Chemistry:Tagatose

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

D-lyxo-Hex-2-ulose[1]

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(3S,4S,5R)-1,3,4,5,6-Pentahydroxy-hexan-2-one | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H12O6 | |

| Molar mass | 180.16 g/mol |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Melting point | 133 to 135 °C (271 to 275 °F; 406 to 408 K) |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | [1] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Tagatose is a hexose monosaccharide. It is found in small quantities in a variety of foods, and has attracted attention as an alternative sweetener.[2] It is often found in dairy products, because it is formed when milk is heated. It is similar in texture and appearance to sucrose (table sugar)[3]:215 and is 92% as sweet,[3]:198 but with only 38% of the calories.[3]:209 Tagatose is generally recognized as safe by the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization, and has been since 2001. Since it is metabolized differently from sucrose, tagatose has a minimal effect on blood glucose and insulin levels. Tagatose is also approved as a tooth-friendly ingredient for dental products. Consumption of more than about 30 grams of tagatose in a dose may cause gastric disturbance in some people, as it is mostly processed in the large intestine, similar to soluble fiber.[3]:214

Production

Tagatose is a natural sweetener present in only small amounts in fruits, cacao, and dairy products. Starting with lactose, which is hydrolyzed to glucose and galactose, tagatose can then be produced commercially from the resulting galactose. The galactose is isomerized under alkaline conditions to D-tagatose by calcium hydroxide. Under conditions employed for a Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction, the tetra-O-benzyl galactose converts to tetra-O-benzyltagatose. Hydrogenolysis removes the four benzyl groups, leaving tagatose.[4]

Tagatose also can be made from starch or maltodextrin via an enzymatic cascade reaction.[5] The process to produce tagatose powder may soon involve spray drying.[6]

Development as a sweetener

D-Tagatose was proposed as a sweetener by Gilbert Levin, after unsuccessful attempts to market L-glucose for that application. He patented an inexpensive method to make tagatose in 1988.[7] The low food calorie contents is due to its resemblance to L-fructose.[8]

Safety and function

The United States Food and Drug Administration approved tagatose as a food additive in October 2003 and designated it as generally recognized as safe. The Korea Food & Drug Administration approved tagatose as health functional food for antihyperglycemic effect. European Food Safety Authority approved tagatose as novel food and novel food ingredient. New Zealand, and Australia have also approved tagatose for human consumption.[9]

Characteristics

Functional characteristics

Low glycemic index

Tagatose has very similar sweetness to sugar while its glycemic index (GI 3) is very low. GI is a measure of the effects of carbohydrates in food on blood sugar levels. It estimates how much each gram of available carbohydrate (total carbohydrate minus fiber) in a food raises a person's blood glucose level following consumption of the food, relative to consumption of glucose. Glucose has a glycemic index of 100, by definition, and other foods have lower glycemic index. Sucrose has a GI of 68, fructose is 24, and tagatose has very low GI compared with other sweeteners.

High blood glucose levels or repeated glycemic "spikes" following a meal may promote type 2 diabetes by increasing systemic glycative stress other oxidative stress to the vasculature and also by the direct increase in insulin levels,[10] while individuals who followed a low-GI diet over many years were at a significantly lower risk for developing both type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and age-related macular degeneration than others.[11]

Antihyperglycemic effect

The Korea Food & Drug Administration approved the safety and function of tagatose for controlling postprandial blood glucose level. Tagatose reduces blood glucose level in the liver by promoting glucokinase activity which promotes transfer of glucose to glycogen. It also inhibits digestive enzymes and degradation of carbohydrates in small intestine which result in inhibition of carbohydrate absorption in the body. Antihyperglycemic function is important for those with both type 1 diabetes mellitus and type 2 diabetes mellitus especially because diabetes is continuously growing and spreading to the younger generation. US$92 billion was spent for diabetes medication in 2008 in the US, and US$50 billion is paid in China per year.[12]

Physical characteristics

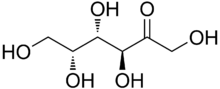

Tagatose is a white crystalline powder with a molecular formula of C6H12O6 with a molecular weight of 180.16 g/mol. Active maillard reaction of tagatose enhances flavor and brown coloring performance and is usually used for baking, cooking and with high-intensity sweeteners to mask their bitter aftertaste.

Marketing

In 1996, MD/Arla Foods acquired the rights to production from Spherix, the American license holder. In the following years, no products were brought to market by MD/Arla Foods, so Spherix brought them before a US Court of Arbitration for showing insufficient interest in bringing the product to market. The companies settled, with MD/Arla Foods agreeing to pay longer-term royalties to Spherix and Spherix agreeing to not take further action.

In March 2006, SweetGredients (a joint venture company of Arla Foods and Nordzucker AG) decided to shelve the tagatose project. SweetGredients was the only worldwide producer of tagatose. While progress had been made in creating a market for this innovative sweetener, it had not been possible to identify a large enough potential to justify continued investments, and SweetGredients decided to close down the manufacturing of tagatose in Nordstemmen, Germany.

