Biology:Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

Generic protein structure example |

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), also known as DNA nucleotidylexotransferase (DNTT) or terminal transferase, is a specialized DNA polymerase expressed in immature, pre-B, pre-T lymphoid cells, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma cells. TdT adds N-nucleotides to the V, D, and J exons of the TCR and BCR genes during antibody gene recombination, enabling the phenomenon of junctional diversity. In humans, terminal transferase is encoded by the DNTT gene.[1][2] As a member of the X family of DNA polymerase enzymes, it works in conjunction with polymerase λ and polymerase μ, both of which belong to the same X family of polymerase enzymes. The diversity introduced by TdT has played an important role in the evolution of the vertebrate immune system, significantly increasing the variety of antigen receptors that a cell is equipped with to fight pathogens. Studies using TdT knockout mice have found drastic reductions (10-fold) in T-cell receptor (TCR) diversity compared with that of normal, or wild-type, systems. The greater diversity of TCRs that an organism is equipped with leads to greater resistance to infection.[3][4] Although TdT was one of the first DNA polymerases identified in mammals in 1960,[5] it remains one of the least understood of all DNA polymerases.[3] In 2016–18, TdT was discovered to demonstrate in trans template dependant behaviour in addition to its more broadly known template independent behaviour[6][7]

TdT is absent in fetal liver HSCs, significantly impairing junctional diversity in B-cells during the fetal period.[8]

Function and regulation

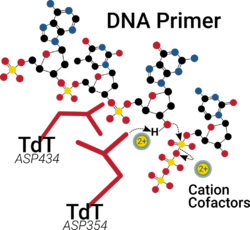

Generally, TdT catalyses the addition of nucleotides to the 3' terminus of a DNA molecule. Unlike most DNA polymerases, it does not require a template. The preferred substrate of this enzyme is a 3'-overhang, but it can also add nucleotides to blunt or recessed 3' ends. Further, TdT is the only polymerase that is known to catalyze the synthesis of 2-15nt DNA polymers from free nucleotides in solution in vivo.[9] In vitro, this behaviour catalyzes the general formation of DNA polymers without specific length.[10] The 2-15nt DNA fragments produced in vivo are hypothesized to act in signaling pathways related to DNA repair and/or recombination machinery.[9] Like many polymerases, TdT requires a divalent cation cofactor,[11] however, TdT is unique in its ability to use a broader range of cations such as Mg2+, Mn2+, Zn2+ and Co2+.[11] The rate of enzymatic activity depends on the available divalent cations and the nucleotide being added.[12]

TdT is expressed mostly in the primary lymphoid organs, like the thymus and bone marrow. Regulation of its expression occurs via multiple pathways. These include protein-protein interactions, like those with TdIF1. TdIF1 is another protein that interacts with TdT to inhibit its function by masking the DNA binding region of the TdT polymerase. The regulation of TdT expression also exists at the transcriptional level, with regulation influenced by stage-specific factors, and occurs in a developmentally restrictive manner.[3][13][14] Although expression is typically found to be in the primary lymphoid organs, recent work has suggested that stimulation via antigen can result in secondary TdT expression along with other enzymes needed for gene rearrangement outside of the thymus for T-cells.[15] Patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia greatly over-produce TdT.[12] Cell lines derived from these patients served as one of the first sources of pure TdT and lead to the discovery that differences in activity exist between human and bovine isoforms.[12]

Mechanism

Similar to many polymerases, the catalytic site of TdT has two divalent cations in its palm domain that assist in nucleotide binding, help lower the pKa of the 3'-OH group and ultimately facilitate the departure of the resultant pyrophosphate by-product.[16][17]

Isoform Variation

Several isoforms of TdT have been observed in mice, bovines, and humans. To date, two variants have been identified in mice while three have been identified in humans.[18]

The two splice variants identified in mice are named according to their respective lengths: TdTS consists of 509 amino acids while TdTL, the longer variant, consists of 529 amino acids. The differences between TdTS and TdTL occur outside regions that bind DNA and nucleotides. That the 20 amino acid difference affects enzymatic activity is controversial, with some arguing that TdTL's modifications bestow exonuclease activity while others argue that TdTL and TdTS have nearly identical in vitro activity. Additionally, TdTL reportedly can modulate the catalytic activity of TdTS in vivo through an unknown mechanism. It is suggested that this aids in the regulation of TdT's role in V(D)J recombination.[19]

Human TdT isoforms have three variants TdTL1, TdTL2, and TdTS. TdTL1 is broadly expressed in lymphoid cell lines while TdTL2 is predominantly expressed in normal small lymphocytes. Both localize in the nucleus when expressed[20] and both possess 3'->5' exonuclease activity.[21] In contrast, TdTS isoforms do not possess exonuclease activity and perform the necessary elongation during V(D)J recombination.[21] Since a similar exonuclease activity hypothesized in murine TdTL is found in human and bovine TdTL, some postulate that bovine and human TdTL isoforms regulate TdTS isoforms in a similar manner as proposed in mice.[19] Further, some hypothesize that TdTL1 may be involved in the regulation of TdTL2 and/or TdTS activity.

