Physics:Matrix representation of Maxwell's equations

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

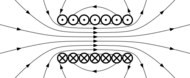

In electromagnetism, a branch of fundamental physics, the matrix representations of the Maxwell's equations are a formulation of Maxwell's equations using matrices, complex numbers, and vector calculus. These representations are for a homogeneous medium, an approximation in an inhomogeneous medium. A matrix representation for an inhomogeneous medium was presented using a pair of matrix equations.[1] A single equation using 4 × 4 matrices is necessary and sufficient for any homogeneous medium. For an inhomogeneous medium it necessarily requires 8 × 8 matrices.[2]

Introduction

Maxwell's equations in the standard vector calculus formalism, in an inhomogeneous medium with sources, are:[3]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & {\mathbf \nabla} \cdot {\mathbf D} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) = \rho\, \\ & {\mathbf \nabla} \times {\mathbf H} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) - \frac{\partial }{\partial t} {\mathbf D} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) = {\mathbf J}\, \\ & {\mathbf \nabla} \times {\mathbf E} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) + \frac{\partial }{\partial t} {\mathbf B} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) = 0\, \\ & {\mathbf \nabla} \cdot {\mathbf B} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) = 0\,. \end{align} }[/math]

The media is assumed to be linear, that is

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathbf D} = \varepsilon \mathbf{E}\,,\quad \mathbf{B} = \mu \mathbf{H} }[/math],

where scalar [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon = \varepsilon(\mathbf{r}, t) }[/math] is the permittivity of the medium and scalar [math]\displaystyle{ \mu = \mu(\mathbf{r}, t) }[/math] the permeability of the medium (see constitutive equation). For a homogeneous medium [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] are constants. The speed of light in the medium is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ v ({\mathbf r} , t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\varepsilon ({\mathbf r} , t)\,\mu ({\mathbf r} , t)\,}} }[/math].

In vacuum, [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon_0 =\, }[/math]8.85 × 10−12 C2·N−1·m−2 and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_0 = 4\pi\, }[/math]× 10−7 H·m−1

One possible way to obtain the required matrix representation is to use the Riemann–Silberstein vector[4][5] given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {\mathbf F}^{+} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) & = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\,}} \left[ \sqrt{\varepsilon ({\mathbf r} , t)\,}\,{\mathbf E} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) + {\rm i}\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu ({\mathbf r} , t)\,}} {\mathbf B} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) \right] \\ {\mathbf F}^{-} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) & = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\,}} \left[ \sqrt{\varepsilon ({\mathbf r} , t)\,}\,{\mathbf E} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) - {\rm i}\,\frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu ({\mathbf r} , t)\,}} {\mathbf B} \left({\mathbf r} , t \right) \right]\,. \end{align} }[/math]

If for a certain medium [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon = \varepsilon(\mathbf{r}, t) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu = \mu(\mathbf{r}, t) }[/math] are scalar constants (or can be treated as local scalar constants under certain approximations), then the vectors [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathbf F}^{\pm}(\mathbf{r}, t) }[/math] satisfy

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {\rm i}\,\frac{\partial }{\partial t} {\mathbf F}^{\pm}\left({\mathbf r} , t \right) & = \pm v\,{\mathbf \nabla} \times {\mathbf F}^{\pm}\left({\mathbf r} , t \right) - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \epsilon\,}} ({\rm i}\,{\mathbf J}) \\ {\mathbf \nabla} \cdot {\mathbf F}^{\pm}\left({\mathbf r} , t \right) & = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \varepsilon\,}} (\rho)\,. \end{align} }[/math]

Thus by using the Riemann–Silberstein vector, it is possible to reexpress the Maxwell's equations for a medium with constant [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon = \varepsilon(\mathbf{r}, t) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu = \mu(\mathbf{r}, t) }[/math] as a pair of constitutive equations.

