Information security

Information security, sometimes shortened to InfoSec,[1] is the practice of protecting information by mitigating information risks. It is part of information risk management.[2][3] It typically involves preventing or reducing the probability of unauthorized or inappropriate access to data or the unlawful use, disclosure, disruption, deletion, corruption, modification, inspection, recording, or devaluation of information.[citation needed] It also involves actions intended to reduce the adverse impacts of such incidents. Protected information may take any form, e.g., electronic or physical, tangible (e.g., paperwork), or intangible (e.g., knowledge).[4][5] Information security's primary focus is the balanced protection of data confidentiality, integrity, and availability (also known as the "CIA" triad) while maintaining a focus on efficient policy implementation, all without hampering organization productivity.[6] This is largely achieved through a structured risk management process that involves:

- Identifying information and related assets, plus potential threats, vulnerabilities, and impacts;

- Evaluating the risks

- Deciding how to address or treat the risks, i.e., to avoid, mitigate, share, or accept them

- Where risk mitigation is required, selecting or designing appropriate security controls and implementing them

- Monitoring the activities and making adjustments as necessary to address any issues, changes, or improvement opportunities[7]

To standardize this discipline, academics and professionals collaborate to offer guidance, policies, and industry standards on passwords, antivirus software, firewalls, encryption software, legal liability, security awareness and training, and so forth.[8] This standardization may be further driven by a wide variety of laws and regulations that affect how data is accessed, processed, stored, transferred, and destroyed.[9] However, the implementation of any standards and guidance within an entity may have limited effect if a culture of continual improvement is not adopted.[10]

Definition

Various definitions of information security are suggested below, summarized from different sources:

- "Preservation of confidentiality, integrity and availability of information. Note: In addition, other properties, such as authenticity, accountability, non-repudiation and reliability can also be involved." (ISO/IEC 27000:2018)[12]

- "The protection of information and information systems from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction in order to provide confidentiality, integrity, and availability." (CNSS, 2010)[13]

- "Ensures that only authorized users (confidentiality) have access to accurate and complete information (integrity) when required (availability)." (ISACA, 2008)[14]

- "Information Security is the process of protecting the intellectual property of an organisation." (Pipkin, 2000)[15]

- "...information security is a risk management discipline, whose job is to manage the cost of information risk to the business." (McDermott and Geer, 2001)[16]

- "A well-informed sense of assurance that information risks and controls are in balance." (Anderson, J., 2003)[17]

- "Information security is the protection of information and minimizes the risk of exposing information to unauthorized parties." (Venter and Eloff, 2003)[18]

- "Information Security is a multidisciplinary area of study and professional activity which is concerned with the development and implementation of security mechanisms of all available types (technical, organizational, human-oriented and legal) in order to keep information in all its locations (within and outside the organization's perimeter) and, consequently, information systems, where information is created, processed, stored, transmitted and destroyed, free from threats.[19] Threats to information and information systems may be categorized and a corresponding security goal may be defined for each category of threats.[20] A set of security goals, identified as a result of a threat analysis, should be revised periodically to ensure its adequacy and conformance with the evolving environment.[21] The currently relevant set of security goals may include: confidentiality, integrity, availability, privacy, authenticity & trustworthiness, non-repudiation, accountability and auditability." (Cherdantseva and Hilton, 2013)[11]

- Information and information resource security using telecommunication system or devices means protecting information, information systems or books from unauthorized access, damage, theft, or destruction (Kurose and Ross, 2010).[22]

Overview

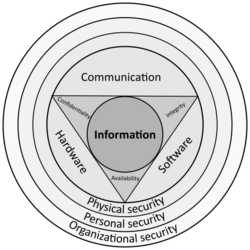

At the core of information security is information assurance, the act of maintaining the confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) of information, ensuring that information is not compromised in any way when critical issues arise.[23] These issues include but are not limited to natural disasters, computer/server malfunction, and physical theft. While paper-based business operations are still prevalent, requiring their own set of information security practices, enterprise digital initiatives are increasingly being emphasized,[24][25] with information assurance now typically being dealt with by information technology (IT) security specialists. These specialists apply information security to technology (most often some form of computer system). It is worthwhile to note that a computer does not necessarily mean a home desktop.[26] A computer is any device with a processor and some memory. Such devices can range from non-networked standalone devices as simple as calculators, to networked mobile computing devices such as smartphones and tablet computers.[27] IT security specialists are almost always found in any major enterprise/establishment due to the nature and value of the data within larger businesses.[28] They are responsible for keeping all of the technology within the company secure from malicious cyber attacks that often attempt to acquire critical private information or gain control of the internal systems.[29][30]

The field of information security has grown and evolved significantly in recent years.[31] It offers many areas for specialization, including securing networks and allied infrastructure, securing applications and databases, security testing, information systems auditing, business continuity planning, electronic record discovery, and digital forensics.[citation needed] Information security professionals are very stable in their employment.[32] (As of 2013) more than 80 percent of professionals had no change in employer or employment over a period of a year, and the number of professionals is projected to continuously grow more than 11 percent annually from 2014 to 2019.[33]

Threats

Information security threats come in many different forms.[34][35] Some of the most common threats today are software attacks, theft of intellectual property, theft of identity, theft of equipment or information, sabotage, and information extortion.[36][37] Viruses,[38] worms, phishing attacks, and Trojan horses are a few common examples of software attacks. The theft of intellectual property has also been an extensive issue for many businesses in the information technology (IT) field.[39] Identity theft is the attempt to act as someone else usually to obtain that person's personal information or to take advantage of their access to vital information through social engineering.[40][41] Theft of equipment or information is becoming more prevalent today due to the fact that most devices today are mobile,[42] are prone to theft and have also become far more desirable as the amount of data capacity increases. Sabotage usually consists of the destruction of an organization's website in an attempt to cause loss of confidence on the part of its customers.[43] Information extortion consists of theft of a company's property or information as an attempt to receive a payment in exchange for returning the information or property back to its owner, as with ransomware.[44] There are many ways to help protect yourself from some of these attacks but one of the most functional precautions is conduct periodical user awareness.[45] The number one threat to any organisation are users or internal employees, they are also called insider threats.[46]

Governments, military, corporations, financial institutions, hospitals, non-profit organisations, and private businesses amass a great deal of confidential information about their employees, customers, products, research, and financial status.[47] Should confidential information about a business's customers or finances or new product line fall into the hands of a competitor or a black hat hacker, a business and its customers could suffer widespread, irreparable financial loss, as well as damage to the company's reputation.[48] From a business perspective, information security must be balanced against cost; the Gordon-Loeb Model provides a mathematical economic approach for addressing this concern.[49]

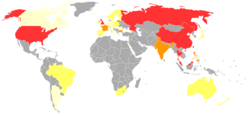

For the individual, information security has a significant effect on privacy, which is viewed very differently in various cultures.[50]

Responses to threats

Possible responses to a security threat or risk are:[51]

- reduce/mitigate – implement safeguards and countermeasures to eliminate vulnerabilities or block threats

- assign/transfer – place the cost of the threat onto another entity or organization such as purchasing insurance or outsourcing

- accept – evaluate if the cost of the countermeasure outweighs the possible cost of loss due to the threat[52]

History

Since the early days of communication, diplomats and military commanders understood that it was necessary to provide some mechanism to protect the confidentiality of correspondence and to have some means of detecting tampering.[citation needed] Julius Caesar is credited with the invention of the Caesar cipher c. 50 B.C., which was created in order to prevent his secret messages from being read should a message fall into the wrong hands.[53] However, for the most part protection was achieved through the application of procedural handling controls.[54][55] Sensitive information was marked up to indicate that it should be protected and transported by trusted persons, guarded and stored in a secure environment or strong box.[56] As postal services expanded, governments created official organizations to intercept, decipher, read, and reseal letters (e.g., the U.K.'s Secret Office, founded in 1653[57]).

