Duality (mathematics)

In mathematics, a duality translates concepts, theorems or mathematical structures into other concepts, theorems or structures in a one-to-one fashion, often (but not always) by means of an involution operation: if the dual of A is B, then the dual of B is A. Such involutions sometimes have fixed points, so that the dual of A is A itself. For example, Desargues' theorem is self-dual in this sense under the standard duality in projective geometry.

In mathematical contexts, duality has numerous meanings.[1] It has been described as "a very pervasive and important concept in (modern) mathematics"[2] and "an important general theme that has manifestations in almost every area of mathematics".[3]

Many mathematical dualities between objects of two types correspond to pairings, bilinear functions from an object of one type and another object of the second type to some family of scalars. For instance, linear algebra duality corresponds in this way to bilinear maps from pairs of vector spaces to scalars, the duality between distributions and the associated test functions corresponds to the pairing in which one integrates a distribution against a test function, and Poincaré duality corresponds similarly to intersection number, viewed as a pairing between submanifolds of a given manifold.[4]

From a category theory viewpoint, duality can also be seen as a functor, at least in the realm of vector spaces. This functor assigns to each space its dual space, and the pullback construction assigns to each arrow f: V → W its dual f∗: W∗ → V∗.

Introductory examples

In the words of Michael Atiyah,

Duality in mathematics is not a theorem, but a "principle".[5]

The following list of examples shows the common features of many dualities, but also indicates that the precise meaning of duality may vary from case to case.

Complement of a subset

A simple, maybe the most simple, duality arises from considering subsets of a fixed set S. To any subset A ⊆ S, the complement Ac[6] consists of all those elements in S that are not contained in A. It is again a subset of S. Taking the complement has the following properties:

- Applying it twice gives back the original set, i.e., (Ac)c = A. This is referred to by saying that the operation of taking the complement is an involution.

- An inclusion of sets A ⊆ B is turned into an inclusion in the opposite direction Bc ⊆ Ac.

- Given two subsets A and B of S, A is contained in Bc if and only if B is contained in Ac.

This duality appears in topology as a duality between open and closed subsets of some fixed topological space X: a subset U of X is closed if and only if its complement in X is open. Because of this, many theorems about closed sets are dual to theorems about open sets. For example, any union of open sets is open, so dually, any intersection of closed sets is closed. The interior of a set is the largest open set contained in it, and the closure of the set is the smallest closed set that contains it. Because of the duality, the complement of the interior of any set U is equal to the closure of the complement of U.

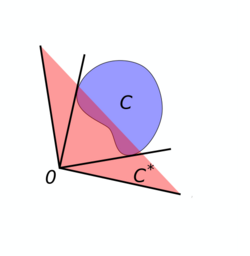

Dual cone

A duality in geometry is provided by the dual cone construction. Given a set of points in the plane (or more generally points in ), the dual cone is defined as the set consisting of those points satisfying for all points in , as illustrated in the diagram. Unlike for the complement of sets mentioned above, it is not in general true that applying the dual cone construction twice gives back the original set . Instead, is the smallest cone[7] containing which may be bigger than . Therefore this duality is weaker than the one above, in that

- Applying the operation twice gives back a possibly bigger set: for all , is contained in . (For some , namely the cones, the two are actually equal.)

The other two properties carry over without change:

- It is still true that an inclusion is turned into an inclusion in the opposite direction ().

- Given two subsets and of the plane, is contained in if and only if is contained in .

Dual vector space

A very important example of a duality arises in linear algebra by associating to any vector space V its dual vector space V*. Its elements are the linear functionals , where K is the field over which V is defined. The three properties of the dual cone carry over to this type of duality by replacing subsets of by vector space and inclusions of such subsets by linear maps. That is:

- Applying the operation of taking the dual vector space twice gives another vector space V**. There is always a map V → V**. For some V, namely precisely the finite-dimensional vector spaces, this map is an isomorphism.