Homogeneous medium

In order to obtain a single matrix equation instead of a pair, the following new functions are constructed using the components of the Riemann–Silberstein vector[6]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \Psi^{+} ({\mathbf r} , t) & = \left[ \begin{array}{c} - F_x^{+} + {\rm i} F_y^{+} \\ F_z^{+} \\ F_z^{+} \\ F_x^{+} + {\rm i} F_y^{+} \end{array} \right]\, \quad \Psi^{-} ({\mathbf r} , t) = \left[ \begin{array}{c} - F_x^{-} - {\rm i} F_y^{-} \\ F_z^{-} \\ F_z^{-} \\ F_x^{-} - {\rm i} F_y^{-} \end{array} \right]\,. \end{align} }[/math]

The vectors for the sources are

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} W^{+} &= \left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \epsilon}}\right) \left[ \begin{array}{c} - J_x + {\rm i} J_y \\ J_z - v \rho \\ J_z + v \rho \\ J_x + {\rm i} J_y \end{array} \right]\, \quad W^{-} = \left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \epsilon}}\right) \left[ \begin{array}{c} - J_x - {\rm i} J_y \\ J_z - v \rho \\ J_z + v \rho \\ J_x - {\rm i} J_y \end{array} \right]\,. \end{align} }[/math]

Then,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi^{+} &= - v \left\{ {\mathbf M} \cdot {\mathbf \nabla} \right\} \Psi^{+} - W^{+}\, \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi^{-} & = - v \left\{ {\mathbf M}^{*} \cdot {\mathbf \nabla} \right\} \Psi^{-} - W^{-}\, \end{align} }[/math]

where * denotes complex conjugation and the triplet, M = [Mx, My, Mz] is a vector whose component elements are abstract 4×4 matricies given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ M_x = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ M_y = {\rm i} \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 \\ +1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & +1 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ M_z = \begin{bmatrix} +1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & +1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix} \,. }[/math]

The component M-matrices may be formed using:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega = \begin{bmatrix} {\mathbf 0} & - {\mathbf I_2} \\ {\mathbf I_2} & {\mathbf 0} \end{bmatrix} \, \qquad \beta = \begin{bmatrix} {\mathbf I_2} & {\mathbf 0} \\ {\mathbf 0} & - {\mathbf I_2} \end{bmatrix}\,, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf I_2 = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \,, }[/math]

from which, get:

- [math]\displaystyle{ M_x = - \beta \Omega, \qquad M_y = {\rm i} \Omega, \qquad M_z = \beta \,. }[/math]

Alternately, one may use the matrix [math]\displaystyle{ J = -\Omega\,. }[/math] Which only differ by a sign. For our purpose it is fine to use either Ω or J. However, they have a different meaning: J is contravariant and Ω is covariant. The matrix Ω corresponds to the Lagrange brackets of classical mechanics and J corresponds to the Poisson brackets.

Note the important relation [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega = J^{-1}\,. }[/math]

Each of the four Maxwell's equations are obtained from the matrix representation. This is done by taking the sums and differences of row-I with row-IV and row-II with row-III respectively. The first three give the y, x, and z components of the curl and the last one gives the divergence conditions.

The matrices M are all non-singular and all are Hermitian. Moreover, they satisfy the usual (quaternion-like) algebra of the Dirac matrices, including,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} M_x M_z = - M_z M_x\, \\ M_y M_z = - M_z M_y\, \\ \\ M_x^2 = M_y^2 = M_z^2 = I\, \\ \\ M_x M_y = - M_y M_x = {\rm i} M_z\, \\ M_y M_z = - M_z M_y = {\rm i} M_x\, \\ M_z M_x = - M_x M_z = {\rm i} M_y\,. \end{align} }[/math]

The (Ψ±, M) are not unique. Different choices of Ψ± would give rise to different M, such that the triplet M continues to satisfy the algebra of the Dirac matrices. The Ψ± via the Riemann–Silberstein vector has certain advantages over the other possible choices.[5] The Riemann–Silberstein vector is well known in classical electrodynamics and has certain interesting properties and uses.[5]

In deriving the above 4×4 matrix representation of the Maxwell's equations, the spatial and temporal derivatives of ε(r, t) and μ(r, t) in the first two of the Maxwell's equations have been ignored. The ε and μ have been treated as local constants.

