Regular icosahedron

| Regular icosahedron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Deltahedron, Gyroelongated bipyramid, Platonic solid, Regular polyhedron |

| Faces | 20 |

| Edges | 30 |

| Vertices | 12 |

| Vertex configuration | |

| Schläfli symbol | |

| Symmetry group | icosahedral symmetry |

| Dihedral angle (degrees) | 138.190 (approximately) |

| Dual polyhedron | regular dodecahedron |

| Properties | convex, composite, isogonal, isohedral, isotoxal |

| Net | |

| |

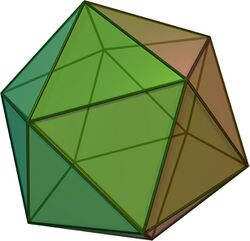

The regular icosahedron (or simply icosahedron) is a convex polyhedron that can be constructed from pentagonal antiprism by attaching two pentagonal pyramids with regular faces to each of its pentagonal faces, or by putting points onto the cube. The resulting polyhedron has 20 equilateral triangles as its faces, 30 edges, and 12 vertices. It is an example of a Platonic solid and of a deltahedron. The icosahedral graph represents the skeleton of a regular icosahedron.

Many polyhedra and other related figures are constructed from the regular icosahedron, including its 59 stellations. The great dodecahedron, one of the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra, is constructed by either stellation of the regular dodecahedron or faceting of the icosahedron. Some of the Johnson solids can be constructed by removing the pentagonal pyramids. The regular icosahedron's dual polyhedron is the regular dodecahedron, and their relation has a historical background in the comparison mensuration. It is analogous to a four-dimensional polytope, the 600-cell.

Regular icosahedra can be found in nature; a well-known example is the capsid in biology. Other applications of the regular icosahedron are the usage of its net in cartography, and the twenty-sided dice that may have been used in ancient times but are now commonplace in modern tabletop role-playing games.

Construction

The regular icosahedron is a twenty-sided polyhedron wherein the faces are equilateral triangles. It is one of the eight convex deltahedra, a polyhedron wherein all of its faces are equilateral triangles.[1] Variously, it can be constructed as follows:

- Started by attaching two pentagonal pyramids with regular faces to the base of a pentagonal antiprism. These components are elementaries—they cannot be disintegrated into smaller convex polyhedra with regular faces again. Replacing bases of a pentagonal antiprism with ten triangular pyramids,[2] the regular icosahedron is classified as a composite polyhedron, the opposite of an elementary polyhedron.[3] This construction led to the alternative names called bicapped pentagonal antiprism,[4] or gyroelongated pentagonal bipyramid due to its construction process through gyroelongation—polyhedra construction by attaching two pyramids onto the base of an antiprism.[5]

- The twelve vertices of a regular icosahedron describe the three mutually perpendicular golden rectangular planes, whose corners are connected. These rectangular planes can be constructed from a pair of vertices located on the midpoints of the opposite edges on a cube's surface, drawing a segment line between those two, and divides the segment line in a golden ratio from its midpoint.[6] Both the vertices of a regular icosahedron have an edge length of 2 and the three planes can be illustrated through Cartesian coordinate system:[7]

- One can snub a regular octahedron, by separating all of its faces and filling them with more equilateral triangles. As suggested by the process, the regular icosahedron is also known as snub octahedron.[8]

The regular icosahedron can be unfolded into 43,380 different nets.[9] The earliest net appeared in Albrecht Durer's Painter's Manual in 1525.[10]

Properties

Surface area and volume

File:Regular icosahedron.stl The surface area of a polyhedron is the sum of the areas of its faces. In the case of a regular icosahedron, its surface area is twenty times that of each of its equilateral triangle faces. Its volume can be obtained as twenty times that of a pyramid whose base is one of its faces and whose apex is the regular icosahedron's center; or as the sum of the volume of two uniform pentagonal pyramids and a pentagonal antiprism. Given that the edge length of a regular icosahedron, both expressions are:[11]

Relation to the spheres

The insphere of a convex polyhedron is a sphere touching every polyhedron's face within. The circumsphere of a convex polyhedron is a sphere that contains the polyhedron and touches every vertex. The midsphere of a convex polyhedron is a sphere tangent to every edge. Given that the edge length of a regular icosahedron, the radius of insphere (inradius) , the radius of circumsphere (circumradius) , and the radius of midsphere (midradius) are, respectively:[12]

A problem dating back to the ancient Greeks is determining which of two shapes has a larger volume: a regular icosahedron inscribed in a sphere, or a regular dodecahedron inscribed in the same sphere. The problem was solved by Hero, Pappus, and Fibonacci, among others.[13] Apollonius of Perga discovered the curious result that the ratio of volumes of these two shapes is the same as the ratio of their surface areas.[14] Both volumes have formulas involving the golden ratio, but taken to different powers.[15] As it turns out, the regular icosahedron occupies less of the sphere's volume (60.54%) than the regular dodecahedron (66.49%).[lower-alpha 1]

