Planetary surface

— (Full-sized image)

A planetary surface is where the solid or liquid material of certain types of astronomical objects contacts the atmosphere or outer space. Planetary surfaces are found on solid objects of planetary mass, including terrestrial planets (including Earth), dwarf planets, natural satellites, planetesimals and many other small Solar System bodies (SSSBs).[1][2][3] The study of planetary surfaces is a field of planetary geology known as surface geology, but also a focus on a number of fields including planetary cartography, topography, geomorphology, atmospheric sciences, and astronomy. Land (or ground) is the term given to non-liquid planetary surfaces. The term landing is used to describe the collision of an object with a planetary surface and is usually at a velocity in which the object can remain intact and remain attached.

In differentiated bodies, the surface is where the crust meets the planetary boundary layer. Anything below this is regarded as being sub-surface or sub-marine. Most bodies more massive than super-Earths, including stars and gas giants, as well as smaller gas dwarfs, transition contiguously between phases, including gas, liquid, and solid. As such, they are generally regarded as lacking surfaces.

Planetary surfaces and surface life are of particular interest to humans as it is the primary habitat of the species, which has evolved to move over land and breathe air. Human space exploration and space colonization therefore focuses heavily on them. Humans have only directly explored the surface of Earth and the Moon. The vast distances and complexities of space makes direct exploration of even near-Earth objects dangerous and expensive. As such, all other exploration has been indirect via space probes.

Indirect observations by flyby or orbit currently provide insufficient information to confirm the composition and properties of planetary surfaces. Much of what is known is from the use of techniques such as astronomical spectroscopy and sample return. Lander spacecraft have explored the surfaces of planets Mars and Venus. Mars is the only other planet to have had its surface explored by a mobile surface probe (rover). Titan is the only non-planetary object of planetary mass to have been explored by lander. Landers have explored several smaller bodies including 433 Eros (2001), 25143 Itokawa (2005), Tempel 1 (2005), 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko (2014), 162173 Ryugu (2018) and 101955 Bennu (2020). Surface samples have been collected from the Moon (returned 1969), 25143 Itokawa (returned 2010), 162173 Ryugu and 101955 Bennu.

Distribution and conditions

Planetary surfaces are found throughout the Solar System, from the inner terrestrial planets, to the asteroid belt, the natural satellites of the gas giant planets and beyond to the Trans-Neptunian objects. Surface conditions, temperatures and terrain vary significantly due to a number of factors including Albedo often generated by the surfaces itself. Measures of surface conditions include surface area, surface gravity, surface temperature and surface pressure. Surface stability may be affected by erosion through Aeolian processes, hydrology, subduction, volcanism, sediment or seismic activity. Some surfaces are dynamic while others remain unchanged for millions of years.

Exploration

Distance, gravity, atmospheric conditions (extremely low or extremely high atmospheric pressure) and unknown factors make exploration both costly and risky. This necessitates the space probes for early exploration of planetary surfaces. Many probes are stationary have a limited study range and generally survive on extraterrestrial surfaces for a short period, however mobile probes (rovers) have surveyed larger surface areas. Sample return missions allow scientist to study extraterrestrial surface materials on Earth without having to send a crewed mission, however is generally only feasible for objects with low gravity and atmosphere.

Past missions

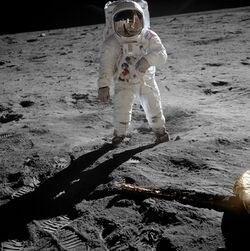

The first extraterrestrial planetary surface to be explored was the lunar surface by Luna 2 in 1959. The first and only human exploration of an extraterrestrial surface was the Moon, the Apollo program included the first moonwalk on July 20, 1969, and successful return of extraterrestrial surface samples to Earth. Venera 7 was the first landing of a probe on another planet on December 15, 1970. Mars 3 "soft landed" and returned data from Mars on August 22, 1972, the first rover on Mars was Mars Pathfinder in 1997, the Mars Exploration Rover has been studying the surface of the red planet since 2004. NEAR Shoemaker was the first to soft land on an asteroid – 433 Eros in February 2001 while Hayabusa was the first to return samples from 25143 Itokawa on 13 June 2010. Huygens soft landed and returned data from Titan on January 14, 2005.