- A linear map V → W gives rise to a map in the opposite direction (W* → V*).

- Given two vector spaces V and W, the maps from V to W* correspond to the maps from W to V*.

A particular feature of this duality is that V and V* are isomorphic for certain objects, namely finite-dimensional vector spaces. However, this is in a sense a lucky coincidence, for giving such an isomorphism requires a certain choice, for example the choice of a basis of V. This is also true in the case if V is a Hilbert space, via the Riesz representation theorem.

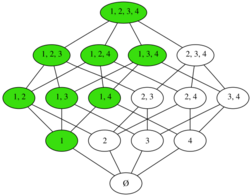

Galois theory

In all the dualities discussed before, the dual of an object is of the same kind as the object itself. For example, the dual of a vector space is again a vector space. Many duality statements are not of this kind. Instead, such dualities reveal a close relation between objects of seemingly different nature. One example of such a more general duality is from Galois theory. For a fixed Galois extension K / F, one may associate the Galois group Gal(K/E) to any intermediate field E (i.e., F ⊆ E ⊆ K). This group is a subgroup of the Galois group G = Gal(K/F). Conversely, to any such subgroup H ⊆ G there is the fixed field KH consisting of elements fixed by the elements in H.

Compared to the above, this duality has the following features:

- An extension F ⊆ F′ of intermediate fields gives rise to an inclusion of Galois groups in the opposite direction: Gal(K/F′) ⊆ Gal(K/F).

- Associating Gal(K/E) to E and KH to H are inverse to each other. This is the content of the fundamental theorem of Galois theory.

Order-reversing dualities

Given a poset P = (X, ≤) (short for partially ordered set; i.e., a set that has a notion of ordering but in which two elements cannot necessarily be placed in order relative to each other), the dual poset Pd = (X, ≥) comprises the same ground set but the converse relation. Familiar examples of dual partial orders include

- the subset and superset relations ⊂ and ⊃ on any collection of sets, such as the subsets of a fixed set S. This gives rise to the first example of a duality mentioned above.

- the divides and multiple-of relations on the integers.

- the descendant-of and ancestor-of relations on the set of humans.

A duality transform is an involutive antiautomorphism f of a partially ordered set S, that is, an order-reversing involution f : S → S.[8][9] In several important cases these simple properties determine the transform uniquely up to some simple symmetries. For example, if f1, f2 are two duality transforms then their composition is an order automorphism of S; thus, any two duality transforms differ only by an order automorphism. For example, all order automorphisms of a power set S = 2R are induced by permutations of R.

A concept defined for a partial order P will correspond to a dual concept on the dual poset Pd. For instance, a minimal element of P will be a maximal element of Pd: minimality and maximality are dual concepts in order theory. Other pairs of dual concepts are upper and lower bounds, lower sets and upper sets, and ideals and filters.

In topology, open sets and closed sets are dual concepts: the complement of an open set is closed, and vice versa. In matroid theory, the family of sets complementary to the independent sets of a given matroid themselves form another matroid, called the dual matroid.

Dimension-reversing dualities

There are many distinct but interrelated dualities in which geometric or topological objects correspond to other objects of the same type, but with a reversal of the dimensions of the features of the objects. A classical example of this is the duality of the Platonic solids, in which the cube and the octahedron form a dual pair, the dodecahedron and the icosahedron form a dual pair, and the tetrahedron is self-dual. The dual polyhedron of any of these polyhedra may be formed as the convex hull of the center points of each face of the primal polyhedron, so the vertices of the dual correspond one-for-one with the faces of the primal. Similarly, each edge of the dual corresponds to an edge of the primal, and each face of the dual corresponds to a vertex of the primal. These correspondences are incidence-preserving: if two parts of the primal polyhedron touch each other, so do the corresponding two parts of the dual polyhedron. More generally, using the concept of polar reciprocation, any convex polyhedron, or more generally any convex polytope, corresponds to a dual polyhedron or dual polytope, with an i-dimensional feature of an n-dimensional polytope corresponding to an (n − i − 1)-dimensional feature of the dual polytope. The incidence-preserving nature of the duality is reflected in the fact that the face lattices of the primal and dual polyhedra or polytopes are themselves order-theoretic duals. Duality of polytopes and order-theoretic duality are both involutions: the dual polytope of the dual polytope of any polytope is the original polytope, and reversing all order-relations twice returns to the original order. Choosing a different center of polarity leads to geometrically different dual polytopes, but all have the same combinatorial structure.

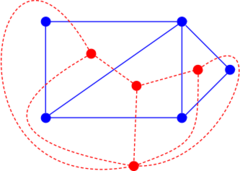

From any three-dimensional polyhedron, one can form a planar graph, the graph of its vertices and edges. The dual polyhedron has a dual graph, a graph with one vertex for each face of the polyhedron and with one edge for every two adjacent faces. The same concept of planar graph duality may be generalized to graphs that are drawn in the plane but that do not come from a three-dimensional polyhedron, or more generally to graph embeddings on surfaces of higher genus: one may draw a dual graph by placing one vertex within each region bounded by a cycle of edges in the embedding, and drawing an edge connecting any two regions that share a boundary edge. An important example of this type comes from computational geometry: the duality for any finite set S of points in the plane between the Delaunay triangulation of S and the Voronoi diagram of S. As with dual polyhedra and dual polytopes, the duality of graphs on surfaces is a dimension-reversing involution: each vertex in the primal embedded graph corresponds to a region of the dual embedding, each edge in the primal is crossed by an edge in the dual, and each region of the primal corresponds to a vertex of the dual. The dual graph depends on how the primal graph is embedded: different planar embeddings of a single graph may lead to different dual graphs. Matroid duality is an algebraic extension of planar graph duality, in the sense that the dual matroid of the graphic matroid of a planar graph is isomorphic to the graphic matroid of the dual graph.

A kind of geometric duality also occurs in optimization theory, but not one that reverses dimensions. A linear program may be specified by a system of real variables (the coordinates for a point in Euclidean space ), a system of linear constraints (specifying that the point lie in a halfspace; the intersection of these halfspaces is a convex polytope, the feasible region of the program), and a linear function (what to optimize). Every linear program has a dual problem with the same optimal solution, but the variables in the dual problem correspond to constraints in the primal problem and vice versa.

Duality in logic and set theory

In logic, functions or relations A and B are considered dual if A(¬x) = ¬B(x), where ¬ is logical negation. The basic duality of this type is the duality of the ∃ and ∀ quantifiers in classical logic. These are dual because ∃x.¬P(x) and ¬∀x.P(x) are equivalent for all predicates P in classical logic: if there exists an x for which P fails to hold, then it is false that P holds for all x (but the converse does not hold constructively). From this fundamental logical duality follow several others:

- A formula is said to be satisfiable in a certain model if there are assignments to its free variables that render it true; it is valid if every assignment to its free variables makes it true. Satisfiability and validity are dual because the invalid formulas are precisely those whose negations are satisfiable, and the unsatisfiable formulas are those whose negations are valid. This can be viewed as a special case of the previous item, with the quantifiers ranging over interpretations.

- In classical logic, the ∧ and ∨ operators are dual in this sense, because (¬x ∧ ¬y) and ¬(x ∨ y) are equivalent. This means that for every theorem of classical logic there is an equivalent dual theorem. De Morgan's laws are examples. More generally, ∧ (¬ xi) = ¬∨ xi. The left side is true if and only if ∀i.¬xi, and the right side if and only if ¬∃i.xi.

- In modal logic, □p means that the proposition p is "necessarily" true, and ◊p that p is "possibly" true. Most interpretations of modal logic assign dual meanings to these two operators. For example in Kripke semantics, "p is possibly true" means "there exists some world W such that p is true in W", while "p is necessarily true" means "for all worlds W, p is true in W". The duality of □ and ◊ then follows from the analogous duality of ∀ and ∃. Other dual modal operators behave similarly. For example, temporal logic has operators denoting "will be true at some time in the future" and "will be true at all times in the future" which are similarly dual.