In the mid-nineteenth century more complex classification systems were developed to allow governments to manage their information according to the degree of sensitivity.[58] For example, the British Government codified this, to some extent, with the publication of the Official Secrets Act in 1889.[59] Section 1 of the law concerned espionage and unlawful disclosures of information, while Section 2 dealt with breaches of official trust.[60] A public interest defense was soon added to defend disclosures in the interest of the state.[61] A similar law was passed in India in 1889, The Indian Official Secrets Act, which was associated with the British colonial era and used to crack down on newspapers that opposed the Raj's policies.[62] A newer version was passed in 1923 that extended to all matters of confidential or secret information for governance.[63] By the time of the First World War, multi-tier classification systems were used to communicate information to and from various fronts, which encouraged greater use of code making and breaking sections in diplomatic and military headquarters.[64] Encoding became more sophisticated between the wars as machines were employed to scramble and unscramble information.[65]

The establishment of computer security inaugurated the history of information security. The need for such appeared during World War II.[66] The volume of information shared by the Allied countries during the Second World War necessitated formal alignment of classification systems and procedural controls.[67] An arcane range of markings evolved to indicate who could handle documents (usually officers rather than enlisted troops) and where they should be stored as increasingly complex safes and storage facilities were developed.[68] The Enigma Machine, which was employed by the Germans to encrypt the data of warfare and was successfully decrypted by Alan Turing, can be regarded as a striking example of creating and using secured information.[69] Procedures evolved to ensure documents were destroyed properly, and it was the failure to follow these procedures which led to some of the greatest intelligence coups of the war (e.g., the capture of U-570[69]).

Various mainframe computers were connected online during the Cold War to complete more sophisticated tasks, in a communication process easier than mailing magnetic tapes back and forth by computer centers. As such, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), of the United States Department of Defense, started researching the feasibility of a networked system of communication to trade information within the United States Armed Forces. In 1968, the ARPANET project was formulated by Larry Roberts, which would later evolve into what is known as the internet.[70]

In 1973, important elements of ARPANET security were found by internet pioneer Robert Metcalfe to have many flaws such as the: "vulnerability of password structure and formats; lack of safety procedures for dial-up connections; and nonexistent user identification and authorizations", aside from the lack of controls and safeguards to keep data safe from unauthorized access. Hackers had effortless access to ARPANET, as phone numbers were known by the public.[71] Due to these problems, coupled with the constant violation of computer security, as well as the exponential increase in the number of hosts and users of the system, "network security" was often alluded to as "network insecurity".[71]

The end of the twentieth century and the early years of the twenty-first century saw rapid advancements in telecommunications, computing hardware and software, and data encryption.[72] The availability of smaller, more powerful, and less expensive computing equipment made electronic data processing within the reach of small business and home users.[73] The establishment of Transfer Control Protocol/Internetwork Protocol (TCP/IP) in the early 1980s enabled different types of computers to communicate.[74] These computers quickly became interconnected through the internet.[75]

The rapid growth and widespread use of electronic data processing and electronic business conducted through the internet, along with numerous occurrences of international terrorism, fueled the need for better methods of protecting the computers and the information they store, process, and transmit.[76] The academic disciplines of computer security and information assurance emerged along with numerous professional organizations, all sharing the common goals of ensuring the security and reliability of information systems.[citation needed]

Basic principles

Key concepts

The "CIA" triad of confidentiality, integrity, and availability is at the heart of information security.[77] (The members of the classic InfoSec triad—confidentiality, integrity, and availability—are interchangeably referred to in the literature as security attributes, properties, security goals, fundamental aspects, information criteria, critical information characteristics and basic building blocks.)[78] However, debate continues about whether or not this triad is sufficient to address rapidly changing technology and business requirements, with recommendations to consider expanding on the intersections between availability and confidentiality, as well as the relationship between security and privacy.[23] Other principles such as "accountability" have sometimes been proposed; it has been pointed out that issues such as non-repudiation do not fit well within the three core concepts.[79]

The triad seems to have first been mentioned in a NIST publication in 1977.[80]

In 1992 and revised in 2002, the OECD's Guidelines for the Security of Information Systems and Networks[81] proposed the nine generally accepted principles: awareness, responsibility, response, ethics, democracy, risk assessment, security design and implementation, security management, and reassessment.[82] Building upon those, in 2004 the NIST's Engineering Principles for Information Technology Security[79] proposed 33 principles. From each of these derived guidelines and practices.

In 1998, Donn Parker proposed an alternative model for the classic "CIA" triad that he called the six atomic elements of information. The elements are confidentiality, possession, integrity, authenticity, availability, and utility. The merits of the Parkerian Hexad are a subject of debate amongst security professionals.[83]

In 2011, The Open Group published the information security management standard O-ISM3.[84] This standard proposed an operational definition of the key concepts of security, with elements called "security objectives", related to access control (9), availability (3), data quality (1), compliance, and technical (4). In 2009, DoD Software Protection Initiative released the Three Tenets of Cybersecurity which are System Susceptibility, Access to the Flaw, and Capability to Exploit the Flaw.[85][86][87] Neither of these models are widely adopted.

Confidentiality

In information security, confidentiality "is the property, that information is not made available or disclosed to unauthorized individuals, entities, or processes."[88] While similar to "privacy," the two words are not interchangeable. Rather, confidentiality is a component of privacy that implements to protect our data from unauthorized viewers.[89] Examples of confidentiality of electronic data being compromised include laptop theft, password theft, or sensitive emails being sent to the incorrect individuals.[90]

Integrity

In IT security, data integrity means maintaining and assuring the accuracy and completeness of data over its entire lifecycle.[91] This means that data cannot be modified in an unauthorized or undetected manner.[92] This is not the same thing as referential integrity in databases, although it can be viewed as a special case of consistency as understood in the classic ACID model of transaction processing.[93] Information security systems typically incorporate controls to ensure their own integrity, in particular protecting the kernel or core functions against both deliberate and accidental threats.[94] Multi-purpose and multi-user computer systems aim to compartmentalize the data and processing such that no user or process can adversely impact another: the controls may not succeed however, as we see in incidents such as malware infections, hacks, data theft, fraud, and privacy breaches.[95]

More broadly, integrity is an information security principle that involves human/social, process, and commercial integrity, as well as data integrity. As such it touches on aspects such as credibility, consistency, truthfulness, completeness, accuracy, timeliness, and assurance.[96]

