Biology:Uncoupling protein

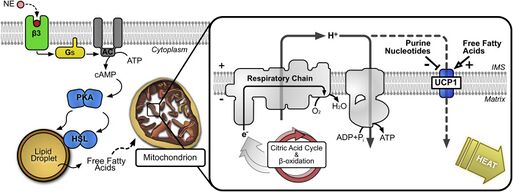

An uncoupling protein (UCP) is a mitochondrial inner membrane protein that is a regulated proton channel or transporter. An uncoupling protein is thus capable of dissipating the proton gradient generated by NADH-powered pumping of protons from the mitochondrial matrix to the mitochondrial intermembrane space. The energy lost in dissipating the proton gradient via UCPs is not used to do biochemical work. Instead, heat is generated. This is what links UCP to thermogenesis. However, not every type of UCPs are related to thermogenesis. Although UCP2 and UCP3 are closely related to UCP1, UCP2 and UCP3 do not affect thermoregulatory abilities of vertebrates.[1] UCPs are positioned in the same membrane as the ATP synthase, which is also a proton channel. The two proteins thus work in parallel with one generating heat and the other generating ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate, the last step in oxidative phosphorylation.[2] Mitochondria respiration is coupled to ATP synthesis (ADP phosphorylation), but is regulated by UCPs.[3][4] UCPs belong to the mitochondrial carrier (SLC25) family.[5][6]

Uncoupling proteins play a role in normal physiology, as in cold exposure or hibernation, because the energy is used to generate heat (see thermogenesis) instead of producing ATP. Some plants species use the heat generated by uncoupling proteins for special purposes. Eastern skunk cabbage, for example, keeps the temperature of its spikes as much as 20 °C higher than the environment, spreading odor and attracting insects that fertilize the flowers.[7] However, other substances, such as 2,4-dinitrophenol and carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone, also serve the same uncoupling function. Salicylic acid is also an uncoupling agent (chiefly in plants) and will decrease production of ATP and increase body temperature if taken in extreme excess.[8] Uncoupling proteins are increased by thyroid hormone, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and leptin.[9]

History

Scientists observed the thermogenic activity in brown adipose tissue, which eventually led to the discovery of UCP1, initially known as "Uncoupling Protein".[3][4] The brown tissue revealed elevated levels of mitochondria respiration and another respiration not coupled to ATP synthesis, which symbolized strong thermogenic activity.[3][4] UCP1 was the protein discovered responsible for activating a proton pathway that was not coupled to ADP phosphorylation (ordinarily done through ATP Synthase).[3]

In mammals

There are five UCP homologs known in mammals. While each of these performs unique functions, certain functions are performed by several of the homologs. The homologs are as follows:

- UCP1, also known as thermogenin or SLC25A7

- UCP2, also known as SLC25A8

- UCP3, also known as SLC25A9

- UCP4, also known as SLC25A27

- UCP5, also known as SLC25A14

Maintaining body temperature

The first uncoupling protein discovered, UCP1, was discovered in the brown adipose tissues of hibernators and small rodents, which provide non-shivering heat to these animals.[3][4] These brown adipose tissues are essential to maintaining the body temperature of small rodents, and studies with (UCP1)-knockout mice show that these tissues do not function correctly without functioning uncoupling proteins.[3][4] In fact, these studies revealed that cold-acclimation is not possible for these knockout mice, indicating that UCP1 is an essential driver of heat production in these brown adipose tissues.[10][11]

Elsewhere in the body, uncoupling protein activities are known to affect the temperature in micro-environments.[12][13] This is believed to affect other proteins' activity in these regions, though work is still required to determine the true consequences of uncoupling-induced temperature gradients within cells.[12]

The structure of human uncoupling protein 1 UCP1 has been solved by cryogenic-electron microscopy.[14] The structure has the typical fold of a member of the SLC25 family.[5][6] UCP1 is locked in a cytoplasmic-open state by guanosine triphosphate in a pH-dependent manner.[14]

Role in ATP concentrations

The effect of UCP2 and UCP3 on ATP concentrations varies depending on cell type.[12] For example, pancreatic beta cells experience a decrease in ATP concentration with increased activity of UCP2.[12] This is associated with cell degeneration, decreased insulin secretion, and type II diabetes.[12][15] Conversely, UCP2 in hippocampus cells and UCP3 in muscle cells stimulate production of mitochondria.[12][16] The larger number of mitochondria increases the combined concentration of ADP and ATP, actually resulting in a net increase in ATP concentration when these uncoupling proteins become coupled (i.e. the mechanism to allow proton leaking is inhibited).[12][16]

Maintaining concentration of reactive oxygen species

The entire list of functions of UCP2 and UCP3 is not known.[17] However, studies indicate that these proteins are involved in a negative-feedback loop limiting the concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS).[18] Current scientific consensus states that UCP2 and UCP3 perform proton transportation only when activation species are present.[19] Among these activators are fatty acids, ROS, and certain ROS byproducts that are also reactive.[18][19] Therefore, higher levels of ROS directly and indirectly cause increased activity of UCP2 and UCP3.[18] This, in turn, increases proton leak from the mitochondria, lowering the proton-motive force across mitochondrial membranes, activating the electron transport chain.[17][18][19] Limiting the proton motive force through this process results in a negative feedback loop that limits ROS production.[18] Especially, UCP2 decreases the transmembrane potential of mitochondria, thus decreasing the production of ROS. Thus, cancer cells may increase the production of UCP2 in mitochondria.[20] This theory is supported by independent studies which show increased ROS production in both UCP2 and UCP3 knockout mice.[19]

This process is important to human health, as high-concentrations of ROS are believed to be involved in the development of degenerative diseases.[19]