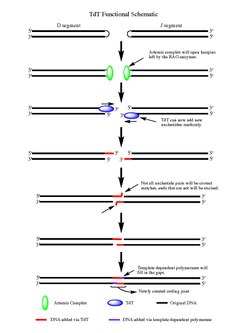

Role in V(D)J Recombination

Upon the action of the RAG 1/2 enzymes, the cleaved double-stranded DNA is left with hairpin structures at the end of each DNA segment created by the cleavage event. The hairpins are both opened by the Artemis complex, which has endonuclease activity when phosphorylated, providing the free 3' OH ends for TdT to act upon. Once the Artemis complex has done its job and added palindromic nucleotides (P-nucleotides) to the newly opened DNA hairpins, the stage is set for TdT to do its job. TdT is now able to come in and add N-nucleotides to the existing P-nucleotides in a 5' to 3' direction that polymerases are known to function. On average 2-5 random base pairs are added to each 3' end generated after the action of the Artemis complex. The number of bases added is enough for the two newly synthesized ssDNA segments to undergo microhomology alignment during non-homologous end joining according to the normal Watson-Crick base pairing patterns (A-T, C-G). From there unpaired nucleotides are excised by an exonuclease, like the Artemis Complex (which has exonuclease activity in addition to endonuclease activity), and then template-dependent polymerases can fill the gaps, finally creating the new coding joint with the action of ligase to combine the segments. Although TdT does not discriminate among the four base pairs when adding them to the N-nucleotide segments, it has shown a bias for guanine and cytosine base pairs.[3]

Template Dependent Activity

In a template-dependant manner, TdT can incorporate nucleotides across strand breaks in double-stranded DNA in a manner referred to as in trans in contrast to the in cis mechanism found in most polymerases. This occurs optimally with a one base-pair break between strands and less so with an increasing gap. This is facilitated by a subsection of TdT called Loop1 which selectively probes for short breaks in double-stranded DNA. Further, the discovery of this template dependant activity has led to more convincing mechanistic hypotheses as to how the distribution of lengths of the additions of the N regions arise in V(D)J recombination.[22]

Polymerase μ and polymerase λ exhibit similar in trans templated dependant synthetic activity to TdT, but without similar dependence on downstream double-stranded DNA.[23] Further, Polymerase λ has also been found to exhibit similar template-independent synthetic activity. Along with activity as a terminal transferase, it is known to also work in a more general template-dependent fashion.[24] The similarities between TdT and polymerase μ suggest they are closely evolutionarily related.[22]

Uses

Terminal transferase has applications in molecular biology. It can be used in RACE to add nucleotides that can then be used as a template for a primer in subsequent PCR. It can also be used to add nucleotides labeled with radioactive isotopes, for example in the TUNEL assay (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling) for the demonstration of apoptosis (which is marked, in part, by fragmented DNA). It is also used in the immunofluorescence assay for the diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia.[25]

In immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry, antibodies to TdT can be used to demonstrate the presence of immature T and B cells and pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells, which possess the antigen, while mature lymphoid cells are always TdT-negative. While TdT-positive cells are found in small numbers in healthy lymph nodes and tonsils, the malignant cells of acute lymphoblastic leukemia are also TdT-positive, and the antibody can, therefore, be used as part of a panel to diagnose this disease and to distinguish it from, for example, small cell tumors of childhood.[26]

TdT has also seen recent application in the De Novo synthesis of oligonucleotides, with TdT-dNTP tethered analogs capable of primer extension by 1 nt at a time.[27] In other words, the enzyme TdT has demonstrated the capability of making synthetic DNA by adding one letter at a time to a primer sequence.

See also

References

- ↑ "Chromosome localization of the gene for human terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase to region 10q23-q25". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 82 (17): 5836–40. September 1985. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.17.5836. PMID 3862101. Bibcode: 1985PNAS...82.5836I.