Other measurements

The dihedral angle of a regular icosahedron is , where is the golden ratio. This angle is about 138.19°, and can be calculated by adding the angle of pentagonal pyramids with regular faces and a pentagonal antiprism. The dihedral angle of a pentagonal antiprism and pentagonal pyramid between two adjacent triangular faces is approximately 38.2°. The dihedral angle of a pentagonal antiprism between pentagon-to-triangle is 100.8°, and the dihedral angle of a pentagonal pyramid between the same faces is 37.4°. Therefore, for the regular icosahedron, the dihedral angle between two adjacent triangles, on the edge where the pentagonal pyramid and pentagonal antiprism are attached, is 37.4° + 100.8° = 138.2°.[16]

The regular icosahedron has three types of closed geodesics. These are paths on its surface that are locally straight: they avoid the polyhedron's vertices, follow line segments across the faces that they cross, and form complementary angles on the two incident faces of each edge that they cross. The first geodesic forms a regular decagon perpendicular to the longest diagonal and has the length . The other two geodesics are non-planar, with lengths and .[17]

Symmetry

The regular icosahedron has the thirty-one axes of rotational symmetry (that is, rotating around an axis that results in an identical appearance). There are six axes passing through two opposite vertices, ten axes rotating a triangular face, and fifteen axes passing through any of its edges. Respectively, these axes are five-fold rotational symmetry (0°, 72°, 144°, 216°, and 288°), three-fold rotational symmetry (0°, 120°, and 240°), and two-fold rotational symmetry (0° and 180°).[18] The regular icosahedron also has fifteen mirror planes that can be represented as great circles on a sphere. It divides the surface of a sphere into 120 triangles fundamental domains; these triangles are called Mobius triangles. Both reflections and rotational symmetries are the isometries—transformations in order to maintain the appearance—which forms the full icosahedral symmetry of order 120.[19] This symmetry group is isomorphic to the product of the rotational symmetry group and the cyclic group of size two, generated by the reflection through the center of the regular icosahedron.[20]

The rotational symmetry group of the regular icosahedron is isomorphic to the alternating group on five letters. This non-abelian simple group is the only non-trivial normal subgroup of the symmetric group on five letters.[21] Since the Galois group of the general quintic equation is isomorphic to the symmetric group on five letters, and this normal subgroup is simple and non-abelian, the general quintic equation does not have a solution in radicals. The proof of the Abel–Ruffini theorem uses this simple fact,[22] and Felix Klein wrote a book that made use of the theory of icosahedral symmetries to derive an analytical solution to the general quintic equation.[23]

The regular icosahedron is isogonal, isohedral, and isotoxal: any two vertices, two faces, and two edges of a regular icosahedron can be transformed by rotations and reflections under its symmetry orbit, which preserves the appearance. Each regular polyhedron has a convex hull on its edge midpoints; icosidodecahedron is the convex hull of a regular icosahedron.[24] Each vertex is surrounded by five equilateral triangles, so the regular icosahedron denotes in vertex configuration or in Schläfli symbol.[25]

Appearances

Toys

Dice are among the most common objects that utilize different polyhedra, one of which is the regular icosahedron. The twenty-sided die was found in ancient times. One example is the die from Ptolemaic Egypt, which was later used with Greek letters inscribed on the faces in the period of Greece and Rome.[26] Another example was found in the treasure of Tipu Sultan, which was made out of gold and with numbers written on each face.[27]

In several roleplaying games, such as Dungeons & Dragons, the twenty-sided die (labeled as d20) is commonly used in determining success or failure of an action. It may be numbered from "0" to "9" twice, in which form it usually serves as a ten-sided die (d10); most modern versions are labeled from "1" to "20".[28] Scattergories is another board game in which the player names the category entries on a card within a given set time. The naming of such categories is initially with the letters contained in every twenty-sided dice.[29]

Natural forms and sciences

In virology, herpes virus have icosahedral shells, especially well-known in adenovirus.[30] The outer protein shell of HIV is enclosed in a regular icosahedron, as is the head of a typical myovirus.[31] Several species of radiolarians discovered by Ernst Haeckel, described their shells as like-shaped various regular polyhedra; one of which is Circogonia icosahedra, whose skeleton is shaped like a regular icosahedron.[32]

In chemistry, the closo-carboranes are compounds with a shape resembling the regular icosahedron.[33] The crystal twinning with icosahedral shapes also occurs in crystals, especially nanoparticles.[34] Many borides and allotropes of boron such as α- and β-rhombohedral contain boron B12 icosahedron as a basic structure unit.[35]

