Biology:Pantothenate kinase

| Pantothenate kinase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 2.7.1.33 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 9026-48-6 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Pantothenate kinase (EC 2.7.1.33, PanK; CoaA) is the first enzyme in the Coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthetic pathway. It phosphorylates pantothenate (vitamin B5) to form 4'-phosphopantothenate at the expense of a molecule of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). It is the rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of CoA.[1][2]

CoA is a necessary cofactor in all living organisms. It acts as the major acyl group carrier in many important cellular processes, such as the citric acid cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle) and fatty acid metabolism. Consequently, pantothenate kinase is a key regulatory enzyme in the CoA biosynthetic pathway.[3]

Types

Three distinct types of PanK has been identified - PanK-I (found in bacteria), PanK-II (mainly found in eukaryotes, but also in the Staphylococci) and PanK-III, also known as CoaX (found in bacteria). Eukaryotic PanK-II enzymes often occur as different isoforms, such as PanK1, PanK2, PanK3 and PanK4. In humans, multiple PanK isoforms are expressed by four genes. PANK1 gene encodes the PanK1α and PanK1β forms, and PANK2 and PANK3 encode PanK2 and PanK3, respectively.[4] The four major isoforms found in mammals have different subcellular localizations. PanK1α is nuclear, while PanK1β and PanK3 are cytosolic. In mice, PanK2 is also cytosolic, while in humans, this enzyme is mitochondrial and nuclear.[5] The tissue distribution of these isoforms also varies. In mouse models, PanK1 is the predominant species in the heart, liver and brown adipose tissue, along with the kidneys. PanK2 and PanK3 are more prominent in the brain and skeletal muscle, and PanK3 is particularly high in the intestines and white adipose tissue.[6]

Structure

PanK-II

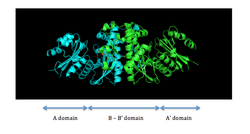

PanK-II contains two protein domains, as illustrated in Figure 1. The A domain and A' domain each has a glycine-rich loop (sequence GXXXXGKS; P loop) that is characteristic of nucleotide-binding sites; this is where ATP is assumed to bind.[7] located between residues 95 and 102 on the A domain

The two ATP binding sites display cooperative behavior. The dimerization interface consists of two long helices, one from each monomer, that interact with each other. The C-terminal ends of the helices are held together by van der Waals interactions between valine and methionine residues of each monomer. The middle of the helices is attached by hydrogen bonds between asparagine residues. At the N-terminal end, each helix widens and forms a four-helix bundle with two shorter helices. This bundle consists of a hydrophobic core formed by non-polar residues that utilize van der Waals forces to further stabilize the dimer.[4]

In the active site, pantothenate is oriented by hydrogen bonds between pantothenate and the side chains of aspartate, tyrosine, histidine, tyrosine, and asparagine residues.[8] Asparagine, histidine, and arginine residues are involved in catalysis.

Human PanK-II isoforms PanK1α, PanK1β, PanK2, and PanK3 have a common, highly homologous catalytic core of approximately 355 residues.[4] PanK1α and PanK1β are both encoded by the PANK1 gene and have the same catalytic domain of 363 amino acids, encoded by exons 2 through 7. The PanK1α transcript starts with exon 1α that encodes a 184-residue regulatory domain at the N-terminus. This region allows for feedback inhibition by free CoA and acyl-CoA and regulation by acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA. On the other hand, the PanK1β transcript starts with exon 1β, which produces a 10-residue N-terminus that does not include a feedback regulatory domain.[9]

PanK-III

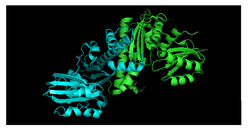

PanK-III also contains two protein domains, and the key catalytic residues of PanK-II are conserved. The monomer units of PanK-II and PanK-III are virtually identical, but they have distinctly different dimer assemblies. A study between the structures of Staphylococcus aureus type II and the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III demonstrate that the PanK-II monomer has a loop region that is absent from the PanK-III monomer, and the PanK-III monomer has a loop region that is absent from the PanK-II monomer.[10] This minor variation has a crucial difference on the dimerization interface in which the helices of the PanK-II dimer coil around one another and the helices of the PanK-III dimer interact at a 70° angle (Figure 2).[11]

As a result of this difference in dimerization interface between PanK-II and PanK-III, the conformations of the substrate binding sites for ATP and pantothenate are also distinct.[12][13]

Catalytic Mechanism

PanK-II

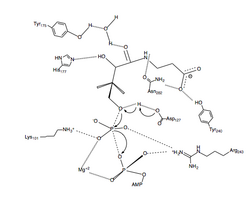

A proposed mechanism of the phosphoryl transfer reaction of PanK-II is a concerted mechanism with a dissociative transition state.

