Chemistry:Dihydroxyacetone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

1,3-Dihydroxypropan-2-one | |

| Other names

1,3-Dihydroxypropanone

Dihydroxyacetone DHA Glycerone | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties[1] | |

| C3H6O3 | |

| Molar mass | 90.078 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 89 to 91 °C (192 to 196 °F; 362 to 364 K) |

| Hazards[2] | |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | WARNING |

| H319 | |

| P264, P280, P305+351+338, P337+313 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

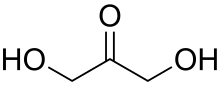

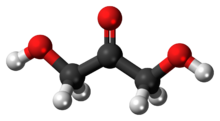

Dihydroxyacetone (/ˌdaɪhaɪˌdrɒksiˈæsɪtoʊn/ (![]() listen); DHA), also known as glycerone, is a simple saccharide (a triose) with formula C3H6O3.

listen); DHA), also known as glycerone, is a simple saccharide (a triose) with formula C3H6O3.

DHA is primarily used as an ingredient in sunless tanning products. It is often derived from plant sources such as sugar beets and sugar cane, and by the fermentation of glycerin.

Chemistry

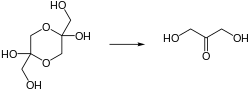

DHA is a hygroscopic white crystalline powder. It has a sweet cooling taste and a characteristic odor. It is the simplest of all ketoses and has no chiral center. The normal form is a dimer (2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)-1,4-dioxane-2,5-diol). The dimer slowly dissolves in water,[3] whereupon it converts to the monomer. These solutions are stable at pH's between 4 and 6. In more basic solution, it degrades to brown product.[4]

This skin browning effect is attributed to a Maillard reaction. DHA condenses with the amino acid residues in the protein keratin, the major component of the skin surface. When injected, no pigmentation occurs, consistent with a role for oxygen in color development.[4] The resulting pigments, which can be removed by abrasion, are called melanoidins. These are similar in coloration to melanin, the natural substance in the deeper skin layers which brown or "tan" from exposure to UV rays.

Preparation

DHA may be prepared, along with glyceraldehyde, by the mild oxidation of glycerol, for example with hydrogen peroxide and a ferrous salt as catalyst. It can also be prepared in high yield and selectivity at room temperature from glycerol using cationic palladium-based catalysts with oxygen, air or benzoquinone acting as co-oxidants.[5][6][7] Glyceraldehyde is a structural isomer of dihydroxyacetone.

Biochemistry

Its phosphorylated form, dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), takes part in glycolysis, and it is an intermediate product of fructose metabolism.

History

DHA was first recognized as a skin coloring agent by German scientists in the 1920s. Through its use in the X-ray process, it was noted as causing the skin surface to turn brown when spilled.

In the 1950s, Eva Wittgenstein at the University of Cincinnati did further research with dihydroxyacetone.[8][9][10][11] Her studies involved using DHA as an oral drug for assisting children with glycogen storage disease. The children received large doses of DHA by mouth, and sometimes spat or spilled the substance onto their skin. Healthcare workers noticed that the skin turned brown after a few hours of DHA exposure. Wittgenstein continued to experiment with DHA, painting liquid solutions of it onto her own skin. She was able to consistently reproduce the pigmentation effect, and noted that DHA did not appear to penetrate beyond the stratum corneum, or dead skin surface layer (the FDA eventually concluded this is not entirely true[12]). Research then continued on DHA's skin coloring effect in relation to treatment for patients with vitiligo.

Winemaking

Both acetic acid bacteria Acetobacter aceti and Gluconobacter oxydans use glycerol as a carbon source to form dihydroxyacetone. DHA is formed by ketogenesis of glycerol.[13] It can affect the sensory quality of the wine with sweet/etherish properties. DHA can also react with proline to produce a "crust-like" aroma.[13][14][15] Dihydroxyacetone can affect the anti-microbial activity in wine, as it has the ability to bind SO2.[16]

Sunless tanning

Coppertone introduced the first consumer sunless tanning lotion into the marketplace in the 1960s. This product was called "Quick Tan" or "QT". It was sold as an overnight tanning agent, and other companies followed suit with similar products. Consumers soon tired of this product due to unattractive results such as orange palms, streaking and poor coloration. Because of the QT experience, many people still associate sunless tanning with fake-looking orange tans.[citation needed]

In the 1970s the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) added DHA permanently to their list of approved cosmetic ingredients.[17]

By the 1980s, new sunless tanning formulations appeared on the market and refinements in the DHA manufacturing process created products that produced a more natural looking color and better fading. Consumer concerns surrounding damage associated with UV tanning options spurred further popularity of sunless tanning products as an alternative to UV tanning. Dozens of brands appeared on drugstore shelves, in numerous formulations.[citation needed]

Today, DHA is the main active ingredient in many sunless tanning skincare preparations. Lotion manufacturers also produce a wide variety of sunless tanning preparations that replace DHA with natural bronzing agents such as black walnut shell. DHA may be used alone or combined with other tanning components such as erythrulose. DHA is considered the most effective sun-free tanning additive.[citation needed]

Sunless tanning products contain DHA in concentrations ranging from 1% to 20%. Most drugstore products range from 3% to 5%, with professional products ranging from 5% to 20%. The percentages correspond with the product coloration levels from light to dark. Lighter products are more beginner-friendly, but may require multiple coats to produce the desired color depth. Darker products produce a dark tan in one coat, but are also more prone to streaking, unevenness, or off-color tones. The artificial tan takes 2 to 4 hours to begin appearing on the skin surface, and will continue to darken for 24 to 72 hours, depending on formulation type.[citation needed]