In cartography, R. Buckminster Fuller used the net of a regular icosahedron to create a map known as Dymaxion map, by subdividing the net into triangles, followed by calculating the grid on the Earth's surface, and transferring the results from the sphere to the polyhedron. This projection was created during the time that Fuller realized that Greenland is smaller than South America.[36]

In the Thomson problem, concerning the minimum-energy configuration of charged particles on a sphere, and for the Tammes problem of constructing a spherical code maximizing the smallest distance among the points, the minimum solution known for places the points at the vertices of a regular icosahedron, inscribed in a sphere. This configuration is proven optimal for the Tammes problem, and also for the Thomas problem.[37]

In tensegrity, the regular icosahedron is composed of six struts and twenty-four cables that connect twelve nodes. One self-stress state is present within the combination achieved through the use of cellular morphogenesis.[38]

Ancient texts

The regular icosahedron is one of the five Platonic solids. The regular polyhedra have been known since antiquity, but are named after Plato who, in his Timaeus dialogue, identified these with the five elements, whose elementary units were attributed these shapes: fire (tetrahedron), air (octahedron), water (icosahedron), earth (cube) and the shape of the universe as a whole (dodecahedron). Euclid's Elements defined the Platonic solids and solved the problem of finding the ratio of the circumscribed sphere's diameter to the edge length.[39]

Following their identification with the elements by Plato, Johannes Kepler in his Harmonices Mundi sketched each of them, in particular, the regular icosahedron.[40] In his Mysterium Cosmographicum, he also proposed a model of the Solar System based on the placement of Platonic solids in a concentric sequence of increasing radius of the inscribed and circumscribed spheres whose radii gave the distance of the six known planets from the common center. The ordering of the solids, from innermost to outermost, consisted of: regular octahedron, regular icosahedron, regular dodecahedron, regular tetrahedron, and cube.[41]

Leonardo da Vinci's Divina proportione drew both regular icosahedron and dodecahedron.[42]

Representation

As a graph

Every Platonic graph, including the icosahedral graph, is a polyhedral graph: they can be drawn in the plane without crossing its edges, and the removal of any two of its vertices leaves a connected subgraph. According to Steinitz's theorem, the icosahedral graph endowed with these heretofore properties represents the skeleton of a regular icosahedron.[43]

The icosahedral graph has twelve vertices, the same number of vertices as a regular icosahedron. These vertices are connected by five edges from each vertex, making the icosahedral graph 5-regular.[44] The icosahedral graph is Hamiltonian, because it has a cycle that can visit each vertex exactly once.[45] Any subset of four vertices has three connected edges, with one being the central of all of those three, and the icosahedral graph has no induced subgraph, a claw-free graph.[46]

The icosahedral graph is a graceful graph, meaning that each vertex can be labeled with an integer between 0 and 30 inclusive, in such a way that the absolute difference between the labels of an edge's two vertices is different for every edge.[47]

As a configuration matrix

The regular icosahedron can be represented as a configuration matrix, a matrix in which the rows and columns correspond to the elements of a polyhedron as the vertices, edges, and faces. The diagonal of a matrix denotes the number of each element that appears in a polyhedron, whereas the non-diagonal of a matrix denotes the number of the column's elements that occur in or at the row's element. The following matrix is:[48]

Related figures

Inscribed in other Platonic solids

The regular icosahedron is the dual polyhedron of the regular dodecahedron. A regular icosahedron can be inscribed in a regular dodecahedron by placing its vertices at the face centers of the regular dodecahedron, and vice versa. The regular dodecahedron has icosahedral symmetry.[49]

Apart from the construction above, the regular icosahedron can be inscribed in a regular octahedron by placing its twelve vertices on the twelve edges of the octahedron such that they divide each edge in the golden section. Because the resulting segments are unequal, there are five different ways to do this consistently, so five disjoint icosahedra can be inscribed in each octahedron.[50] Another relation between the two is that they are part of the progressive transformation from the cuboctahedron's rigid struts and flexible vertices, known as jitterbug transformation.[51]

A regular icosahedron of edge length can be inscribed in a unit-edge-length cube by placing six of its edges—three orthogonal opposite pairs—on the square faces of the cube, centered on the face centers and parallel or perpendicular to the square's edges.[52] Because there are five times as many icosahedron edges as cube faces, there are five ways to do this consistently, so five disjoint icosahedra can be inscribed in each cube. The edge lengths of the cube and the inscribed icosahedron are in the golden ratio.[citation needed]

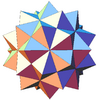

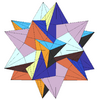

Stellations

The regular icosahedron has a large number of stellations, constructed by extending the faces of a regular icosahedron. (Coxeter du Val) in their work, The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra, identified fifty-nine stellations for the regular icosahedron. The regular icosahedron itself is the zeroth stellation of an icosahedron, and the first stellation has each original face augmented by a low pyramid. The final stellation includes all of the cells in the icosahedron's stellation diagram, meaning every three intersecting face planes of the icosahedral core intersect either on a vertex of this polyhedron or inside it.[53]