Other analogous dualities follow from these:

- Set-theoretic union and intersection are dual under the set complement operator ⋅C. That is, AC ∩ BC = (A ∪ B)C, and more generally, ∩ ACα = (∪ Aα)C. This follows from the duality of ∀ and ∃: an element x is a member of ∩ ACα if and only if ∀α.¬x ∈ Aα, and is a member of (∪ Aα)C if and only if ¬∃α. x ∈ Aα.

Dual objects

A group of dualities can be described by endowing, for any mathematical object X, the set of morphisms Hom (X, D) into some fixed object D, with a structure similar to that of X. This is sometimes called internal Hom. In general, this yields a true duality only for specific choices of D, in which case X* = Hom (X, D) is referred to as the dual of X. There is always a map from X to the bidual, that is to say, the dual of the dual, It assigns to some x ∈ X the map that associates to any map f : X → D (i.e., an element in Hom(X, D)) the value f(x). Depending on the concrete duality considered and also depending on the object X, this map may or may not be an isomorphism.

Dual vector spaces revisited

The construction of the dual vector space mentioned in the introduction is an example of such a duality. Indeed, the set of morphisms, i.e., linear maps, forms a vector space in its own right. The map V → V** mentioned above is always injective. It is surjective, and therefore an isomorphism, if and only if the dimension of V is finite. This fact characterizes finite-dimensional vector spaces without referring to a basis.

Isomorphisms of V and V∗ and inner product spaces

A vector space V is isomorphic to V∗ precisely if V is finite-dimensional. In this case, such an isomorphism is equivalent to a non-degenerate bilinear form In this case V is called an inner product space. For example, if K is the field of real or complex numbers, any positive definite bilinear form gives rise to such an isomorphism. In Riemannian geometry, V is taken to be the tangent space of a manifold and such positive bilinear forms are called Riemannian metrics. Their purpose is to measure angles and distances. Thus, duality is a foundational basis of this branch of geometry. Another application of inner product spaces is the Hodge star which provides a correspondence between the elements of the exterior algebra. For an n-dimensional vector space, the Hodge star operator maps k-forms to (n − k)-forms. This can be used to formulate Maxwell's equations. In this guise, the duality inherent in the inner product space exchanges the role of magnetic and electric fields.

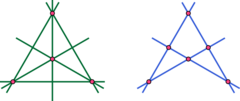

Duality in projective geometry

In some projective planes, it is possible to find geometric transformations that map each point of the projective plane to a line, and each line of the projective plane to a point, in an incidence-preserving way.[10] For such planes there arises a general principle of duality in projective planes: given any theorem in such a plane projective geometry, exchanging the terms "point" and "line" everywhere results in a new, equally valid theorem.[11] A simple example is that the statement "two points determine a unique line, the line passing through these points" has the dual statement that "two lines determine a unique point, the intersection point of these two lines". For further examples, see Dual theorems.

A conceptual explanation of this phenomenon in some planes (notably field planes) is offered by the dual vector space. In fact, the points in the projective plane correspond to one-dimensional subvector spaces [12] while the lines in the projective plane correspond to subvector spaces of dimension 2. The duality in such projective geometries stems from assigning to a one-dimensional the subspace of consisting of those linear maps which satisfy . As a consequence of the dimension formula of linear algebra, this space is two-dimensional, i.e., it corresponds to a line in the projective plane associated to .

The (positive definite) bilinear form yields an identification of this projective plane with the . Concretely, the duality assigns to its orthogonal . The explicit formulas in duality in projective geometry arise by means of this identification.