- ↑ "The terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase gene is located on human chromosome 10 (10q23----q24) and on mouse chromosome 19". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics 43 (3–4): 121–6. 1986. doi:10.1159/000132309. PMID 3467897.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: the story of a misguided DNA polymerase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 1804 (5): 1151–66. May 2010. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.06.030. PMID 19596089.

- ↑ "Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase establishes and broadens antiviral CD8+ T cell immunodominance hierarchies". Journal of Immunology 181 (1): 649–59. July 2008. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.649. PMID 18566432.

- ↑ "Calf thymus polymerase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 235 (8): 2399–403. August 1960. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64634-4. PMID 13802334.

- ↑ "Structural basis for a novel mechanism of DNA bridging and alignment in eukaryotic DSB DNA repair". The EMBO Journal 34 (8): 1126–42. April 2015. doi:10.15252/embj.201489643. PMID 25762590.

- ↑ "Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase: the story of an untemplated DNA polymerase capable of DNA bridging and templated synthesis across strands". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 53: 22–31. December 2018. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2018.03.019. PMID 29656238. https://hal-pasteur.archives-ouvertes.fr/pasteur-03414957/file/TDT_COSB_final.pdf.

- ↑ Hardy, Richard (2008). "Chapter 7: B Lymphocyte Development and Biology". in Paul, William. Fundamental Immunology (Book) (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 237–269. ISBN 978-0-7817-6519-0.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "De novo DNA synthesis by human DNA polymerase lambda, DNA polymerase mu and terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase". Journal of Molecular Biology 339 (2): 395–404. May 2004. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.056. PMID 15136041.

- ↑ "[8] Nucleotide polymerizing enzymes from calf thymus gland". Nucleotide polymerizing enzymes from calf thymus gland. Methods in Enzymology. 29. 1974. pp. 70–81. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(74)29010-4. ISBN 9780121818920.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Doxynucleotide-polymerizing enzymes of calf thymus gland. IV. Inhibition of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase by metal ligands". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 65 (4): 1041–8. April 1970. doi:10.1073/pnas.65.4.1041. PMID 4985880. Bibcode: 1970PNAS...65.1041C.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Biochemical properties of purified human terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 255 (9): 4206–12. May 1980. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)85653-3. PMID 7372675.

- ↑ "Identification of a new cis-regulatory element of the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase gene in the 5' region of the murine locus". Molecular Immunology 45 (4): 1009–17. February 2008. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2007.07.027. PMID 17854898.

- ↑ "Identification of functional domains in TdIF1 and its inhibitory mechanism for TdT activity". Genes to Cells 12 (8): 941–59. August 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01105.x. PMID 17663723.

- ↑ "Antigenic stimulation induces recombination activating gene 1 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase expression in a murine T-cell hybridoma". Cellular Immunology 274 (1–2): 19–25. 2012-01-01. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.02.008. PMID 22464913.

- ↑ "Different Divalent Cations Alter the Kinetics and Fidelity of DNA Polymerases". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 291 (40): 20869–20875. September 2016. doi:10.1074/jbc.R116.742494. PMID 27462081.

- ↑ "Crystal structures of a template-independent DNA polymerase: murine terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase". The EMBO Journal 21 (3): 427–39. February 2002. doi:10.1093/emboj/21.3.427. PMID 11823435.

- ↑ "Abnormalities in the sodium transport as the causative factor for enhanced norepinephrine overflow in the spontaneously hypertensive rat". Clinical & Experimental Hypertension, Part A 10 (5): 833–41. 1988. doi:10.1080/07300077.1988.11878788. PMID 2846215.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Digitoxin metabolism by rat liver microsomes". Biochemical Pharmacology 24 (17): 1639–41. September 1975. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(75)90094-5. PMID 10. https://serval.unil.ch/notice/serval:BIB_EE7D4CC5FB04.

- ↑ "Distinct and opposite activities of human terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase splice variants". Journal of Immunology 173 (6): 4009–19. September 2004. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4009. PMID 15356150.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Isoforms of Terminal Deoxynucleotidyltransferase: Developmental Aspects and Function. Advances in Immunology. 86. 2005. pp. 113–36. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(04)86003-6. ISBN 9780120044863.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Rapid infusion of sodium bicarbonate and albumin into high-risk premature infants soon after birth: a controlled, prospective trial". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 124 (3): 263–7. February 1976. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(76)90154-x. PMID 2013.

- ↑ "Decision-making during NHEJ: a network of interactions in human Polμ implicated in substrate recognition and end-bridging". Nucleic Acids Research 42 (12): 7923–34. July 2014. doi:10.1093/nar/gku475. PMID 24878922.