Faceting

The great dodecahedron has other ways to construct from the regular icosahedron. Aside from the stellation, the great dodecahedron can be constructed by faceting the regular icosahedron, that is, removing the pentagonal faces of the regular icosahedron without removing the vertices or creating a new one; or forming a regular pentagon by each of the five vertices inside of a regular icosahedron, and twelve regular pentagons intersecting each other, making a pentagram as its vertex figure.[54]

Other polyhedra construction

The triakis icosahedron is a Catalan solid constructed by attaching the base of triangular pyramids onto each face of a regular icosahedron, the Kleetope of an icosahedron.[55] The truncated icosahedron is an Archimedean solid constructed by truncating the vertices of a regular icosahedron; the resulting polyhedron may be considered as a football because of having a pattern of numerous hexagonal and pentagonal faces,[56] or a structural form of carbon known as buckminsterfullerene that has 60 carbon atoms bonded together.[57]

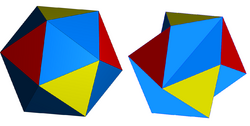

A Johnson solid is a polyhedron whose faces are all regular but which is not uniform. In other words, they do not include the Archimedean solids, the Catalan solids, the prisms, or the antiprisms. Some Johnson solids can be derived by removing part of a regular icosahedron, a process known as diminishment. They are gyroelongated pentagonal pyramid, metabidiminished icosahedron, and tridiminished icosahedron, which remove one, two, and three pentagonal pyramids from the icosahedron, respectively.[58]

The edge-contracted icosahedron has a surface like a regular icosahedron but with some faces lie in the same plane.[59]

Spherical icosahedron

The spherical icosahedron represents a regular icosahedron projected to a sphere, a part of spherical polyhedron. It can be modeled by the arc of great circles, creating bounds as the edges of spherical triangle.[60] Identified by R. Buckminster Fuller, there are 31 great circles in a spherical icosahedron.[61] Its dual is the spherical dodecahedron.[60] The appearance of this shape may be found in Impossiball, a similar toy to Rubik's Cube.[62]

Miscellaneous

Another related shape can be derived by keeping the vertices of a regular icosahedron in their original positions and replacing certain pairs of equilateral triangles with pairs of isosceles triangles. The resulting polyhedron has the non-convex version of the regular icosahedron. Nonetheless, it is occasionally incorrectly known as Jessen's icosahedron because of the similar visual, of having the same combinatorial structure and symmetry as Jessen's icosahedron;[lower-alpha 2] the difference is that the non-convex one does not form a tensegrity structure and does not have right-angled dihedrals.[63]

The regular icosahedron is analogous to the 600-cell, a regular 4-dimensional polytope.[64] This polytope has six hundred regular tetrahedra as its cells.[65] The regular icosahedron is a cell for the honeycomb in a hyperbolic three-dimensional space.[66]

See also

- Binary icosahedral group, a double cover of the group of rotations of the icosahedron

- Icosian, a set of quaternions with the same symmetry

- Dehn invariant

- Disdyakis triacontahedron, a 120-sided convex polyhedron whose faces are the fundamental domains in icosahedral symmetry. Six such regions can be painted on each face of an icosahedron

- Dogic, an icosahedral version of Rubik's Cube

- Geodesic grid

- Geodesic polyhedron

- Goldberg polyhedron, a convex polyhedron made from hexagons and pentagons with icosahedral symmetry

- Hemi-icosahedron

- Polyhedral map projection, map projections taking the globe to a polyhedron

- Rhombic triacontahedron, a 30-sided convex polyhedron with icosahedral symmetry whose faces lie in the 2-fold symmetry planes

- Tensegrity icosahedron

- Tetrahedral-icosahedral honeycomb, another hyperbolic honeycomb involving some icosahedral cells

- Zometool, a construction toy based on the icosahedral symmetry system

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Numerical values for the volumes of the inscribed Platonic solids may be found in Buker & Eggleton 1969.

- ↑ Incorrect descriptions of Jessen's icosahedron as having the same vertex positions as a regular icosahedron include: Wells 1991, p. 161; Jessen's Orthogonal Icosahedron on MathWorld (old version, subsequently fixed).

Notes

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Timofeenko 2010.

- ↑ King 2020.

- ↑ Gailiunas 2023, p. 339.

- ↑ Cromwell 1997, p. 70.

- ↑

- Steeb, Hardy & Tanski 2012, p. 211

- Rees 2000, p. 48

- ↑ Kappraff 1991, p. 475.

- ↑ Dennis et al. 2018, p. 169.

- ↑ Hart 1998, p. 198.

- ↑

- ↑

- MacLean 2007, pp. 43–44

- Coxeter 1973, Table I(i), pp. 292–293. See column "", where is Coxeter's notation for the midradius, also noting that Coxeter uses as the edge length (see p. 2).