Topological vector spaces and Hilbert spaces

In the realm of topological vector spaces, a similar construction exists, replacing the dual by the topological dual vector space. There are several notions of topological dual space, and each of them gives rise to a certain concept of duality. A topological vector space that is canonically isomorphic to its bidual is called a reflexive space:

Examples:

- As in the finite-dimensional case, on each Hilbert space H its inner product ⟨⋅, ⋅⟩ defines a map which is a bijection due to the Riesz representation theorem. As a corollary, every Hilbert space is a reflexive Banach space.

- The dual normed space of an Lp-space is Lq where 1/p + 1/q = 1 provided that 1 ≤ p < ∞, but the dual of L∞ is bigger than L1. Hence L1 is not reflexive.

- Distributions are linear functionals on appropriate spaces of functions. They are an important technical means in the theory of partial differential equations (PDE): instead of solving a PDE directly, it may be easier to first solve the PDE in the "weak sense", i.e., find a distribution that satisfies the PDE and, second, to show that the solution must, in fact, be a function.[13] All the standard spaces of distributions — , , — are reflexive locally convex spaces.[14]

Further dual objects

The dual lattice of a lattice L is given by[clarification needed] which is used in the construction of toric varieties.[15] The Pontryagin dual of locally compact topological groups G is given by continuous group homomorphisms with values in the circle (with multiplication of complex numbers as group operation).

Dual categories

Opposite category and adjoint functors

In another group of dualities, the objects of one theory are translated into objects of another theory and the maps between objects in the first theory are translated into morphisms in the second theory, but with direction reversed. Using the parlance of category theory, this amounts to a contravariant functor between two categories C and D:

which for any two objects X and Y of C gives a map

That functor may or may not be an equivalence of categories. There are various situations, where such a functor is an equivalence between the opposite category Cop of C, and D. Using a duality of this type, every statement in the first theory can be translated into a "dual" statement in the second theory, where the direction of all arrows has to be reversed.[16] Therefore, any duality between categories C and D is formally the same as an equivalence between C and Dop (Cop and D). However, in many circumstances the opposite categories have no inherent meaning, which makes duality an additional, separate concept.[17]

A category that is equivalent to its dual is called self-dual. An example of self-dual category is the category of Hilbert spaces.[18]

Many category-theoretic notions come in pairs in the sense that they correspond to each other while considering the opposite category. For example, Cartesian products Y1 × Y2 and disjoint unions Y1 ⊔ Y2 of sets are dual to each other in the sense that

and

for any set X. This is a particular case of a more general duality phenomenon, under which limits in a category C correspond to colimits in the opposite category Cop; further concrete examples of this are epimorphisms vs. monomorphism, in particular factor modules (or groups etc.) vs. submodules, direct products vs. direct sums (also called coproducts to emphasize the duality aspect). Therefore, in some cases, proofs of certain statements can be halved, using such a duality phenomenon. Further notions displaying related by such a categorical duality are projective and injective modules in homological algebra,[19] fibrations and cofibrations in topology and more generally model categories.[20]

Two functors F: C → D and G: D → C are adjoint if for all objects c in C and d in D

in a natural way. Actually, the correspondence of limits and colimits is an example of adjoints, since there is an adjunction

between the colimit functor that assigns to any diagram in C indexed by some category I its colimit and the diagonal functor that maps any object c of C to the constant diagram which has c at all places. Dually,

Spaces and functions

Gelfand duality is a duality between commutative C*-algebras A and compact Hausdorff spaces X is the same: it assigns to X the space of continuous functions (which vanish at infinity) from X to C, the complex numbers. Conversely, the space X can be reconstructed from A as the spectrum of A. Both Gelfand and Pontryagin duality can be deduced in a largely formal, category-theoretic way.[21]

In a similar vein there is a duality in algebraic geometry between commutative rings and affine schemes: to every commutative ring A there is an affine spectrum, Spec A. Conversely, given an affine scheme S, one gets back a ring by taking global sections of the structure sheaf OS. In addition, ring homomorphisms are in one-to-one correspondence with morphisms of affine schemes, thereby there is an equivalence

- (Commutative rings)op ≅ (affine schemes)[22]

Affine schemes are the local building blocks of schemes. The previous result therefore tells that the local theory of schemes is the same as commutative algebra, the study of commutative rings.

