Disdyakis triacontahedron

| Disdyakis triacontahedron | |

|---|---|

(rotating and 3D model) | |

| Type | Catalan |

| Conway notation | mD or dbD |

| Coxeter diagram | |

| Face polygon |  scalene triangle |

| Faces | 120 |

| Edges | 180 |

| Vertices | 62 = 12 + 20 + 30 |

| Face configuration | V4.6.10 |

| Symmetry group | Ih, H3, [5,3], (*532) |

| Rotation group | I, [5,3]+, (532) |

| Dihedral angle | |

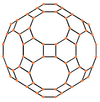

| Dual polyhedron |  truncated icosidodecahedron |

| Properties | convex, face-transitive |

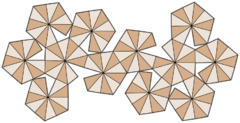

net | |

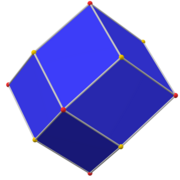

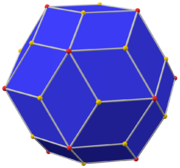

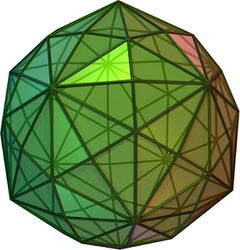

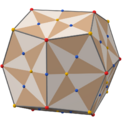

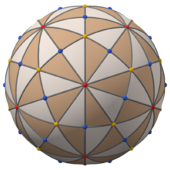

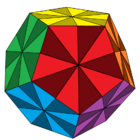

In geometry, a disdyakis triacontahedron, hexakis icosahedron, decakis dodecahedron or kisrhombic triacontahedron[1] is a Catalan solid with 120 faces and the dual to the Archimedean truncated icosidodecahedron. As such it is face-uniform but with irregular face polygons. It slightly resembles an inflated rhombic triacontahedron: if one replaces each face of the rhombic triacontahedron with a single vertex and four triangles in a regular fashion, one ends up with a disdyakis triacontahedron. That is, the disdyakis triacontahedron is the Kleetope of the rhombic triacontahedron. It is also the barycentric subdivision of the regular dodecahedron and icosahedron. It has the most faces among the Archimedean and Catalan solids, with the snub dodecahedron, with 92 faces, in second place.

If the bipyramids, the gyroelongated bipyramids, and the trapezohedra are excluded, the disdyakis triacontahedron has the most faces of any other strictly convex polyhedron where every face of the polyhedron has the same shape.

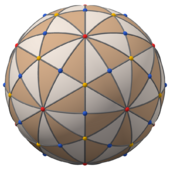

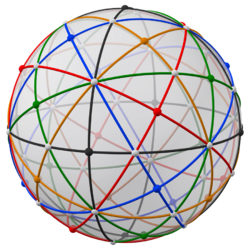

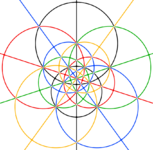

Projected into a sphere, the edges of a disdyakis triacontahedron define 15 great circles. Buckminster Fuller used these 15 great circles, along with 10 and 6 others in two other polyhedra to define his 31 great circles of the spherical icosahedron.

Geometry

Being a Catalan solid with triangular faces, the disdyakis triacontahedron's three face angles and common dihedral angle must obey the following constraints analogous to other Catalan solids:

The above four equations are solved simultaneously to get the following face angles and dihedral angle:

where is the golden ratio.

As with all Catalan solids, the dihedral angles at all edges are the same, even though the edges may be of different lengths.

Cartesian coordinates

The 62 vertices of a disdyakis triacontahedron are given by:[2]

- Twelve vertices and their cyclic permutations,

- Eight vertices ,

- Twelve vertices and their cyclic permutations,

- Six vertices and their cyclic permutations.

- Twenty-four vertices and their cyclic permutations,

where

- ,

- , and

- is the golden ratio.

In the above coordinates, the first 12 vertices form a regular icosahedron, the next 20 vertices (those with R) form a regular dodecahedron, and the last 30 vertices (those with S) form an icosidodecahedron.

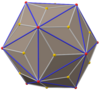

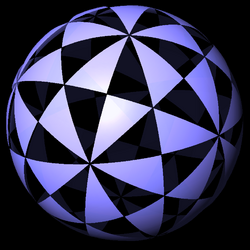

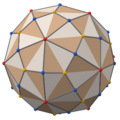

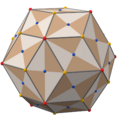

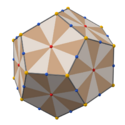

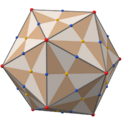

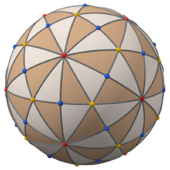

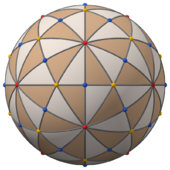

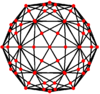

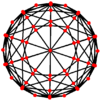

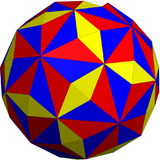

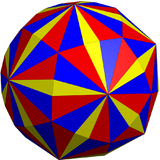

Normalizing all vertices to the unit sphere gives a spherical disdyakis triacontahedron, shown in the adjacent figure. This figure also depicts the 120 transformations associated with the full icosahedral group Ih.