- ↑ Herz-Fischler 2013, pp. 138–140.

- ↑ Simmons 2007, p. 50.

- ↑ Sutton 2002, p. 55.

- ↑

- Johnson 1966, See table II, line 4.

- MacLean 2007, pp. 43–44

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Hart 1998, p. 196.

- ↑ Seidel 1991, p. 364.

- ↑ Gray 2018, p. 371.

- ↑ Rotman 1998, pp. 74–75.

- ↑

- Klein 1884. See related geometries of that symmetry group for further history and related symmetries on seven and eleven letters.

- Klein 1888

- ↑ Senechal 1989, p. 12.

- ↑ Walter & Deloudi 2009, p. 50.

- ↑

- ↑ Cromwell 1997, p. 4.

- ↑ "Dungeons & Dragons Dice". https://www.gmdice.com/pages/dungeons-dragons-dice.

- ↑ Flanagan & Gregory 2015, p. 85.

- ↑ Gallardo et al. 2021.

- ↑ Strauss & Strauss 2008, p. 35–62.

- ↑

- Haeckel 1904

- Cromwell 1997, p. 6

- Hart 1998, p. 197

- ↑ Spokoyny 2013.

- ↑ Hofmeister 2004.

- ↑ Dronskowski, Kikkawa & Stein 2017, pp. 435–436.

- ↑ Cromwell 1997, p. 7.

- ↑

- ↑ Aloui et al. 2019.

- ↑ Heath 1908, pp. 262, 478, 480.

- ↑ Cromwell 1997, p. 55.

- ↑ Livio 2003, p. 147.

- ↑ Hart 1998, p. 195.

- ↑ Bickle 2020, p. 147.

- ↑ Fallat & Hogben 2014, p. 29, Section 46.

- ↑ Hopkins 2004.

- ↑ Chudnovsky & Seymour 2005.

- ↑ Gallian 1998.

- ↑ Coxeter 1973, sec 1.8 Configurations.

- ↑

- Erickson 2011, p. 62

- Herrmann & Sally 2013, p. 257

- ↑ Coxeter et al. 1938, p. 4.

- ↑ Verheyen 1989.

- ↑ Borovik 2006, pp. 8–9, §5. How to draw an icosahedron on a blackboard.

- ↑

- Coxeter et al. 1938, pp. 8–26

- Coxeter et al. 1999, pp. 30–31

- Wenninger 1971, p. 65

- ↑

- Inchbald 2006

- Pugh 1976a, p. 85

- Barnes 2012, p. 46

- ↑ Brigaglia, Palladino & Vaccaro 2018.

- ↑

- ↑ Katz 2006, p. 361.

- ↑ Berman 1971.

- ↑ Tsuruta 2024, p. 112.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Yackel 2013.

- ↑

- Fuller 1982, pp. 183–185

- Popko 2012, pp. 22–25

- ↑ Joyner 2008, p. 82.

- ↑ Pugh 1976b, p. 11, 26.

- ↑ Barnes 2012, p. 79.

- ↑ Stillwell 2005, p. 173.

- ↑ Coxeter 1999, p. 212–213.

Bibliographies

- Aloui, Omar; Flores, Jessica; Orden, David; Rhode-Barbarigos, Landolf (2019). "Cellular morphogenesis of three-dimensional tensegrity structures". Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 346: 85–108. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2018.10.048. ISSN 0045-7825. Bibcode: 2019CMAME.346...85A. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0045782518305814.

- Andreev, N. N. (1996). "An extremal property of the icosahedron". East Journal on Approximations 2 (4): 459–462.

- Barnes, John (2012). Gems of Geometry (2nd ed.). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30964-9. ISBN 978-3-642-30964-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=7YCUBUd-4BQC.

- Berman, Martin (1971). "Regular-faced convex polyhedra". Journal of the Franklin Institute 291 (5): 329–352. doi:10.1016/0016-0032(71)90071-8.

- Bickle, Allan (2020). Fundamentals of Graph Theory. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-1-4704-5549-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=2sbVDwAAQBAJ.

- Coxeter Theory: The Cognitive Aspects. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society. 2006. pp. 17–43. ISBN 978-0821837221.

- Brigaglia, Aldo; Palladino, Nicla; Vaccaro, Maria Alessandra (2018). "Historical notes on star geometry in mathematics, art and nature". in Emmer, Michele; Abate, Marco. Imagine Math 6: Between Culture and Mathematics. Springer International Publishing. pp. 197–211. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93949-0_17. ISBN 978-3-319-93948-3.

- Buker, W. E.; Eggleton, R. B. (1969). "The Platonic Solids (Solution to problem E2053)". American Mathematical Monthly 76 (2): 192. doi:10.2307/2317282.