Availability

For any information system to serve its purpose, the information must be available when it is needed.[97] This means the computing systems used to store and process the information, the security controls used to protect it, and the communication channels used to access it must be functioning correctly.[98] High availability systems aim to remain available at all times, preventing service disruptions due to power outages, hardware failures, and system upgrades.[99] Ensuring availability also involves preventing denial-of-service attacks, such as a flood of incoming messages to the target system, essentially forcing it to shut down.[100]

In the realm of information security, availability can often be viewed as one of the most important parts of a successful information security program.[citation needed] Ultimately end-users need to be able to perform job functions; by ensuring availability an organization is able to perform to the standards that an organization's stakeholders expect.[101] This can involve topics such as proxy configurations, outside web access, the ability to access shared drives and the ability to send emails.[102] Executives oftentimes do not understand the technical side of information security and look at availability as an easy fix, but this often requires collaboration from many different organizational teams, such as network operations, development operations, incident response, and policy/change management.[103] A successful information security team involves many different key roles to mesh and align for the "CIA" triad to be provided effectively.[104]

Non-repudiation

In law, non-repudiation implies one's intention to fulfill their obligations to a contract. It also implies that one party of a transaction cannot deny having received a transaction, nor can the other party deny having sent a transaction.[105]

It is important to note that while technology such as cryptographic systems can assist in non-repudiation efforts, the concept is at its core a legal concept transcending the realm of technology.[106] It is not, for instance, sufficient to show that the message matches a digital signature signed with the sender's private key, and thus only the sender could have sent the message, and nobody else could have altered it in transit (data integrity).[107] The alleged sender could in return demonstrate that the digital signature algorithm is vulnerable or flawed, or allege or prove that his signing key has been compromised.[108] The fault for these violations may or may not lie with the sender, and such assertions may or may not relieve the sender of liability, but the assertion would invalidate the claim that the signature necessarily proves authenticity and integrity. As such, the sender may repudiate the message (because authenticity and integrity are pre-requisites for non-repudiation).[109]

Risk management

Broadly speaking, risk is the likelihood that something bad will happen that causes harm to an informational asset (or the loss of the asset).[110] A vulnerability is a weakness that could be used to endanger or cause harm to an informational asset. A threat is anything (man-made or act of nature) that has the potential to cause harm.[111] The likelihood that a threat will use a vulnerability to cause harm creates a risk. When a threat does use a vulnerability to inflict harm, it has an impact.[112] In the context of information security, the impact is a loss of availability, integrity, and confidentiality, and possibly other losses (lost income, loss of life, loss of real property).[113]

The Certified Information Systems Auditor (CISA) Review Manual 2006 defines risk management as "the process of identifying vulnerabilities and threats to the information resources used by an organization in achieving business objectives, and deciding what countermeasures,[114] if any, to take in reducing risk to an acceptable level, based on the value of the information resource to the organization."[115]

There are two things in this definition that may need some clarification. First, the process of risk management is an ongoing, iterative process. It must be repeated indefinitely. The business environment is constantly changing and new threats and vulnerabilities emerge every day.[116] Second, the choice of countermeasures (controls) used to manage risks must strike a balance between productivity, cost, effectiveness of the countermeasure, and the value of the informational asset being protected.[117] Furthermore, these processes have limitations as security breaches are generally rare and emerge in a specific context which may not be easily duplicated.[118] Thus, any process and countermeasure should itself be evaluated for vulnerabilities.[119] It is not possible to identify all risks, nor is it possible to eliminate all risk. The remaining risk is called "residual risk".[120]

A risk assessment is carried out by a team of people who have knowledge of specific areas of the business.[121] Membership of the team may vary over time as different parts of the business are assessed.[122] The assessment may use a subjective qualitative analysis based on informed opinion, or where reliable dollar figures and historical information is available, the analysis may use quantitative analysis.

Research has shown that the most vulnerable point in most information systems is the human user, operator, designer, or other human.[123] The ISO/IEC 27002:2005 Code of practice for information security management recommends the following be examined during a risk assessment:

- security policy,

- organization of information security,

- asset management,

- human resources security,

- physical and environmental security,

- communications and operations management,

- access control,

- information systems acquisition, development, and maintenance,

- information security incident management,

- business continuity management

- regulatory compliance.

In broad terms, the risk management process consists of:[124][125]

- Identification of assets and estimating their value. Include: people, buildings, hardware, software, data (electronic, print, other), supplies.[126]

- Conduct a threat assessment. Include: Acts of nature, acts of war, accidents, malicious acts originating from inside or outside the organization.[127]

- Conduct a vulnerability assessment, and for each vulnerability, calculate the probability that it will be exploited. Evaluate policies, procedures, standards, training, physical security, quality control, technical security.[128]

- Calculate the impact that each threat would have on each asset. Use qualitative analysis or quantitative analysis.[129]

- Identify, select and implement appropriate controls. Provide a proportional response. Consider productivity, cost effectiveness, and value of the asset.[130]

- Evaluate the effectiveness of the control measures. Ensure the controls provide the required cost effective protection without discernible loss of productivity.[131]

For any given risk, management can choose to accept the risk based upon the relative low value of the asset, the relative low frequency of occurrence, and the relative low impact on the business.[132] Or, leadership may choose to mitigate the risk by selecting and implementing appropriate control measures to reduce the risk. In some cases, the risk can be transferred to another business by buying insurance or outsourcing to another business.[133] The reality of some risks may be disputed. In such cases leadership may choose to deny the risk.[134]

Security controls

Selecting and implementing proper security controls will initially help an organization bring down risk to acceptable levels.[135] Control selection should follow and should be based on the risk assessment.[136] Controls can vary in nature, but fundamentally they are ways of protecting the confidentiality, integrity or availability of information. ISO/IEC 27001 has defined controls in different areas.[137] Organizations can implement additional controls according to requirement of the organization.[138] ISO/IEC 27002 offers a guideline for organizational information security standards.[139]

Administrative

Administrative controls (also called procedural controls) consist of approved written policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines. Administrative controls form the framework for running the business and managing people.[140] They inform people on how the business is to be run and how day-to-day operations are to be conducted. Laws and regulations created by government bodies are also a type of administrative control because they inform the business.[141] Some industry sectors have policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines that must be followed – the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard[142] (PCI DSS) required by Visa and MasterCard is such an example. Other examples of administrative controls include the corporate security policy, password policy, hiring policies, and disciplinary policies.[143]

Administrative controls form the basis for the selection and implementation of logical and physical controls. Logical and physical controls are manifestations of administrative controls, which are of paramount importance.[140]

Logical

Logical controls (also called technical controls) use software and data to monitor and control access to information and computing systems.[citation needed] Passwords, network and host-based firewalls, network intrusion detection systems, access control lists, and data encryption are examples of logical controls.[144]

An important logical control that is frequently overlooked is the principle of least privilege, which requires that an individual, program or system process not be granted any more access privileges than are necessary to perform the task.[145] A blatant example of the failure to adhere to the principle of least privilege is logging into Windows as user Administrator to read email and surf the web. Violations of this principle can also occur when an individual collects additional access privileges over time.[146] This happens when employees' job duties change, employees are promoted to a new position, or employees are transferred to another department.[147] The access privileges required by their new duties are frequently added onto their already existing access privileges, which may no longer be necessary or appropriate.[148]