- ↑ "DNA elongation by the human DNA polymerase lambda polymerase and terminal transferase activities are differentially coordinated by proliferating cell nuclear antigen and replication protein A". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (3): 1971–81. January 2005. doi:10.1074/jbc.M411650200. PMID 15537631.

- ↑ "Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 124 (1): 92–7. January 2000. doi:10.5858/2000-124-0092-TDTNAL. PMID 10629138.

- ↑ Leong, Anthony S-Y; Cooper, Kumarason; Leong, F Joel W-M (2003). Manual of Diagnostic Cytology (2nd ed.). Greenwich Medical Media, Ltd.. pp. 413–414. ISBN 1-84110-100-1.

- ↑ "De novo DNA synthesis using polymerase-nucleotide conjugates". Nature Biotechnology 36 (7): 645–650. August 2018. doi:10.1038/nbt.4173. PMID 29912208. https://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/9d4221mc.

Further reading

- "Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-positive cells in spleen, appendix and branchial cleft cysts in pediatric patients". Haematologica 91 (8): 1139–40. August 2006. PMID 16885057.

- "Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase directly interacts with a novel nuclear protein that is homologous to p65". Genes to Cells 6 (7): 641–52. July 2001. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00449.x. PMID 11473582.

- "Molecular biology of terminal transferase". CRC Critical Reviews in Biochemistry 21 (1): 27–52. 1986. doi:10.3109/10409238609113608. PMID 3524991.

- "Bood POZ containing gene type 2 is a human counterpart of yeast Btb3p and promotes the degradation of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase". Genes to Cells 13 (5): 439–57. May 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01179.x. PMID 18429817.

- "Evidence against T-cell development in the adult human intestinal mucosa based upon lack of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase expression". Immunology 87 (3): 402–7. March 1996. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.496571.x. PMID 8778025.

- "A scan of chromosome 10 identifies a novel locus showing strong association with late-onset Alzheimer disease". American Journal of Human Genetics 78 (1): 78–88. January 2006. doi:10.1086/498851. PMID 16385451.

- "Four-color flow cytometric investigation of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-positive lymphoid precursors in pediatric bone marrow: CD79a expression precedes CD19 in early B-cell ontogeny". Blood 92 (9): 3203–9. November 1998. doi:10.1182/blood.V92.9.3203. PMID 9787156.

- "Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase forms a ternary complex with a novel chromatin remodeling protein with 82 kDa and core histone". Genes to Cells 8 (6): 559–71. June 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00656.x. PMID 12786946.

- "Identification of functional domains in TdIF1 and its inhibitory mechanism for TdT activity". Genes to Cells 12 (8): 941–59. August 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01105.x. PMID 17663723.

- "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene 200 (1–2): 149–56. October 1997. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

- "Frequent N addition and clonal relatedness among immunoglobulin lambda light chains expressed in rheumatoid arthritis synovia and PBL, and the influence of V lambda gene segment utilization on CDR3 length". Molecular Medicine 4 (8): 525–53. August 1998. doi:10.1007/BF03401757. PMID 9742508.

- "Nonpositive terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase in pediatric precursor B-lymphoblastic leukemia". American Journal of Clinical Pathology 121 (6): 810–5. June 2004. doi:10.1309/QD18-PPV1-NH3T-EUTF. PMID 15198352.

- "Mutational analysis of residues in the nucleotide binding domain of human terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 269 (16): 11859–68. April 1994. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)32652-2. PMID 8163485.

- "Distinct and opposite activities of human terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase splice variants". Journal of Immunology 173 (6): 4009–19. September 2004. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4009. PMID 15356150.

- "[Expression and function of terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase and discovery of novel DNA polymerase mu]". Seikagaku. The Journal of Japanese Biochemical Society 74 (3): 227–32. March 2002. PMID 11974916.

- "Role of human Pso4 in mammalian DNA repair and association with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 (19): 10746–51. September 2003. doi:10.1073/pnas.1631060100. PMID 12960389. Bibcode: 2003PNAS..10010746M.

- "Association of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase with Ku". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (24): 13926–31. November 1999. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.24.13926. PMID 10570175. Bibcode: 1999PNAS...9613926M.

- "Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase is negatively regulated by direct interaction with proliferating cell nuclear antigen". Genes to Cells 6 (9): 815–24. September 2001. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00460.x. PMID 11554927.

External links

- Terminal+Deoxyribonucleotidyltransferase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

|