Biology:Adenomatous polyposis coli

Generic protein structure example |

Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) also known as deleted in polyposis 2.5 (DP2.5) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the APC gene.[1] The APC protein is a negative regulator that controls beta-catenin concentrations and interacts with E-cadherin, which are involved in cell adhesion. Mutations in the APC gene may result in colorectal cancer and desmoid tumors.[2][3]

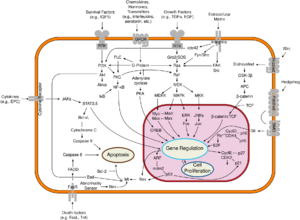

APC is classified as a tumor suppressor gene. Tumor suppressor genes prevent the uncontrolled growth of cells that may result in cancerous tumors. The protein made by the APC gene plays a critical role in several cellular processes that determine whether a cell may develop into a tumor. The APC protein helps control how often a cell divides, how it attaches to other cells within a tissue, how the cell polarizes and the morphogenesis of the 3D structures,[4] or whether a cell moves within or away from tissue. This protein also helps ensure that the chromosome number in cells produced through cell division is correct. The APC protein accomplishes these tasks mainly through association with other proteins, especially those that are involved in cell attachment and signaling. The activity of one protein in particular, beta-catenin, is controlled by the APC protein (see: Wnt signaling pathway). Regulation of beta-catenin prevents genes that stimulate cell division from being turned on too often and prevents cell overgrowth.

The human APC gene is located on the long (q) arm of chromosome 5 in band q22.2 (5q22.2). The APC gene has been shown to contain an internal ribosome entry site. APC orthologs[5] have also been identified in all mammals for which complete genome data are available.

Structure

The full-length human protein comprises 2,843 amino acids with a (predicted) molecular mass of 311646 Da. Several N-terminal domains have been structurally elucidated in unique atomistic high-resolution complex structures. Most of the protein is predicted to be intrinsically disordered. It is not known if this large predicted unstructured region from amino acid 800 to 2843 persists in vivo or would form stabilised complexes – possibly with yet unidentified interacting proteins.[6] Recently, it has been experimentally confirmed that the mutation cluster region around the center of APC is intrinsically disordered in vitro.[7]

Role in cancer

The most common mutation in colon cancer is inactivation of APC. In absence of APC inactivating mutations, colon cancers commonly carry activating mutations in beta catenin or inactivating mutations in RNF43.[8] Mutations in APC can be inherited, or arise sporadically in the somatic cells, often as the result of mutations in other genes that result in the inability to repair mutations in the DNA. In order for cancer to develop, both alleles (copies of the APC gene) must be mutated. Mutations in APC or β-catenin must be followed by other mutations to become cancerous; however, in carriers of an APC-inactivating mutation, the risk of colorectal cancer by age 40 is almost 100%.[2]

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is caused by an inherited, inactivating mutation in the APC gene.[9] More than 800 mutations [citation needed] in the APC gene have been identified in families with classic and attenuated types of familial adenomatous polyposis. Most of these mutations cause the production of an APC protein that is abnormally short and presumably nonfunctional. This short protein cannot suppress the cellular overgrowth that leads to the formation of polyps, which can become cancerous. The most common mutation in familial adenomatous polyposis is a deletion of five bases in the APC gene. This mutation changes the sequence of amino acids in the resulting APC protein beginning at position 1309. Mutations in the APC gene have also been found to lead to the development of desmoid tumors in FAP patients.[3]

Another mutation is carried by approximately 6 percent[citation needed] of people of Ashkenazi (eastern and central European) Jewish heritage. This mutation results in the substitution of the amino acid lysine for isoleucine at position 1307 in the APC protein (also written as I1307K or Ile1307Lys). This change has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of colon cancer,[10] with moderate effect size.[11] APC I1307K has also been implicated as a risk factor for certain other cancers.[11]