Functions in neurons

By detecting the associated mRNA, UCP2, UCP4, and UCP5 were shown to reside in neurons throughout the human central nervous system.[22] These proteins play key roles in neuronal function.[12] While many study findings remain controversial, several findings are widely accepted.[12]

For example, UCPs alter the free calcium concentrations in the neuron.[12] Mitochondria are a major site of calcium storage in neurons, and the storage capacity increases with potential across mitochondrial membranes.[12][23] Therefore, when the uncoupling proteins reduce potential across these membranes, calcium ions are released to the surrounding environment in the neuron.[12] Due to the high concentrations of mitochondria near axon terminals, this implies UCPs play a role in regulating calcium concentrations in this region.[12] Considering calcium ions play a large role in neurotransmission, scientists predict that these UCPs directly affect neurotransmission.[12]

As discussed above, neurons in the hippocampus experience increased concentrations of ATP in the presence of these uncoupling proteins.[12][16] This leads scientists to hypothesize that UCPs improve synaptic plasticity and transmission.[12]

See also

- Uncoupling agent

References

- ↑ "Molecular evolution of uncoupling proteins and implications for brain function". Neuroscience Letters 696: 140–145. March 2019. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2018.12.027. PMID 30582970.

- ↑ "Uncoupling proteins: current status and therapeutic prospects". EMBO Reports 6 (10): 917–21. October 2005. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400532. PMID 16179945.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "The biology of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins". Diabetes 53 (suppl 1): S130-5. February 2004. doi:10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.S130. PMID 14749278.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Nicholls, D.G. (2021). "Mitochondrial proton leaks and uncoupling proteins". Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1862 (7): 148428. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2021.148428. PMID 33798544. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33798544.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ruprecht, J.J.; Kunji, E.R.S. (2020). "The SLC25 Mitochondrial Carrier Family: Structure and Mechanism". Trends Biochem. Sci. 45 (3): 244–258. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2019.11.001. PMID 31787485.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kunji, E.R.S.; King, M.S.; Ruprecht, J.J.; Thangaratnarajah, C. (2020). "The SLC25 Carrier Family: Important Transport Proteins in Mitochondrial Physiology and Pathology". Physiology (Bethesda) 35 (5): 302–327. doi:10.1152/physiol.00009.2020. PMID 32783608.

- ↑ Garrett, Reginald H.; Grisham, Charles M. (2013). Biochemistry (Fifth Edition, International ed.). China: Mary Finch. pp. 668. ISBN 978-1-133-10879-5.

- ↑ "California Poison Control System: Salicylates". http://www.calpoison.org/hcp/2009/callusvol7no4.htm.

- ↑ "Uncoupling protein-3 is a mediator of thermogenesis regulated by thyroid hormone, beta3-adrenergic agonists, and leptin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (39): 24129–32. September 1997. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.39.24129. PMID 9305858.

- ↑ "Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins in human physiology and disease". Minerva Medica 93 (1): 41–57. February 2002. PMID 11850613.

- ↑ "UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality". Cell Metabolism 9 (2): 203–9. February 2009. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.014. PMID 19187776.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 "Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins in the CNS: in support of function and survival". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 6 (11): 829–40. November 2005. doi:10.1038/nrn1767. PMID 16224498.

- ↑ "Brain uncoupling protein 2: uncoupled neuronal mitochondria predict thermal synapses in homeostatic centers". The Journal of Neuroscience 19 (23): 10417–27. December 1999. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10417.1999. PMID 10575039.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Jones, S.A.; Gogoi, P.; Ruprecht, J.J.; King, M.S.; Lee, Y.; Zogg, T.; Pardon, E.; Chand, D. et al. (2023). "Structural basis of purine nucleotide inhibition of human uncoupling protein 1". Sci Adv 9 (22): eadh4251. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adh4251. PMID 37256948. Bibcode: 2023SciA....9H4251J.

- ↑ "Uncoupling protein-2 negatively regulates insulin secretion and is a major link between obesity, beta cell dysfunction, and type 2 diabetes". Cell 105 (6): 745–55. June 2001. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00378-6. PMID 11440717.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Uncoupling protein 2 prevents neuronal death including that occurring during seizures: a mechanism for preconditioning". Endocrinology 144 (11): 5014–21. November 2003. doi:10.1210/en.2003-0667. PMID 12960023.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Mitochondrial proton and electron leaks". Essays in Biochemistry 47: 53–67. 2010-06-14. doi:10.1042/bse0470053. PMID 20533900.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 "Uncoupling proteins and the control of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production". Free Radical Biology & Medicine 51 (6): 1106–15. September 2011. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.022. PMID 21762777.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 "Physiological functions of the mitochondrial uncoupling proteins UCP2 and UCP3". Cell Metabolism 2 (2): 85–93. August 2005. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.002. PMID 16098826.

- ↑ "Uncoupling protein 2 and metabolic diseases". Mitochondrion 34: 135–140. May 2017. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2017.03.005. PMID 28351676.

- ↑ Crichton, P.G.; Lee, Y.; Kunji, E.R.S. (2017). "The molecular features of uncoupling protein 1 support a conventional mitochondrial carrier-like mechanism". Biochimie 134: 35–50. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2016.12.016. PMID 28057583.

- ↑ "Uncoupling protein 2 in the brain: distribution and function". Biochemical Society Transactions 29 (Pt 6): 812–7. November 2001. doi:10.1042/bst0290812. PMID 11709080.

- ↑ "Mitochondrial membrane potential and neuronal glutamate excitotoxicity: mortality and millivolts". Trends in Neurosciences 23 (4): 166–74. April 2000. doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01534-9. PMID 10717676.

|