Noncommutative geometry draws inspiration from Gelfand duality and studies noncommutative C*-algebras as if they were functions on some imagined space. Tannaka–Krein duality is a non-commutative analogue of Pontryagin duality.[23]

Galois connections

In a number of situations, the two categories which are dual to each other are actually arising from partially ordered sets, i.e., there is some notion of an object "being smaller" than another one. A duality that respects the orderings in question is known as a Galois connection. An example is the standard duality in Galois theory mentioned in the introduction: a bigger field extension corresponds—under the mapping that assigns to any extension L ⊃ K (inside some fixed bigger field Ω) the Galois group Gal (Ω / L) —to a smaller group.[24]

The collection of all open subsets of a topological space X forms a complete Heyting algebra. There is a duality, known as Stone duality, connecting sober spaces and spatial locales.

- Birkhoff's representation theorem relating distributive lattices and partial orders

Pontryagin duality

Pontryagin duality gives a duality on the category of locally compact abelian groups: given any such group G, the character group

- χ(G) = Hom (G, S1)

given by continuous group homomorphisms from G to the circle group S1 can be endowed with the compact-open topology. Pontryagin duality states that the character group is again locally compact abelian and that

- G ≅ χ(χ(G)).[25]

Moreover, discrete groups correspond to compact abelian groups; finite groups correspond to finite groups. On the one hand, Pontryagin is a special case of Gelfand duality. On the other hand, it is the conceptual reason of Fourier analysis, see below.

Analytic dualities

In analysis, problems are frequently solved by passing to the dual description of functions and operators.

Fourier transform switches between functions on a vector space and its dual: and conversely If f is an L2-function on R or RN, say, then so is and . Moreover, the transform interchanges operations of multiplication and convolution on the corresponding function spaces. A conceptual explanation of the Fourier transform is obtained by the aforementioned Pontryagin duality, applied to the locally compact groups R (or RN etc.): any character of R is given by ξ ↦ e−2πixξ. The dualizing character of Fourier transform has many other manifestations, for example, in alternative descriptions of quantum mechanical systems in terms of coordinate and momentum representations.

- Laplace transform is similar to Fourier transform and interchanges operators of multiplication by polynomials with constant coefficient linear differential operators.

- Legendre transformation is an important analytic duality which switches between velocities in Lagrangian mechanics and momenta in Hamiltonian mechanics.

Homology and cohomology

Theorems showing that certain objects of interest are the dual spaces (in the sense of linear algebra) of other objects of interest are often called dualities. Many of these dualities are given by a bilinear pairing of two K-vector spaces

- A ⊗ B → K.

For perfect pairings, there is, therefore, an isomorphism of A to the dual of B.

Poincaré duality

Poincaré duality of a smooth compact complex manifold X is given by a pairing of singular cohomology with C-coefficients (equivalently, sheaf cohomology of the constant sheaf C)

- Hi(X) ⊗ H2n−i(X) → C,

where n is the (complex) dimension of X.[26] Poincaré duality can also be expressed as a relation of singular homology and de Rham cohomology, by asserting that the map

(integrating a differential k-form over an 2n−k-(real) -dimensional cycle) is a perfect pairing.

Poincaré duality also reverses dimensions; it corresponds to the fact that, if a topological manifold is represented as a cell complex, then the dual of the complex (a higher-dimensional generalization of the planar graph dual) represents the same manifold. In Poincaré duality, this homeomorphism is reflected in an isomorphism of the kth homology group and the (n − k)th cohomology group.