Inhomogeneous medium

In an inhomogeneous medium, the spatial and temporal variations of ε = ε(r, t) and μ = μ(r, t) are not zero. That is they are no longer local constant. Instead of using ε = ε(r, t) and μ = μ(r, t), it is advantageous to use the two derived laboratory functions namely the resistance function and the velocity function

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \text{ Velocity function:} \, v ({\mathbf r} , t) & = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\epsilon ({\mathbf r} , t) \mu ({\mathbf r} , t)}} \\ \text{Resistance function:} \, h ({\mathbf r} , t) & = \sqrt{\frac{\mu ({\mathbf r} , t)}{\epsilon ({\mathbf r} , t)}}\,. \end{align} }[/math]

In terms of these functions:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon = \frac{1}{v h}\,,\quad \mu = \frac{h}{v} }[/math].

These functions occur in the matrix representation through their logarithmic derivatives;

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {\mathbf u} ({\mathbf r} , t) & = \frac{1}{2 v ({\mathbf r} , t)} {\mathbf \nabla} v ({\mathbf r} , t) = \frac{1}{2} {\mathbf \nabla} \left\{\ln v ({\mathbf r} , t) \right\} = - \frac{1}{2} {\mathbf \nabla} \left\{\ln n ({\mathbf r} , t) \right\} \\ {\mathbf w} ({\mathbf r} , t) &= \frac{1}{2 h ({\mathbf r} , t)} {\mathbf \nabla} h ({\mathbf r} , t) = \frac{1}{2} {\mathbf \nabla} \left\{\ln h ({\mathbf r} , t) \right\}\, \end{align} }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ n ({\mathbf r} , t) = \frac{c}{v ({\mathbf r} , t)} }[/math]

is the refractive index of the medium.

The following matrices naturally arise in the exact matrix representation of the Maxwell's equation in a medium

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {\mathbf \Sigma} = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} {\mathbf \sigma} & {\mathbf 0} \\ {\mathbf 0} & {\mathbf \sigma} \end{array} \right]\, \qquad {\mathbf \alpha} = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} {\mathbf 0} & {\mathbf \sigma} \\ {\mathbf \sigma} & {\mathbf 0} \end{array} \right]\, \qquad {\mathbf I} = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} {\mathbf 1} & {\mathbf 0} \\ {\mathbf 0} & {\mathbf 1} \end{array} \right]\, \end{align} }[/math]

where Σ are the Dirac spin matrices and α are the matrices used in the Dirac equation, and σ is the triplet of the Pauli matrices

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathbf \sigma} = (\sigma_x , \sigma_y , \sigma_z) = \left[ \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} , \begin{pmatrix} 0 & - {\rm i} \\ {\rm i} & 0 \end{pmatrix} , \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix} \right] }[/math]

