Biology:Acarbose

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Glucobay, Precose, Prandase |

| Other names | (2R,3R,4R,5S,6R)-5-{[(2R,3R,4R,5S,6R)-5- {[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4-dihydroxy-6-methyl- 5-{[(1S,4R,5S,6S)-4,5,6-trihydroxy-3- (hydroxymethyl)cyclohex-2-en-1-yl]amino} tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl]oxy}-3,4-dihydroxy- 6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl]oxy}- 6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2,3,4-triol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a696015 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Extremely low |

| Metabolism | Gastrointestinal tract

glucosidase maltogenic alpha-amylase and cyclomaltodextrinase from gut microbiome |

| Elimination half-life | 2 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (less than 2%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C25H43NO18 |

| Molar mass | 645.608 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Acarbose (INN)[1][2] is an anti-diabetic drug used to treat diabetes mellitus type 2 and, in some countries, prediabetes. It is a generic sold in Europe and China as Glucobay (Bayer AG), in North America as Precose (Bayer Pharmaceuticals), and in Canada as Prandase (Bayer AG).

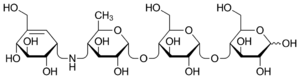

Acarbose is a starch blocker. It works by inhibiting alpha glucosidase, an intestinal enzyme that releases glucose from larger carbohydrates such as starch and sucrose. It is composed of an acarviosin moiety with a maltose at the reducing terminus. It can be degraded by a number of gut bacteria.[3]

Acarbose is cheap and popular in China, but not in the U.S. One physician explains that use in the U.S. is limited because it is not potent enough to justify the side effects of diarrhea and flatulence.[4] However, a large study concluded in 2013 that "acarbose is effective, safe and well tolerated in a large cohort of Asian patients with type 2 diabetes."[5] A possible explanation for the differing opinions is an observation that acarbose is significantly more effective in patients eating a relatively high carbohydrate Eastern diet.[6]

Medical uses

Dosing

Since acarbose prevents the digestion of complex carbohydrates, the drug should be taken at the start of main meals (taken with first bite of meal).[7] Moreover, the amount of complex carbohydrates in the meal will determine the effectiveness of acarbose in decreasing postprandial hyperglycemia. Adults may take doses of 25 mg 3 times daily, increasing to 100 mg 3 times a day. However the maximum dose per day is 600 mg.[citation needed]

Efficacy

In type II diabetic patients, acarbose averages an absolute decrease of 0.8 percentage points in HbA1c, which is a decrease of about 10% in typical HbA1c values in diabetes studies.[8] Individuals with higher baseline levels show higher reductions, about an 0.12% additional decrease for each point of baseline HbA1c.[8] Its effect on postprandial glucose, but not on HbA1c, scales with dose.[8] Among diabetic patients, acarbose may help reduce the damage done to blood vessels and kidneys by reducing glucose levels.[8]

A Cochrane systematic review assessed the effect of alpha-glucosidase inhibitors in people with prediabetes, defined as impaired glucose tolerance, impaired fasting blood glucose, elevated glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).[9] It was found that acarbose reduced the incidence of diabetes mellitus type 2 when compared to placebo, however there was no conclusive evidence that acarbose, when compared to diet and exercise, metformin, placebo, or no intervention, improved all-cause mortality, reduced or increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, serious or non-serious adverse events, non-fatal stroke, congestive heart failure, or non-fatal myocardial infarction.[9]

Combination therapy

The combination of acarbose with metformin results in greater reductions of HbA1c, fasting blood glucose and post-prandial glucose than either agent alone.[10]

Adverse effects

Since acarbose prevents the degradation of complex carbohydrates into glucose, some carbohydrate will remain in the intestine and be delivered to the colon. In the colon, bacteria digest (ferment) the complex carbohydrates, causing gastrointestinal side-effects such as flatulence (78% of patients) and diarrhea (14% of patients). Since these effects are dose-related, in general it is advised to start with a low dose and gradually increase the dose to the desired amount. One study found that gastrointestinal side effects decreased significantly (from 50% to 15%) over 24 weeks, even on constant dosing.[11] Sucrose is more likely to trigger GI side effects compared to starch.[8]