Duality in algebraic and arithmetic geometry

The same duality pattern holds for a smooth projective variety over a separably closed field, using l-adic cohomology with Qℓ-coefficients instead.[27] This is further generalized to possibly singular varieties, using intersection cohomology instead, a duality called Verdier duality.[28] Serre duality or coherent duality are similar to the statements above, but applies to cohomology of coherent sheaves instead.[29]

With increasing level of generality, it turns out, an increasing amount of technical background is helpful or necessary to understand these theorems: the modern formulation of these dualities can be done using derived categories and certain direct and inverse image functors of sheaves (with respect to the classical analytical topology on manifolds for Poincaré duality, l-adic sheaves and the étale topology in the second case, and with respect to coherent sheaves for coherent duality).

Yet another group of similar duality statements is encountered in arithmetics: étale cohomology of finite, local and global fields (also known as Galois cohomology, since étale cohomology over a field is equivalent to group cohomology of the (absolute) Galois group of the field) admit similar pairings. The absolute Galois group G(Fq) of a finite field, for example, is isomorphic to , the profinite completion of Z, the integers. Therefore, the perfect pairing (for any G-module M)

- Hn(G, M) × H1−n (G, Hom (M, Q/Z)) → Q/Z[30]

is a direct consequence of Pontryagin duality of finite groups. For local and global fields, similar statements exist (local duality and global or Poitou–Tate duality).[31]

See also

- Adjoint functor

- Autonomous category

- Convex body and polar body.

- Dual abelian variety

- Dual basis

- Dual (category theory)

- Dual code

- Duality (electrical engineering)

- Duality (optimization)

- Dualizing module

- Dualizing sheaf

- Dual lattice

- Dual norm

- Dual numbers, a certain associative algebra; the term "dual" here is synonymous with double, and is unrelated to the notions given above.

- Dual system

- Koszul duality

- Langlands dual

- Linear programming

- List of dualities

- Matlis duality

- Petrie duality

- Pontryagin duality

- S-duality

- T-duality, Mirror symmetry

Notes

- ↑ Atiyah 2007, p. 1

- ↑ Kostrikin 2001, This quote is the first sentence of the final section named comments in this single-paged-document

- ↑ Gowers 2008, p. 187, col. 1

- ↑ Gowers 2008, p. 189, col. 2

- ↑ Atiyah 2007, p. 1

- ↑ The complement is also denoted as S \ A.

- ↑ More precisely, is the smallest closed convex cone containing .

- ↑ Artstein-Avidan & Milman 2007

- ↑ Artstein-Avidan & Milman 2008

- ↑ Veblen & Young 1965.

- ↑ (Veblen & Young 1965, Ch. I, Theorem 11)

- ↑ More generally, one can consider the projective planes over any field, such as the complex numbers or finite fields or even division rings.

- ↑ See elliptic regularity.

- ↑ (Edwards 1965).

- ↑ Fulton 1993

- ↑ Mac Lane 1998, Ch. II.1.

- ↑ (Lam 1999, §19C)

- ↑ Jiří Adámek; J. Rosicky (1994). Locally Presentable and Accessible Categories. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-521-42261-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=iXh6rOd7of0C&pg=PA62.

- ↑ Weibel (1994)

- ↑ Dwyer and Spaliński (1995)

- ↑ Negrepontis 1971.

- ↑ Hartshorne 1966, Ch. II.2, esp. Prop. II.2.3

- ↑ Joyal and Street (1991)

- ↑ See (Lang 2002, Theorem VI.1.1) for finite Galois extensions.

- ↑ (Loomis 1953, p. 151, section 37D)

- ↑ Griffiths & Harris 1994, p. 56

- ↑ Milne 1980, Ch. VI.11

- ↑ Iversen 1986, Ch. VII.3, VII.5

- ↑ Hartshorne 1966, Ch. III.7

- ↑ Milne (2006, Example I.1.10)

- ↑ Mazur (1973); Milne (2006)

References

Duality in general

- Atiyah, Michael (2007). "Duality in Mathematics and Physics lecture notes from the Institut de Matematica de la Universitat de Barcelona (IMUB)". http://www.fme.upc.edu/ca/arxius/butlleti-digital/riemann/071218_conferencia_atiyah-d_article.pdf.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Duality", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=D/d034120.