First, the ATP binds at the binding groove created by residues of the P loop and nearby residues. Here, the conserved lysine (Lys-101) is the key residue required for ATP binding.[14][15] Additionally, the side chains of residues Lys-101, Ser-102, Glu-199, and Arg-243 orient the nucleotide in the binding groove. The pantothenate is bound and oriented by forming hydrogen bond interactions with residues Asp-127, Tyr-240, Asn-282, Tyr-175, and His-177.[8] When both ATP and pantothenate are bound, Asp-127 deprotonates the C1 hydroxyl group of pantothenate. The oxygen from the pantothenate then attacks the γ-phosphate of the bound ATP. Here, charge stabilization of β- and γ-phosphate groups is achieved by Arg-243, Lys-101, and a coordinated Mg2+ ion.[16] In this concerted mechanism, the planar phosphorane of the γ-phosphate is transferred in-line to the attacking oxygen of pantothenate.[8] Finally, 4'-phosphopantothenate dissociates from PanK, followed by ADP.

Regulation of pantothenate kinase

PanK-II

The regulation of pantothenate kinase is essential to controlling the intracellular CoA concentration.[17] Pantothenate kinase is regulated via feedback inhibition by CoA and its thioesters (i.e., acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA).[18] Inhibition of the human isoforms of PanK by acetyl-CoA varies dramatically. PanK1β is inhibited the least strongly, with an IC50 value of around 5 μM, while PanK2 is the most strongly inhibited, with an IC50 of around 0.1 μM.[6]

CoA inhibits PanK activity by competitively binding to the ATP binding site and preventing ATP binding to Lys-101.[14][15] Although CoA binds at the same site as ATP, they bind in distinct orientations, and their adenine moieties interact with the enzyme with nonoverlapping sets of residues. His-177, Phe-247, and Arg-106 are necessary for CoA recognition but not for ATP, and while Asn-43 and His-307 interact with the adenine base of ATP, His-177 and Phe-247 interact with the adenine base of CoA.[16] Both molecules use Lys-101 to neutralize the charge on their respective phosphodiesters.

Nonesterified CoA has more potent inhibition than its thioesters. This phenomenon is best explained by the tight fit of the thiol group with the surrounding aromatic residues, Phe-244, Phe-259, Tyr-262, and Phe-252. Free CoA has an optimal fit, but when an acyl group is attached to CoA, the steric hindrance makes it difficult for the thioester to interact with Phe-252. Thus, the inhibition by thioesters is less effective than that by nonesterified CoA.[16]

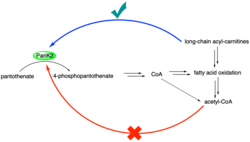

Deletion of PanK1 disrupts metabolic pathways, including fatty acid oxidation and gluconeogenesis. PanK1-/- mouse models in a fasted state show impaired gluconeogenesis, indicating that this pathway is disrupted. In addition, CoA levels decrease significantly between PanK1-/- and wild-type mice. This reduction in CoA also appears to correlate with a disruption in fatty acid oxidation. Higher levels of long-chain acyl-carnitines were observed in PanK1-/- mice, indicating a lower capability for fatty acid oxidation in these mice.[19]

Because PanK2 is so strongly inhibited by acetyl-CoA, an abundant metabolite in the mitochondria, this enzyme likely would not be active under physiological conditions without activators.[6] Palmitoyl-carnitine and other long-chain acyl-carnitines can reverse acetyl-CoA inhibition and can activate PanK2 without acetyl-CoA present. Palmitoyl-carnitine is competitive with acetyl-CoA.[20] The activation of PanK2 by palmitoyl-carnitine and other long-chain acyl-carnitines sheds light on the regulatory pathways of this enzyme: Under normal conditions, PanK2 is likely inhibited by high levels of acetyl-CoA. Without CoA production, fatty acid oxidation decreases, leading to an increase in long-chain acyl-carnitines.[19] These acyl-carnitines can then reduce inhibition by acetyl-CoA, activating PanK2 and increasing CoA biosynthesis. PanK3 is also activated by palmitoyl-carnitine and other long-chain acyl-carnitines, including oleoyl-carnitine.[21]

PanK-III

The regulation outlined above corresponds to PanK-II. PanK-III is resistant to feedback inhibition.[10][12][13]

Genes

In humans:

The PANK2 gene encodes for PanK2, which regulates the formation of CoA in mitochondria, the cell’s energy-producing centers.[22] PANK2 mutation is the cause of Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN), formerly called Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome. This rare disease presents with profound dystonia, spasticity and is often fatal.

There are many mutations in PanK2 that lead to PKAN. In a survey of several common mutations, it was found that several of these mutations did not cause a major loss in the catalytic activity of PanK2, indicating that loss of catalytic function of this enzyme is not fully responsible for this disease.[23]

References

- ↑ "Rate-limiting step and control of coenzyme A synthesis in cardiac muscle". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 257 (18): 10967–72. September 1982. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)33918-8. PMID 7107640.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Crystal structure of a type III pantothenate kinase: insight into the mechanism of an essential coenzyme A biosynthetic enzyme universally distributed in bacteria". Journal of Bacteriology 188 (15): 5532–40. August 2006. doi:10.1128/JB.00469-06. PMID 16855243.

