Biology:ATP synthase

| ATP Synthase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

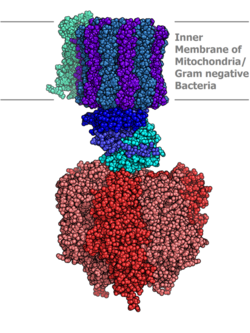

Molecular model of ATP synthase determined by X-ray crystallography. Stator is not shown here. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 7.1.2.2 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 9000-83-3 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

ATP synthase is an enzyme that catalyzes the formation of the energy storage molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP) using adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi). ATP synthase is a molecular machine. The overall reaction catalyzed by ATP synthase is:

- ADP + Pi + 2H+out ⇌ ATP + H2O + 2H+in

ATP synthase lies across a cellular membrane and forms an aperture that protons can cross from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration, imparting energy for the synthesis of ATP. This electrochemical gradient is generated by the electron transport chain and allows cells to store energy in ATP for later use. In prokaryotic cells ATP synthase lies across the plasma membrane, while in eukaryotic cells it lies across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Organisms capable of photosynthesis also have ATP synthase across the thylakoid membrane, which in plants is located in the chloroplast and in cyanobacteria is located in the cytoplasm.

Eukaryotic ATP synthases are F-ATPases, running "in reverse" for an ATPase. This article deals mainly with this type. An F-ATPase consists of two main subunits, FO and F1, which has a rotational motor mechanism allowing for ATP production.[1][2]

Nomenclature

The F1 fraction derives its name from the term "Fraction 1" and FO (written as a subscript letter "o", not "zero") derives its name from being the binding fraction for oligomycin, a type of naturally derived antibiotic that is able to inhibit the FO unit of ATP synthase.[3][4] These functional regions consist of different protein subunits — refer to tables. This enzyme is used in synthesis of ATP through aerobic respiration.

Structure and function

Located within the thylakoid membrane and the inner mitochondrial membrane, ATP synthase consists of two regions FO and F1. FO causes rotation of F1 and is made of c-ring and subunits a, two b, F6. F1 is made of α, β, γ, and δ subunits. F1 has a water-soluble part that can hydrolyze ATP. FO on the other hand has mainly hydrophobic regions. FO F1 creates a pathway for protons movement across the membrane.[7]

F1 region

The F1 portion of ATP synthase is hydrophilic and responsible for hydrolyzing ATP. The F1 unit protrudes into the mitochondrial matrix space. Subunits α and β make a hexamer with 6 binding sites. Three of them are catalytically inactive and they bind ADP.

Three other subunits catalyze the ATP synthesis. The other F1 subunits γ, δ, and ε are a part of a rotational motor mechanism (rotor/axle). The γ subunit allows β to go through conformational changes (i.e., closed, half open, and open states) that allow for ATP to be bound and released once synthesized. The F1 particle is large and can be seen in the transmission electron microscope by negative staining.[8] These are particles of 9 nm diameter that pepper the inner mitochondrial membrane.

| Subunit | Human Gene | Note |

|---|---|---|

| alpha | ATP5A1, ATPAF2 | |

| beta | ATP5B, ATPAF1 | |

| gamma | ATP5C1 | |

| delta | ATP5D | Mitochondrial "delta" is bacterial/chloroplastic epsilon. |

| epsilon | ATP5E | Unique to mitochondria. |

| OSCP | ATP5O | Called "delta" in bacterial and chloroplastic versions. |

FO region

FO is a water insoluble protein with eight subunits and a transmembrane ring. The ring has a tetrameric shape with a helix-loop-helix protein that goes through conformational changes when protonated and deprotonated, pushing neighboring subunits to rotate, causing the spinning of FO which then also affects conformation of F1, resulting in switching of states of alpha and beta subunits. The FO region of ATP synthase is a proton pore that is embedded in the mitochondrial membrane. It consists of three main subunits, a, b, and c. Six c subunits make up the rotor ring, and subunit b makes up a stalk connecting to F1 OSCP that prevents the αβ hexamer from rotating. Subunit a connects b to the c ring.[11] Humans have six additional subunits, d, e, f, g, F6, and 8 (or A6L). This part of the enzyme is located in the mitochondrial inner membrane and couples proton translocation to the rotation that causes ATP synthesis in the F1 region.