Finally, the matrix representation is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \frac{\partial }{\partial t} \left[ \begin{array}{cc} {\mathbf I} & {\mathbf 0} \\ {\mathbf 0} & {\mathbf I} \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \Psi^{+} \\ \Psi^{-} \end{array} \right] - \frac{\dot{v} ({\mathbf r} , t)}{2 v ({\mathbf r} , t)} \left[ \begin{array}{cc} {\mathbf I} & {\mathbf 0} \\ {\mathbf 0} & {\mathbf I} \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \Psi^{+} \\ \Psi^{-} \end{array} \right] + \frac{\dot{h} ({\mathbf r} , t)}{2 h ({\mathbf r} , t)} \left[ \begin{array}{cc} {\mathbf 0} & {\rm i} \beta \alpha_y \\ {\rm i} \beta \alpha_y & {\mathbf 0} \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \Psi^{+} \\ \Psi^{-} \end{array} \right] \\ & = - v ({\mathbf r} , t) \left[ \begin{array}{ccc} \left\{ {\mathbf M} \cdot {\mathbf \nabla} + {\mathbf \Sigma} \cdot {\mathbf u} \right\} & & - {\rm i} \beta \left({\mathbf \Sigma} \cdot {\mathbf w}\right) \alpha_y \\ - {\rm i} \beta \left({\mathbf \Sigma}^{*} \cdot {\mathbf w}\right) \alpha_y & \left\{ {\mathbf M}^{*} \cdot {\mathbf \nabla} + {\mathbf \Sigma}^{*} \cdot {\mathbf u} \right\} \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \Psi^{+} \\ \Psi^{-} \end{array} \right] - \left[ \begin{array}{cc} {\mathbf I} & {\mathbf 0} \\ {\mathbf 0} & {\mathbf I} \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{c} W^{+} \\ W^{-} \end{array} \right]\, \end{align} }[/math]

The above representation contains thirteen 8 × 8 matrices. Ten of these are Hermitian. The exceptional ones are the ones that contain the three components of w(r, t), the logarithmic gradient of the resistance function. These three matrices, for the resistance function are antihermitian.

The Maxwell's equations have been expressed in a matrix form for a medium with varying permittivity ε = ε(r, t) and permeability μ = μ(r, t), in presence of sources. This representation uses a single matrix equation, instead of a pair of matrix equations. In this representation, using 8 × 8 matrices, it has been possible to separate the dependence of the coupling between the upper components (Ψ+) and the lower components (Ψ−) through the two laboratory functions. Moreover, the exact matrix representation has an algebraic structure very similar to the Dirac equation.[2] Maxwell's equations can be derived from the Fermat's principle of geometrical optics by the process of "wavization"[clarification needed] analogous to the quantization of classical mechanics.[7]

Applications

One of the early uses of the matrix forms of the Maxwell's equations was to study certain symmetries, and the similarities with the Dirac equation.

The matrix form of the Maxwell's equations is used as a candidate for the Photon Wavefunction.[8]

Historically, the geometrical optics is based on the Fermat's principle of least time. Geometrical optics can be completely derived from the Maxwell's equations. This is traditionally done using the Helmholtz equation. The derivation of the Helmholtz equation from the Maxwell's equations is an approximation as one neglects the spatial and temporal derivatives of the permittivity and permeability of the medium. A new formalism of light beam optics has been developed, starting with the Maxwell's equations in a matrix form: a single entity containing all the four Maxwell's equations. Such a prescription is sure to provide a deeper understanding of beam-optics and polarization in a unified manner.[9] The beam-optical Hamiltonian derived from this matrix representation has an algebraic structure very similar to the Dirac equation, making it amenable to the Foldy-Wouthuysen technique.[10] This approach is very similar to one developed for the quantum theory of charged-particle beam optics.[11]

References

Notes

- ↑ (Bialynicki-Birula, 1994, 1996a, 1996b)

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 (Khan, 2002, 2005)

- ↑ (Jackson, 1998; Panofsky and Phillips, 1962)

- ↑ Silberstein (1907a, 1907b)

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bialynicki-Birula (1996b)

- ↑ Khan (2002, 2005)

- ↑ (Pradhan, 1987)

- ↑ (Bialynicki-Birula, 1996b)

- ↑ (Khan, 2006b, 2010)

- ↑ (Khan, 2006a, 2008)

- ↑ (Jagannathan et al., 1989, Jagannathan, 1990, Jagannathan and Khan 1996, Khan, 1997)

Others

- Bialynicki-Birula, I. (1994). On the wave function of the photon. Acta Physica Polonica A, 86, 97–116.