Physical

Physical controls monitor and control the environment of the work place and computing facilities.[149] They also monitor and control access to and from such facilities and include doors, locks, heating and air conditioning, smoke and fire alarms, fire suppression systems, cameras, barricades, fencing, security guards, cable locks, etc. Separating the network and workplace into functional areas are also physical controls.[150]

An important physical control that is frequently overlooked is separation of duties, which ensures that an individual can not complete a critical task by himself.[151] For example, an employee who submits a request for reimbursement should not also be able to authorize payment or print the check.[152] An applications programmer should not also be the server administrator or the database administrator; these roles and responsibilities must be separated from one another.[153]

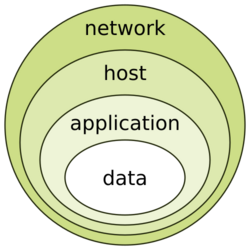

Defense in depth

Information security must protect information throughout its lifespan, from the initial creation of the information on through to the final disposal of the information.[154] The information must be protected while in motion and while at rest. During its lifetime, information may pass through many different information processing systems and through many different parts of information processing systems.[155] There are many different ways the information and information systems can be threatened. To fully protect the information during its lifetime, each component of the information processing system must have its own protection mechanisms.[156] The building up, layering on, and overlapping of security measures is called "defense in depth."[157] In contrast to a metal chain, which is famously only as strong as its weakest link, the defense in depth strategy aims at a structure where, should one defensive measure fail, other measures will continue to provide protection.[158]

Recall the earlier discussion about administrative controls, logical controls, and physical controls. The three types of controls can be used to form the basis upon which to build a defense in depth strategy.[140] With this approach, defense in depth can be conceptualized as three distinct layers or planes laid one on top of the other.[159] Additional insight into defense in depth can be gained by thinking of it as forming the layers of an onion, with data at the core of the onion, people the next outer layer of the onion, and network security, host-based security, and application security forming the outermost layers of the onion.[160] Both perspectives are equally valid, and each provides valuable insight into the implementation of a good defense in depth strategy.[161]

Classification

An important aspect of information security and risk management is recognizing the value of information and defining appropriate procedures and protection requirements for the information.[162] Not all information is equal and so not all information requires the same degree of protection.[163] This requires information to be assigned a security classification.[164] The first step in information classification is to identify a member of senior management as the owner of the particular information to be classified. Next, develop a classification policy.[165] The policy should describe the different classification labels, define the criteria for information to be assigned a particular label, and list the required security controls for each classification.[166]

Some factors that influence which classification information should be assigned include how much value that information has to the organization, how old the information is and whether or not the information has become obsolete.[167] Laws and other regulatory requirements are also important considerations when classifying information.[168] The Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA) and its Business Model for Information Security also serves as a tool for security professionals to examine security from a systems perspective, creating an environment where security can be managed holistically, allowing actual risks to be addressed.[169]

The type of information security classification labels selected and used will depend on the nature of the organization, with examples being:[166]

- In the business sector, labels such as: Public, Sensitive, Private, Confidential.

- In the government sector, labels such as: Unclassified, Unofficial, Protected, Confidential, Secret, Top Secret, and their non-English equivalents.[170]

- In cross-sectoral formations, the Traffic Light Protocol, which consists of: White, Green, Amber, and Red.

- In the personal sector, one label such as Financial. This includes activities related to managing money, such as online banking.[171]

All employees in the organization, as well as business partners, must be trained on the classification schema and understand the required security controls and handling procedures for each classification.[172] The classification of a particular information asset that has been assigned should be reviewed periodically to ensure the classification is still appropriate for the information and to ensure the security controls required by the classification are in place and are followed in their right procedures.[173]

Access control

Access to protected information must be restricted to people who are authorized to access the information.[174] The computer programs, and in many cases the computers that process the information, must also be authorized.[175] This requires that mechanisms be in place to control the access to protected information.[175] The sophistication of the access control mechanisms should be in parity with the value of the information being protected; the more sensitive or valuable the information the stronger the control mechanisms need to be.[176] The foundation on which access control mechanisms are built start with identification and authentication.[177]

Access control is generally considered in three steps: identification, authentication, and authorization.[178][90]

Identification

Identification is an assertion of who someone is or what something is. If a person makes the statement "Hello, my name is John Doe" they are making a claim of who they are.[179] However, their claim may or may not be true. Before John Doe can be granted access to protected information it will be necessary to verify that the person claiming to be John Doe really is John Doe.[180] Typically the claim is in the form of a username. By entering that username you are claiming "I am the person the username belongs to".[181]

Authentication

Authentication is the act of verifying a claim of identity. When John Doe goes into a bank to make a withdrawal, he tells the bank teller he is John Doe, a claim of identity.[182] The bank teller asks to see a photo ID, so he hands the teller his driver's license.[183] The bank teller checks the license to make sure it has John Doe printed on it and compares the photograph on the license against the person claiming to be John Doe.[184] If the photo and name match the person, then the teller has authenticated that John Doe is who he claimed to be. Similarly, by entering the correct password, the user is providing evidence that he/she is the person the username belongs to.[185]

There are three different types of information that can be used for authentication:[186][187]

- Something you know: things such as a PIN, a password, or your mother's maiden name[188][189]

- Something you have: a driver's license or a magnetic swipe card[190][191]

- Something you are: biometrics, including palm prints, fingerprints, voice prints, and retina (eye) scans[192]

Strong authentication requires providing more than one type of authentication information (two-factor authentication).[193] The username is the most common form of identification on computer systems today and the password is the most common form of authentication.[194] Usernames and passwords have served their purpose, but they are increasingly inadequate.[195] Usernames and passwords are slowly being replaced or supplemented with more sophisticated authentication mechanisms such as time-based one-time password algorithms.[196]

Authorization

After a person, program or computer has successfully been identified and authenticated then it must be determined what informational resources they are permitted to access and what actions they will be allowed to perform (run, view, create, delete, or change).[197] This is called authorization. Authorization to access information and other computing services begins with administrative policies and procedures.[198] The policies prescribe what information and computing services can be accessed, by whom, and under what conditions. The access control mechanisms are then configured to enforce these policies.[199] Different computing systems are equipped with different kinds of access control mechanisms. Some may even offer a choice of different access control mechanisms.[200] The access control mechanism a system offers will be based upon one of three approaches to access control, or it may be derived from a combination of the three approaches.[90]

The non-discretionary approach consolidates all access control under a centralized administration.[201] The access to information and other resources is usually based on the individuals function (role) in the organization or the tasks the individual must perform.[202][203] The discretionary approach gives the creator or owner of the information resource the ability to control access to those resources.[201] In the mandatory access control approach, access is granted or denied basing upon the security classification assigned to the information resource.[174]

Examples of common access control mechanisms in use today include role-based access control, available in many advanced database management systems; simple file permissions provided in the UNIX and Windows operating systems;[204] Group Policy Objects provided in Windows network systems; and Kerberos, RADIUS, TACACS, and the simple access lists used in many firewalls and routers.[205]