In eukaryotes, mitochondrial FO forms membrane-bending dimers. These dimers self-arrange into long rows at the end of the cristae, possibly the first step of cristae formation.[12] An atomic model for the dimeric yeast FO region was determined by cryo-EM at an overall resolution of 3.6 Å.[13]

| Subunit | Human Gene |

|---|---|

| a | MT-ATP6 |

| b | ATP5F1 |

| c | ATP5G1, ATP5G2, ATP5G3 |

Binding model

In the 1960s through the 1970s, Paul Boyer, a UCLA Professor, developed the binding change, or flip-flop, mechanism theory, which postulated that ATP synthesis is dependent on a conformational change in ATP synthase generated by rotation of the gamma subunit. The research group of John E. Walker, then at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, crystallized the F1 catalytic-domain of ATP synthase. The structure, at the time the largest asymmetric protein structure known, indicated that Boyer's rotary-catalysis model was, in essence, correct. For elucidating this, Boyer and Walker shared half of the 1997 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

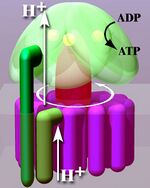

The crystal structure of the F1 showed alternating alpha and beta subunits (3 of each), arranged like segments of an orange around a rotating asymmetrical gamma subunit. According to the current model of ATP synthesis (known as the alternating catalytic model), the transmembrane potential created by (H+) proton cations supplied by the electron transport chain, drives the (H+) proton cations from the intermembrane space through the membrane via the FO region of ATP synthase. A portion of the FO (the ring of c-subunits) rotates as the protons pass through the membrane. The c-ring is tightly attached to the asymmetric central stalk (consisting primarily of the gamma subunit), causing it to rotate within the alpha3beta3 of F1 causing the 3 catalytic nucleotide binding sites to go through a series of conformational changes that lead to ATP synthesis. The major F1 subunits are prevented from rotating in sympathy with the central stalk rotor by a peripheral stalk that joins the alpha3beta3 to the non-rotating portion of FO. The structure of the intact ATP synthase is currently known at low-resolution from electron cryo-microscopy (cryo-EM) studies of the complex. The cryo-EM model of ATP synthase suggests that the peripheral stalk is a flexible structure that wraps around the complex as it joins F1 to FO. Under the right conditions, the enzyme reaction can also be carried out in reverse, with ATP hydrolysis driving proton pumping across the membrane.

The binding change mechanism involves the active site of a β subunit's cycling between three states.[14] In the "loose" state, ADP and phosphate enter the active site; in the adjacent diagram, this is shown in pink. The enzyme then undergoes a change in shape and forces these molecules together, with the active site in the resulting "tight" state (shown in red) binding the newly produced ATP molecule with very high affinity. Finally, the active site cycles back to the open state (orange), releasing ATP and binding more ADP and phosphate, ready for the next cycle of ATP production.[15]

Physiological role

Like other enzymes, the activity of F1FO ATP synthase is reversible. Large-enough quantities of ATP cause it to create a transmembrane proton gradient, this is used by fermenting bacteria that do not have an electron transport chain, but rather hydrolyze ATP to make a proton gradient, which they use to drive flagella and the transport of nutrients into the cell.

In respiring bacteria under physiological conditions, ATP synthase, in general, runs in the opposite direction, creating ATP while using the proton motive force created by the electron transport chain as a source of energy. The overall process of creating energy in this fashion is termed oxidative phosphorylation. The same process takes place in the mitochondria, where ATP synthase is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane and the F1-part projects into the mitochondrial matrix. By pumping proton cations into the matrix, the ATP-synthase converts ADP into ATP.

Evolution

The evolution of ATP synthase is thought to have been modular whereby two functionally independent subunits became associated and gained new functionality.[16][17] This association appears to have occurred early in evolutionary history, because essentially the same structure and activity of ATP synthase enzymes are present in all kingdoms of life.[16] The F-ATP synthase displays high functional and mechanistic similarity to the V-ATPase.[18] However, whereas the F-ATP synthase generates ATP by utilising a proton gradient, the V-ATPase generates a proton gradient at the expense of ATP, generating pH values of as low as 1.[19]

The F1 region also shows significant similarity to hexameric DNA helicases (especially the Rho factor), and the entire enzyme region shows some similarity to H+-powered T3SS or flagellar motor complexes.[18][20][21] The α3β3 hexamer of the F1 region shows significant structural similarity to hexameric DNA helicases; both form a ring with 3-fold rotational symmetry with a central pore. Both have roles dependent on the relative rotation of a macromolecule within the pore; the DNA helicases use the helical shape of DNA to drive their motion along the DNA molecule and to detect supercoiling, whereas the α3β3 hexamer uses the conformational changes through the rotation of the γ subunit to drive an enzymatic reaction.[22]