Regulation of proliferation

The (Adenomatous Polyposis Coli) APC protein normally builds a "destruction complex" with glycogen synthase kinase 3-alpha and or beta (GSK-3α/β) and Axin via interactions with the 20 AA and SAMP repeats.[12][13][14] This complex is then able to bind β-catenins in the cytoplasm, that have dissociated from adherens contacts between cells. With the help of casein kinase 1 (CK1), which carries out an initial phosphorylation of β-catenin, GSK-3β is able to phosphorylate β-catenin a second time. This targets β-catenin for ubiquitination and degradation by cellular proteasomes. This prevents it from translocating into the nucleus, where it acts as a transcription factor for proliferation genes.[15] APC is also thought to be targeted to microtubules via the PDZ binding domain, stabilizing them.[16] The deactivation of the APC protein can take place after certain chain reactions in the cytoplasm are started, e.g. through the Wnt signals that destroy the conformation of the complex.[citation needed] In the nucleus it complexes with legless/BCL9, TCF, and Pygo.[citation needed]

The ability of APC to bind β-catenin has been classically considered to be an integral part of the protein's mechanistic function in the destruction complex, along with binding to Axin through the SAMP repeats.[17] These models have been substantiated by observations that common APC loss of function mutations in the mutation cluster region often remove several β-catenin binding sites and SAMP repeats. However, recent evidence from Yamulla and colleagues have directly tested those models and imply that APC's core mechanistic functions may not require direct binding to β-catenin, but necessitate interactions with Axin.[18] The researchers hypothesized that APC's many β-catenin binding sites increase the protein's efficiency at destroying β-catenin, yet are not absolutely necessary for the protein's mechanistic function. Further research is clearly necessary to elucidate the precise mechanistic function of APC in the destruction complex.

Mutations

Mutations in APC often occur early on in cancers such as colon cancer.[6] Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) have germline mutations, with 95% being nonsense/frameshift mutations leading to premature stop codons. 33% of mutations occur between amino acids 1061–1309. In somatic mutations, over 60% occur within a mutation cluster region (1286–1513), causing loss of axin-binding sites in all but one of the 20AA repeats. Mutations in APC lead to loss of β-catenin regulation, altered cell migration and chromosome instability.[8]

Neurological role

Rosenberg et al. found that APC directs cholinergic synapse assembly between neurons, a finding with implications for autonomic neuropathies, for Alzheimer's disease, for age-related hearing loss, and for some forms of epilepsy and schizophrenia.[19] (29)

Interactions

APC (gene) has been shown to interact with:

- ARHGEF4,[20]

- AXIN1,[14]

- BUB1,[21]

- CTNNB1,[22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

- CSNK2B,[27]

- CSNK2A1,[27]

- Catenin (cadherin-associated protein), alpha 1,[22][30]

- DLG3,[31]

- KIFAP3,[32]

- MAPRE2,[33][34]

- JUP,[30][35]

- SIAH1,[36]

- TFAP2A,[37]

- TUBA4A[38] and

- XPO1.[39]

See also

- MUTYH

References

- ↑ "Mutations of chromosome 5q21 genes in FAP and colorectal cancer patients". Science 253 (5020): 665–669. August 1991. doi:10.1126/science.1651563. PMID 1651563. Bibcode: 1991Sci...253..665N.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine 361 (25): 2449–2460. December 2009. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804588. PMID 20018966.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Intra-Abdominal and Abdominal Wall Desmoid Fibromatosis". Oncology and Therapy 4 (1): 57–72. June 2016. doi:10.1007/s40487-016-0017-z. PMID 28261640.

- ↑ "The APC tumor suppressor is required for epithelial cell polarization and three-dimensional morphogenesis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1853 (3): 711–723. March 2015. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.12.036. PMID 25578398.

- ↑ "OrthoMaM phylogenetic marker: APC coding sequence". http://www.orthomam.univ-montp2.fr/orthomam/data/cds/detailMarkers/ENSG00000134982_APC.xml.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Messing up disorder: how do missense mutations in the tumor suppressor protein APC lead to cancer?". Molecular Cancer 10: 101. August 2011. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-10-101. PMID 21859464.

- ↑ "Large extent of disorder in Adenomatous Polyposis Coli offers a strategy to guard Wnt signalling against point mutations". PLOS ONE 8 (10): e77257. 2013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077257. PMID 24130866. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...877257M.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Mutations and mechanisms of WNT pathway tumour suppressors in cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer 21 (1): 5–21. January 2021. doi:10.1038/s41568-020-00307-z. PMID 33097916.

- ↑ "Familial Adenomatous Polyposis". https://www.lecturio.com/concepts/familial-adenomatous-polyposis/.