- Cann, Alan (2012). Principles of Molecular Virology (5th ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12384939-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=mDbsN9LvE8gC.

- Chancey, C. C.; O'Brien, M. C. M. (1997). The Jahn-Teller Effect in C60 and Other Icosahedral Complexes. Princeton University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-691-22534-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=wcQIEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA13.

- Bridget S. Webb, ed (2005). "The structure of claw-free graphs". Surveys in combinatorics 2005. London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series (327). Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–171. ISBN 978-0-511-73488-5. https://www.math.princeton.edu/~mchudnov/claws_survey.pdf.

- The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra. 6. University of Toronto Studies (Mathematical Series). 1938.

- "2.1 Regular polyhedra; 2.2 Reciprocation". Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover Publications. 1973. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-486-61480-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=iWvXsVInpgMC&pg=PA16.

- The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra (3rd ed.). Tarquin. 1999. ISBN 978-1-899618-32-3.

- The Beauty of Geometry: Twelve Essays. Dover Publications. 1999. ISBN 978-0-486-40919-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=p4o-Uf-i-IUC.

- Cromwell, Peter R. (1997). Polyhedra. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55432-9. https://archive.org/details/polyhedra0000crom.

- Cundy, H. Martyn (1952). "Deltahedra". The Mathematical Gazette 36 (318): 263–266. doi:10.2307/3608204.

- Dennis, L.; McNair, J. Brender; Woolf, N. J.; Kauffman, L. H. (2018). "The Context – Form Informing Function". Mereon Matrix, The: Everything Connected Through (K)nothing. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-323-357-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=4hVeDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA143.

- Dronskowski, Richard; Kikkawa, Shinichi; Stein, Andreas (2017). Handbook of Solid State Chemistry, 6 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-69103-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=e0VBDwAAQBAJ.

- Erickson, Martin (2011). Beautiful Mathematics. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-1-61444-509-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=LgeP62-ZxikC.

- Fallat, Shaun M.; Hogben, Lesley (2014). "Minimum Rank, Maximum Nullity, and Zero Forcing Number of Graphs". in Hogben, Leslie. Handbook of Linear Algebra. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-0728-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=8hnYCwAAQBAJ&pg=SA46.

- Flanagan, Kieran; Gregory, Dan (2015). Selfish, Scared and Stupid: Stop Fighting Human Nature and Increase Your Performance, Engagement and Influence. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7303-1279-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=hViuEAAAQBAJ.

- Fuchs, Dmitry; Fuchs, Ekaterina (2007). "Closed Geodesics on Regular Polyhedra". Moscow Mathematical Journal 7 (2): 265–279. doi:10.17323/1609-4514-2007-7-2-265-279. https://web.archive.org/web/20180304110822id_/http://www.ams.org:80/distribution/mmj/vol7-2-2007/fuchs.pdf.

- Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking. Macmillan Publishing. 1982. ISBN 978-0-02-065320-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=AKDgDQAAQBAJ.

- Gallardo, J.; Pérez-Illana, M.; Martín-González, N.; San Martín, C. (May 2021). "Adenovirus Structure: What Is New?". International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22 (10): 5240. doi:10.3390/ijms22105240. PMID 34063479.

- "A dynamic survey of graph labeling". Electronic Journal of Combinatorics 5: Dynamic Survey 6, 43 pp. (389 pp. in 18th ed.) (electronic). 1998. https://www.combinatorics.org/ojs/index.php/eljc/article/viewFile/DS6/pdf.

- Gailiunas, Paul (2023). "Kagome from Deltahedra". Bridges Conference Proceedings. Phoenix, Arizona: Tessellations Publishing. pp. 337–344.

- Gray, Hermann (2018). A History of Abstract Algebra: From Algebraic Equations to Modern Algebra. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-94772-3. ISBN 978-3-319-94772-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=gl1oDwAAQBAJ.

- Kunstformen der Natur. 1904. See here for an online book.

- Hart, George W. (1998). "Icosahedral Constructions". in Sarhangi, Reza. Bridges: Mathematical Connections in Art, Music, and Science. Arkansas City, Kansas: Gilliland Printing. http://t.archive.bridgesmathart.org/1998/bridges1998-195.pdf.

- Herrmann, Diane L.; Sally, Paul J. (2013). Number, Shape, & Symmetry: An Introduction to Number Theory, Geometry, and Group Theory. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-5464-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=b2fjR81h6yEC.

- The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1908. https://archive.org/details/thirteenbookseu03heibgoog/page/480.

- Herz-Fischler, Roger (2013). A Mathematical History of the Golden Number. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-15232-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=aYjXZJwLARQC.

- Hofmeister, H. (2004). "Fivefold Twinned Nanoparticles". Encyclopedia of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 3: 431–452.

- Hopkins, Brian (2004). "Hamiltonian paths on Platonic graphs". International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences 2004 (30): 1613–1616. doi:10.1155/S0161171204307118.