In 2006, the Belgian company Nutrilab NV took over the Arla (SweetGredients) stocks and project, and set up an 800-tons-per-year production site in Italy with an enzymatic process from whey for D-tagatose with the brand name Nutrilatose. This process was said to be considerably cheaper than the chemical process previously used by Arla.[13] In 2007 Damhert N.V., the mother company of Nutrilab, released the tagatose-based sweetener Tagatesse under its own brand name, along with some other products (jams and some chocolate-based products) using tagatose [14] in the Benelux and France. Damhert's marketing strategy was to gradually build up the market for tagatose by introducing it to small and medium-sized companies. In 2013, 30% of the profits of Damhert were reported to come from tagatose, and they were preparing to scale up their production capacity to 2,500 tons per year.[13] It was also reported in February 2013 that PepsiCo and Yoplait were interested in using tagatose. Damhert were considering in the longer term building a 10,000-tons-per-annum tagatose plant in Belgium but needed to find the capital to build such a plant.[15]

One of the major producers for D-tagatose was CJ Cheiljedang, located in South Korea, under the brand name "Baeksul Tagatose". In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved CJ Cheiljedang’s enzyme conversion tagatose production as a food additive and designated it as generally recognized as safe.[16]

References

- ↑ iupac.qmul.ac.uk/2carb/10.html

- ↑ Mu, Wanmeng; Hassanin, Hinawi A. M.; Zhou, Leon; Jiang, Bo (2018). "Chemistry Behind Rare Sugars and Bioprocessing". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 66 (51): 13343–13345. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06293. PMID 30543101.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Alternative sweeteners. Nabors, Lyn O'Brien, 1943- (4th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 2012. ISBN 978-1-4398-4615-5. OCLC 760056415. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/760056415.

- ↑ Frihed, Tobias Gylling; Bols, Mikael; Pedersen, Christian Marcus (2015). "Synthesis of l-Hexoses". Chemical Reviews 115 (9): 3615–3676. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00104. PMID 25893557.

- ↑ "D-tagatose produced via novel enzymatic cascade". https://www.cfsanappsexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/?set=GRASNotices&id=977&sort=GRN_No&order=DESC&startrow=1&type=basic&search=tagatose.

- ↑ Campbell, Heather R.; Alsharif, Fahd M.; Marsac, Patrick J.; Lodder, Robert A. (2020). "The Development of a Novel Pharmaceutical Formulation of D-Tagatose for Spray-Drying". Journal of Pharmaceutical Innovation 17: 1–13. doi:10.1007/s12247-020-09507-4.

- ↑ A Natural Way to Stay Sweet, NASA, https://spinoff.nasa.gov/Spinoff2004/ch_4.html, retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ↑ Evan Ratliff (Nov 2003). "Hitting the Sweet Spot". Wired (Wired.com). https://www.wired.com/wired/archive/11.11/newsugar.html.

- ↑ Tandel, KirtidaR (2011-10-01). "Sugar substitutes: Health controversy over perceived benefits" (in en). Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics 2 (4): 236–243. doi:10.4103/0976-500x.85936. PMID 22025850. PMC 3198517. http://www.jpharmacol.com/text.asp?2011/2/4/236/85936.

- ↑ Temelkova-Kurktschiev, T. S.; Koehler, C.; Henkel, E.; Leonhardt, W.; Fuecker, K.; Hanefeld, M. (2000). "Postchallenge plasma glucose and glycemic spikes are more strongly associated with atherosclerosis than fasting glucose or HbA1c level". Diabetes Care 23 (12): 1830–1834. doi:10.2337/diacare.23.12.1830. PMID 11128361.

- ↑ Chiu, Chung-Jung; Liu, Simin; Willett, Walter C.; Wolever, Thomas MS; Brand-Miller, Jennie C.; Barclay, Alan W.; Taylor, Allen (2011). "Informing food choices and health outcomes by use of the dietary glycemic index". Nutrition Reviews 69 (4): 231–242. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00382.x. PMID 21457267.

- ↑ WHO report, 13Nov 2009

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Goodwin, Diana (20 February 2013) The sweet taste of success Flanders Today, Retrieved 27 February 2013

- ↑ (2013) Tagatose Damhurt Nutrition web page, Retrieved 28 February 2013

- ↑ Grommen, Stefan (5 February 2013) Pepsi en Yoplait reikhalzen naar Limburgse zoetstof (Pepsi and Yoplait would like to use Limburg sweetener) (In Dutch) Het Laatste Nieuws, Retrieved 28 February 2013

- ↑ "Enforcement Reports". http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/fcn/fcnDetailNavigation.cfm?rpt=grasListing&id=352.

External links

- Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization recommendation

- Calorie Control Council—consumer info from artificial sweetener manufacturers organization

- MD/Arla Foods settlement with Spherix

|