Chemistry:Dicobalt octacarbonyl

| |

Co2(CO)8 soaked in hexanes

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Octacarbonyldicobalt(Co—Co)

| |

| Other names

Cobalt carbonyl (2:8), di-mu-Carbonylhexacarbonyldicobalt, Cobalt octacarbonyl, Cobalt tetracarbonyl dimer, Dicobalt carbonyl, Octacarbonyldicobalt

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 3281 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Co 2(CO) 8 | |

| Molar mass | 341.95 g/mol |

| Appearance | red-orange crystals |

| Density | 1.87 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 51 to 52 °C (124 to 126 °F; 324 to 325 K) |

| Boiling point | 52 °C (126 °F; 325 K) decomposes |

| insoluble | |

| Vapor pressure | 0.7 mmHg (20 °C)[1] |

| Structure | |

| 1.33 D (C2v isomer) 0 D (D3d isomer) | |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Potential carcinogen |

| Safety data sheet | External SDS |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

| H251, H302, H304, H315, H317, H330, H351, H361, H412 | |

| P201, P260, P273, P280, P304+340+310, P403+233 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | -23 °C (-9.4 °F) [1] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

15 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

none[1] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 0.1 mg/m3[1] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

N.D.[1] |

| Related compounds | |

Related metal carbonyls

|

Iron pentacarbonyl Diiron nonacarbonyl Nickel tetracarbonyl |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

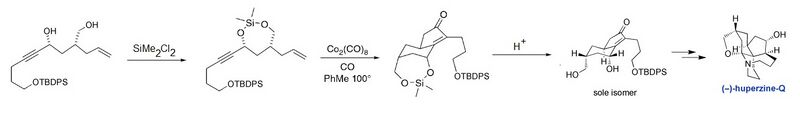

Dicobalt octacarbonyl is an organocobalt compound with composition Co

2(CO)

8. This metal carbonyl is used as a reagent and catalyst in organometallic chemistry and organic synthesis, and is central to much known organocobalt chemistry.[2][3] It is the parent member of a family of hydroformylation catalysts.[4] Each molecule consists of two cobalt atoms bound to eight carbon monoxide ligands, although multiple structural isomers are known.[5] Some of the carbonyl ligands are labile.

Synthesis, structure, properties

Dicobalt octacarbonyl an orange-colored, pyrophoric solid.[6] It is synthesised by the high pressure carbonylation of cobalt(II) salts:[6]

- 2 (CH

3COO)

2Co + 8 CO + 2 H

2 → Co

2(CO)

8 + 4 CH

3COOH

The preparation is often carried out in the presence of cyanide, converting the cobalt(II) salt into a pentacyanocobaltate(II) complex that reacts with carbon monoxide to yield K[Co(CO)

4]. Acidification produces cobalt tetracarbonyl hydride, HCo(CO)

4, which degrades near room temperature to dicobalt octacarbonyl and hydrogen.[3][7] It can also be prepared by heating cobalt metal to above 250 °C in a stream of carbon monoxide gas at about 200 to 300 atm:[3]

- 2 Co + 8 CO → Co

2(CO)

8

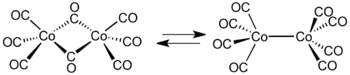

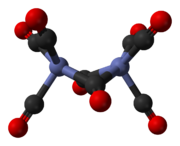

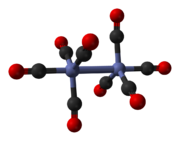

It exist as a mixture of rapidly interconverting isomers.[2][3] In solution, there are two isomers known that rapidly interconvert:[5]

The major isomer (on the left in the above equilibrium process) contains two bridging carbonyl ligands linking the cobalt centres and six terminal carbonyl ligands, three on each metal.[5] It can be summarised by the formula (CO)

3Co(μ-CO)

2Co(CO)

3 and has C2v symmetry. This structure resembles diiron nonacarbonyl (Fe

2(CO)

9) but with one fewer bridging carbonyl. The Co–Co distance is 2.52 Å, and the Co–COterminal and Co–CObridge distances are 1.80 and 1.90 Å, respectively.[8] Analysis of the bonding suggests the absence of a direct cobalt–cobalt bond.[9]

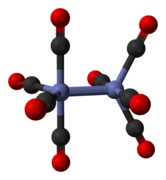

The minor isomer has no bridging carbonyl ligands, but instead has a direct bond between the cobalt centres and eight terminal carbonyl ligands, four on each metal atom.[5] It can be summarised by the formula (CO)

4Co-Co(CO)

4 and has D4d symmetry. It features an unbridged cobalt–cobalt bond that is 2.70 Å in length in the solid structure when crystallized together with C60.[10]

Reactions

Reduction

Dicobalt octacarbonyl is reductively cleaved by alkali metals and related reagents, such as sodium amalgam. The resulting salts protonate to give tetracarbonyl cobalt hydride:[3]

- Co

2(CO)

8 + 2 Na → 2 Na[Co(CO)

4] - Na[Co(CO)

4] + H+

→ H[Co(CO)

4] + Na+

Salts of this form are also intermediates in the cyanide synthesis pathway for dicobalt octacarbonyl.[7]

Reactions with electrophiles

Halogens and related reagents cleave the Co–Co bond to give pentacoordinated halotetracarbonyls:

- Co

2(CO)

8 + Br

2 → 2 Br[Co(CO)

4]

Cobalt tricarbonyl nitrosyl is produced by treatment of dicobalt octacarbonyl with nitric oxide:

- Co

2(CO)

8 + 2 NO → 2 Co(CO)

3NO + 2 CO

Reactions with alkynes

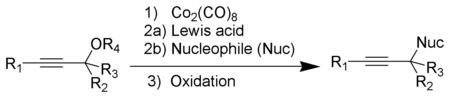

The Nicholas reaction is a substitution reaction whereby an alkoxy group located on the α-carbon of an alkyne is replaced by another nucleophile. The alkyne reacts first with dicobalt octacarbonyl, from which is generated a stabilized propargylic cation that reacts with the incoming nucleophile and the product then forms by oxidative demetallation.[11][12]

The Pauson–Khand reaction,[13] in which an alkyne, an alkene, and carbon monoxide cyclize to give a cyclopentenone, can be catalyzed by Co

2(CO)

8,[3][14] though newer methods that are more efficient have since been developed:[15][16]

Co

2(CO)

8 reacts with alkynes to form a stable covalent complex, which is useful as a protective group for the alkyne. This complex itself can also be used in the Pauson–Khand reaction.[13]

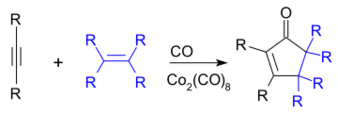

Intramolecular Pauson–Khand reactions, where the starting material contains both the alkene and alkyne moieties, are possible. In the asymmetric synthesis of the Lycopodium alkaloid huperzine-Q, Takayama and co-workers used an intramolecular Pauson–Khand reaction to cyclise an enyne containing a tert-butyldiphenylsilyl (TBDPS) protected primary alcohol.[17] The preparation of the cyclic siloxane moiety immediately prior to the introduction of the dicobalt octacarbonyl ensures that the product is formed with the desired conformation.[18]

2) to an aldehyde (RCH

2CH

2CHO):[4]

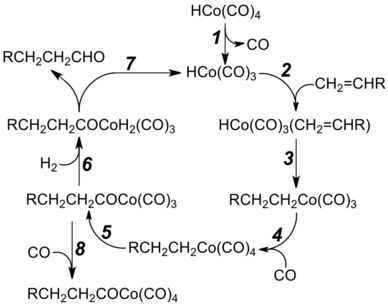

Step 1: Dissociation of carbon monoxide from cobalt tetracarbonyl hydride to form HCo(CO)

3, the active catalytic species

Step 2: The cobalt centre forms a π bond to the alkene

Step 3: Alkene ligand inserts into the cobalt–hydride bond

Step 4: Coordination of an additional carbonyl ligand

Step 5: Migratory insertion of a carbonyl ligand into the cobalt–alkyl bond, converting the alkyl tetracarbonyl intermediate into an acyl tricarbonyl species[19]

Step 6: Oxidative addition of dihydrogen leads to a dihydrido complex

Step 7: Aldehyde product released by reductive elimination,[20] regenerating the active catalytic species

Step 8: An unproductive and reversible side reaction

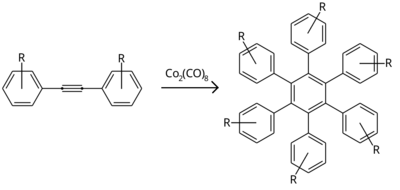

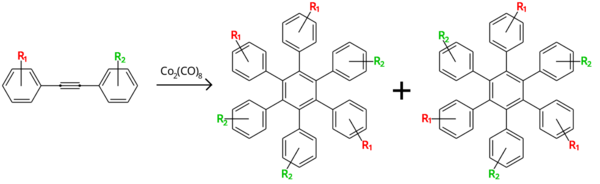

Dicobalt octacarbonyl can catalyze alkyne trimerisation of diphenylacetylene and its derivatives to hexaphenylbenzenes.[21] Symmetrical diphenylacetylenes form 6-substituted hexaphenylbenzenes, while asymmetrical diphenylacetylenes form a mixture of two isomers.[22]

Hydroformylation

Hydrogenation of Co

2(CO)

8 produces cobalt tetracarbonyl hydride H[Co(CO)

4]:[23]

- Co

2(CO)

8 + H

2 → 2 H[Co(CO)

4]

This hydride is a catalyst for hydroformylation – the conversion of alkenes to aldehydes.[4][23] The catalytic cycle for this hydroformylation is shown in the diagram.[4][19][20]

Substitution reactions

The CO ligands can be replaced with tertiary phosphine ligands to give Co

2(CO)−

8

x(PR

3)

x. These bulky derivatives are more selective catalysts for hydroformylation reactions.[3] "Hard" Lewis bases, e.g. pyridine, cause disproportionation:

- 12 C

5H

5N + 3 Co

2(CO)

8 → 2 [Co(C

5H

5N)

6][Co(CO)

4]

2 + 8 CO

3(CO)

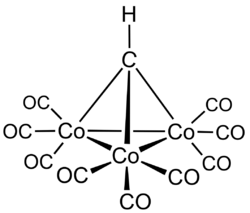

9, an organocobalt cluster compound structurally related to tetracobalt dodecacarbonyl

Conversion to higher carbonyls

Heating causes decarbonylation and formation of tetracobalt dodecacarbonyl:[3][24]

- 2 Co

2(CO)

8 → Co

4(CO)

12 + 4 CO

Like many metal carbonyls, dicobalt octacarbonyl abstracts halides from alkyl halides. Upon reaction with bromoform, it converts to methylidynetricobaltnonacarbonyl, HCCo

3(CO)

9, by a reaction that can be idealised as:[25]

- 9 Co

2(CO)

8 + 4 CHBr

3 → 4 HCCo

3(CO)

9 + 36 CO + 6 CoBr

2

Safety

Co

2(CO)

8 a volatile source of cobalt(0), is pyrophoric and releases carbon monoxide upon decomposition.[26] The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has recommended that workers should not be exposed to concentrations greater than 0.1 mg/m3 over an eight-hour time-weighted average, without the proper respiratory gear.[27]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0147". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0147.html.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Pauson, Peter L.; Stambuli, James P.; Chou, Teh-Chang; Hong, Bor-Cherng (2014). "Octacarbonyldicobalt". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1002/047084289X.ro001.pub3. ISBN 9780470842898.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Donaldson, John Dallas; Beyersmann, Detmar (2005). "Cobalt and Cobalt Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_281.pub2. ISBN 3527306730.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Elschenbroich, C.; Salzer, A. (1992). Organometallics: A Concise Introduction (2nd ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-28165-7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Sweany, Ray L.; Brown, Theodore L. (1977). "Infrared spectra of matrix-isolated dicobalt octacarbonyl. Evidence for the third isomer". Inorganic Chemistry 16 (2): 415–421. doi:10.1021/ic50168a037.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Gilmont, Paul; Blanchard, Arthur A. (1946). Dicobalt Octacarbonyl, Cobalt Nitrosyl Tricarbonyl, and Cobalt Tetracarbonyl Hydride. Inorganic Syntheses. 2. pp. 238–243. doi:10.1002/9780470132333.ch76. ISBN 9780470132333.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Orchin, Milton (1953). "Hydrogenation of Organic Compounds with Synthesis Gas". Advances in Catalysis. 5. Academic Press. pp. 385–415. ISBN 9780080565095. https://books.google.com/books?id=f_Oiij4V98cC&pg=PA409.

- ↑ Sumner, G. Gardner; Klug, Harold P.; Alexander, Leroy E. (1964). "The crystal structure of dicobalt octacarbonyl". Acta Crystallographica 17 (6): 732–742. doi:10.1107/S0365110X64001803.

- ↑ Green, Jennifer C.; Green, Malcolm L. H.; Parkin, Gerard (2012). "The occurrence and representation of three-centre two-electron bonds in covalent inorganic compounds". Chemical Communications 2012 (94): 11481–11503. doi:10.1039/c2cc35304k. PMID 23047247.