To be effective, policies and other security controls must be enforceable and upheld. Effective policies ensure that people are held accountable for their actions.[206] The U.S. Treasury's guidelines for systems processing sensitive or proprietary information, for example, states that all failed and successful authentication and access attempts must be logged, and all access to information must leave some type of audit trail.[207]

Also, the need-to-know principle needs to be in effect when talking about access control. This principle gives access rights to a person to perform their job functions.[208] This principle is used in the government when dealing with difference clearances.[209] Even though two employees in different departments have a top-secret clearance, they must have a need-to-know in order for information to be exchanged. Within the need-to-know principle, network administrators grant the employee the least amount of privilege to prevent employees from accessing more than what they are supposed to.[210] Need-to-know helps to enforce the confidentiality-integrity-availability triad. Need-to-know directly impacts the confidential area of the triad.[211]

Cryptography

Information security uses cryptography to transform usable information into a form that renders it unusable by anyone other than an authorized user; this process is called encryption.[212] Information that has been encrypted (rendered unusable) can be transformed back into its original usable form by an authorized user who possesses the cryptographic key, through the process of decryption.[213] Cryptography is used in information security to protect information from unauthorized or accidental disclosure while the information is in transit (either electronically or physically) and while information is in storage.[90]

Cryptography provides information security with other useful applications as well, including improved authentication methods, message digests, digital signatures, non-repudiation, and encrypted network communications.[214] Older, less secure applications such as Telnet and File Transfer Protocol (FTP) are slowly being replaced with more secure applications such as Secure Shell (SSH) that use encrypted network communications.[215] Wireless communications can be encrypted using protocols such as WPA/WPA2 or the older (and less secure) WEP. Wired communications (such as ITU‑T G.hn) are secured using AES for encryption and X.1035 for authentication and key exchange.[216] Software applications such as GnuPG or PGP can be used to encrypt data files and email.[217]

Cryptography can introduce security problems when it is not implemented correctly.[218] Cryptographic solutions need to be implemented using industry-accepted solutions that have undergone rigorous peer review by independent experts in cryptography.[219] The length and strength of the encryption key is also an important consideration.[220] A key that is weak or too short will produce weak encryption.[220] The keys used for encryption and decryption must be protected with the same degree of rigor as any other confidential information.[221] They must be protected from unauthorized disclosure and destruction, and they must be available when needed.[citation needed] Public key infrastructure (PKI) solutions address many of the problems that surround key management.[90]

Process

The terms "reasonable and prudent person", "due care", and "due diligence" have been used in the fields of finance, securities, and law for many years. In recent years these terms have found their way into the fields of computing and information security.[125] U.S. Federal Sentencing Guidelines now make it possible to hold corporate officers liable for failing to exercise due care and due diligence in the management of their information systems.[222]

In the business world, stockholders, customers, business partners, and governments have the expectation that corporate officers will run the business in accordance with accepted business practices and in compliance with laws and other regulatory requirements. This is often described as the "reasonable and prudent person" rule. A prudent person takes due care to ensure that everything necessary is done to operate the business by sound business principles and in a legal, ethical manner. A prudent person is also diligent (mindful, attentive, ongoing) in their due care of the business.

In the field of information security, Harris[223] offers the following definitions of due care and due diligence:

"Due care are steps that are taken to show that a company has taken responsibility for the activities that take place within the corporation and has taken the necessary steps to help protect the company, its resources, and employees[224]." And, [Due diligence are the] "continual activities that make sure the protection mechanisms are continually maintained and operational."[225]

Attention should be made to two important points in these definitions.[226][227] First, in due care, steps are taken to show; this means that the steps can be verified, measured, or even produce tangible artifacts.[228][229] Second, in due diligence, there are continual activities; this means that people are actually doing things to monitor and maintain the protection mechanisms, and these activities are ongoing.[230]

Organizations have a responsibility with practicing duty of care when applying information security. The Duty of Care Risk Analysis Standard (DoCRA)[231] provides principles and practices for evaluating risk.[232] It considers all parties that could be affected by those risks.[233] DoCRA helps evaluate safeguards if they are appropriate in protecting others from harm while presenting a reasonable burden.[234] With increased data breach litigation, companies must balance security controls, compliance, and its mission.[235]

Security governance

The Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, in a publication titled Governing for Enterprise Security (GES) Implementation Guide, defines characteristics of effective security governance. These include:[236]

- An enterprise-wide issue

- Leaders are accountable

- Viewed as a business requirement

- Risk-based

- Roles, responsibilities, and segregation of duties defined

- Addressed and enforced in policy

- Adequate resources committed

- Staff aware and trained

- A development life cycle requirement

- Planned, managed, measurable, and measured

- Reviewed and audited

Incident response plans

An incident response plan (IRP) is a group of policies that dictate an organizations reaction to a cyber attack. Once an security breach has been identified, for example by network intrusion detection system (NIDS) or host-based intrusion detection system (HIDS) (if configured to do so), the plan is initiated.[237] It is important to note that there can be legal implications to a data breach. Knowing local and federal laws is critical.[238] Every plan is unique to the needs of the organization, and it can involve skill sets that are not part of an IT team.[239] For example, a lawyer may be included in the response plan to help navigate legal implications to a data breach.[citation needed]

As mentioned above every plan is unique but most plans will include the following:[240]

Preparation

Good preparation includes the development of an incident response team (IRT).[241] Skills need to be used by this team would be, penetration testing, computer forensics, network security, etc.[242] This team should also keep track of trends in cybersecurity and modern attack strategies.[243] A training program for end users is important as well as most modern attack strategies target users on the network.[240]

Identification

This part of the incident response plan identifies if there was a security event.[244] When an end user reports information or an admin notices irregularities, an investigation is launched. An incident log is a crucial part of this step.[citation needed] All of the members of the team should be updating this log to ensure that information flows as fast as possible.[245] If it has been identified that a security breach has occurred the next step should be activated.[246]

Containment

In this phase, the IRT works to isolate the areas that the breach took place to limit the scope of the security event.[247] During this phase it is important to preserve information forensically so it can be analyzed later in the process.[248] Containment could be as simple as physically containing a server room or as complex as segmenting a network to not allow the spread of a virus.[249]

Eradication

This is where the threat that was identified is removed from the affected systems.[250] This could include deleting malicious files, terminating compromised accounts, or deleting other components.[251][252] Some events do not require this step, however it is important to fully understand the event before moving to this step.[253] This will help to ensure that the threat is completely removed.[249]

Recovery

This stage is where the systems are restored back to original operation.[254] This stage could include the recovery of data, changing user access information, or updating firewall rules or policies to prevent a breach in the future.[255][256] Without executing this step, the system could still be vulnerable to future security threats.[249]

Lessons learned

In this step information that has been gathered during this process is used to make future decisions on security.[257] This step is crucial to the ensure that future events are prevented. Using this information to further train admins is critical to the process.[258] This step can also be used to process information that is distributed from other entities who have experienced a security event.[259]

Change management

Change management is a formal process for directing and controlling alterations to the information processing environment.[260][261] This includes alterations to desktop computers, the network, servers, and software.[262] The objectives of change management are to reduce the risks posed by changes to the information processing environment and improve the stability and reliability of the processing environment as changes are made.[263] It is not the objective of change management to prevent or hinder necessary changes from being implemented.[264][265]

