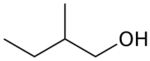

Chemistry:2-Methyl-1-butanol

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Methylbutan-1-ol | |

| Other names

2-Methyl-1-butanol

Active amyl alcohol | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H12O | |

| Molar mass | 88.148 g/mol |

| Appearance | colorless liquid |

| Density | 0.8152 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | −117.2 °C (−179.0 °F; 156.0 K) |

| Boiling point | 127.5 °C (261.5 °F; 400.6 K) |

| 31 g/L | |

| Solubility | organic solvents |

| Vapor pressure | 3 mm Hg |

| Viscosity | 4.453 mPa·s |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

-356.6 kJ·mol−1 (liquid) -301.4 kJ·mol−1 (gas) |

| Hazards | |

| 385 °C (725 °F; 658 K) | |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

Amyl alcohol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

2-Methyl-1-butanol (IUPAC name, also called active amyl alcohol) is an organic compound with the formula CH3CH2CH(CH3)CH2OH. It is one of several isomers of amyl alcohol. This colorless liquid occurs naturally in trace amounts and has attracted some attention as a potential biofuel, exploiting its hydrophobic (gasoline-like) and branched structure. It is chiral.[3]

Occurrence

2-Methyl-1-butanol is a component of many mixtures of commercial amyl alcohols. It is one of the many components of the aroma of various fungi and fruit, e.g., the summer truffle, tomato,[4] and cantaloupe.[5][6]

Production and reactions

2-Methyl-1-butanol has been produced from glucose by genetically modified E. coli. 2-Keto-3-methylvalerate, a precursor to threonine, is converted to the target alcohol by the sequential action of 2-keto acid decarboxylase and dehydrogenase.[7] It can be derived from fusel oil (because it occurs naturally in fruits such as grapes[8]) or manufactured by either the oxo process or via the halogenation of pentane.[2]

See also

- 2-Methyl-2-butanol

References

- ↑ Lide, David R. (1998), Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87 ed.), Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, pp. 3–374, 5–42, 6–188, 8–102, 16–22, ISBN 0-8493-0594-2

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McKetta, John J.; Cunningham, William Aaron (1977), Encyclopedia of Chemical Processing and Design, 3, Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, pp. 279–280, ISBN 978-0-8247-2480-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=iwSU5G5VzO0C&pg=PA279, retrieved 2009-12-14

- ↑ Xiong, Ren-Gen; You, Xiao-Zeng; Abrahams, Brendan F.; Xue, Ziling; Che, Chi-Ming (2001). "Enantioseparation of Racemic Organic Molecules by a Zeolite Analogue". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 40 (23): 4422–4425. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20011203)40:23<4422::AID-ANIE4422>3.0.CO;2-G. PMID 12404434.

- ↑ Buttery, Ron G.; Teranishi, Roy; Ling, Louisa C. (1987). "Fresh tomato aroma volatiles: A quantitative study". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 35 (4): 540–544. doi:10.1021/jf00076a025.

- ↑ Dı́Az, P.; Ibáñez, E.; Señoráns, F.J; Reglero, G. (2003). "Truffle Aroma Characterization by Headspace solid-phase microextraction". Journal of Chromatography A 1017 (1–2): 207–214. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2003.08.016. PMID 14584705.

- ↑ Beaulieu, John C.; Grimm, Casey C. (2001). "Identification of Volatile Compounds in Cantaloupe at Various Developmental Stages Using Solid Phase Microextraction". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 49 (3): 1345–1352. doi:10.1021/jf0005768. PMID 11312862.

- ↑ Atsumi, Shota; Hanai, Taizo; Liao, James C. (2008). "Non-Fermentative Pathways for Synthesis of Branched-Chain Higher Alcohols as Biofuels". Nature 451 (7174): 86–89. doi:10.1038/nature06450. PMID 18172501. Bibcode: 2008Natur.451...86A.

- ↑ Howard, Philip H. (1993), Handbook of Environmental Fate and Exposure Data for Organic Chemicals, 4, Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, pp. 392–396, ISBN 978-0-87371-413-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=HdhohbQrg8IC&pg=PA392, retrieved 2009-12-14

|