There have been many failed attempts, more recently Fobos-Grunt, a sample return mission aimed at exploring the surface of Phobos.

Forms

The surfaces of Solar System objects, other than the four Outer Solar System gas planets, are mostly solid, with few having liquid surfaces.

In general terrestrial planets have either surfaces of ice, or surface crusts of rock or regolith, with distinct terrains. Water ice predominates surfaces in the Solar System beyond the frost line in the Outer Solar System, with a range of icy celestial bodies. Rock and regolith is common in the Inner Solar System until Mars.

The only Solar System object having a mostly liquid surface is Earth, with its global ocean surface comprising 70.8 % of Earth's surface, filling its oceanic basins and covering Earth's oceanic crust, making Earth an ocean world. The remaining part of its surface consists of rocky or organic carbon and silicon rich compounds.

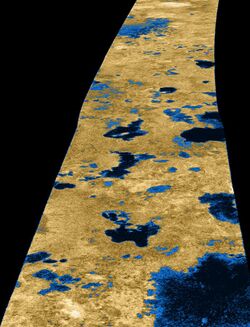

Liquid water as surface, beside on Earth, has only been found, as seasonal flows on warm Martian slopes, as well as past occurrences, and suspected at the habitable zones of other planetary systems. Surface liquid of any kind, has been found notably on Titan, having large methane lakes, some of which are the largest known lakes in the Solar System.

Volcanism can cause flows such as lava on the surface of geologically active bodies (the largest being the Amirani (volcano) flow on Io). Many of Earth's Igneous rocks are formed through processes rare elsewhere, such as the presence of volcanic magma and water. Surface mineral deposits such as olivine and hematite discovered on Mars by lunar rovers provide direct evidence of past stable water on the surface of Mars.

Apart from water, many other abundant surface materials are unique to Earth in the Solar System as they are not only organic but have formed due to the presence of life – these include carbonate hardgrounds, limestone, vegetation and artificial structures although the latter is present due to probe exploration (see also List of artificial objects on extra-terrestrial surfaces).

Extraterrestrial Organic compounds

Increasingly organic compounds are being found on objects throughout the Solar System. While unlikely to indicate the presence of extraterrestrial life, all known life is based on these compounds. Complex carbon molecules may form through various complex chemical interactions or delivered through impacts with small solar system objects and can combine to form the "building blocks" of Carbon-based life. As organic compounds are often volatile, their persistence as a solid or liquid on a planetary surface is of scientific interest as it would indicate an intrinsic source (such as from the object's interior) or residue from larger quantities of organic material preserved through special circumstances over geological timescales, or an extrinsic source (such as from past or recent collision with other objects).[6] Radiation makes the detection of organic matter difficult, making its detection on atmosphereless objects closer to the Sun extremely difficult.[7]

Examples of likely occurrences include:

- Tholins – many Trans Neptunian Objects including Pluto-Charon,[8] Titan,[9] Triton,[10] Eris,[11] Sedna,[12] 28978 Ixion,[13] 90482 Orcus,[14] 24 Themis[15][16]

- Methane clathrate (CH4·5.75H2O) – Oberon, Titania, Umbriel, Pluto, 90482 Orcus, Comet 67P

On Mars

Martian exploration including samples taken by on the ground rovers and spectroscopy from orbiting satellites have revealed the presence of a number of complex organic molecules, some of which could be biosignatures in the search for life.

