Astronomy:Direct collapse black hole

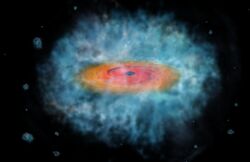

Direct collapse black holes (DCBHs) are high-mass black hole seeds,[2][3][4][5] putatively formed within the redshift range z=15–30,[6] when the Universe was about 100–250 million years old. Unlike seeds formed from the first population of stars (also known as Population III stars), direct collapse black hole seeds are formed by a direct, general relativistic instability. They are very massive, with a typical mass at formation of ~105 M☉.[3][7] This category of black hole seeds was originally proposed theoretically to alleviate the challenge in building supermassive black holes already at redshift z~7, as numerous observations to date have confirmed.[1][8][9][10][11]

Formation

Direct collapse black holes (DCBHs) are massive black hole seeds theorized to have formed in the high-redshift Universe and with typical masses at formation of ~105 M☉, but spanning between 104 M☉ and 106 M☉. The environmental physical conditions to form a DCBH (as opposed to a cluster of stars) are the following:[3][4]

- Metal-free gas (gas containing only hydrogen and helium).

- Atomic-cooling gas.

- Sufficiently large flux of Lyman–Werner photons, in order to destroy hydrogen molecules, which are very efficient gas coolants.[12][13]

The previous conditions are necessary to avoid gas cooling and, hence, fragmentation of the primordial gas cloud. Unable to fragment and form stars, the gas cloud undergoes a gravitational collapse of the entire structure, reaching extremely large values of the matter density at the core, of the order of ~107 g/cm3.[14] At this density, the object undergoes a general relativistic instability,[14] which leads to the formation of a black hole of a typical mass ~105 M☉, and up to 1 million M☉. The occurrence of the general relativistic instability, as well as the absence of the intermediate stellar phase, led to the denomination of direct collapse black hole. In other words, these objects collapse directly from the primordial gas cloud, not from a stellar progenitor as prescribed in standard black hole models.[15]

A computer simulation reported in July 2022 showed that a halo at the rare convergence of strong, cold accretion flows can create massive black holes seeds without the need for ultraviolet backgrounds, supersonic streaming motions or even atomic cooling. Cold flows produced turbulence in the halo, which suppressed star formation. In the simulation, no stars formed in the halo until it had grown to 40 million solar masses at a redshift of 25.7 when the halo's gravity was finally able to overcome the turbulence; the halo then collapsed and formed two supermassive stars that died as DCBHs of 31,000 and 40,000 M☉.[16][17]

Demography

Direct collapse black holes are generally thought to be extremely rare objects in the high-redshift Universe, because the three fundamental conditions for their formation (see above in section Formation) are challenging to be met all together in the same gas cloud.[18][19] Current cosmological simulations suggest that DCBHs could be as rare as only about 1 per cubic gigaparsec at redshift 15.[19] The prediction on their number density is highly dependent on the minimum flux of Lyman–Werner photons required for their formation[20] and can be as large as ~107 DCBHs per cubic gigaparsec in the most optimistic scenarios.[19]

Detection

In 2016, a team led by Harvard University astrophysicist Fabio Pacucci identified the first two candidate direct collapse black holes,[21][22] using data from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory.[23][24][25][26] The two candidates, both at redshift [math]\displaystyle{ z \gt 6 }[/math], were found in the CANDELS GOODS-S field and matched the spectral properties predicted for this type of astrophysical sources.[27] In particular, these sources are predicted to have a significant excess of infrared radiation, when compared to other categories of sources at high redshift.[21] Additional observations, in particular with the James Webb Space Telescope, will be crucial to investigate the properties of these sources and confirm their nature.[28]

Difference from primordial and stellar collapse black holes

A primordial black hole is the result of the direct collapse of energy, ionized matter, or both, during the inflationary or radiation-dominated eras, while a direct collapse black hole is the result of the collapse of unusually dense and large regions of gas.[29] Note that a black hole formed by the collapse of a Population III star is not considered "direct" collapse.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "NASA Telescopes Find Clues For How Giant Black Holes Formed So Quickly". Chandra X-ray Observatory. 24 May 2016. https://chandra.si.edu/press/16_releases/press_052416.html.

- ↑ Loeb, Abraham; Rasio, Frederic A. (1994-09-01). "Collapse of primordial gas clouds and the formation of quasar black holes". The Astrophysical Journal 432: 52–61. doi:10.1086/174548. Bibcode: 1994ApJ...432...52L. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1994ApJ...432...52L.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Bromm, Volker; Loeb, Abraham (2003-10-01). "Formation of the First Supermassive Black Holes". The Astrophysical Journal 596 (1): 34–46. doi:10.1086/377529. Bibcode: 2003ApJ...596...34B. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003ApJ...596...34B.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lodato, Giuseppe; Natarajan, Priyamvada (2006-10-01). "Supermassive black hole formation during the assembly of pre-galactic discs". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 371 (4): 1813–1823. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10801.x. Bibcode: 2006MNRAS.371.1813L. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006MNRAS.371.1813L.

- ↑ Siegel, Ethan. "'Direct Collapse' Black Holes May Explain Our Universe's Mysterious Quasars" (in en). https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2017/12/26/direct-collapse-black-holes-may-explain-our-universes-mysterious-quasars/.

- ↑ Yue, Bin; Ferrara, Andrea; Salvaterra, Ruben; Xu, Yidong; Chen, Xuelei (2014-05-01). "The brief era of direct collapse black hole formation". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 440 (2): 1263–1273. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu351. Bibcode: 2014MNRAS.440.1263Y. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2014MNRAS.440.1263Y.

- ↑ Rees, Martin J.; Volonteri, Marta (2007-04-01). "Massive black holes: formation and evolution". Black Holes from Stars to Galaxies – Across the Range of Masses 238: 51–58. doi:10.1017/S1743921307004681. Bibcode: 2007IAUS..238...51R. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007IAUS..238...51R.

- ↑ Bañados, Eduardo; Venemans, Bram P.; Mazzucchelli, Chiara; Farina, Emanuele P.; Walter, Fabian; Wang, Feige; Decarli, Roberto; Stern, Daniel et al. (2018-01-01). "An 800-million-solar-mass black hole in a significantly neutral Universe at a redshift of 7.5". Nature 553 (7689): 473–476. doi:10.1038/nature25180. PMID 29211709. Bibcode: 2018Natur.553..473B. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2018Natur.553..473B.

- ↑ Fan, Xiaohui; Narayanan, Vijay K.; Lupton, Robert H.; Strauss, Michael A.; Knapp, Gillian R.; Becker, Robert H.; White, Richard L.; Pentericci, Laura et al. (2001-12-01). "A Survey of z>5.8 Quasars in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. I. Discovery of Three New Quasars and the Spatial Density of Luminous Quasars at z~6". The Astronomical Journal 122 (6): 2833–2849. doi:10.1086/324111. Bibcode: 2001AJ....122.2833F. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2001AJ....122.2833F.

- ↑ Yang, Jinyi; Wang, Feige; Fan, Xiaohui; Hennawi, Joseph F.; Davies, Frederick B.; Yue, Minghao; Banados, Eduardo; Wu, