

- ↑ "Hybrid coronary revascularization versus conventional coronary artery bypass grafting: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Medicine 97 (33): e11941. August 2018. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011941. PMID 30113498.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". 2009. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet 380 (9859): 2095–128. December 2012. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604. PMC 10790329. https://repozitorij.upr.si/Dokument.php?id=7123&dn=.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 "Mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, region, and age: statistics from World Health Organisation and United Nations". International Journal of Cardiology 168 (2): 934–45. September 2013. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.046. PMID 23218570.

- ↑ Indian Heart Association Why South Asians Facts , 29 April 2015; accessed 26 October 2015.

- ↑ "Deaths: final data for 2009". National Vital Statistics Reports 60 (3): 1–116. December 2011. PMID 24974587. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr60/nvsr60_03.pdf.

- ↑ "Heart disease and stroke statistics--2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee". Circulation 115 (5): e69-171. February 2007. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. PMID 17194875.

- ↑ "Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics | American Heart Association (AHA)". 2007. http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3000090.

- ↑ Galimzhanov, Akhmetzhan; Istanbuly, Sedralmontaha; Tun, Han Naung; Ozbay, Benay; Alasnag, Mirvat; Ky, Bonnie; Lyon, Alexander R; Kayikcioglu, Meral et al. (2023-07-27). "Cardiovascular outcomes in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (in en). European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 30 (18): 2018–2031. doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwad243. ISSN 2047-4873. PMID 37499186. https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurjpc/zwad243/7232455.

- ↑ "Other Names for Coronary Heart Disease". 29 September 2014. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/cad/names.

- ↑ "Our Mission". http://www.infarctcombat.org/OurMission.html.

- ↑ O'Connor, Anahad, "How the Sugar Industry Shifted Blame to Fat" , The New York Times, 12 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ "Food Industry Funding of Nutrition Research: The Relevance of History for Current Debates". JAMA Internal Medicine 176 (11): 1685–1686. November 2016. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5400. PMID 27618496.

- ↑ "Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research: A Historical Analysis of Internal Industry Documents". JAMA Internal Medicine 176 (11): 1680–1685. November 2016. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394. PMID 27617709. PMC 5099084. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/09/13/493739074/50-years-ago-sugar-industry-quietly-paid-scientists-to-point-blame-at-fat.

- ↑ "How the sugar industry paid experts to downplay health risks". PBS NewsHour. 13 September 2016. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/sugar-industry-paid-experts-downplay-health-risks/.

- ↑ "Genome-wide mapping of susceptibility to coronary artery disease identifies a novel replicated locus on chromosome 17". PLOS Genetics 2 (5): e72. May 2006. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020072. PMID 16710446.

- ↑ "9p21 and the genetic revolution for coronary artery disease". Clinical Chemistry 58 (1): 104–12. January 2012. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2011.172759. PMID 22015375.

- ↑ "Genomics in coronary artery disease: past, present and future". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology 26 (Suppl A): 56A–59A. March 2010. doi:10.1016/s0828-282x(10)71064-3. PMID 20386763.

- ↑ "Chronic Chlamydia pneumoniae infection as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in the Helsinki Heart Study". Annals of Internal Medicine 116 (4): 273–8. February 1992. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-116-4-273. PMID 1733381.

- ↑ "Infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae as a cause of coronary heart disease: the hypothesis is still untested". Pathogens and Disease 73 (1): 1–9. February 2015. doi:10.1093/femspd/ftu015. PMID 25854002.

- ↑ "Effects of antibiotic therapy on outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". JAMA 293 (21): 2641–7. June 2005. doi:10.1001/jama.293.21.2641. PMID 15928286.

- ↑ "Myeloperoxidase: a new biomarker of inflammation in ischemic heart disease and acute coronary syndromes". Mediators of Inflammation 2008: 135625. 2008. doi:10.1155/2008/135625. PMID 18382609.

- ↑ "A way to reverse CAD?". The Journal of Family Practice 63 (7): 356–364b. July 2014. PMID 25198208. https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/JFP_06307_Article1.pdf.

- ↑ "Trending Cardiovascular Nutrition Controversies". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 69 (9): 1172–1187. March 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.086. PMID 28254181.

- ↑ "Immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive therapies in cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A bedside-to-bench approach". Eur J Pharmacol 925: 174998. 2022. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.174998. PMID 35533739.

External links

- Risk Assessment of having a heart attack or dying of coronary artery disease, from the American Heart Association.

- "Coronary Artery Disease". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/coronaryarterydisease.html.

- Norman, James (2019-10-07). "Managing Diabetes with Blood Glucose Control". https://www.endocrineweb.com/conditions/diabetes/assessing-how-well-diabetes-controlled.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|