If a patient using acarbose has a bout of hypoglycemia, the patient must eat something containing monosaccharides, such as glucose tablets or gel (GlucoBurst, Insta-Glucose, Glutose, Level One) and a doctor should be called. Because acarbose blocks the breakdown of table sugar and other complex sugars, fruit juice or starchy foods will not effectively reverse a hypoglycemic episode in a patient taking acarbose.[12] Acarbose by itself carries minimal risk of hypoglycemia.[8]

Acarbose is associated with very rare elevated transaminases (19 out of 500,000).[8] Even rarer cases of hepatitis has been reported with acarbose use. It usually goes away when the medicine is stopped. Liver enzymes should be checked before and during use of this medicine as a precaution.[13] A 2016 meta-analysis confirms that alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, including acarbose, have a statistically significant link to elevated transaminase levels.[14]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Acarbose inhibits enzymes (glycoside hydrolases) needed to digest carbohydrates, specifically, alpha-glucosidase enzymes in the brush border of the small intestines, and pancreatic alpha-amylase. It locks up the enzymes by mimicking the transition state of the substrate with its amine linkage.[15] However, bacterial alpha-amylases from gut microbiome are able to degrade acarbose.[16][17][18]

Pancreatic alpha-amylase hydrolyzes complex starches to oligosaccharides in the lumen of the small intestine, whereas the membrane-bound intestinal alpha-glucosidases hydrolyze oligosaccharides, trisaccharides, and disaccharides to glucose and other monosaccharides in the small intestine. Inhibition of these enzyme systems reduces the rate of digestion of complex carbohydrates. Less glucose is absorbed because the carbohydrates are not broken down into glucose molecules. In diabetic patients, the short-term effect of these drug therapies is to decrease current blood glucose levels; the long-term effect is a reduction in HbA1c level.[19]

Metabolism

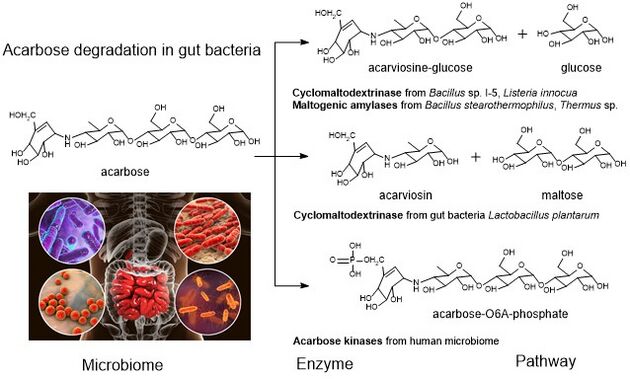

Acarbose degradation is the unique feature of glycoside hydrolases in gut microbiota, acarbose degrading glucosidase, which hydrolyze acarbose into an acarviosine-glucose and glucose.[18] Human enzymes do transform acarbose: the pancreatic alpha-amylase is able to perform a rearrangement reaction, moving the glucose unit in the "tail" maltose to the "head" of the molecule. Analog drugs with the "tail" glucose removed or flipped to an α(1-6) linkage resist this transformation.[15]

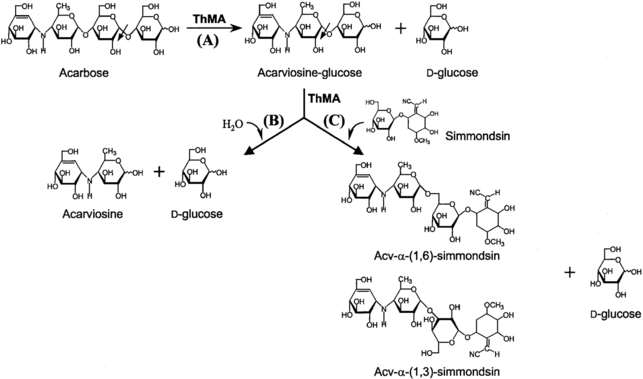

It has been reported that the maltogenic alpha-amylase from Thermus sp. IM6501 (ThMA) and a cyclodextrinase (CDase) from Streptococcus pyogenes could hydrolyse acarbose to glucose and acarviosine-glucose, ThMA can further hydrolyze acarviosine-glucose into acarviosin and glucose.[20][21] A cyclomaltodextrinase (CDase) from gut bacteria Lactobacillus plantarum degraded acarbose via two different modes of action to produce maltose and acarviosin, as well as glucose and acarviosine-glucose, suggest that acarbose resistance is caused by the human microbiome.[3] The microbiome-derived acarbose kinases are also specific to phosphorylate and inactivate acarbose.[22] The molecular modeling showed the interaction between gut bacterial acarbose degrading glucosidase and human α-amylase.[23]