The H+ motor of the FO particle shows great functional similarity to the H+ motors that drive flagella.[18] Both feature a ring of many small alpha-helical proteins that rotate relative to nearby stationary proteins, using a H+ potential gradient as an energy source. This link is tenuous, however, as the overall structure of flagellar motors is far more complex than that of the FO particle and the ring with about 30 rotating proteins is far larger than the 10, 11, or 14 helical proteins in the FO complex. More recent structural data do however show that the ring and the stalk are structurally similar to the F1 particle.[21]

File:ATP synthesis - ATP synthase rotation.ogv The modular evolution theory for the origin of ATP synthase suggests that two subunits with independent function, a DNA helicase with ATPase activity and a H+ motor, were able to bind, and the rotation of the motor drove the ATPase activity of the helicase in reverse.[16][22] This complex then evolved greater efficiency and eventually developed into today's intricate ATP synthases. Alternatively, the DNA helicase/H+ motor complex may have had H+ pump activity with the ATPase activity of the helicase driving the H+ motor in reverse.[16] This may have evolved to carry out the reverse reaction and act as an ATP synthase.[17][23][24]

Inhibitors

A variety of natural and synthetic inhibitors of ATP synthase have been discovered.[25] These have been used to probe the structure and mechanism of ATP synthase. Some may be of therapeutic use. There are several classes of ATP synthase inhibitors, including peptide inhibitors, polyphenolic phytochemicals, polyketides, organotin compounds, polyenic α-pyrone derivatives, cationic inhibitors, substrate analogs, amino acid modifiers, and other miscellaneous chemicals.[25] Some of the most commonly used ATP synthase inhibitors are oligomycin and DCCD.

In different organisms

Bacteria

E. coli ATP synthase is the simplest known form of ATP synthase, with 8 different subunit types.[11]

Bacterial F-ATPases can occasionally operate in reverse, turning them into an ATPase.[26] Some bacteria have no F-ATPase, using an A/V-type ATPase bidirectionally.[9]

Yeast

Yeast ATP synthase is one of the best-studied eukaryotic ATP synthases; and five F1, eight FO subunits, and seven associated proteins have been identified.[7] Most of these proteins have homologues in other eukaryotes.[27][28][29][30]

Plant

In plants, ATP synthase is also present in chloroplasts (CF1FO-ATP synthase). The enzyme is integrated into thylakoid membrane; the CF1-part sticks into stroma, where dark reactions of photosynthesis (also called the light-independent reactions or the Calvin cycle) and ATP synthesis take place. The overall structure and the catalytic mechanism of the chloroplast ATP synthase are almost the same as those of the bacterial enzyme. However, in chloroplasts, the proton motive force is generated not by respiratory electron transport chain but by primary photosynthetic proteins. The synthase has a 40-aa insert in the gamma-subunit to inhibit wasteful activity when dark.[31]

Mammal

The ATP synthase isolated from bovine (Bos taurus) heart mitochondria is, in terms of biochemistry and structure, the best-characterized ATP synthase. Beef heart is used as a source for the enzyme because of the high concentration of mitochondria in cardiac muscle. Their genes have close homology to human ATP synthases.[32][33][34]

Human genes that encode components of ATP synthases:

- ATP5A1

- ATP5B

- ATP5C1, ATP5D, ATP5E, ATP5F1, ATP5G1, ATP5G2, ATP5G3, ATP5H, ATP5I, ATP5J, ATP5J2, ATP5L, ATP5O

- MT-ATP6, MT-ATP8

Other eukaryotes

Eukaryotes belonging to some divergent lineages have very special organizations of the ATP synthase. A euglenozoa ATP synthase forms a dimer with a boomerang-shaped F1 head like other mitochondrial ATP synthases, but the FO subcomplex has many unique subunits. It uses cardiolipin. The inhibitory IF1 also binds differently, in a way shared with trypanosomatida.[35]

Archaea

Archaea do not generally have an F-ATPase. Instead, they synthesize ATP using the A-ATPase/synthase, a rotary machine structurally similar to the V-ATPase but mainly functioning as an ATP synthase.[26] Like the bacteria F-ATPase, it is believed to also function as an ATPase.[9]

LUCA and earlier

F-ATPase gene linkage and gene order are widely conserved across ancient prokaryote lineages, implying that this system already existed at a date before the last universal common ancestor, the LUCA.[36]

See also

- ATP10 protein required for the assembly of the FO sector of the mitochondrial ATPase complex.