- ↑ "Coenzyme A: back in action". Progress in Lipid Research 44 (2–3): 125–53. 2005-03-01. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2005.04.001. PMID 15893380.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Crystal structures of human pantothenate kinases. Insights into allosteric regulation and mutations linked to a neurodegeneration disorder". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (38): 27984–93. September 2007. doi:10.1074/jbc.M701915200. PMID 17631502.

- ↑ Alfonso-Pecchio, Adolfo; Garcia, Matthew; Leonardi, Roberta; Jackowski, Suzanne (2012). "Compartmentalization of mammalian pantothenate kinases". PLOS ONE 7 (11): e49509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049509. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 23152917.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Dansie, Lorraine E.; Reeves, Stacy; Miller, Karen; Zano, Stephen P.; Frank, Matthew; Pate, Caroline; Wang, Jina; Jackowski, Suzanne (August 2014). "Physiological roles of the pantothenate kinases". Biochemical Society Transactions 42 (4): 1033–1036. doi:10.1042/BST20140096. ISSN 1470-8752. PMID 25109998.

- ↑ "The P-loop--a common motif in ATP- and GTP-binding proteins". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 15 (11): 430–4. November 1990. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(90)90281-F. PMID 2126155.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "The structure of the pantothenate kinase.ADP.pantothenate ternary complex reveals the relationship between the binding sites for substrate, allosteric regulator, and antimetabolites". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (34): 35622–9. August 2004. doi:10.1074/jbc.M403152200. PMID 15136582.

- ↑ "The murine pantothenate kinase (Pank1) gene encodes two differentially regulated pantothenate kinase isozymes". Gene 291 (1–2): 35–43. 2002. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00564-4. PMID 12095677.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Structural basis for substrate binding and the catalytic mechanism of type III pantothenate kinase". Biochemistry 47 (5): 1369–80. February 2008. doi:10.1021/bi7018578. PMID 18186650.

- ↑ "Prokaryotic type II and type III pantothenate kinases: The same monomer fold creates dimers with distinct catalytic properties" (in English). Structure 14 (8): 1251–61. August 2006. doi:10.1016/j.str.2006.06.008. PMID 16905099.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Characterization of a new pantothenate kinase isoform from Helicobacter pylori". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 (21): 20185–8. May 2005. doi:10.1074/jbc.C500044200. PMID 15795230.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Inhibitors of pantothenate kinase: novel antibiotics for staphylococcal infections". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 47 (6): 2051–5. June 2003. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.6.2051-2055.2003. PMID 12760898.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Kinetics and regulation of pantothenate kinase from Escherichia coli". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 269 (43): 27051–8. October 1994. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)47124-4. PMID 7929447.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the pantothenate kinase (coaA) gene of Escherichia coli". Journal of Bacteriology 174 (20): 6411–7. October 1992. doi:10.1128/jb.174.20.6411-6417.1992. PMID 1328157.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Structural basis for the feedback regulation of Escherichia coli pantothenate kinase by coenzyme A". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (36): 28093–9. September 2000. doi:10.1074/jbc.M003190200. PMID 10862768. http://www.jbc.org/content/275/36/28093.

- ↑ "Regulation of coenzyme A biosynthesis". Journal of Bacteriology 148 (3): 926–32. December 1981. doi:10.1128/jb.148.3.926-932.1981. PMID 6796563.

- ↑ "Role of feedback regulation of pantothenate kinase (CoaA) in control of coenzyme A levels in Escherichia coli". Journal of Bacteriology 185 (11): 3410–5. June 2003. doi:10.1128/JB.185.11.3410-3415.2003. PMID 12754240.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Leonardi, Roberta; Rehg, Jerold E.; Rock, Charles O.; Jackowski, Suzanne (2010-06-14). "Pantothenate kinase 1 is required to support the metabolic transition from the fed to the fasted state". PLOS ONE 5 (6): e11107. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011107. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 20559429. Bibcode: 2010PLoSO...511107L.

- ↑ Leonardi, Roberta; Rock, Charles O.; Jackowski, Suzanne; Zhang, Yong-Mei (2007-01-30). "Activation of human mitochondrial pantothenate kinase 2 by palmitoylcarnitine" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104 (5): 1494–1499. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607621104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 17242360.

- ↑ Leonardi, Roberta; Zhang, Yong-Mei; Yun, Mi-Kyung; Zhou, Ruobing; Zeng, Fu-Yue; Lin, Wenwei; Cui, Jimmy; Chen, Taosheng et al. (2010-08-27). "Modulation of Pantothenate Kinase 3 Activity by Small Molecules that Interact with the Substrate/Allosteric Regulatory Domain" (in en). Chemistry & Biology 17 (8): 892–902. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.06.006. ISSN 1074-5521. PMID 20797618.

- ↑ "PANK2 gene". 2016-02-22. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/PANK2.

- ↑ Zhang, Yong-Mei; Rock, Charles O.; Jackowski, Suzanne (2006-01-06). "Biochemical properties of human pantothenate kinase 2 isoforms and mutations linked to pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 281 (1): 107–114. doi:10.1074/jbc.M508825200. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 16272150.

External links

- Pantothenate+kinase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- EC 2.7.1.33

|

![[2]](/wiki/images/3/34/Mechanism_os_pantothenate_kinase.png)