- Thiophene (C4H4S)[17]

- Polythiophene (polymer of C4H4S)[18]

- Methanethiol (CH3SH)[19]

- Dimethyl sulfide (CH2S)[19]

On Ceres

- Ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3).[20][21]

- Gilsonite[22]

On Enceladus

- Methylamine/Ethylamine[23] (CH3 NH2)

- Acetaldehyde[23] (CH3 CHO)

On Comet 67P

The space probe Philae (spacecraft) discovered the following organic compounds on the surface of Comet 67P:.[24][25][26]

- Acetamide (CH3CONH2)

- Acetone (CH3)2CO

- Methyl isocyanate (CH3NCO)

- Propionaldehyde (CH3CH2CHO)

Inorganic materials

The following is a non-exhaustive list of surface materials that occur on more than one planetary surface along with their locations in order of distance from the Sun. Some have been detected by spectroscopy or direct imaging from orbit or flyby.

- Ice (H2O) – Mercury (polar); Earth-Moon system;[27] Mars (polar); Ceres[28] and some asteroids such as 24 Themis;[29] Jupiter moons – Europa,[30] Ganymede and Callisto; Triton,;[31] Saturn moons – Titan and Enceladus; Uranus moons – Miranda, Umbriel, Oberon; Kuiper belt objects including Pluto-Charon system, Haumea, 28978 Ixion, 90482 Orcus, 50000 Quaoar

- Silicate rock – Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, asteroids, Ganymede, Callisto, Moon, Triton

- Regolith – Mercury;[32] Venus,[33] Earth-Moon system; Mars (and its moons Phobos and Deimos); asteroids (including 4 Vesta[34]); Titan

- Nitrogen ice (N) – Pluto–Charon,[35] Triton,[36] Kuiper belt objects, Plutinos

- Sulphur (S) – Mercury; Earth; Mars; Jupiter moons – Io and Europa

Rare inorganics

- Salts – Earth, Mars, Ceres, Europa and Jupiter Trojans,[37] Enceladus[38]

- Clays – Earth; Mars;[39] asteroids including Ceres[40] and Tempel 1;[41] Europa[42]

- Sand – Earth, Mars, Titan

- Calcium carbonate (CaCO3) – Earth, Mars[43][44]

- Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) – Earth, Ceres[45][46][47]

Carbon Ices

- Carbon monoxide ice (CO) - Triton[51]

Landforms

Common rigid surface features include:

- Impact craters (though rarer on bodies with thick atmospheres, the largest being Hellas Planitia on Mars)

- Dunes as found on Venus, Earth, Mars and Titan

- volcanoes and cryovolcanoes

- Rilles

- Mountains (the highest being Rheasilvia on 4 Vesta)[citation needed]

- Escarpments

- Canyons and valleys (the largest being Valles Marineris on Mars)

- Caves

- Lava tubes, found on Venus, Earth, The Moon and Mars

Surface of gas giants

Normally, gas giants are considered to not have a surface, although they might have a solid core of rock or various types of ice, or a liquid core of metallic hydrogen. However, the core, if it exists, does not include enough of the planet's mass to be actually considered a surface. Some scientists consider the point at which the atmospheric pressure is equal to 1 bar, equivalent to the atmospheric pressure at Earth's surface, to be the surface of the planet,[1] if the planet has no clear rigid terrain. Therefore the location of the surface of terrestrial planets do not depend on an atmospheric pressure of 1 Bar, even if for example Venus has a thick atmosphere with pressures at Venus's surface increasing well above Earth's atmospheric pressure.

Life

Planetary surfaces are investigated for the presence of past or present extraterrestrial life. Thomas Gold expanded the field by advancing the possibility of life and a so-called deep biosphere below the surface of a celestial body, and not only on the surface.[53]

Surface chauvinism and surfacism

Furthermore, Thomas Gold has criticized science which only focuses on the surface and not below in its search of life as surface chauvinism.[53]

Similarly the focus on surface bound and territorial space advocacy, particularly for space colonization such as of Mars, has been named surfacism, neglecting interest for atmospheres and potential atmospheric human habitation, such as above the surface of Venus.[54][55]

Gallery

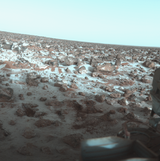

-

The dry, rocky and icy surface of planet Mars (photographed by Viking Lander 2, May 1979) is composed of iron-oxide rich regolith

-

Pebbled plains of Saturn's moon Titan (photographed by Huygens probe, January 14, 2005) composed of heavily compressed states of water ice. This is the only ground-based photograph of an outer Solar System planetary surface

-

Surface of comet Tempel 1 (photographed by the Deep Impact probe), consists of a fine powder of contains water and carbon dioxide rich clays, carbonates, sodium, and crystalline silicates.