Any change to the information processing environment introduces an element of risk.[266] Even apparently simple changes can have unexpected effects.[267] One of management's many responsibilities is the management of risk.[268][269] Change management is a tool for managing the risks introduced by changes to the information processing environment.[270] Part of the change management process ensures that changes are not implemented at inopportune times when they may disrupt critical business processes or interfere with other changes being implemented.[271]

Not every change needs to be managed.[272][273] Some kinds of changes are a part of the everyday routine of information processing and adhere to a predefined procedure, which reduces the overall level of risk to the processing environment.[274] Creating a new user account or deploying a new desktop computer are examples of changes that do not generally require change management.[275] However, relocating user file shares, or upgrading the Email server pose a much higher level of risk to the processing environment and are not a normal everyday activity.[276] The critical first steps in change management are (a) defining change (and communicating that definition) and (b) defining the scope of the change system.[277]

Change management is usually overseen by a change review board composed of representatives from key business areas,[278] security, networking, systems administrators, database administration, application developers, desktop support, and the help desk.[279] The tasks of the change review board can be facilitated with the use of automated work flow application.[280] The responsibility of the change review board is to ensure the organization's documented change management procedures are followed.[281] The change management process is as follows[282]

- Request: Anyone can request a change.[283][284] The person making the change request may or may not be the same person that performs the analysis or implements the change.[285][286] When a request for change is received, it may undergo a preliminary review to determine if the requested change is compatible with the organizations business model and practices, and to determine the amount of resources needed to implement the change.[287]

- Approve: Management runs the business and controls the allocation of resources therefore, management must approve requests for changes and assign a priority for every change.[288] Management might choose to reject a change request if the change is not compatible with the business model, industry standards or best practices.[289][290] Management might also choose to reject a change request if the change requires more resources than can be allocated for the change.[291]

- Plan: Planning a change involves discovering the scope and impact of the proposed change; analyzing the complexity of the change; allocation of resources and, developing, testing, and documenting both implementation and back-out plans.[292] Need to define the criteria on which a decision to back out will be made.[293]

- Test: Every change must be tested in a safe test environment, which closely reflects the actual production environment, before the change is applied to the production environment.[294] The backout plan must also be tested.[295]

- Schedule: Part of the change review board's responsibility is to assist in the scheduling of changes by reviewing the proposed implementation date for potential conflicts with other scheduled changes or critical business activities.[296]

- Communicate: Once a change has been scheduled it must be communicated.[297] The communication is to give others the opportunity to remind the change review board about other changes or critical business activities that might have been overlooked when scheduling the change.[298] The communication also serves to make the help desk and users aware that a change is about to occur.[299] Another responsibility of the change review board is to ensure that scheduled changes have been properly communicated to those who will be affected by the change or otherwise have an interest in the change.[300][301]

- Implement: At the appointed date and time, the changes must be implemented.[302][303] Part of the planning process was to develop an implementation plan, testing plan and, a back out plan.[304][305] If the implementation of the change should fail or, the post implementation testing fails or, other "drop dead" criteria have been met, the back out plan should be implemented.[306]

- Document: All changes must be documented.[307][308] The documentation includes the initial request for change, its approval, the priority assigned to it, the implementation,[309] testing and back out plans, the results of the change review board critique, the date/time the change was implemented,[310] who implemented it, and whether the change was implemented successfully, failed or postponed.[311][312]

- Post-change review: The change review board should hold a post-implementation review of changes.[313] It is particularly important to review failed and backed out changes. The review board should try to understand the problems that were encountered, and look for areas for improvement.[313]

Change management procedures that are simple to follow and easy to use can greatly reduce the overall risks created when changes are made to the information processing environment.[314] Good change management procedures improve the overall quality and success of changes as they are implemented.[315] This is accomplished through planning, peer review, documentation, and communication.[316]

ISO/IEC 20000, The Visible OPS Handbook: Implementing ITIL in 4 Practical and Auditable Steps[317] (Full book summary),[318] and ITIL all provide valuable guidance on implementing an efficient and effective change management program information security.[319]

Business continuity

Business continuity management (BCM) concerns arrangements aiming to protect an organization's critical business functions from interruption due to incidents, or at least minimize the effects.[320][321] BCM is essential to any organization to keep technology and business in line with current threats to the continuation of business as usual.[322] The BCM should be included in an organizations risk analysis plan to ensure that all of the necessary business functions have what they need to keep going in the event of any type of threat to any business function.[323]

It encompasses:

- Analysis of requirements, e.g., identifying critical business functions, dependencies and potential failure points, potential threats and hence incidents or risks of concern to the organization;[324][325]

- Specification, e.g., maximum tolerable outage periods; recovery point objectives (maximum acceptable periods of data loss);[326]

- Architecture and design, e.g., an appropriate combination of approaches including resilience (e.g. engineering IT systems and processes for high availability,[327] avoiding or preventing situations that might interrupt the business), incident and emergency management (e.g., evacuating premises, calling the emergency services, triage/situation[328] assessment and invoking recovery plans), recovery (e.g., rebuilding) and contingency management (generic capabilities to deal positively with whatever occurs using whatever resources are available);[329]

- Implementation, e.g., configuring and scheduling backups, data transfers, etc., duplicating and strengthening critical elements; contracting with service and equipment suppliers;

- Testing, e.g., business continuity exercises of various types, costs and assurance levels;[330]

- Management, e.g., defining strategies, setting objectives and goals; planning and directing the work; allocating funds, people and other resources; prioritization relative to other activities; team building, leadership, control, motivation and coordination with other business functions and activities[331] (e.g., IT, facilities, human resources, risk management, information risk and security, operations); monitoring the situation, checking and updating the arrangements when things change; maturing the approach through continuous improvement, learning and appropriate investment;[citation needed]

- Assurance, e.g., testing against specified requirements; measuring, analyzing, and reporting key parameters; conducting additional tests, reviews and audits for greater confidence that the arrangements will go to plan if invoked.[332]

Whereas BCM takes a broad approach to minimizing disaster-related risks by reducing both the probability and the severity of incidents, a disaster recovery plan (DRP) focuses specifically on resuming business operations as quickly as possible after a disaster.[333] A disaster recovery plan, invoked soon after a disaster occurs, lays out the steps necessary to recover critical information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure.[334] Disaster recovery planning includes establishing a planning group, performing risk assessment, establishing priorities, developing recovery strategies, preparing inventories and documentation of the plan, developing verification criteria and procedure, and lastly implementing the plan.[335]

Laws and regulations

Below is a partial listing of governmental laws and regulations in various parts of the world that have, had, or will have, a significant effect on data processing and information security.[336][337] Important industry sector regulations have also been included when they have a significant impact on information security.[336]

- The UK Data Protection Act 1998 makes new provisions for the regulation of the processing of information relating to individuals, including the obtaining, holding, use or disclosure of such information.[338][339] The European Union Data Protection Directive (EUDPD) requires that all E.U. members adopt national regulations to standardize the protection of data privacy for citizens throughout the E.U.[340][341]