- ↑ "APC polymorphisms and the risk of colorectal neoplasia: a HuGE review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Epidemiology 177 (11): 1169–1179. June 2013. doi:10.1093/aje/kws382. PMID 23576677.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Ashkenazi Jewish and Other White APC I1307K Carriers Are at Higher Risk for Multiple Cancers". Cancers 14 (23): 5875. November 2022. doi:10.3390/cancers14235875. 5875. PMID 36497357.

- ↑ "Binding of GSK3beta to the APC-beta-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly". Science 272 (5264): 1023–1026. May 1996. doi:10.1126/science.272.5264.1023. PMID 8638126. Bibcode: 1996Sci...272.1023R.

- ↑ "Axin, a negative regulator of the wnt signaling pathway, directly interacts with adenomatous polyposis coli and regulates the stabilization of beta-catenin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 (18): 10823–10826. May 1998. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.18.10823. PMID 9556553.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Axin, an inhibitor of the Wnt signalling pathway, interacts with beta-catenin, GSK-3beta and APC and reduces the beta-catenin level". Genes to Cells 3 (6): 395–403. June 1998. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00198.x. PMID 9734785.

- ↑ "Molecular principles of cancer invasion and metastasis (review)". International Journal of Oncology 34 (4): 881–895. April 2009. doi:10.3892/ijo_00000214. PMID 19287945.

- ↑ "EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration". Nature Cell Biology 6 (9): 820–830. September 2004. doi:10.1038/ncb1160. PMID 15311282.

- ↑ "The β-catenin destruction complex". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 5 (1): a007898. January 2013. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a007898. PMID 23169527.

- ↑ "Testing models of the APC tumor suppressor/β-catenin interaction reshapes our view of the destruction complex in Wnt signaling". Genetics 197 (4): 1285–1302. August 2014. doi:10.1534/genetics.114.166496. PMID 24931405.

- ↑ "The postsynaptic adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) multiprotein complex is required for localizing neuroligin and neurexin to neuronal nicotinic synapses in vivo". The Journal of Neuroscience 30 (33): 11073–11085. August 2010. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0983-10.2010. PMID 20720115.

- ↑ "Asef, a link between the tumor suppressor APC and G-protein signaling". Science 289 (5482): 1194–1197. August 2000. doi:10.1126/science.289.5482.1194. PMID 10947987. Bibcode: 2000Sci...289.1194K.

- ↑ "A role for the Adenomatous Polyposis Coli protein in chromosome segregation". Nature Cell Biology 3 (4): 429–432. April 2001. doi:10.1038/35070123. PMID 11283619.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Association of the APC tumor suppressor protein with catenins". Science 262 (5140): 1734–1737. December 1993. doi:10.1126/science.8259519. PMID 8259519. Bibcode: 1993Sci...262.1734S.

- ↑ "Expression and interaction of different catenins in colorectal carcinoma cells". International Journal of Molecular Medicine 8 (6): 695–698. December 2001. doi:10.3892/ijmm.8.6.695. PMID 11712088.

- ↑ "Differences between the interaction of beta-catenin with non-phosphorylated and single-mimicked phosphorylated 20-amino acid residue repeats of the APC protein". Journal of Molecular Biology 327 (2): 359–367. March 2003. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00144-X. PMID 12628243.

- ↑ "The interaction between beta-catenin, GSK3beta and APC after motogen induced cell-cell dissociation, and their involvement in signal transduction pathways in prostate cancer". International Journal of Oncology 18 (4): 843–847. April 2001. doi:10.3892/ijo.18.4.843. PMID 11251183.

- ↑ "Pin1 regulates turnover and subcellular localization of beta-catenin by inhibiting its interaction with APC". Nature Cell Biology 3 (9): 793–801. September 2001. doi:10.1038/ncb0901-793. PMID 11533658.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 "Association and regulation of casein kinase 2 activity by adenomatous polyposis coli protein". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (9): 5959–5964. April 2002. doi:10.1073/pnas.092143199. PMID 11972058. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.5959K.

- ↑ "DAP-1, a novel protein that interacts with the guanylate kinase-like domains of hDLG and PSD-95". Genes to Cells 2 (6): 415–424. June 1997. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1310329.x. PMID 9286858.