See also

- Extraterrestrial atmosphere

- Hydrosphere

- Subsurface ocean

- Ocean world

- Planetary radius

- Planetary geoid

References

- ↑ Meyer, Charles; Treiman, Allanh; Kostiuk, Theodor (May 12–13, 1995). Meyer, Charles. ed. Planetary Surface Instruments Workshop. Houston, Texas. p. 3. Bibcode: 1996psi..work.....M. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/publications/psiw/psiw.pdf. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- ↑ "Planetary Surface materials". Haskin Research Group. http://epsc.wustl.edu/haskin-group/.

- ↑ Melosh, Jay (August 2007). Planetary Surface Processes. Cambridge Planetary Science. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-521-51418-7.

- ↑ "Venera 9's landing site" (in en). https://www.planetary.org/space-images/20120907_venera_9_panorama_stryk.

- ↑ "Venera 9's landing site" (in en). https://www.planetary.org/space-images/20120907_venera_9_panorama_stryk.

- ↑ Ehrenfreund, P.; Spaans, M.; Holm, N. G. (2011). "The evolution of organic matter in space". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 369 (1936): 538–554. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0231. PMID 21220279. Bibcode: 2011RSPTA.369..538E.

- ↑ Anders, Edward (1989). "Pre-biotic organic matter from comets and asteroids". Nature 342 (6247): 255–257. doi:10.1038/342255a0. PMID 11536617. Bibcode: 1989Natur.342..255A.

- ↑ Grundy, W. M.; Cruikshank, D. P.; Gladstone, G. R.; Howett, C. J. A.; Lauer, T. R.; Spencer, J. R.; Summers, M. E.; Buie, M. W. et al. (2016). "The formation of Charon's red poles from seasonally cold-trapped volatiles". Nature 539 (7627): 65–68. doi:10.1038/nature19340. PMID 27626378. Bibcode: 2016Natur.539...65G.

- ↑ McCord, T. B.; Hansen, G. B.; Buratti, B. J.; Clark, R. N.; Cruikshank, D. P.; D’Aversa, E.; Griffith, C. A.; Baines, E. K. H. et al. (2006). "Composition of Titan's surface from Cassini VIMS". Planetary and Space Science 54 (15): 1524–1539. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2006.06.007. Bibcode: 2006P&SS...54.1524M.

- ↑ Grundy, W. M.; Buie, M. W.; Spencer, J. R. (October 2002). "Spectroscopy of Pluto and Triton at 3–4 Microns: Possible Evidence for Wide Distribution of Nonvolatile Solids". The Astronomical Journal 124 (4): 2273–2278. doi:10.1086/342933. Bibcode: 2002AJ....124.2273G.

- ↑ Brown, Michael E., Trujillo, Chadwick A., Rabinowitz, David L. (2005). "Discovery of a Planetary-sized Object in the Scattered Kuiper Belt". The Astrophysical Journal 635 (1): L97–L100. doi:10.1086/499336. Bibcode: 2005ApJ...635L..97B.

- ↑ Barucci, M. A.; Cruikshank, D. P.; Dotto, E.; Merlin, F.; Poulet, F.; Dalle Ore, C.; Fornasier, S.; De Bergh, C. (2005). "Is Sedna another Triton?". Astronomy & Astrophysics 439 (2): L1–L4. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500144. Bibcode: 2005A&A...439L...1B.

- ↑ Boehnhardt, H. et al. (2004). "Surface characterization of 28978 Ixion (2001 KX76)". Astronomy and Astrophysics Letters 415 (2): L21–L25. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20040005. Bibcode: 2004A&A...415L..21B.