- Gowers, Timothy (2008), "III.19 Duality", The Princeton Companion to Mathematics, Princeton University Press, pp. 187–190.

- Cartier, Pierre (2001), "A mad day's work: from Grothendieck to Connes and Kontsevich. The evolution of concepts of space and symmetry", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, New Series 38 (4): 389–408, doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-01-00913-2, ISSN 0002-9904, https://www.ams.org/bull/2001-38-04/S0273-0979-01-00913-2/ (a non-technical overview about several aspects of geometry, including dualities)

Duality in algebraic topology

- James C. Becker and Daniel Henry Gottlieb, A History of Duality in Algebraic Topology

Specific dualities

- Artstein-Avidan, Shiri; Milman, Vitali (2008), "The concept of duality for measure projections of convex bodies", Journal of Functional Analysis 254 (10): 2648–66, doi:10.1016/j.jfa.2007.11.008. Also author's site.

- Artstein-Avidan, Shiri; Milman, Vitali (2007), "A characterization of the concept of duality", Electronic Research Announcements in Mathematical Sciences 14: 42–59, http://www.aimsciences.org/journals/pdfs.jsp?paperID=2887&mode=full, retrieved 2009-05-30. Also author's site.

- Dwyer, William G.; Spaliński, Jan (1995), "Homotopy theories and model categories", Handbook of algebraic topology, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 73–126, http://hopf.math.purdue.edu/cgi-bin/generate?/Dwyer-Spalinski/theories

- Fulton, William (1993), Introduction to toric varieties, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-00049-7

- Griffiths, Phillip; Harris, Joseph (1994), Principles of algebraic geometry, Wiley Classics Library, New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-05059-9

- Hartshorne, Robin (1966), Residues and Duality, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 20, Springer-Verlag, pp. 20–48, ISBN 978-3-540-34794-1

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90244-9, OCLC 13348052

- Iversen, Birger (1986), Cohomology of sheaves, Universitext, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-16389-3

- Joyal, André; Street, Ross (1991), "An introduction to Tannaka duality and quantum groups", Category theory, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 1488, Springer-Verlag, pp. 413–492, doi:10.1007/BFb0084235, ISBN 978-3-540-46435-8, http://www.maths.mq.edu.au/~street/CT90Como.pdf

- Lam, Tsit-Yuen (1999), Lectures on modules and rings, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 189, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-98428-5

- Lang, Serge (2002), Algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 211, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-95385-4

- Loomis, Lynn H. (1953), An introduction to abstract harmonic analysis, D. Van Nostrand, pp. x+190

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1998), Categories for the Working Mathematician (2nd ed.), Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-98403-2

- Mazur, Barry (1973), "Notes on étale cohomology of number fields", Annales Scientifiques de l'École Normale Supérieure, Série 4 6 (4): 521–552, doi:10.24033/asens.1257, ISSN 0012-9593

- Milne, James S. (1980), Étale cohomology, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08238-7, https://archive.org/details/etalecohomology00miln

- Milne, James S. (2006), Arithmetic duality theorems (2nd ed.), Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge, LLC, ISBN 978-1-4196-4274-6, http://www.jmilne.org/math/Books/adt.html

- Negrepontis, Joan W. (1971), "Duality in analysis from the point of view of triples", Journal of Algebra 19 (2): 228–253, doi:10.1016/0021-8693(71)90105-0, ISSN 0021-8693

- Veblen, Oswald; Young, John Wesley (1965), Projective geometry. Vols. 1, 2, Blaisdell Publishing Co. Ginn and Co.

- Weibel, Charles A. (1994), An introduction to homological algebra, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55987-4

- Edwards, R. E. (1965). Functional analysis. Theory and applications. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0030505356.

ja:双対