Medicine:Urinary tract infection

| Urinary tract infection | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acute cystitis, simple cystitis, bladder infection, symptomatic bacteriuria |

| |

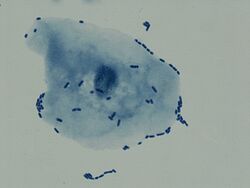

| Multiple white cells seen in the urine of a person with a urinary tract infection using microscopy | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, Urology |

| Symptoms | Pain with urination, frequent urination, feeling the need to urinate despite having an empty bladder[1] |

| Causes | Most often Escherichia coli[2] |

| Risk factors | Catheterisation (foley catheter), female anatomy, sexual intercourse, diabetes, obesity, family history[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, urine culture[3][4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Vulvovaginitis, urethritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, interstitial cystitis,[5] kidney stone disease[6] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics (nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole)[7] |

| Frequency | 152 million (2015)[8] |

| Deaths | 196,500 (2015)[9] |

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection that affects a part of the urinary tract.[1] When it affects the lower urinary tract it is known as a bladder infection (cystitis) and when it affects the upper urinary tract it is known as a kidney infection (pyelonephritis).[10] Symptoms from a lower urinary tract infection include pain with urination, frequent urination, and feeling the need to urinate despite having an empty bladder.[1] Symptoms of a kidney infection include fever and flank pain usually in addition to the symptoms of a lower UTI.[10] Rarely the urine may appear bloody.[7] In the very old and the very young, symptoms may be vague or non-specific.[1][11]

The most common cause of infection is Escherichia coli, though other bacteria or fungi may sometimes be the cause.[2] Risk factors include female anatomy, sexual intercourse, diabetes, obesity, and family history.[2] Although sexual intercourse is a risk factor, UTIs are not classified as sexually transmitted infections (STIs).[12] Pyelonephritis usually occurs due to a bladder infection but may also result from a blood-borne bacterial infection.[13] Diagnosis in young healthy women can be based on symptoms alone.[4] In those with vague symptoms, diagnosis can be difficult because bacteria may be present without there being an infection.[14] In complicated cases or if treatment fails, a urine culture may be useful.[3]

In uncomplicated cases, UTIs are treated with a short course of antibiotics such as nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.[7] Resistance to many of the antibiotics used to treat this condition is increasing.[1] In complicated cases, a longer course or intravenous antibiotics may be needed.[7] If symptoms do not improve in two or three days, further diagnostic testing may be needed.[3] Phenazopyridine may help with symptoms.[1] In those who have bacteria or white blood cells in their urine but have no symptoms, antibiotics are generally not needed,[15] although during pregnancy is an exception.[16] In those with frequent infections, a short course of antibiotics may be taken as soon as symptoms begin or long-term antibiotics may be used as a preventive measure.[17]

About 150 million people develop a urinary tract infection in a given year.[2] They are more common in women than men, but similar between anatomies while carrying indwelling catheters.[7][18] In women, they are the most common form of bacterial infection.[19] Up to 10% of women have a urinary tract infection in a given year, and half of women have at least one infection at some point in their lifetime.[4][7] They occur most frequently between the ages of 16 and 35 years.[7] Recurrences are common.[7] Urinary tract infections have been described since ancient times with the first documented description in the Ebers Papyrus dated to c. 1550 BC.[20] File:En.Wikipedia-VideoWiki-Urinary tract infection.webm

Signs and symptoms

Lower urinary tract infection is also referred to as a bladder infection. The most common symptoms are burning with urination and having to urinate frequently (or an urge to urinate) in the absence of vaginal discharge and significant pain.[4] These symptoms may vary from mild to severe[10] and in healthy women last an average of six days.[19] Some pain above the pubic bone or in the lower back may be present. People experiencing an upper urinary tract infection, or pyelonephritis, may experience flank pain, fever, or nausea and vomiting in addition to the classic symptoms of a lower urinary tract infection.[10] Rarely, the urine may appear bloody[7] or contain visible pus in the urine.[21]

UTIs have been associated with onset or worsening of delirium, dementia, and neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression and psychosis. However, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether UTI causes confusion.[22][23][24][25] The reasons for this are unknown, but may involve a UTI-mediated systemic inflammatory response which affects the brain.[22][23][26][27] Cytokines such as interleukin-6 produced as part of the inflammatory response may produce neuroinflammation, in turn affecting dopaminergic and/or glutamatergic neurotransmission as well as brain glucose metabolism.[22][23][26][27]

Children

In young children, the only symptom of a urinary tract infection (UTI) may be a fever.[28] Because of the lack of more obvious symptoms, when females under the age of two or uncircumcised males less than a year exhibit a fever, a culture of the urine is recommended by many medical associations.[28] Infants may feed poorly, vomit, sleep more, or show signs of jaundice.[28] In older children, new onset urinary incontinence (loss of bladder control) may occur.[28] About 1 in 400 infants of one to three months of age with a UTI also have bacterial meningitis.[29]