- ↑ de Bergh, C. (2005). "The Surface of the Transneptunian Object 9048 Orcus". Astronomy & Astrophysics 437 (3): 1115–20. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042533. Bibcode: 2005A&A...437.1115D.

- ↑ Omar, M. H.; Dokoupil, Z. (May 1962). "Solubility of nitrogen and oxygen in liquid hydrogen at temperatures between 27 and 33K". Physica 28 (5): 461–471. doi:10.1016/0031-8914(62)90033-2. Bibcode: 1962Phy....28..461O.

- ↑ Rivkin, Andrew S.; Emery, Joshua P. (2010). "Detection of ice and organics on an asteroidal surface". Nature 464 (7293): 1322–1323. doi:10.1038/nature09028. PMID 20428165. Bibcode: 2010Natur.464.1322R. (pdf version accessed 28 Feb. 2018).

- ↑ Voosen, Paul (2018). "NASA rover hits organic pay dirt on Mars". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aau3992.

- ↑ Mukbaniani, O. V.; Aneli, J. N.; Markarashvili, E. G.; Tarasashvili, M. V.; Aleksidze, N. D. (2015). "Polymeric composites on the basis of Martian ground for building future mars stations". International Journal of Astrobiology 15 (2): 155–160. doi:10.1017/S1473550415000270. ISSN 1473-5504.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Eigenbrode, Jennifer L.; Summons, Roger E.; Steele, Andrew; Freissinet, Caroline; Millan, Maëva; Navarro-González, Rafael; Sutter, Brad; McAdam, Amy C. et al. (2018). "Organic matter preserved in 3-billion-year-old mudstones at Gale crater, Mars". Science 360 (6393): 1096–1101. doi:10.1126/science.aas9185. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29880683. Bibcode: 2018Sci...360.1096E. http://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/bitstream/10044/1/60810/2/aas9185_CombinedPDF_v2.pdf.

- ↑ Vu, Tuan H; Hodyss, Robert; Johnson, Paul V; Choukroun, Mathieu (2017). "Preferential formation of sodium salts from frozen sodium-ammonium-chloride-carbonate brines – Implications for Ceres' bright spots". Planetary and Space Science 141: 73–77. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2017.04.014. Bibcode: 2017P&SS..141...73V.

- ↑ McCord, Thomas B; Zambon, Francesca (2018). "The surface composition of Ceres from the Dawn mission". Icarus 318: 2–13. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.03.004. Bibcode: 2019Icar..318....2M.

- ↑ De Sanctis, M. C.; Ammannito, E.; McSween, H. Y.; Raponi, A.; Marchi, S.; Capaccioni, F.; Capria, M. T.; Carrozzo, F. G. et al. (2017). "Localized aliphatic organic material on the surface of Ceres". Science 355 (6326): 719–722. doi:10.1126/science.aaj2305. PMID 28209893. Bibcode: 2017Sci...355..719D.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Khawaja, N; Postberg, F; Hillier, J; Klenner, F; Kempf, S; Nölle, L; Reviol, R; Zou, Z et al. (2019). "Low-mass nitrogen-, oxygen-bearing, and aromatic compounds in Enceladean ice grains". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 489 (4): 5231–5243. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz2280. ISSN 0035-8711. Bibcode: 2019MNRAS.489.5231K.

- ↑ Jordans, Frank (30 July 2015). "Philae probe finds evidence that comets can be cosmic labs". The Washington Post. Associated Press. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/philae-probe-finds-evidence-that-comets-can-be-cosmic-labs/2015/07/30/63a2fc0e-36e5-11e5-ab7b-6416d97c73c2_story.html.

- ↑ "Science on the Surface of a Comet". European Space Agency. 30 July 2015. http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Rosetta/Science_on_the_surface_of_a_comet.

- ↑ Bibring, J.-P.; Taylor, M.G.G.T.; Alexander, C.; Auster, U.; Biele, J.; Finzi, A. Ercoli; Goesmann, F.; Klingehoefer, G. et al. (31 July 2015). "Philae's First Days on the Comet – Introduction to Special Issue". Science 349 (6247): 493. doi:10.1126/science.aac5116. PMID 26228139. Bibcode: 2015Sci...349..493B.