- Chloroplast

- Electron transfer chain

- Flavoprotein

- Mitochondrion

- Oxidative phosphorylation

- P-ATPase

- Proton pump

- Rotating locomotion in living systems

- Transmembrane ATPase

- V-ATPase

References

- ↑ "Rotation and structure of FoF1-ATP synthase". Journal of Biochemistry 149 (6): 655–664. June 2011. doi:10.1093/jb/mvr049. PMID 21524994.

- ↑ "ATP synthase". Annual Review of Biochemistry 84: 631–657. June 2015. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034124. PMID 25839341.

- ↑ "Partial resolution of the enzymes catalyzing oxidative phosphorylation. 8. Properties of a factor conferring oligomycin sensitivity on mitochondrial adenosine triphosphatase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 241 (10): 2461–2466. May 1966. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)96640-8. PMID 4223640.

- ↑ "A PLANT BIOCHEMIST'S VIEW OF H+-ATPases AND ATP SYNTHASES". The Journal of Experimental Biology 172 (Pt 1): 431–441. November 1992. doi:10.1242/jeb.172.1.431. PMID 9874753.

- ↑ PDB: 5ARA; "Structure and conformational states of the bovine mitochondrial ATP synthase by cryo-EM". eLife 4: e10180. October 2015. doi:10.7554/eLife.10180. PMID 26439008.

- ↑ Goodsell, David (December 2005). "ATP Synthase". Molecule of the Month. doi:10.2210/rcsb_pdb/mom_2005_12. https://pdb101.rcsb.org/motm/72.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Organisation of the yeast ATP synthase F(0):a study based on cysteine mutants, thiol modification and cross-linking reagents". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1458 (2–3): 443–456. May 2000. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00093-1. PMID 10838057.

- ↑ "A macromolecular repeating unit of mitochondrial structure and function. Correlated electron microscopic and biochemical studies of isolated mitochondria and submitochondrial particles of beef heart muscle". The Journal of Cell Biology 22 (1): 63–100. July 1964. doi:10.1083/jcb.22.1.63. PMID 14195622.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Rotary ATPases--dynamic molecular machines". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 25: 40–48. April 2014. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2013.11.013. PMID 24878343.

- ↑ PDB: 1VZS; "Solution structure of subunit F(6) from the peripheral stalk region of ATP synthase from bovine heart mitochondria". Journal of Molecular Biology 342 (2): 593–603. September 2004. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.013. PMID 15327958.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Role of Charged Residues in the Catalytic Sites of Escherichia coli ATP Synthase". Journal of Amino Acids 2011: 785741. 2011. doi:10.4061/2011/785741. PMID 22312470.

- ↑ "Dimers of mitochondrial ATP synthase induce membrane curvature and self-assemble into rows". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116 (10): 4250–4255. March 2019. doi:10.1073/pnas.1816556116. PMID 30760595. Bibcode: 2019PNAS..116.4250B.

- ↑ "Atomic model for the dimeric FO region of mitochondrial ATP synthase". Science 358 (6365): 936–940. November 2017. doi:10.1126/science.aao4815. PMID 29074581. Bibcode: 2017Sci...358..936G.

- ↑ "Catalytic site cooperativity of beef heart mitochondrial F1 adenosine triphosphatase. Correlations of initial velocity, bound intermediate, and oxygen exchange measurements with an alternating three-site model". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 257 (20): 12030–12038. October 1982. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)33672-X. PMID 6214554.

- ↑ "The rotary mechanism of the ATP synthase". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 476 (1): 43–50. August 2008. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2008.05.004. PMID 18515057.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "Rotary DNA motors". Biophysical Journal 69 (6): 2256–2267. December 1995. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80096-2. PMID 8599633. Bibcode: 1995BpJ....69.2256D.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Crofts, Antony. "Lecture 10:ATP synthase". Life Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. http://www.life.illinois.edu/crofts/bioph354/lect10.html.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "ATP Synthase". InterPro Database. http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/potm/2005_12/Page2.htm.

- ↑ "The V-type H+ ATPase: molecular structure and function, physiological roles and regulation". The Journal of Experimental Biology 209 (Pt 4): 577–589. February 2006. doi:10.1242/jeb.02014. PMID 16449553.