Elderly

Urinary tract symptoms are frequently lacking in the elderly.[11] The presentations may be vague with incontinence, a change in mental status, or fatigue as the only symptoms,[10] while some present to a health care provider with sepsis, an infection of the blood, as the first symptoms.[7] Diagnosis can be complicated by the fact that many elderly people have preexisting incontinence or dementia.[11]

It is reasonable to obtain a urine culture in those with signs of systemic infection that may be unable to report urinary symptoms, such as when advanced dementia is present.[30] Systemic signs of infection include a fever or increase in temperature of more than 1.1 °C (2.0 °F) from usual, chills, and an increased white blood cell count.[30]

Cause

Uropathogenic E. coli from the gut is the cause of 80–85% of community-acquired urinary tract infections,[31] with Staphylococcus saprophyticus being the cause in 5–10%.[4] Rarely they may be due to viral or fungal infections.[32] Healthcare-associated urinary tract infections (mostly related to urinary catheterization) involve a much broader range of pathogens including: E. coli (27%), Klebsiella (11%), Pseudomonas (11%), the fungal pathogen Candida albicans (9%), and Enterococcus (7%) among others.[7][33][34] Urinary tract infections due to Staphylococcus aureus typically occur secondary to blood-borne infections.[10] Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium can infect the urethra but not the bladder.[35] These infections are usually classified as a urethritis rather than urinary tract infection.[36]

Intercourse

In young sexually active women, sexual activity is the cause of 75–90% of bladder infections, with the risk of infection related to the frequency of sex.[4] The term "honeymoon cystitis" has been applied to this phenomenon of frequent UTIs during early marriage. In post-menopausal women, sexual activity does not affect the risk of developing a UTI.[4] Spermicide use, independent of sexual frequency, increases the risk of UTIs.[4] Diaphragm use is also associated.[37] Condom use without spermicide or use of birth control pills does not increase the risk of uncomplicated urinary tract infection.[4][38]

Sex

Women are more prone to UTIs than men because, in females, the urethra is much shorter and closer to the anus.[39] As a woman's estrogen levels decrease with menopause, her risk of urinary tract infections increases due to the loss of protective vaginal flora.[39] Additionally, vaginal atrophy that can sometimes occur after menopause is associated with recurrent urinary tract infections.[40]

Chronic prostatitis in the forms of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and chronic bacterial prostatitis (not acute bacterial prostatitis or asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis) may cause recurrent urinary tract infections in males. Risk of infections increases as males age. While bacteria is commonly present in the urine of older males this does not appear to affect the risk of urinary tract infections.[41]

Urinary catheters

Urinary catheterization increases the risk for urinary tract infections. The risk of bacteriuria (bacteria in the urine) is between three and six percent per day and prophylactic antibiotics are not effective in decreasing symptomatic infections.[39] The risk of an associated infection can be decreased by catheterizing only when necessary, using aseptic technique for insertion, and maintaining unobstructed closed drainage of the catheter.[42][43][44]

Male scuba divers using condom catheters and female divers using external catching devices for their dry suits are also susceptible to urinary tract infections.[45]

Others

A predisposition for bladder infections may run in families.[4] This is believed to be related to genetics.[4] Other risk factors include diabetes,[4] being uncircumcised,[46][47] and having a large prostate.[10] In children UTIs are associated with vesicoureteral reflux (an abnormal movement of urine from the bladder into ureters or kidneys) and constipation.[28]

Persons with spinal cord injury are at increased risk for urinary tract infection in part because of chronic use of catheter, and in part because of voiding dysfunction.[48] It is the most common cause of infection in this population, as well as the most common cause of hospitalization.[48]

Pathogenesis

The bacteria that cause urinary tract infections typically enter the bladder via the urethra. However, infection may also occur via the blood or lymph.[7] It is believed that the bacteria are usually transmitted to the urethra from the bowel, with females at greater risk due to their anatomy.[7] After gaining entry to the bladder, E. Coli are able to attach to the bladder wall and form a biofilm that resists the body's immune response.[7]

Escherichia coli is the single most common microorganism, followed by Klebsiella and Proteus spp., to cause urinary tract infection. Klebsiella and Proteus spp., are frequently associated with stone disease. The presence of Gram positive bacteria such as Enterococcus and Staphylococcus is increased.[49]

The increased resistance of urinary pathogens to quinolone antibiotics has been reported worldwide and might be the consequence of overuse and misuse of quinolones.[49]

Diagnosis

In straightforward cases, a diagnosis may be made and treatment given based on symptoms alone without further laboratory confirmation.[4] In complicated or questionable cases, it may be useful to confirm the diagnosis via urinalysis, looking for the presence of urinary nitrites, white blood cells (leukocytes), or leukocyte esterase.[50] Another test, urine microscopy, looks for the presence of red blood cells, white blood cells, or bacteria. Urine culture is deemed positive if it shows a bacterial colony count of greater than or equal to 103 colony-forming units per mL of a typical urinary tract organism. Antibiotic sensitivity can also be tested with these cultures, making them useful in the selection of antibiotic treatment. However, women with negative cultures may still improve with antibiotic treatment.[4] As symptoms can be vague and without reliable tests for urinary tract infections, diagnosis can be difficult in the elderly.[11]