- ↑ Williams, David R. (10 December 2012). "Ice on the Moon". NASA. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/ice/ice_moon.html.

- ↑ Choi, Charles Q. (December 15, 2016) Water Ice Found On Dwarf Planet Ceres, Hidden in Permanent Shadow. Space.com]

- ↑ Moskowitz, Clara (2010-04-28). "Water Ice Discovered on Asteroid for First Time". Space.com. http://www.space.com/8305-water-ice-discovered-asteroid-time.html.

- ↑ "Europa: Another Water World?". Project Galileo: Moons and Rings of Jupiter. NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2001. http://teachspacescience.org/cgi-bin/search.plex?catid=10000304&mode=full.

- ↑ McKinnon, William B.; Kirk, Randolph L. (2007). "Encyclopedia of the Solar System". in Lucy Ann Adams McFadden. Encyclopedia of the Solar System (2nd ed.). Amsterdam; Boston: Academic Press. pp. 483–502. ISBN 978-0-12-088589-3. https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofso0000unse_u6d1/page/483.

- ↑ Langevin, Y (1997). "The regolith of Mercury: present knowledge and implications for the Mercury Orbiter mission". Planetary and Space Science 45 (1): 31–37. doi:10.1016/s0032-0633(96)00098-0. Bibcode: 1997P&SS...45...31L.

- ↑ Scott, Keith; Pain, Colin (18 August 2009). Regolith Science. Csiro Publishing. pp. 390–. ISBN 978-0-643-09996-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=mo-MUnoPmN4C&pg=PA390.

- ↑ Pieters, C. M.; Ammannito, E.; Blewett, D. T.; Denevi, B. W.; De Sanctis, M. C.; Gaffey, M. J.; Le Corre, L.; Li, J. -Y. et al. (2012). "Distinctive space weathering on Vesta from regolith mixing processes". Nature 491 (7422): 79–82. doi:10.1038/nature11534. PMID 23128227. Bibcode: 2012Natur.491...79P.

- ↑ "Flowing nitrogen ice glaciers seen on surface of Pluto after New Horizons flyby". 25 July 2015. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-07-25/flowing-nitrogen-ice-glaciers-seen-on-surface-of-pluto/6647636.

- ↑ McKinnon, William B.; Kirk, Randolph L. (2014). "Encyclopedia of the Solar System". in Spohn, Tilman; Breuer, Doris; Johnson, Torrence. Encyclopedia of the Solar System (3rd ed.). Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier. pp. 861–82. ISBN 978-0-12-416034-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=0bEMAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA861.

- ↑ Yang, Bin; Lucey, Paul; Glotch, Timothy (2013). "Are large Trojan asteroids salty? An observational, theoretical, and experimental study". Icarus 223 (1): 359–366. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.11.025. Bibcode: 2013Icar..223..359Y.

- ↑ Deziel, Chris (April 25, 2017). "Salt on Other Planets". Sciencing. http://sciencing.com/salt-other-planets-23945.html.

- ↑ Clays On Mars: More Plentiful Than Expected. Science Daily. December 20, 2012

- ↑ Rivkin, A.S; Volquardsen, E.L; Clark, B.E (2006). "The surface composition of Ceres: Discovery of carbonates and iron-rich clays". Icarus 185 (2): 563–567. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.08.022. Bibcode: 2006Icar..185..563R. http://irtfweb.ifa.hawaii.edu/~elv/icarus185.563.pdf.

- ↑ Napier, W.M.; Wickramasinghe, J.T.; Wickramasinghe, N.C. (2007). "The origin of life in comets". International Journal of Astrobiology 6 (4): 321. doi:10.1017/S1473550407003941. Bibcode: 2007IJAsB...6..321N.

- ↑ "Clay-Like Minerals Found on Icy Crust of Europa". JPL, NASA.gov. December 11, 2013. http://www.nasa.gov/jpl/news/europa-clay-like-minerals-20131211.html.