- The Computer Misuse Act 1990 is an Act of the U.K. Parliament making computer crime (e.g., hacking) a criminal offense.[342] The act has become a model upon which several other countries,[343] including Canada and the Republic of Ireland, have drawn inspiration from when subsequently drafting their own information security laws.[344][345]

- The E.U.'s Data Retention Directive (annulled) required internet service providers and phone companies to keep data on every electronic message sent and phone call made for between six months and two years.[346]

- The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) (20 U.S.C. § 1232 g; 34 CFR Part 99) is a U.S. Federal law that protects the privacy of student education records.[347] The law applies to all schools that receive funds under an applicable program of the U.S. Department of Education.[348] Generally, schools must have written permission from the parent or eligible student[348][349] in order to release any information from a student's education record.[350]

- The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council's (FFIEC) security guidelines for auditors specifies requirements for online banking security.[351]

- The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 requires the adoption of national standards for electronic health care transactions and national identifiers for providers, health insurance plans, and employers.[352] Additionally, it requires health care providers, insurance providers and employers to safeguard the security and privacy of health data.[353]

- The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act of 1999 (GLBA), also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, protects the privacy and security of private financial information that financial institutions collect, hold, and process.[354]

- Section 404 of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) requires publicly traded companies to assess the effectiveness of their internal controls for financial reporting in annual reports they submit at the end of each fiscal year.[355] Chief information officers are responsible for the security, accuracy, and the reliability of the systems that manage and report the financial data.[356] The act also requires publicly traded companies to engage with independent auditors who must attest to, and report on, the validity of their assessments.[357]

- The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) establishes comprehensive requirements for enhancing payment account data security.[358] It was developed by the founding payment brands of the PCI Security Standards Council — including American Express, Discover Financial Services, JCB, MasterCard Worldwide,[359] and Visa International — to help facilitate the broad adoption of consistent data security measures on a global basis.[360] The PCI DSS is a multifaceted security standard that includes requirements for security management, policies, procedures, network architecture, software design, and other critical protective measures.[361]

- State security breach notification laws (California and many others) require businesses, nonprofits, and state institutions to notify consumers when unencrypted "personal information" may have been compromised, lost, or stolen.[362]

- The Personal Information Protection and Electronics Document Act (PIPEDA) of Canada supports and promotes electronic commerce by protecting personal information that is collected, used or disclosed in certain circumstances,[363][364] by providing for the use of electronic means to communicate or record information or transactions and by amending the Canada Evidence Act, the Statutory Instruments Act and the Statute Revision Act.[365][366][367]

- Greece's Hellenic Authority for Communication Security and Privacy (ADAE) (Law 165/2011) establishes and describes the minimum information security controls that should be deployed by every company which provides electronic communication networks and/or services in Greece in order to protect customers' confidentiality.[368] These include both managerial and technical controls (e.g., log records should be stored for two years).[369]

- Greece's Hellenic Authority for Communication Security and Privacy (ADAE) (Law 205/2013) concentrates around the protection of the integrity and availability of the services and data offered by Greek telecommunication companies.[370] The law forces these and other related companies to build, deploy, and test appropriate business continuity plans and redundant infrastructures.[371]

The US Department of Defense (DoD) issued DoD Directive 8570 in 2004, supplemented by DoD Directive 8140, requiring all DoD employees and all DoD contract personnel involved in information assurance roles and activities to earn and maintain various industry Information Technology (IT) certifications in an effort to ensure that all DoD personnel involved in network infrastructure defense have minimum levels of IT industry recognized knowledge, skills and abilities (KSA). Andersson and Reimers (2019) report these certifications range from CompTIA's A+ and Security+ through the ICS2.org's CISSP, etc.[372]

Culture

Describing more than simply how security aware employees are, information security culture is the ideas, customs, and social behaviors of an organization that impact information security in both positive and negative ways.[373] Cultural concepts can help different segments of the organization work effectively or work against effectiveness towards information security within an organization. The way employees think and feel about security and the actions they take can have a big impact on information security in organizations. Roer & Petric (2017) identify seven core dimensions of information security culture in organizations:[374]

- Attitudes: employees' feelings and emotions about the various activities that pertain to the organizational security of information.[375]

- Behaviors: actual or intended activities and risk-taking actions of employees that have direct or indirect impact on information security.

- Cognition: employees' awareness, verifiable knowledge, and beliefs regarding practices, activities, and self-efficacy relation that are related to information security.

- Communication: ways employees communicate with each other, sense of belonging, support for security issues, and incident reporting.

- Compliance: adherence to organizational security policies, awareness of the existence of such policies and the ability to recall the substance of such policies.

- Norms: perceptions of security-related organizational conduct and practices that are informally deemed either normal or deviant by employees and their peers, e.g. hidden expectations regarding security behaviors and unwritten rules regarding uses of information-communication technologies.

- Responsibilities: employees' understanding of the roles and responsibilities they have as a critical factor in sustaining or endangering the security of information, and thereby the organization.

Andersson and Reimers (2014) found that employees often do not see themselves as part of the organization Information Security "effort" and often take actions that ignore organizational information security best interests.[376] Research shows information security culture needs to be improved continuously. In Information Security Culture from Analysis to Change, authors commented, "It's a never ending process, a cycle of evaluation and change or maintenance." To manage the information security culture, five steps should be taken: pre-evaluation, strategic planning, operative planning, implementation, and post-evaluation.[377]

- Pre-evaluation: to identify the awareness of information security within employees and to analyze current security policy

- Strategic planning: to come up a better awareness-program, we need to set clear targets. Clustering people is helpful to achieve it

- Operative planning: create a good security culture based on internal communication, management buy-in, security awareness, and training programs

- Implementation: should feature commitment of management, communication with organizational members, courses for all organizational members, and commitment of the employees[377]

- Post-evaluation: to better gauge the effectiveness of the prior steps and build on continuous improvement

Sources of standards

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is an international standards organization organized as a consortium of national standards institutions from 167 countries, coordinated through a secretariat in Geneva, Switzerland. ISO is the world's largest developer of international standards. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is an international standards organization that deals with electrotechnology and cooperates closely with ISO. ISO/IEC 15443: "Information technology – Security techniques – A framework for IT security assurance", ISO/IEC 27002: "Information technology – Security techniques – Code of practice for information security management", ISO/IEC 20000: "Information technology – Service management", and ISO/IEC 27001: "Information technology – Security techniques – Information security management systems – Requirements" are of particular interest to information security professionals.

The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is a non-regulatory federal agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce. The NIST Computer Security Division develops standards, metrics, tests, and validation programs as well as publishes standards and guidelines to increase secure IT planning, implementation, management, and operation. NIST is also the custodian of the U.S. Federal Information Processing Standard publications (FIPS).

The Internet Society is a professional membership society with more than 100 organizations and over 20,000 individual members in over 180 countries. It provides leadership in addressing issues that confront the future of the internet, and it is the organizational home for the groups responsible for internet infrastructure standards, including the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and the Internet Architecture Board (IAB). The ISOC hosts the Requests for Comments (RFCs) which includes the Official Internet Protocol Standards and the RFC-2196 Site Security Handbook.