Based on pH

Normal urine pH is slightly acidic, with usual values of 6.0 to 7.5, but the normal range is 4.5 to 8.0. A urine pH of 8.5 or 9.0 is indicative of a urea-splitting organism, such as Proteus, Klebsiella, or Ureaplasma urealyticum; therefore, an asymptomatic patient with a high pH means UTI regardless of the other urine test results. Alkaline pH also can signify struvite kidney stones, which are also known as "infection stones".[6]

Classification

A urinary tract infection may involve only the lower urinary tract, in which case it is known as a bladder infection. Alternatively, it may involve the upper urinary tract, in which case it is known as pyelonephritis. If the urine contains significant bacteria but there are no symptoms, the condition is known as asymptomatic bacteriuria.[10] If a urinary tract infection involves the upper tract, and the person has diabetes mellitus, is pregnant, is male, or immunocompromised, it is considered complicated.[7][19] Otherwise if a woman is healthy and premenopausal it is considered uncomplicated.[19] In children when a urinary tract infection is associated with a fever, it is deemed to be an upper urinary tract infection.[28]

Children

To make the diagnosis of a urinary tract infection in children, a positive urinary culture is required. Contamination poses a frequent challenge depending on the method of collection used, thus a cutoff of 105 CFU/mL is used for a "clean-catch" mid stream sample, 104 CFU/mL is used for catheter-obtained specimens, and 102 CFU/mL is used for suprapubic aspirations (a sample drawn directly from the bladder with a needle). The use of "urine bags" to collect samples is discouraged by the World Health Organization due to the high rate of contamination when cultured, and catheterization is preferred in those not toilet trained. Some, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends renal ultrasound and voiding cystourethrogram (watching a person's urethra and urinary bladder with real time x-rays while they urinate) in all children less than two years old who have had a urinary tract infection. However, because there is a lack of effective treatment if problems are found, others such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence only recommends routine imaging in those less than six months old or who have unusual findings.[28]

Differential diagnosis

In women with cervicitis (inflammation of the cervix) or vaginitis (inflammation of the vagina) and in young men with UTI symptoms, a Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection may be the cause.[10][51] These infections are typically classified as a urethritis rather than a urinary tract infection. Vaginitis may also be due to a yeast infection.[52] Interstitial cystitis (chronic pain in the bladder) may be considered for people who experience multiple episodes of UTI symptoms but urine cultures remain negative and not improved with antibiotics.[53] Prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate) may also be considered in the differential diagnosis.[54]

Hemorrhagic cystitis, characterized by blood in the urine, can occur secondary to a number of causes including: infections, radiation therapy, underlying cancer, medications and toxins.[55] Medications that commonly cause this problem include the chemotherapeutic agent cyclophosphamide with rates of 2–40%.[55] Eosinophilic cystitis is a rare condition where eosinophiles are present in the bladder wall.[56] Signs and symptoms are similar to a bladder infection.[56] Its cause is not entirely clear; however, it may be linked to food allergies, infections, and medications among others.[57]

Prevention

A number of measures have not been confirmed to affect UTI frequency including: urinating immediately after intercourse, the type of underwear used, personal hygiene methods used after urinating or defecating, or whether a person typically bathes or showers.[4] There is similarly a lack of evidence surrounding the effect of holding one's urine, tampon use, and douching.[39] In those with frequent urinary tract infections who use spermicide or a diaphragm as a method of contraception, they are advised to use alternative methods.[7] In those with benign prostatic hyperplasia urinating in a sitting position appears to improve bladder emptying[58] which might decrease urinary tract infections in this group.[citation needed]

Using urinary catheters as little and as short of time as possible and appropriate care of the catheter when used prevents catheter-associated urinary tract infections.[42] They should be inserted using sterile technique in hospital however non-sterile technique may be appropriate in those who self catheterize.[44] The urinary catheter set up should also be kept sealed.[44] Evidence does not support a significant decrease in risk when silver-alloy catheters are used.[59]

Medications

For those with recurrent infections, taking a short course of antibiotics when each infection occurs is associated with the lowest antibiotic use.[17] A prolonged course of daily antibiotics is also effective.[4] Medications frequently used include nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.[7] Some recommend against prolonged use due to concerns of antibiotic resistance.[17] Methenamine is another agent used for this purpose as in the bladder where the acidity is low it produces formaldehyde to which resistance does not develop.[60] A UK study showed that methenamine is as effective daily low-dose antibiotics at preventing UTIs among women who experience recurrent UTIs. As methenamine is an antiseptic, it may avoid the issue of antibiotic resistance.[61][62]

In cases where infections are related to intercourse, taking antibiotics afterwards may be useful.[7] In post-menopausal women, topical vaginal estrogen has been found to reduce recurrence.[63][64] As opposed to topical creams, the use of vaginal estrogen from pessaries has not been as useful as low dose antibiotics.[64] Antibiotics following short term urinary catheterization decreases the subsequent risk of a bladder infection.[65] A number of vaccines are in development as of 2018.[66][67]