Once the darkening effect has occurred, the tan will not sweat off or wash away with soap or water. It will fade gradually over 3 to 10 days. Exfoliation, prolonged water submersion, or heavy sweating can lighten the tan, as these all contribute to rapid dead skin cell exfoliation (the dead skin cells are the tinted portion of the sunless tan).[citation needed]

Current sunless tanners are formulated into sprays, lotions, gels, mousses, and cosmetic wipes. Professional applied products include spray tanning booths, airbrush tan applications, and hand applied lotions, gels, mousses and wipes.[citation needed]

References

- ↑ Weast, Robert C., ed (1981). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (62nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. C-74. ISBN 0-8493-0462-8..

- ↑ HSNO Chemical Classification Information Database, New Zealand Environmental Risk Management Authority, http://www.epa.govt.nz/search-databases/Pages/ccid-details.aspx?SubstanceID=11687, retrieved 2009-09-03

- ↑ Budavari, Susan, ed. (1996), An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (12th ed.), Merck, ISBN 0911910123, 3225

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Levy, Stanley B. (1992). "Dihydroxyacetone-containing sunless or self-tanning lotions". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 27 (6): 989–993. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70300-5. PMID 1479107.

- ↑ Painter, Ron M.; Pearson, David M.; Waymouth, Robert M. (2010). "Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Glycerol to Dihydroxyacetone". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 49 (49): 9456–9. doi:10.1002/anie.201004063. PMID 21031380.

- ↑ Chung, Kevin; Banik, Steven M.; De Crisci, Antonio G.; Pearson, David M.; Blake, Timothy R.; Olsson, Johan V.; Ingram, Andrew J.; Zare, Richard N. et al. (2013). "Chemoselective Pd-Catalyzed Oxidation of Polyols: Synthetic Scope and Mechanistic Studies". Journal of the American Chemical Society 135 (20): 7593–602. doi:10.1021/ja4008694. PMID 23659308.

- ↑ De Crisci, Antonio G.; Chung, Kevin; Oliver, Allen G.; Solis-Ibarra, Diego; Waymouth, Robert M. (2013). "Chemoselective Oxidation of Polyols with Chiral Palladium Catalysts". Organometallics 32 (7): 2257–66. doi:10.1021/om4001549.

- ↑ "What's that stuff?". Chemical & Engineering News 78 (24): 46. 12 June 2000. doi:10.1021/cen-v078n024.p046. http://pubs.acs.org/cen/whatstuff/stuff/7824scit2.html.

- ↑ Wittgenstein, Eva; Guest, G M (1961). "Biochemical Effects of Dihydroxyacetone". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 37 (5): 421–6. doi:10.1038/jid.1961.137. PMID 14007781.

- ↑ Blank, Harvey (1961). "Introduction of Dr. René J. Dubos as the First Herman Beerman Lecturer". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 37 (4): 233–234. doi:10.1038/jid.1961.38. PMID 13706567.

- ↑ Wittgenstein, E.; Berry, H. K. (1960). "Staining of Skin with Dihydroxyacetone". Science 132 (3431): 894–5. doi:10.1126/science.132.3431.894. PMID 13845496. Bibcode: 1960Sci...132..894W.

- ↑ "Are 'Spray-On' Tans Safe? Experts Raise Questions as Industry Puts Out Warnings". https://abcnews.go.com/Health/safety-popular-spray-tans-question-protected/story?id=16542918&page=3.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Drysdale, G.S.; Fleet, G.H. (1988). "Acetic acid bacteria in winemaking: a review". American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 39 (2): 143–154. http://ajevonline.org/content/39/2/143.short.

- ↑ Margalith, Pinhas (1981). Flavor microbiology. Thomas. ISBN 978-0-398-04083-3. https://archive.org/details/flavormicrobiolo0000marg.[page needed]

- ↑ Boulton, Roger B.; Singleton, Vernon L.; Bisson, Linda F.; Kunkee, Ralph E. (1999). Principles and Practices of Winemaking. Springer. ISBN 978-0-8342-1270-1.[page needed]

- ↑ Eschenbruch, B.; Dittricha, H. H. (1986). "Stoffbildungen von Essigbakterien in bezug auf ihre Bedeutung für die Weinqualität". Zentralblatt für Mikrobiologie 141 (4): 279–89. doi:10.1016/S0232-4393(86)80045-2.

- ↑ 21 C.F.R. 73.1150

External links

- How Stuff Works

- US FDA/CFSAN - Tanning Pills

- American Academy of Dermatology on Self Tanners

- DHA and Vitiligo

- Fesq, H.; Brockow, K.; Strom, K.; Mempel, M.; Ring, J.; Abeck, D. (2001). "Dihydroxyacetone in a New Formulation – A Powerful Therapeutic Option in Vitiligo". Dermatology 203 (3): 241–3. doi:10.1159/000051757. PMID 11701979.

- Draelos, Zoe D. (2002). "Self-Tanning Lotions: Are They a Healthy Way to Achieve a Tan?". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 3 (5): 317–8. doi:10.2165/00128071-200203050-00003. PMID 12069637.

- New Zealand Dermatological Society recommends sunless tanners

|