- ↑ "Structure of the Rho transcription terminator: mechanism of mRNA recognition and helicase loading". Cell 114 (1): 135–146. July 2003. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00512-9. PMID 12859904.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Insight into the flagella type III export revealed by the complex structure of the type III ATPase and its regulator". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113 (13): 3633–3638. March 2016. doi:10.1073/pnas.1524025113. PMID 26984495. Bibcode: 2016PNAS..113.3633I.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Ectopic beta-chain of ATP synthase is an apolipoprotein A-I receptor in hepatic HDL endocytosis". Nature 421 (6918): 75–79. January 2003. doi:10.1038/nature01250. PMID 12511957. Bibcode: 2003Natur.421...75M.

- ↑ "Gene duplication as a means for altering H+/ATP ratios during the evolution of FOF1 ATPases and synthases". FEBS Letters 259 (2): 227–229. January 1990. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(90)80014-a. PMID 2136729.

- ↑ "The evolution of A-, F-, and V-type ATP synthases and ATPases: reversals in function and changes in the H+/ATP coupling ratio". FEBS Letters 576 (1–2): 1–4. October 2004. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.065. PMID 15473999.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "ATP synthase and the actions of inhibitors utilized to study its roles in human health, disease, and other scientific areas". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 72 (4): 590–641, Table of Contents. December 2008. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00016-08. PMID 19052322.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Rotary ATPases: A New Twist to an Ancient Machine". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 41 (1): 106–116. January 2016. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2015.10.006. PMID 26671611.

- ↑ "Insights into ATP synthase assembly and function through the molecular genetic manipulation of subunits of the yeast mitochondrial enzyme complex". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1458 (2–3): 428–442. May 2000. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00092-X. PMID 10838056.

- ↑ "Novel features of the rotary catalytic mechanism revealed in the structure of yeast F1 ATPase". The EMBO Journal 25 (22): 5433–5442. November 2006. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601410. PMID 17082766.

- ↑ "Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase". Science 286 (5445): 1700–1705. November 1999. doi:10.1126/science.286.5445.1700. PMID 10576729.

- ↑ "The purification and characterization of ATP synthase complexes from the mitochondria of four fungal species". The Biochemical Journal 468 (1): 167–175. May 2015. doi:10.1042/BJ20150197. PMID 25759169.

- ↑ "Structure, mechanism, and regulation of the chloroplast ATP synthase". Science 360 (6389): eaat4318. May 2018. doi:10.1126/science.aat4318. PMID 29748256.

- ↑ "Structure at 2.8 A resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria". Nature 370 (6491): 621–628. August 1994. doi:10.1038/370621a0. PMID 8065448. Bibcode: 1994Natur.370..621A.

- ↑ "The structure of the central stalk in bovine F(1)-ATPase at 2.4 A resolution". Nature Structural Biology 7 (11): 1055–1061. November 2000. doi:10.1038/80981. PMID 11062563.

- ↑ "Structure of bovine mitochondrial F(1)-ATPase with nucleotide bound to all three catalytic sites: implications for the mechanism of rotary catalysis". Cell 106 (3): 331–341. August 2001. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00452-4. PMID 11509182.

- ↑ "Structure of a mitochondrial ATP synthase with bound native cardiolipin". eLife 8: e51179. November 2019. doi:10.7554/eLife.51179. PMID 31738165.

- "Different from the rest". December 24, 2019. https://elifesciences.org/digests/51179/different-from-the-rest.

- ↑ "Flagellar export apparatus and ATP synthetase: Homology evidenced by synteny predating the Last Universal Common Ancestor". BioEssays 43 (7): e2100004. July 2021. doi:10.1002/bies.202100004. PMID 33998015.

Further reading

- Nick Lane: The Vital Question: Energy, Evolution, and the Origins of Complex Life, Ww Norton, 2015-07-20, ISBN 978-0393088816 (Link points to Figure 10 showing model of ATP synthase)

External links

- Boris A. Feniouk: "ATP synthase — a splendid molecular machine"

- Well illustrated ATP synthase lecture by Antony Crofts of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign.

- Proton and Sodium translocating F-type, V-type and A-type ATPases in OPM database

- The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1997 to Paul D. Boyer and John E. Walker for the enzymatic mechanism of synthesis of ATP; and to Jens C. Skou, for discovery of an ion-transporting enzyme, Na+, K+-ATPase.

- Harvard Multimedia Production Site — Videos – ATP synthesis animation

- David Goodsell: "ATP Synthase- Molecule of the Month"

|