Children

The evidence that preventive antibiotics decrease urinary tract infections in children is poor.[68] However recurrent UTIs are a rare cause of further kidney problems if there are no underlying abnormalities of the kidneys, resulting in less than a third of a percent (0.33%) of chronic kidney disease in adults.[69] Whether routine circumcision prevents UTIs has not been well studied as of 2011.[46]

Dietary supplements

Some research suggests that cranberry (juice or capsules) may decrease the number of UTIs in those with frequent infections.[63][70] A 2023 review concluded that cranberry products can reduce the risk of UTIs in certain groups (women with reoccurring UTIs, children, and people having had clinical interventions), but not in pregnant women, the elderly or people with urination disorders.[71] As of 2015, probiotics require further study to determine if they are beneficial.[72]

(As of 2022), one review found that taking mannose was as effective as antibiotics to prevent UTIs,[73] while another review found that clinical trial quality was too low to allow any conclusion about using D‐mannose to prevent or treat UTIs.[74]

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment is antibiotics. Phenazopyridine is occasionally prescribed during the first few days in addition to antibiotics to help with the burning and urgency sometimes felt during a bladder infection.[75] However, it is not routinely recommended due to safety concerns with its use, specifically an elevated risk of methemoglobinemia (higher than normal level of methemoglobin in the blood).[76] Paracetamol may be used for fevers.[77] There is no good evidence for the use of cranberry products for treating current infections.[78][79]

Fosfomycin can be used as an effective treatment for both UTIs and complicated UTIs including acute pyelonephritis.[80] The standard regimen for complicated UTIs is an oral 3g dose administered once every 48 or 72 hours for a total of 3 doses or a 6 grams every 8 hours for 7 days to 14 days when fosfomycin is given in IV form.[80]

Uncomplicated

Uncomplicated infections can be diagnosed and treated based on symptoms alone.[4] Antibiotics taken by mouth such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, or fosfomycin are typically first line.[81] Cephalosporins, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, or a fluoroquinolone may also be used.[82] However, antibiotic resistance to fluoroquinolones among the bacteria that cause urinary infections has been increasing.[50] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends against the use of fluoroquinolones, including a Boxed Warning, when other options are available due to higher risks of serious side effects, such as tendinitis, tendon rupture and worsening of myasthenia gravis.[83] These medications substantially shorten the time to recovery with all being equally effective.[82][84] A three-day treatment with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, or a fluoroquinolone is usually sufficient, whereas nitrofurantoin requires 5–7 days.[4][85] Fosfomycin may be used as a single dose but is not as effective.[50]

Fluoroquinolones are not recommended as a first treatment.[50][86] The Infectious Diseases Society of America states this due to the concern of generating resistance to this class of medication.[85] Amoxicillin-clavulanate appears less effective than other options.[87] Despite this precaution, some resistance has developed to all of these medications related to their widespread use.[4] Trimethoprim alone is deemed to be equivalent to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in some countries.[85] For simple UTIs, children often respond to a three-day course of antibiotics.[88] Women with recurrent simple UTIs are over 90% accurate in identifying new infections.[4] They may benefit from self-treatment upon occurrence of symptoms with medical follow-up only if the initial treatment fails.[4]

Complicated

Complicated UTIs are more difficult to treat and usually requires more aggressive evaluation, treatment, and follow-up.[89] It may require identifying and addressing the underlying complication.[90] Increasing antibiotic resistance is causing concern about the future of treating those with complicated and recurrent UTI.[91][92][93]

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Those who have bacteria in the urine but no symptoms should not generally be treated with antibiotics.[94] This includes those who are old, those with spinal cord injuries, and those who have urinary catheters.[95][96] Pregnancy is an exception and it is recommended that women take seven days of antibiotics.[97][98] If not treated it causes up to 30% of mothers to develop pyelonephritis and increases risk of low birth weight and preterm birth.[99] Some also support treatment of those with diabetes mellitus[100] and treatment before urinary tract procedures which will likely cause bleeding.[96]

Pregnant women

Urinary tract infections, even asymptomatic presence of bacteria in the urine, are more concerning in pregnancy due to the increased risk of kidney infections.[39] During pregnancy, high progesterone levels elevate the risk of decreased muscle tone of the ureters and bladder, which leads to a greater likelihood of reflux, where urine flows back up the ureters and towards the kidneys.[39] While pregnant women do not have an increased risk of asymptomatic bacteriuria, if bacteriuria is present they do have a 25–40% risk of a kidney infection.[39] Thus if urine testing shows signs of an infection—even in the absence of symptoms—treatment is recommended.[99][98] Cephalexin or nitrofurantoin are typically used because they are generally considered safe in pregnancy.[98] A kidney infection during pregnancy may result in preterm birth or pre-eclampsia (a state of high blood pressure and kidney dysfunction during pregnancy that can lead to seizures).[39] Some women have UTIs that keep coming back in pregnancy.[101] There is insufficient research on how to best treat these recurrent infections.[101]

Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis is treated more aggressively than a simple bladder infection using either a longer course of oral antibiotics or intravenous antibiotics.[3] Seven days of the oral fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin is typically used in areas where the resistance rate is less than 10%. If the local antibiotic resistance rates are greater than 10%, a dose of intravenous ceftriaxone is often prescribed.[3] Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or amoxicillin/clavulanate orally for 14 days is another reasonable option.[102] In those who exhibit more severe symptoms, admission to a hospital for ongoing antibiotics may be needed.[3] Complications such as ureteral obstruction from a kidney stone may be considered if symptoms do not improve following two or three days of treatment.[10][3]

Prognosis

With treatment, symptoms generally improve within 36 hours.[19] Up to 42% of uncomplicated infections may resolve on their own within a few days or weeks.[4][103]

15–25% of adults and children have chronic symptomatic UTIs including recurrent infections, persistent infections (infection with the same pathogen), a re-infection (new pathogen), or a relapsed infection (the same pathogen causes a new infection after it was completely gone).[74] Recurrent urinary tract infections are defined as at least two infections (episodes) in a six-month time period or three infections in twelve months, can occur in adults and in children.[74]

Cystitis refers to a urinary tract infection that involves the lower urinary tract (bladder). An upper urinary tract infection which involves the kidney is called pyelonephritis. About 10–20% of pyelonephritis will go on and develop scarring of the affected kidney. Then, 10–20% of those develop scarring will have increased risk of hypertension in later life.[104]

Epidemiology

Urinary tract infections are the most frequent bacterial infection in women.[19] They occur most frequently between the ages of 16 and 35 years, with 10% of women getting an infection yearly and more than 40–60% having an infection at some point in their lives.[7][4] Recurrences are common, with nearly half of people getting a second infection within a year. Urinary tract infections occur four times more frequently in females than males.[7] Pyelonephritis occurs between 20 and 30 times less frequently.[4] They are the most common cause of hospital-acquired infections accounting for approximately 40%.[105] Rates of asymptomatic bacteria in the urine increase with age from two to seven percent in women of child-bearing age to as high as 50% in elderly women in care homes.[39] Rates of asymptomatic bacteria in the urine among men over 75 are between 7–10%.[11] 2–10% of pregnant women have asymptomatic bacteria in the urine and higher rates are reported in women who live in some underdeveloped countries.[99]

Urinary tract infections may affect 10% of people during childhood.[7] Among children, urinary tract infections are most common in uncircumcised males less than three months of age, followed by females less than one year.[28] Estimates of frequency among children, however, vary widely. In a group of children with a fever, ranging in age between birth and two years, 2–20% were diagnosed with a UTI.[28]

History

Urinary tract infections have been described since ancient times with the first documented description in the Ebers Papyrus dated to c. 1550 BC.[20] It was described by the Egyptians as "sending forth heat from the bladder".[106] Effective treatment did not occur until the development and availability of antibiotics in the 1930s before which time herbs, bloodletting and rest were recommended.[20]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Urinary Tract Infection". 17 April 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/for-patients/common-illnesses/uti.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 13 (5): 269–284. May 2015. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3432. PMID 25853778.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "Diagnosis and treatment of acute pyelonephritis in women". American Family Physician 84 (5): 519–526. September 2011. PMID 21888302.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 "Uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adults including uncomplicated pyelonephritis". The Urologic Clinics of North America 35 (1): 1–12, v. February 2008. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.004. PMID 18061019.

- ↑ (in en) In a Page: Emergency medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2003. p. 95. ISBN 9781405103572. https://books.google.com/books?id=O0LwFPZDKbsC&pg=PA95.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Urinary Tract Infection". Statpearls. 2020. PMID 29261874.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 "Urinary tract infections in women". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 156 (2): 131–136. June 2011. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.01.028. PMID 21349630.

- ↑ "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1545–1602. October 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1459–1544. October 2016. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 10.9 "Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection and pyelonephritis". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 29 (3): 539–552. August 2011. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2011.04.001. PMID 21782073.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 "Diagnosis and management of urinary infections in older people". Clinical Medicine 11 (1): 80–83. February 2011. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.11-1-80. PMID 21404794.

- ↑ Study Guide for Pathophysiology (5 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2013. p. 272. ISBN 9780323293181. https://books.google.com/books?id=YvskCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA272.

- ↑ Introduction to Medical-Surgical Nursing. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2015. p. 909. ISBN 9781455776412. https://books.google.com/books?id=mi3uBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA909. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ Bennett & Brachman's hospital infections. (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007. p. 474. ISBN 9780781763837. https://books.google.com/books?id=tuy4zw5G4v4C&pg=PA474.

- ↑ "Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Noncatheterized Adults". The Urologic Clinics of North America 42 (4): 537–545. November 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2015.07.003. PMID 26475950.