- ↑ Garcia, Thelma Y.; Fettinger, James C.; Olmstead, Marilyn M.; Balch, Alan L. (2009). "Splendid symmetry: Crystallization of an unbridged isomer of Co2(CO)8 in Co2(CO)8·C60". Chemical Communications 2009 (46): 7143–7145. doi:10.1039/b915083h. PMID 19921010.

- ↑ Nicholas, Kenneth M. (1987). "Chemistry and synthetic utility of cobalt-complexed propargyl cations". Acc. Chem. Res. 20 (6): 207–214. doi:10.1021/ar00138a001.

- ↑ Teobald, Barry J. (2002). "The Nicholas reaction: The use of dicobalt hexacarbonyl-stabilised propargylic cations in synthesis". Tetrahedron 58 (21): 4133–4170. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00315-0.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Pauson, P. L.; Khand, I. U. (1977). "Uses of Cobalt-Carbonyl Acetylene Complexes in Organic Synthesis". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 295 (1): 2–14. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb41819.x. Bibcode: 1977NYASA.295....2P.

- ↑ Blanco-Urgoiti, Jaime; Añorbe, Loreto; Pérez-Serrano, Leticia; Domínguez, Gema; Pérez-Castells, Javier (2004). "The Pauson–Khand reaction, a powerful synthetic tool for the synthesis of complex molecules". Chem. Soc. Rev. 33 (1): 32–42. doi:10.1039/b300976a. PMID 14737507.

- ↑ Schore, Neil E. (1991). "The Pauson–Khand Cycloaddition Reaction for Synthesis of Cyclopentenones". Org. React. 40: 1–90. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or040.01. ISBN 0471264180.

- ↑ Gibson, Susan E.; Stevenazzi, Andrea (2003). "The Pauson–Khand Reaction: The Catalytic Age Is Here!". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42 (16): 1800–1810. doi:10.1002/anie.200200547. PMID 12722067.

- ↑ Nakayama, Atsushi; Kogure, Noriyuki; Kitajima, Mariko; Takayama, Hiromitsu (2011). "Asymmetric Total Synthesis of a Pentacyclic Lycopodium Alkaloid: Huperzine-Q". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50 (35): 8025–8028. doi:10.1002/anie.201103550. PMID 21751323.

- ↑ Ho, Tse-Lok (2016). "Dicobalt Octacarbonyl". Fiesers' Reagents for Organic Synthesis. 28. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 251–252. ISBN 9781118942819. https://books.google.com/books?id=AO3bCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA251.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Heck, Richard F.; Breslow, David S. (1961). "The Reaction of Cobalt Hydrotetracarbonyl with Olefins". Journal of the American Chemical Society 83 (19): 4023–4027. doi:10.1021/ja01480a017.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Halpern, Jack (2001). "Organometallic chemistry at the threshold of a new millennium. Retrospect and prospect.". Pure and Applied Chemistry 73 (2): 209–220. doi:10.1351/pac200173020209.

- ↑ Vij, V.; Bhalla, V.; Kumar, M. (8 August 2016). "Hexaarylbenzene: Evolution of Properties and Applications of Multitalented Scaffold". Chemical Reviews 116 (16): 9565–9627. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00144.

- ↑ Xiao, W.; Feng, X.; Ruffieux, P.; Gröning, O.; Müllen, K.; Fasel, R. (18 June 2008). "Self-Assembly of Chiral Molecular Honeycomb Networks on Au(111)". Journal of the American Chemical Society 130 (28): 8910–8912. doi:10.1021/ja7106542.

- ↑ Jump up to: 23.0 23.1 Pfeffer, M.; Grellier, M. (2007). "Cobalt Organometallics". Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry III. 7. Elsevier. pp. 1–119. doi:10.1016/B0-08-045047-4/00096-0. ISBN 9780080450476.

- ↑ Chini, P. (1968). "The closed metal carbonyl clusters". Inorganica Chimica Acta Reviews 2: 31–51. doi:10.1016/0073-8085(68)80013-0.

- ↑ Nestle, Mara O.; Hallgren, John E.; Seyferth, Dietmar; Dawson, Peter; Robinson, Brian H. (2007). "μ3-Methylidyne and μ3-Benzylidyne-Tris(Tricarbonylcobalt)". Inorganic Syntheses. 20. 226–229. doi:10.1002/9780470132517.ch53. ISBN 9780470132517.

- ↑ Cole Parmer MSDS

- ↑ CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

|