The Information Security Forum (ISF) is a global nonprofit organization of several hundred leading organizations in financial services, manufacturing, telecommunications, consumer goods, government, and other areas. It undertakes research into information security practices and offers advice in its biannual Standard of Good Practice for Information Security and more detailed advisories for members.

The Institute of Information Security Professionals (IISP) is an independent, non-profit body governed by its members, with the principal objective of advancing the professionalism of information security practitioners and thereby the professionalism of the industry as a whole. The institute developed the IISP Skills Framework. This framework describes the range of competencies expected of information security and information assurance professionals in the effective performance of their roles. It was developed through collaboration between both private and public sector organizations, world-renowned academics, and security leaders.[378]

The German Federal Office for Information Security (in German Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik (BSI)) BSI-Standards 100–1 to 100-4 are a set of recommendations including "methods, processes, procedures, approaches and measures relating to information security".[379] The BSI-Standard 100-2 IT-Grundschutz Methodology describes how information security management can be implemented and operated. The standard includes a very specific guide, the IT Baseline Protection Catalogs (also known as IT-Grundschutz Catalogs). Before 2005, the catalogs were formerly known as "IT Baseline Protection Manual". The Catalogs are a collection of documents useful for detecting and combating security-relevant weak points in the IT environment (IT cluster). The collection encompasses as of September 2013 over 4,400 pages with the introduction and catalogs. The IT-Grundschutz approach is aligned with to the ISO/IEC 2700x family.

The European Telecommunications Standards Institute standardized a catalog of information security indicators, headed by the Industrial Specification Group (ISG) ISI.

See also

- Backup

- Capability-based security

- Computer security (cybersecurity)

- Data breach

- Data-centric security

- Enterprise information security architecture

- Identity-based security

- Information infrastructure

- Information security audit

- Information security indicators

- Information security management

- Information security standards

- Information technology

- Information technology security audit

- IT risk

- ITIL security management

- Kill chain

- List of computer security certifications

- Mobile security

- Network Security Services

- Privacy engineering

- Privacy software

- Privacy-enhancing technologies

- Security bug

- Security convergence

- Security information management

- Security level management

- Security of Information Act

- Security service (telecommunication)

- Single sign-on

- Verification and validation

- Gordon–Loeb model for cyber security investments

References

- ↑ Curry, Michael; Marshall, Byron; Crossler, Robert E.; Correia, John (2018-04-25). "InfoSec Process Action Model (IPAM): Systematically Addressing Individual Security Behavior" (in en). ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems 49 (SI): 49–66. doi:10.1145/3210530.3210535. ISSN 0095-0033. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3210530.3210535.

- ↑ Joshi, Chanchala; Singh, Umesh Kumar (August 2017). "Information security risks management framework – A step towards mitigating security risks in university network". Journal of Information Security and Applications 35: 128–137. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2017.06.006. ISSN 2214-2126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jisa.2017.06.006.

- ↑ Fletcher, Martin (14 December 2016). "An introduction to information risk". https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/introduction-information-risk/.

- ↑ Daniel, Kent; Titman, Sheridan (August 2006). "Market Reactions to Tangible and Intangible Information". The Journal of Finance 61 (4): 1605–1643. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00884.x. https://www.nber.org/papers/w9743.

- ↑ Fink, Kerstin (2004). Knowledge Potential Measurement and Uncertainty. Deutscher Universitätsverlag. ISBN 978-3-322-81240-7. OCLC 851734708.

- ↑ Keyser, Tobias (2018-04-19), "Security policy", The Information Governance Toolkit (CRC Press): pp. 57–62, doi:10.1201/9781315385488-13, ISBN 978-1-315-38548-8, http://dx.doi.org/10.1201/9781315385488-13, retrieved 2021-05-28

- ↑ Danzig, Richard; National Defense University Washington DC Inst for National Strategic Studies (1995). "The big three: Our greatest security risks and how to address them". https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA421883.

- ↑ Lyu, M.R.; Lau, L.K.Y. (2000). "Firewall security: Policies, testing and performance evaluation". Proceedings 24th Annual International Computer Software and Applications Conference. COMPSAC2000. IEEE Comput. Soc. pp. 116–121. doi:10.1109/cmpsac.2000.884700. ISBN 0-7695-0792-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/cmpsac.2000.884700.

- ↑ "How the Lack of Data Standardization Impedes Data-Driven Healthcare", Data-Driven Healthcare (Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.): pp. 29, 2015-10-17, doi:10.1002/9781119205012.ch3, ISBN 978-1-119-20501-2, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781119205012.ch3, retrieved 2021-05-28

- ↑ Lent, Tom; Walsh, Bill (2009), "Rethinking Green Building Standards for Comprehensive Continuous Improvement", Common Ground, Consensus Building and Continual Improvement: International Standards and Sustainable Building (West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International): pp. 1–1–10, doi:10.1520/stp47516s, ISBN 978-0-8031-4507-8, http://dx.doi.org/10.1520/stp47516s, retrieved 2021-05-28

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cherdantseva Y. and Hilton J.: "Information Security and Information Assurance. The Discussion about the Meaning, Scope and Goals". In: Organizational, Legal, and Technological Dimensions of Information System Administrator. Almeida F., Portela, I. (eds.). IGI Global Publishing. (2013)

- ↑ ISO/IEC 27000:2018 (E). (2018). Information technology – Security techniques – Information security management systems – Overview and vocabulary. ISO/IEC.

- ↑ Committee on National Security Systems: National Information Assurance (IA) Glossary, CNSS Instruction No. 4009, 26 April 2010.

- ↑ ISACA. (2008). Glossary of terms, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.isaca.org/Knowledge-Center/Documents/Glossary/glossary.pdf

- ↑ Pipkin, D. (2000). Information security: Protecting the global enterprise. New York: Hewlett-Packard Company.

- ↑ B., McDermott, E., & Geer, D. (2001). Information security is information risk management. In Proceedings of the 2001 Workshop on New Security Paradigms NSPW ‘01, (pp. 97 – 104). ACM. doi:10.1145/508171.508187

- ↑ Anderson, J. M. (2003). "Why we need a new definition of information security". Computers & Security 22 (4): 308–313. doi:10.1016/S0167-4048(03)00407-3.

- ↑ Venter, H. S.; Eloff, J. H. P. (2003). "A taxonomy for information security technologies". Computers & Security 22 (4): 299–307. doi:10.1016/S0167-4048(03)00406-1.

- ↑ Gold, S (December 2004). "Threats looming beyond the perimeter". Information Security Technical Report 9 (4): 12–14. doi:10.1016/s1363-4127(04)00047-0. ISSN 1363-4127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1363-4127(04)00047-0.

- ↑ Parker, Donn B. (January 1993). "A Comprehensive List of Threats To Information". Information Systems Security 2 (2): 10–14. doi:10.1080/19393559308551348. ISSN 1065-898X. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19393559308551348.

- ↑ Sullivant, John (2016), "The Evolving Threat Environment", Building a Corporate Culture of Security (Elsevier): pp. 33–50, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-802019-7.00004-3, ISBN 978-0-12-802019-7, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-802019-7.00004-3, retrieved 2021-05-28