- ↑ "Urinary Tract Infection and Bacteriuria in Pregnancy". The Urologic Clinics of North America 42 (4): 547–560. November 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2015.05.004. PMID 26475951.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Recurrent uncomplicated cystitis in women: allowing patients to self-initiate antibiotic therapy". Prescrire International 23 (146): 47–49. February 2014. PMID 24669389.

- ↑ "Factors that affect nosocomial catheter-associated urinary tract infection in intensive care units: 2-year experience at a single center". Korean Journal of Urology 54 (1): 59–65. January 2013. doi:10.4111/kju.2013.54.1.59. PMID 23362450.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 "Diagnosis and treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis". American Family Physician 84 (7): 771–776. October 2011. PMID 22010614.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 An introduction to botanical medicines : history, science, uses, and dangers. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. 2008. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-313-35009-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=HMzxKua4_rcC&pg=PA126.

- ↑ Non-vascular interventional radiology of the abdomen. New York: Springer. 2011-01-19. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4419-7731-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=au-OpXwnibMC&pg=PA67.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "Beyond Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) and Delirium: A Systematic Review of UTIs and Neuropsychiatric Disorders". Journal of Psychiatric Practice 21 (6): 402–411. November 2015. doi:10.1097/PRA.0000000000000105. PMID 26554322.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 "Associations of delirium with urinary tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults aged 65 and older: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 69 (11): 3312–3323. November 2021. doi:10.1111/jgs.17418. PMID 34448496.

- ↑ "Delirium, a Symptom of UTI in the Elderly: Fact or Fable? A Systematic Review". Canadian Geriatrics Journal 17 (1): 22–26. March 2014. doi:10.5770/cgj.17.90. PMID 24596591.

- ↑ "The scientific evidence for a potential link between confusion and urinary tract infection in the elderly is still confusing - a systematic literature review". BMC Geriatrics 19 (1): 32. February 2019. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1049-7. PMID 30717706.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Interleukin-6 mediates delirium-like phenotypes in a murine model of urinary tract infection". Journal of Neuroinflammation 18 (1): 247. October 2021. doi:10.1186/s12974-021-02304-x. PMID 34711238.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Urinary Catheterization Induces Delirium-Like Behavior Through Glucose Metabolism Impairment in Mice". Anesthesia and Analgesia 135 (3): 641–652. September 2022. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000006008. PMID 35389369.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 28.7 28.8 "Pediatric urinary tract infections". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 29 (3): 637–653. August 2011. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2011.04.004. PMID 21782079.

- ↑ "Risk of Meningitis in Infants Aged 29 to 90 Days with Urinary Tract Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Pediatrics 212: 102–110.e5. September 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.04.053. PMID 31230888.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (February 2014), "Ten Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation (AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine), http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/amda/, retrieved 20 April 2015

- ↑ "The nature of immune responses to urinary tract infections". Nature Reviews. Immunology 15 (10): 655–663. October 2015. doi:10.1038/nri3887. PMID 26388331.

- ↑ "Probiotic therapy: immunomodulating approach toward urinary tract infection". Current Microbiology 63 (5): 484–490. November 2011. doi:10.1007/s00284-011-0006-2. PMID 21901556.

- ↑ "Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 34 (1): 1–14. January 2013. doi:10.1086/668770. PMID 23221186. https://zenodo.org/record/1235706. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ↑ "Epidemiology of intensive care unit-acquired urinary tract infections". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 19 (1): 67–71. February 2006. doi:10.1097/01.qco.0000200292.37909.e0. PMID 16374221.

- ↑ "Urinary Tract Infections in Adults". http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/utiadult/.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and treatment of urethritis in men". American Family Physician 81 (7): 873–878. April 2010. PMID 20353145.

- ↑ "Recurrent urinary tract infections". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 19 (6): 861–873. December 2005. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.08.003. PMID 16298166.

- ↑ Schaechter's Mechanism of Microbial Disease. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7817-5342-5.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 39.7 39.8 "Urinary tract infections in women". The Medical Clinics of North America 95 (1): 27–41. January 2011. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.023. PMID 21095409.

- ↑ "Multidisciplinary overview of vaginal atrophy and associated genitourinary symptoms in postmenopausal women". Sexual Medicine 1 (2): 44–53. December 2013. doi:10.1002/sm2.17. PMID 25356287.

- ↑ "Common Questions About Chronic Prostatitis". American Family Physician 93 (4): 290–296. February 2016. PMID 26926816.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "The chronic indwelling catheter and urinary infection in long-term-care facility residents". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 22 (5): 316–321. May 2001. doi:10.1086/501908. PMID 11428445.

- ↑ "Short term urinary catheter policies following urogenital surgery in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD004374. April 2006. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004374.pub2. PMID 16625600.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections 2009". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 31 (4): 319–326. April 2010. doi:10.1086/651091. PMID 20156062. https://zenodo.org/record/1235702. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ↑ "Genitourinary infection and barotrauma as complications of 'P-valve' use in drysuit divers". Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine 39 (4): 210–212. December 2009. PMID 22752741. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/9482. Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Routine neonatal circumcision for the prevention of urinary tract infections in infancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11: CD009129. November 2012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009129.pub2. PMID 23152269. "The incidence of urinary tract infection (UTI) is greater in uncircumcised babies".