- Bialynicki-Birula, I. (1996a). The Photon Wave Function. In Coherence and Quantum Optics VII. Eberly, J. H., Mandel, L. and Emil Wolf (ed.), Plenum Press, New York, 313.

- Bialynicki-Birula, I. (1996b). Photon wave function. in Progress in Optics, Vol. XXXVI, Emil Wolf. (ed.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, 245–294.

- Jackson, J. D. (1998). Classical Electrodynamics, Third Edition, John Wiley & Sons.

- Jagannathan, R. , (1990). Quantum theory of electron lenses based on the Dirac equation. Physical Review A, 42, 6674–6689.

- Jagannathan, R. and Khan, S. A. (1996). Quantum theory of the optics of charged particles. In Hawkes Peter, W. (ed.), Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics, Vol. 97, Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 257–358.

- Jagannathan, R. , Simon, R., Sudarshan, E. C. G. and Mukunda, N. (1989). Quantum theory of magnetic electron lenses based on the Dirac equation. Physics Letters A 134, 457–464.

- Khan, S. A. (1997). Quantum Theory of Charged-Particle Beam Optics, Ph.D Thesis, University of Madras, Chennai, India . (complete thesis available from Dspace of IMSc Library, The Institute of Mathematical Sciences, where the doctoral research was done).

- Sameen Ahmed Khan. (2002). Maxwell Optics: I. An exact matrix representation of the Maxwell equations in a medium. E-Print: https://arxiv.org/abs/physics/0205083/.

- Sameen Ahmed Khan. (2005). An Exact Matrix Representation of Maxwell's Equations. Physica Scripta, 71(5), 440–442.

- Sameen Ahmed Khan. (2006a). The Foldy-Wouthuysen Transformation Technique in Optics. Optik-International Journal for Light and Electron Optics. 117(10), pp. 481–488 http://www.elsevier-deutschland.de/ijleo/.

- Sameen Ahmed Khan. (2006b). Wavelength-Dependent Effects in Light Optics. in New Topics in Quantum Physics Research, Editors: Volodymyr Krasnoholovets and Frank Columbus, Nova Science Publishers, New York, pp. 163–204. (ISBN:1600210287 and ISBN:978-1600210280).

- Sameen Ahmed Khan. (2008). The Foldy-Wouthuysen Transformation Technique in Optics, In Hawkes Peter, W. (ed.), Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics, Vol. 152, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 49–78. (ISBN:0123742196 and ISBN:978-0-12-374219-3).

- Sameen Ahmed Khan. (2010). Maxwell Optics of Quasiparaxial Beams, Optik-International Journal for Light and Electron Optics, 121(5), 408–416. (http://www.elsevier-deutschland.de/ijleo/).

- Laporte, O., and Uhlenbeck, G. E. (1931). Applications of spinor analysis to the Maxwell and Dirac Equations. Physical Review, 37, 1380–1397.

- Majorana, E. (1974). (unpublished notes), quoted after Mignani, R., Recami, E., and Baldo, M. About a Diraclike Equation for the Photon, According to Ettore Majorana. Lettere al Nuovo Cimento, 11, 568–572.

- Moses, E. (1959).Solutions of Maxwell's equations in terms of a spinor notation: the direct and inverse problems. Physical Review, 113(6), 1670–1679.

- Panofsky, W. K. H., and Phillips, M. (1962). Classical Electricity and Magnetics, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, Massachusetts, USA.

- Pradhan, T. (1987). Maxwell's Equations From Geometrical Optics. IP/BBSR/87-15; Physics Letters A 122(8), 397–398.

- Ludwig Silberstein. (1907a). Elektromagnetische Grundgleichungen in bivektorieller Behandlung, Ann. Phys. (Leipzig), 22, 579–586.

- Ludwig Silberstein. (1907b). Nachtrag zur Abhandlung ber Elektromagnetische Grundgleichungen in bivektorieller Behandlung. Ann. Phys. (Leipzig), 24, 783–784.

|