- ↑ "Molecular mechanisms of beta-catenin recognition by adenomatous polyposis coli revealed by the structure of an APC-beta-catenin complex". The EMBO Journal 20 (22): 6203–6212. November 2001. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.22.6203. PMID 11707392.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "The tyrosine kinase substrate p120cas binds directly to E-cadherin but not to the adenomatous polyposis coli protein or alpha-catenin". Molecular and Cellular Biology 15 (9): 4819–4824. September 1995. doi:10.1128/mcb.15.9.4819. PMID 7651399.

- ↑ "Cloning and characterization of NE-dlg: a novel human homolog of the Drosophila discs large (dlg) tumor suppressor protein interacts with the APC protein". Oncogene 14 (20): 2425–2433. May 1997. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201087. PMID 9188857.

- ↑ "Identification of a link between the tumour suppressor APC and the kinesin superfamily". Nature Cell Biology 4 (4): 323–327. April 2002. doi:10.1038/ncb779. PMID 11912492.

- ↑ "APC binds to the novel protein EB1". Cancer Research 55 (14): 2972–2977. July 1995. PMID 7606712.

- ↑ "Critical role for the EB1 and APC interaction in the regulation of microtubule polymerization". Current Biology 11 (13): 1062–1067. July 2001. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00297-4. PMID 11470413.

- ↑ "Association of plakoglobin with APC, a tumor suppressor gene product, and its regulation by tyrosine phosphorylation". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 203 (1): 519–522. August 1994. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1994.2213. PMID 8074697.

- ↑ "Siah-1 mediates a novel beta-catenin degradation pathway linking p53 to the adenomatous polyposis coli protein". Molecular Cell 7 (5): 927–936. May 2001. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00241-6. PMID 11389840.

- ↑ "Activator protein 2alpha associates with adenomatous polyposis coli/beta-catenin and Inhibits beta-catenin/T-cell factor transcriptional activity in colorectal cancer cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (44): 45669–45675. October 2004. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405025200. PMID 15331612.

- ↑ "Binding of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein to microtubules increases microtubule stability and is regulated by GSK3 beta phosphorylation". Current Biology 11 (1): 44–49. January 2001. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00002-1. PMID 11166179.

- ↑ "The coiled coil region (amino acids 129-250) of the tumor suppressor protein adenomatous polyposis coli (APC). Its structure and its interaction with chromosome maintenance region 1 (Crm-1)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (35): 32332–32338. August 2002. doi:10.1074/jbc.M203990200. PMID 12070164.

Further reading

- "Molecular dimensions of gastrointestinal tumors: some thoughts for digestion". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A 122A (4): 303–314. November 2003. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20473. PMID 14518068.

- "The ABC of APC". Human Molecular Genetics 10 (7): 721–733. April 2001. doi:10.1093/hmg/10.7.721. PMID 11257105.

- "The APC gene in colorectal cancer". European Journal of Cancer 38 (7): 867–871. May 2002. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00040-0. PMID 11978510.

- "Biology of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor". Journal of Clinical Oncology 18 (9): 1967–1979. May 2000. doi:10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.1967. PMID 10784639.

- "The complex genotype-phenotype relationship in familial adenomatous polyposis". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 16 (1): 5–8. January 2004. doi:10.1097/00042737-200401000-00002. PMID 15095846.

- "Familial adenomatous polyposis". Seminars in Surgical Oncology 18 (4): 314–323. June 2000. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2388(200006)18:4<314::AID-SSU6>3.0.CO;2-9. PMID 10805953.

- "The many faces of the tumor suppressor gene APC". Experimental Cell Research 264 (1): 126–134. March 2001. doi:10.1006/excr.2000.5142. PMID 11237529.

- "Adenomatous polyposis coli plays a key role, in vivo, in coordinating assembly of the neuronal nicotinic postsynaptic complex". Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences 38 (2): 138–152. June 2008. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2008.02.006. PMID 18407517.

External links

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on APC-Associated Polyposis Conditions

- OMIM entries on APC-Associated Polyposis Conditions

- Adenomatous+Polyposis+Coli+Protein at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- GeneCard

- Database concerning peer-reviewed reports on cancer critical alteration in several genes including (APC (protein)), (TP53), (Beta-catenin|β-catenin)

- Human APC genome location and APC gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

|