Natural distribution

In nature, acarbose is synthesized by soil bacteria Actinoplanes sp through its precursor valienamine.[24] And acarbose is also degraded by gut bacteria Lactobacillus plantarum and soil bacteria Thermus sp by acarbose degrading glucosidases.

In molecular biology

Acarbose is described chemically as a pseudotetrasaccharide,[25] specifically a maltotetraose mimic inhibitor. As an inhibitor that mimics some natural substrates, it is useful for elucidating the structure of sugar-digesting enzymes, by binding into the same pocket.[26]

Research

In human T2DM patients, acarbose reduces total triglyceride levels.[27] Acarbose has a similar effect in non-T2DM patients with isolated familial hypertriglyceridemia.[8]

In smaller samples of healthy human volunteers, acarbose increases postprandial GLP-1 levels.[8]

In studies conducted by three independent laboratories by the US National Institute on Aging's intervention testing programme, acarbose was shown to extend the lifespan of female mice by 5% and of male mice by 22%.[28][29]

References

- ↑ The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. 1990. pp. 1–. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-2085-3. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ↑ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances. Recommended International Nonproprietary Names (Rec. INN): List 19". World Health Organization. 1979. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/druginformation/innlists/RL19.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Functional expression and enzymatic characterization of Lactobacillus plantarum cyclomaltodextrinase catalyzing novel acarbose hydrolysis". Journal of Microbiology 56 (2): 113–118. February 2018. doi:10.1007/s12275-018-7551-3. PMID 29392561.

- ↑ "China's Thirst for New Diabetes Drugs Threatens Bayer's Lead". Bloomberg Business Week. 21 November 2011. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2011-11-21/china-s-thirst-for-new-diabetes-drugs-threatens-bayer-s-lead.html.

- ↑ "A multinational, observational study to investigate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of acarbose as add-on or monotherapy in a range of patients: the Gluco VIP study". Clinical Drug Investigation 33 (4): 263–274. April 2013. doi:10.1007/s40261-013-0063-3. PMID 23435929.

- ↑ "Comparison of the hypoglycemic effect of acarbose monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus consuming an Eastern or Western diet: a systematic meta-analysis". Clinical Therapeutics 35 (6): 880–899. June 2013. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.03.020. PMID 23602502.

- ↑ "The Effect of the Timing and the Administration of Acarbose on Postprandial Hyperglycaemia". Diabetic Medicine 12 (11): 979–984. November 1995. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.1995.tb00409.x. PMID 8582130.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 "Acarbose: safe and effective for lowering postprandial hyperglycaemia and improving cardiovascular outcomes". Open Heart 2 (1): e000327. 2015. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2015-000327. PMID 26512331.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in people at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018 (12): CD005061. December 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005061.pub3. PMID 30592787.

- ↑ "Considerations when using alpha-glucosidase inhibitors in the treatment of type 2 diabetes". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 20 (18): 2229–2235. December 2019. doi:10.1080/14656566.2019.1672660. PMID 31593486.

- ↑ "Efficacy of 24-week monotherapy with acarbose, metformin, or placebo in dietary-treated NIDDM patients: the Essen-II Study". The American Journal of Medicine 103 (6): 483–490. December 1997. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00252-0. PMID 9428831.

- ↑ "Acarbose". MedlinePlus Drug Information. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a696015.html.

- ↑ "Acarbose: hepatitis: France, Spain". WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter. 1999. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js2268e/2.html#Js2268e.2.1.