- ↑ "Circumcision and lifetime risk of urinary tract infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Urology 189 (6): 2118–2124. June 2013. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.114. PMID 23201382.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "Prevention of urinary tract infections in persons with spinal cord injury in home health care". Home Healthcare Nurse 28 (4): 230–241. April 2010. doi:10.1097/NHH.0b013e3181dc1bcb. PMID 20520263.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "Preoperative Antibiotics and Prevention of Sepsis in Genitourinary Surgery". Smith's Textbook of Endourology (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. 2011. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4443-4514-8.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 "Bacteruria and Urinary Tract Infections in the Elderly". The Urologic Clinics of North America 42 (4): 561–568. November 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2015.07.002. PMID 26475952.

- ↑ "Urinary infections in men". The Medical Clinics of North America 95 (1): 43–54. January 2011. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.015. PMID 21095410.

- ↑ Approach to internal medicine : a resource book for clinical practice (3rd ed.). New York: Springer. 2011-01-15. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-4419-6504-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=lnXNpj5ZzKMC&pg=PA244.

- ↑ Office urology. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press. 2000. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-89603-789-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=AdYs-QwU8KQC&pg=PA131.

- ↑ Blueprints emergency medicine (2nd ed.). Baltimore, Md.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-4051-0461-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=NvqaWHi1OTsC&pg=RA1-PA152.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Glenn's urologic surgery (7th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009. p. 148. ISBN 9780781791410. https://books.google.com/books?id=GahMzaKgMKAC&pg=PA148.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Clinical pediatric urology (4. ed.). London: Dunitz. 2002. p. 338. ISBN 9781901865639. https://books.google.com/books?id=IKexq6xCRmIC&pg=PA338.

- ↑ "The spectrum of eosinophilic cystitis in males: case series and literature review". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 133 (2): 289–294. February 2009. doi:10.5858/133.2.289. PMID 19195972.

- ↑ "Urinating standing versus sitting: position is of influence in men with prostate enlargement. A systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS ONE 9 (7): e101320. 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101320. PMID 25051345. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j1320D.

- ↑ "Types of indwelling urethral catheters for short-term catheterisation in hospitalised adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9 (9): CD004013. September 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004013.pub4. PMID 25248140.

- ↑ Pharmacology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009. pp. 397. ISBN 9780781771559. https://books.google.com/books?id=Q4hG2gRhy7oC&pg=PA397.

- ↑ "Methenamine is as good as antibiotics at preventing urinary tract infections" (in en). NIHR Evidence. 2022-12-20. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_55378. https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/alert/methenamine-as-good-as-antibiotics-preventing-urinary-tract-infections/. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ↑ "Alternative to prophylactic antibiotics for the treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: multicentre, open label, randomised, non-inferiority trial". BMJ 376: e068229. March 2022. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-0068229. PMID 35264408.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 "Non-Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Urinary Tract Infections". Pathogens 5 (2): 36. April 2016. doi:10.3390/pathogens5020036. PMID 27092529.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005131. April 2008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005131.pub2. PMID 18425910.

- ↑ "Antibiotic prophylaxis for urinary tract infections after removal of urinary catheter: meta-analysis". BMJ 346: f3147. June 2013. doi:10.1136/bmj.f3147. PMID 23757735.

- ↑ "Vaccine Development for Urinary Tract Infections: Where Do We Stand?". European Urology Focus 5 (1): 39–41. January 2019. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2018.07.034. PMID 30093359.

- ↑ "The development and early clinical testing of the ExPEC4V conjugate vaccine against uropathogenic Escherichia coli". Clinical Microbiology and Infection 24 (10): 1046–1050. October 2018. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.05.009. PMID 29803843.

- ↑ "Long-term antibiotics for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Disease in Childhood 95 (7): 499–508. July 2010. doi:10.1136/adc.2009.173112. PMID 20457696.

- ↑ "Childhood urinary tract infections as a cause of chronic kidney disease". Pediatrics 128 (5): 840–847. November 2011. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3520. PMID 21987701.

- ↑ "Cranberry-containing products for prevention of urinary tract infections in susceptible populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Archives of Internal Medicine 172 (13): 988–996. July 2012. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3004. PMID 22777630.

- ↑ "Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023 (11): CD001321. November 2023. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub7. PMID 37947276.

- ↑ "Probiotics for preventing urinary tract infections in adults and children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 (12): CD008772. December 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008772.pub2. PMID 26695595.

- ↑ "D-mannose vs other agents for recurrent urinary tract infection prevention in adult women: a systematic review and meta-analysis". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 223 (2): 265.e1–265.e13. August 2020. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.048. PMID 32497610.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 "D-mannose for preventing and treating urinary tract infections". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022 (8): CD013608. August 2022. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013608.pub2. PMID 36041061.

- ↑ "Phenazopyridine hydrochloride: the use and abuse of an old standby for UTI". Urologic Nursing 24 (3): 207–209. June 2004. PMID 15311491.

