Chemistry:Mercury sulfide

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Mercury sulfide

| |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2025 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| HgS | |

| Molar mass | 232.66 g/mol |

| Density | 8.10 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 580 °C (1,076 °F; 853 K) decomposes |

| insoluble | |

| Band gap | 2.1 eV (direct, α-HgS) [1] |

| −55.4·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

w=2.905, e=3.256, bire=0.3510 (α-HgS) [2] |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S |

78 J·mol−1·K−1[3] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−58 kJ·mol−1[3] |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | Fisher Scientific |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

| H300, H310, H317, H330, H373, H410 | |

| P261, P272, P280, P302+352, P321, P333+313, P363, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Mercury oxide mercury selenide mercury telluride |

Other cations

|

Zinc sulfide cadmium sulfide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Mercury sulfide, or mercury(II) sulfide is a chemical compound composed of the chemical elements mercury and sulfur. It is represented by the chemical formula HgS. It is virtually insoluble in water.[4]

Crystal structure

HgS is dimorphic with two crystal forms:

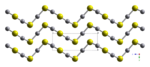

- red cinnabar (α-HgS, trigonal, hP6, P3221) is the form in which mercury is most commonly found in nature. Cinnabar has rhombohedral crystal system. Crystals of red are optically active. This is caused by the Hg-S helices in the structure.[5]

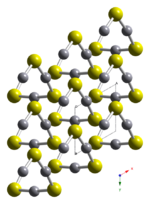

- black metacinnabar (β-HgS) is less common in nature and adopts the zinc blende crystal structure (T2d-F43m).

Preparation and chemistry

β-HgS precipitates as a black solid when Hg(II) salts are treated with H2S. The reaction is conveniently conducted with an acetic acid solution of mercury(II) acetate. With gentle heating of the slurry, the black polymorph converts to the red form.[6] β-HgS is unreactive to all but concentrated acids.[4]

Mercury is produced from the cinnabar ore by roasting in air and condensing the vapour.[4]

- HgS → Hg + S

Uses

When α-HgS is used as a red pigment, it is known as cinnabar. The tendency of cinnabar to darken has been ascribed to conversion from red α-HgS to black β-HgS. However β-HgS was not detected at excavations in Pompeii, where originally red walls darkened, and was attributed to the formation of Hg-Cl compounds (e.g., corderoite, calomel, and terlinguaite) and calcium sulfate, gypsum.[7]

As the mercury cell as used in the chlor-alkali industry (Castner–Kellner process) is being phased out over concerns over mercury emissions, the metallic mercury from these setups is converted into mercury sulfide for underground storage.

With a band gap of 2.1 eV and its stability, it is possible to be used as photoelectrochemical cell.[8]

Neutralization with sulfur has been suggested to clean mercury spills, but the reaction does not proceed rapidly and completely enough for emergencies.[9]

See also

- Mercury poisoning

- Mercury(I) sulfide (mercurous sulfide, Hg2S), hypothetical

References

- ↑ L. I. Berger, Semiconductor Materials (1997) CRC Press ISBN:0-8493-8912-7

- ↑ Webminerals

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed.. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A22. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon Press. p. 1406. ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=OezvAAAAMAAJ&q=0-08-022057-6&dq=0-08-022057-6&source=bl&ots=m4tIRxdwSk&sig=XQTTjw5EN9n5z62JB3d0vaUEn0Y&hl=en&sa=X&ei=UoAWUN7-EM6ziQfyxIDoCQ&ved=0CD8Q6AEwBA.

- ↑ A. M. Glazer, K. Stadnicka (1986). "On the origin of optical activity in crystal structures". J. Appl. Crystallogr. 19 (2): 108–122. doi:10.1107/S0021889886089823. Bibcode: 1986JApCr..19..108G.

- ↑ Newell, Lyman C.; Maxson, R. N.; Filson, M. H. (1939). "Red Mercuric Sulfide". Inorganic Syntheses. 1. pp. 19–20. doi:10.1002/9780470132326.ch7. ISBN 9780470132326.

- ↑ Cotte, M; Susini J; Metrich N; Moscato A; Gratziu C; Bertagnini A; Pagano M (2006). "Blackening of Pompeian Cinnabar Paintings: X-ray Microspectroscopy Analysis". Anal. Chem. 78 (21): 7484–7492. doi:10.1021/ac0612224. PMID 17073416.

- ↑ Davidson, R. S.; Willsher, C. J. (March 1979). "Mercury(II) sulphide: a photo-stable semiconductor" (in en). Nature 278 (5701): 238–239. doi:10.1038/278238a0. ISSN 1476-4687. Bibcode: 1979Natur.278..238D. https://www.nature.com/articles/278238a0.

- ↑ Hegedüs, Kristof (20 Dec 2014). "How NOT to clean up mercury....". Tumblr. https://labphoto.tumblr.com/post/105712717764/how-not-to-clean-up-mercury-at-us-in-secondary.

|