- ↑ Boynton, WV; Ming, DW; Kounaves, SP et al. (2009). "Evidence for Calcium Carbonate at the Mars Phoenix Landing Site". Science 325 (5936): 61–64. doi:10.1126/science.1172768. PMID 19574384. Bibcode: 2009Sci...325...61B. http://planetary.chem.tufts.edu/Boynton%20etal%20Science%202009v325p61.pdf.

- ↑ Clark, B. C; Arvidson, R. E; Gellert, R et al. (2007). "Evidence for montmorillonite or its compositional equivalent in Columbia Hills, Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research 112 (E6): E06S01. doi:10.1029/2006JE002756. Bibcode: 2007JGRE..112.6S01C. http://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/17119/1/Clark2007_Evidence_for_montmorillonite_or_its_compositional_equivalent_in_Columbia_Hills_Mars.pdf.

- ↑ Landau, Elizabeth; Greicius, Tony (29 June 2016). "Recent Hydrothermal Activity May Explain Ceres' Brightest Area". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/feature/jpl/recent-hydrothermal-activity-may-explain-ceres-brightest-area.

- ↑ Lewin, Sarah (29 June 2016). "Mistaken Identity: Ceres Mysterious Bright Spots Aren't Epsom Salt After All". Space.com. http://www.space.com/33302-ceres-bright-spots-new-composition.html.

- ↑ De Sanctis, M. C. (29 June 2016). "Bright carbonate deposits as evidence of aqueous alteration on (1) Ceres". Nature 536 (7614): 54–57. doi:10.1038/nature18290. PMID 27362221. Bibcode: 2016Natur.536...54D.

- ↑ Kounaves, S. P. (2014). "Evidence of martian perchlorate, chlorate, and nitrate in Mars meteorite EETA79001: implications for oxidants and organics". Icarus 229: 169. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.11.012. Bibcode: 2014Icar..229..206K.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Grundy, W. M.; Young, L. A.; Spencer, J. R.; Johnson, R. E.; Young, E. F.; Buie, M. W. (October 2006). "Distributions of H2O and CO2 ices on Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon from IRTF/SpeX observations". Icarus 184 (2): 543–555. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.04.016. Bibcode: 2006Icar..184..543G.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Jones, Brant M.; Kaiser, Ralf I.; Strazzulla, Giovanni (2014). "Carbonic acid as a reserve of carbon dioxide on icy moons: The formation of carbon dioxide (CO2) in a polar environment". The Astrophysical Journal 788 (2): 170. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/788/2/170. Bibcode: 2014ApJ...788..170J.

- ↑ Lellouch, E.; de Bergh, C.; Sicardy, B.; Ferron, S.; Käufl, H.-U. (2010). "Detection of CO in Triton's atmosphere and the nature of surface-atmosphere interactions". Astronomy and Astrophysics 512: L8. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014339. Bibcode: 2010A&A...512L...8L.

- ↑ Gipson, Lillian (24 July 2015). "New Horizons Discovers Flowing Ices on Pluto". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/feature/new-horizons-discovers-flowing-ices-on-pluto.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Gold, Thomas (1999). The Deep Hot Biosphere. New York, NY: Springer New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1400-7. ISBN 978-0-387-95253-6.

- ↑ Tickle, Glen (2015-03-05). "A Look Into Whether Humans Should Try to Colonize Venus Instead of Mars". https://laughingsquid.com/a-look-into-whether-humans-should-try-to-colonize-venus-instead-of-mars/.

- ↑ David Warmflash (14 March 2017). "Colonization of the Venusian Clouds: Is 'Surfacism' Clouding Our Judgement?" (in en). https://www.visionlearning.com/blog/2017/03/14/colonization-venusian-clouds-surfacism-clouding-judgement/.

|

![Venera 9 returned the first view and this first clear image from the surface of another planet in 1975 (Venus).[5]](/wiki/images/thumb/f/ff/Foto_de_Venera_9.png/500px-Foto_de_Venera_9.png)