- Inchbald, Guy (2006). "Facetting Diagrams". The Mathematical Gazette 90 (518): 253–261. doi:10.1017/S0025557200179653.

- "Convex polyhedra with regular faces". Canadian Journal of Mathematics 18: 169–200. 1966. doi:10.4153/cjm-1966-021-8.

- Joyner, David (2008). Adventures in Group Theory: Rubik's Cube, Merlin's Machine, and Other Mathematical Toys (2nd ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9012-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=6an_DwAAQBAJ.

- Kappraff, Jay (1991). Connections: The Geometric Bridge Between Art and Science (2nd ed.). World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-281-139-4.

- Katz, E. A. (2006). "Fullerene Thin Films as Photovoltaic Material". in Sōga, Tetsuo. Nanostructured materials for solar energy conversion. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-52844-5.

- King, R. Bruce (2020). "Systematics of Atomic Orbital Hybridization of Coordination Polyhedra: Role of f Orbitals". Molecules 25 (14): 3113. doi:10.3390/molecules25143113. PMID 32650425.

- Kotschick, Dieter (2006). "The Topology and Combinatorics of Soccer Balls". American Scientist 94 (4): 350. doi:10.1511/2006.60.350. https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-topology-and-combinatorics-of-soccer-balls.

- Lectures on the ikosahedron and the solution of equations of the fifth degree. Courier Corporation. 1888. ISBN 978-0-486-49528-6. https://digital.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=math;cc=math;view=toc;subview=short;idno=03070001, Dover edition, translated from Klein, Felix (1884). Vorlesungen über das Ikosaeder und die Auflösung der Gleichungen vom fünften Grade. Teubner. https://archive.org/details/vorlesungenberd00kleigoog.

- Lawson, Kyle A.; Parish, James L.; Traub, Cynthia M.; Weyhaupt, Adam G. (2013). "Coloring graphs to classify simple closed geodesics on convex deltahedra". International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 89 (2): 123–139. doi:10.12732/ijpam.v89i2.1.

- The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number (1st trade paperback ed.). New York City: Broadway Books. 2003. ISBN 978-0-7679-0816-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=bUARfgWRH14C.

- MacLean, Kenneth J. M. (2007). A Geometric Analysis of the Platonic Solids and Other Semi-Regular Polyhedra. Loving Healing Press. ISBN 978-1-932690-99-6.

- Minas-Nerpel, Martina (2007). "A Demotic Inscribed Icosahedron from Dakhleh Oasis". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 93 (1): 137–148. doi:10.1177/030751330709300107.

- Popko, Edward (2012). Divided Spheres: Geodesics and the Orderly Subdivision of the Sphere. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-0429-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=WLAFlr1_2S4C.

- Pugh, Anthony (1976a). Polyhedra: A Visual Approach. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03056-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=IDDxpYQTR7kC.

- Rees, Elmer G. (2000). Notes on Geometry. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-61777-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=tmXvCAAAQBAJ.

- Rotman, Joseph (1998). Galois Theory. Universitext (2nd ed.). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0617-0. ISBN 978-1-4612-0617-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=0kHhBwAAQBAJ.

- Shavinina, Larisa V. (2013). The Routledge International Handbook of Innovation Education. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-38714-6.

- Seidel, J. J. (1991). Geometry and Combinatorics. Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-4832-6800-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=brziBQAAQBAJ.

- Senechal, Marjorie (1989). "A Brief Introduction to Tilings". in Jarić, Marko. Introduction to the Mathematics of Quasicrystals. Academic Press. p. 12. https://books.google.com/books?id=OToVjZW9CKMC.

- Silvester, John R. (2001). Geometry: Ancient and Modern. Oxford University Publisher.

- Simmons, George F. (2007). Calculus Gems: Brief Lives and Memorable Mathematics. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-561-4.

- Smith, David E. (1958). History of Mathematics. 2. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20430-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=uTytJGnTf1kC.

- "New Ligand Platforms Featuring Boron-Rich Clusters as Organomimetic Sbstituents". Pure and Applied Chemistry 85 (5): 903–919. 2013. doi:10.1351/PAC-CON-13-01-13. PMID 24311823.

- Stillwell, John (2005). "Transformations". The Four Pillars of Geometry. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer. doi:10.1007/0-387-29052-4. ISBN 978-0-387-29052-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=I1QPQic_PxwC.

- Strauss, James H.; Strauss, Ellen G. (2008). "The Structure of Viruses". Viruses and Human Disease. Elsevier. pp. 35–62. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-373741-0.50005-2. ISBN 978-0-12-373741-0.

- Sutton, Daud (2002). Platonic & Archimedean Solids. Wooden Books. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-8027-1386-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=vgo7bTxDmIsC.