- ↑ Meyler's side effects of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. 2008. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-444-53273-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=2WxotnWiiWkC&pg=PA219.

- ↑ Family practice guidelines (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. 2010. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-8261-1812-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=4uKsZZ4BoRUC&pg=PA271.

- ↑ "Cranberry juice for the prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections". Drugs of Today 43 (1): 47–54. January 2007. doi:10.1358/dot.2007.43.1.1032055. PMID 17315052.

- ↑ "Cranberry and urinary tract infections". Drugs 69 (7): 775–807. 2009. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969070-00002. PMID 19441868.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 "Oral and Intravenous Fosfomycin for the Treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections". The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology (Hindawi Limited) 2020: 8513405. 2020-03-28. doi:10.1155/2020/8513405. PMID 32300381.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infections in the outpatient setting: a review". JAMA 312 (16): 1677–1684. 22 October 2014. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.12842. PMID 25335150.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 "Antimicrobial agents for treating uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 10 (10): CD007182. October 2010. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007182.pub2. PMID 20927755.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA updates warnings for oral and injectable fluoroquinolone antibiotics due to disabling side effects". 8 March 2018. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-updates-warnings-oral-and-injectable-fluoroquinolone-antibiotics.

- ↑ "Assessment and management of lower urinary tract infection in adults". Australian Prescriber 37 (1): 7–9. February 2014. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2014.002.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 "International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases". Clinical Infectious Diseases 52 (5): e103–e120. March 2011. doi:10.1093/cid/ciq257. PMID 21292654.

- ↑ American Urogynecologic Society (5 May 2015), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation (American Urogynecologic Society), http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-urogynecologic-society/, retrieved 1 June 2015

- ↑ "Comparative effectiveness of antibiotics for uncomplicated urinary tract infections: network meta-analysis of randomized trials". Family Practice 29 (6): 659–670. December 2012. doi:10.1093/fampra/cms029. PMID 22516128.

- ↑ "BestBets: Is a short course of antibiotics better than a long course in the treatment of UTI in children". 15 December 2006. http://www.bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=939.

- ↑ Infectious diseases in primary care. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. 2002. pp. 319. ISBN 978-0-7216-9056-8. http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/infectious%20disease/Urinary%20Tract%20Infections.htm.

- ↑ "Prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections". Minerva Urologica e Nefrologica 65 (1): 9–20. March 2013. PMID 23538307.

- ↑ "Complicated urinary tract infections: practical solutions for the treatment of multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 65 (Suppl 3): iii25–iii33. November 2010. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq298. PMID 20876625.

- ↑ "Management of urinary tract infections in the era of increasing antimicrobial resistance". The Medical Clinics of North America 97 (4): 737–57, xii. July 2013. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2013.03.006. PMID 23809723.

- ↑ "Ceftriaxone treatment of complicated urinary tract infections as a risk factor for enterococcal re-infection and prolonged hospitalization: A 6-year retrospective study". Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences 18 (4): 361–366. November 2018. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2018.3544. PMID 29750894.

- ↑ "Asymptomatic bacteriuria - prevalence in the elderly population". Australian Family Physician 40 (10): 805–809. October 2011. PMID 22003486.

- ↑ "Asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults". American Family Physician 74 (6): 985–990. September 2006. PMID 17002033.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 American Geriatrics Society, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation (American Geriatrics Society), http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-geriatrics-society/, retrieved 1 August 2013

- ↑ "Duration of treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 (11): CD000491. November 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000491.pub3. PMID 26560337.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 "Different antibiotic regimens for treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD007855. September 2010. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007855.pub2. PMID 20824868.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 "Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019 (11): CD000490. November 2019. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000490.pub4. PMID 31765489.

- ↑ "Genitourinary infection in diabetes". Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 17 (Suppl 1): S83–S87. October 2013. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.119512. PMID 24251228.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 "Interventions for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection during pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 (7): CD009279. July 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009279.pub3. PMID 26221993.

- ↑ The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy 2011 (Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy (Sanford)). Antimicrobial Therapy. 2011. pp. 30. ISBN 978-1-930808-65-2. https://archive.org/details/sanfordguidetoan00davi_0/page/30.

- ↑ "The Emergency Department Diagnosis and Management of Urinary Tract Infection". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 36 (4): 685–710. November 2018. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2018.06.003. PMID 30296999.

- ↑ "A review of renal scarring in children". Nuclear Medicine Communications 17 (3): 176–190. March 1996. doi:10.1097/00006231-199603000-00002. PMID 8692483.

- ↑ "Management of Patients with Urinary Disorders". Brunner & Suddarth's textbook of medical-surgical nursing. (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2010. p. 1359. ISBN 978-0-7817-8589-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=SmtjSD1x688C&pg=PA1359.

- ↑ Topley and Wilson's Principles of bacteriology, virology and immunity : in 4 volumes (8th ed.). London: Arnold. 1990. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7131-4591-5.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|