Symmetry

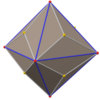

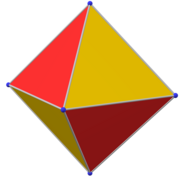

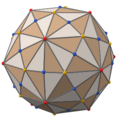

The edges of the polyhedron projected onto a sphere form 15 great circles, and represent all 15 mirror planes of reflective Ih icosahedral symmetry. Combining pairs of light and dark triangles define the fundamental domains of the nonreflective (I) icosahedral symmetry. The edges of a compound of five octahedra also represent the 10 mirror planes of icosahedral symmetry.

Disdyakis triacontahedron |

Deltoidal hexecontahedron |

Rhombic triacontahedron |

Dodecahedron |

Icosahedron |

Pyritohedron |

| Spherical polyhedron | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| (see rotating model) | Orthographic projections from 2-, 3- and 5-fold axes | ||

| Stereographic projections | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 2-fold | 3-fold | 5-fold | |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| Colored as compound of five octahedra, with 3 great circles for each octahedron. The area in the black circles below corresponds to the frontal hemisphere of the spherical polyhedron. | |||

Orthogonal projections

The disdyakis triacontahedron has three types of vertices which can be centered in orthogonally projection:

| Projective symmetry |

[2] | [6] | [10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image |

|

|

|

| Dual image |

|

|

|

Uses

The disdyakis triacontahedron, as a regular dodecahedron with pentagons divided into 10 triangles each, is considered the "holy grail" for combination puzzles like the Rubik's cube. This unsolved problem, often called the "big chop" problem, currently has no satisfactory mechanism. It is the most significant unsolved problem in mechanical puzzles.[3]

This shape was used to make d120 dice using 3D printing.[4] Since 2016, the Dice Lab has used the disdyakis triacontahedron to mass market an injection moulded 120 sided die.[5] It is claimed that the d120 is the largest number of possible faces on a fair die, aside from infinite families (such as right regular prisms, bipyramids, and trapezohedra) that would be impractical in reality due to the tendency to roll for a long time.[6]

A disdyakis tricontahedron projected onto a sphere is used as the logo for Brilliant, a website containing series of lessons on STEM-related topics.[7]

Related polyhedra and tilings

|

|

| Polyhedra similar to the disdyakis triacontahedron are duals to the Bowtie icosahedron and dodecahedron, containing extra pairs of triangular faces.[8] | |

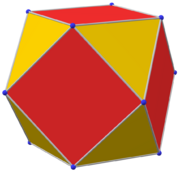

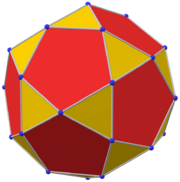

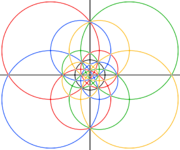

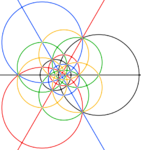

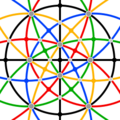

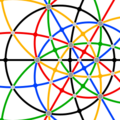

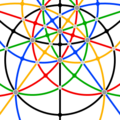

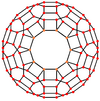

It is topologically related to a polyhedra sequence defined by the face configuration V4.6.2n. This group is special for having all even number of edges per vertex and form bisecting planes through the polyhedra and infinite lines in the plane, and continuing into the hyperbolic plane for any n ≥ 7.

With an even number of faces at every vertex, these polyhedra and tilings can be shown by alternating two colors so all adjacent faces have different colors.

Each face on these domains also corresponds to the fundamental domain of a symmetry group with order 2,3,n mirrors at each triangle face vertex. This is *n32 in orbifold notation, and [n,3] in Coxeter notation.

References

- ↑ Conway, Symmetries of things, p.284

- ↑ DisdyakisTriacontahedron

- ↑ Big Chop

- ↑ Kevin Cook's Dice Collector website: d120 3D printed from Shapeways artist SirisC

- ↑ The Dice Lab

- ↑ "This D120 is the Largest Mathematically Fair Die Possible | Nerdist". http://nerdist.com/this-d120-is-the-largest-mathematically-fair-die-possible/.

- ↑ "Brilliant | Learn to think" (in en-us). https://brilliant.org/.

- ↑ Symmetrohedra: Polyhedra from Symmetric Placement of Regular Polygons Craig S. Kaplan

- Williams, Robert (1979). The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A Source Book of Design. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-23729-X. (Section 3-9)

- Wenninger, Magnus (1983), Dual Models, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511569371, ISBN 978-0-521-54325-5 (The thirteen semiregular convex polyhedra and their duals, Page 25, Disdyakistriacontahedron)

- The Symmetries of Things 2008, John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, ISBN:978-1-56881-220-5 [1] (Chapter 21, Naming the Archimedean and Catalan polyhedra and tilings, page 285, kisRhombic triacontahedron)

External links

- Eric W. Weisstein, Disdyakis triacontahedron (Catalan solid) at MathWorld.

- Disdyakis triacontahedron (Hexakis Icosahedron) – Interactive Polyhedron Model

|