- ↑ Zhang, Longhao; Chen, Qiyan; Li, Ling; Kwong, Joey S. W.; Jia, Pengli; Zhao, Pujing; Wang, Wen; Zhou, Xu et al. (6 September 2016). "Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors and hepatotoxicity in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Scientific Reports 6 (1): 32649. doi:10.1038/srep32649. PMID 27596383. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...632649Z.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Acarbose rearrangement mechanism implied by the kinetic and structural analysis of human pancreatic alpha-amylase in complex with analogues and their elongated counterparts". Biochemistry 44 (9): 3347–3357. March 2005. doi:10.1021/bi048334e. PMID 15736945.

- ↑ "Transglycosylation reactions of Bacillus stearothermophilus maltogenic amylase with acarbose and various acceptors". Carbohydrate Research 313 (3–4): 235–246. December 1998. doi:10.1016/S0008-6215(98)00276-6. PMID 10209866.

- ↑ "Modulation of hydrolysis and transglycosylation activity of Thermus maltogenic amylase by combinatorial saturation mutagenesis". Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 18 (8): 1401–1407. August 2008. PMID 18756100. https://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO200835054207140.page.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Modes of action of acarbose hydrolysis and transglycosylation catalyzed by a thermostable maltogenic amylase, the gene for which was cloned from a Thermus strain". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 65 (4): 1644–1651. April 1999. doi:10.1128/AEM.65.4.1644-1651.1999. PMID 10103262. Bibcode: 1999ApEnM..65.1644K.

- ↑ Drug Therapy in Nursing, 2nd Edition.

- ↑ "Functional expression and enzymatic characterization of cyclomaltodextrinase from Streptococcus pyogenes". Korean Journal of Microbiology 53 (3): 208–215. 2017. doi:10.7845/kjm.2017.7062. ISSN 0440-2413.

- ↑ "Acarviosine-simmondsin, a novel compound obtained from acarviosine-glucose and simmondsin by Thermus maltogenic amylase and its in vivo effect on food intake and hyperglycemia". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 67 (3): 532–539. March 2003. doi:10.1271/bbb.67.532. PMID 12723600.

- ↑ "The human microbiome encodes resistance to the antidiabetic drug acarbose". Nature 600 (7887): 110–115. December 2021. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04091-0. PMID 34819672. Bibcode: 2021Natur.600..110B.

- ↑ "Function and Tertiary- and Quaternary-structure of Cyclodextrin-hydrolyzing Enzymes (CDase), a Group of Multisubstrate Specific Enzymes Belonging to the α-Amylase Family" (in en). Journal of Applied Glycoscience 53 (1): 35–44. 2006. doi:10.5458/jag.53.35. ISSN 1344-7882. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jag/53/1/53_1_35/_article.

- ↑ "Complete biosynthetic pathway to the antidiabetic drug acarbose". Nature Communications 13 (1): 3455. June 2022. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31232-4. PMID 35705566. Bibcode: 2022NatCo..13.3455T.

- ↑ "The 'pair of sugar tongs' site on the non-catalytic domain C of barley alpha-amylase participates in substrate binding and activity". The FEBS Journal 274 (19): 5055–5067. October 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06024.x. PMID 17803687.

- ↑ "Structure-function analysis of silkworm sucrose hydrolase uncovers the mechanism of substrate specificity in GH13 subfamily 17 exo-α-glucosidases". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 295 (26): 8784–8797. June 2020. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA120.013595. PMID 32381508.

- ↑ Yousefi, Mohsen; Fateh, Sahand Tehrani; Nikbaf-Shandiz, Mahlagha; Gholami, Fatemeh; Rastgoo, Samira; Bagher, Reza; Khadem, Alireza; Shiraseb, Farideh et al. (22 November 2023). "The effect of acarbose on lipid profiles in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology 24 (1): 65. doi:10.1186/s40360-023-00706-6. PMID 37990256.

- ↑ "Acarbose, 17-α-estradiol, and nordihydroguaiaretic acid extend mouse lifespan preferentially in males". Aging Cell 13 (2): 273–282. April 2014. doi:10.1111/acel.12170. PMID 24245565.

- ↑ "Testing drug combinations to slow aging". Pathobiology of Aging & Age Related Diseases 8 (1): 1407203. 2017. doi:10.1080/20010001.2017.1407203. PMID 29291036.

External links

- "Acarbose". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/acarbose.

- "Probing the Pancreas" - by Craig D. Reid, Ph.D. (US FDA Consumer Article)

|