- Steeb, Willi-hans; Hardy, Yorick; Tanski, Igor (2012) (in en). Problems And Solutions For Groups, Lie Groups, Lie Algebras With Applications. World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-981-310-411-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=UdI7DQAAQBAJ.

- Timofeenko, A. V. (2010). "Junction of Non-composite Polyhedra". St. Petersburg Mathematical Journal 21 (3): 483–512. doi:10.1090/S1061-0022-10-01105-2. https://www.ams.org/journals/spmj/2010-21-03/S1061-0022-10-01105-2/S1061-0022-10-01105-2.pdf.

- Tsuruta, Naoya (2024). "ICGG 2024 - Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Geometry and Graphics". in Takenouchi, Kazuki. 1. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-71225-8. ISBN 978-3-031-71225-8.

- Verheyen, H. F. (1989). "The complete set of Jitterbug transformers and the analysis of their motion". Computers and Mathematics with Applications 17 (1–3): 203–250. doi:10.1016/0898-1221(89)90160-0.

- Walter, Steurer; Deloudi, Sofia (2009). Crystallography of Quasicrystals: Concepts, Methods and Structures. Springer Series in Materials Science. 126. p. 50. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01899-2. ISBN 978-3-642-01898-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=nVx-tu596twC&pg=PA50.

- Wells, David (1991). The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry. London: Penguin.

- Wenninger, Magnus J. (1971). Polyhedron Models. Cambridge University Press.

- Whyte, L. L. (1952). "Unique arrangements of points on a sphere". The American Mathematical Monthly 59 (9): 606–611. doi:10.1080/00029890.1952.11988207.

- Yackel, Carolyn (26–30 July 2013). "Proceedings of Bridges 2009: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture". Banff, Alberta, Canada. pp. 123–130. ISBN 978-0-96652-020-0.

External links

- Klitzing, Richard. "3D convex uniform polyhedra x3o5o – ike". https://bendwavy.org/klitzing/dimensions/polyhedra.htm.

- Hartley, Michael. "Dr Mike's Math Games for Kids". http://www.dr-mikes-math-games-for-kids.com/polyhedral-nets.html?net=PKYcLAHcKk9lKCGWdoeJHvnDe7jSJyKXIghPYlKcV5PxkeWqGqwmeoyXUilmvzkXsQnxEoduPHUYFqOf20B8EwLz8CufLOUuc4N5&name=Icosahedron#applet.

- K.J.M. MacLean, A Geometric Analysis of the Five Platonic Solids and Other Semi-Regular Polyhedra

- Virtual Reality Polyhedra The Encyclopedia of Polyhedra

- Tulane.edu A discussion of viral structure and the icosahedron

- Origami Polyhedra – Models made with Modular Origami

- Video of icosahedral mirror sculpture

- [1] Principle of virus architecture

Fundamental convex regular and uniform polytopes in dimensions 2–10

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | An | Bn | I2(p) / Dn | E6 / E7 / E8 / F4 / G2 | Hn | |||||||

| Regular polygon | Triangle | Square | p-gon | Hexagon | Pentagon | |||||||

| Uniform polyhedron | Tetrahedron | Octahedron • Cube | Demicube | Dodecahedron • Icosahedron | ||||||||

| Uniform 4-polytope | 5-cell | 16-cell • Tesseract | Demitesseract | 24-cell | 120-cell • 600-cell | |||||||

| Uniform 5-polytope | 5-simplex | 5-orthoplex • 5-cube | 5-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform 6-polytope | 6-simplex | 6-orthoplex • 6-cube | 6-demicube | 122 • 221 | ||||||||

| Uniform 7-polytope | 7-simplex | 7-orthoplex • 7-cube | 7-demicube | 132 • 231 • 321 | ||||||||

| Uniform 8-polytope | 8-simplex | 8-orthoplex • 8-cube | 8-demicube | 142 • 241 • 421 | ||||||||

| Uniform 9-polytope | 9-simplex | 9-orthoplex • 9-cube | 9-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform 10-polytope | 10-simplex | 10-orthoplex • 10-cube | 10-demicube | |||||||||

| Uniform n-polytope | n-simplex | n-orthoplex • n-cube | n-demicube | 1k2 • 2k1 • k21 | n-pentagonal polytope | |||||||

| Topics: Polytope families • Regular polytope • List of regular polytopes and compounds | ||||||||||||

| Notable stellations of the icosahedron | |||||||||

| Regular | Uniform duals | Regular compounds | Regular star | Others | |||||

| (Convex) icosahedron | Small triambic icosahedron | Medial triambic icosahedron | Great triambic icosahedron | Compound of five octahedra | Compound of five tetrahedra | Compound of ten tetrahedra | Great icosahedron | Excavated dodecahedron | Final stellation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| The stellation process on the icosahedron creates a number of related polyhedra and compounds with icosahedral symmetry. | |||||||||

|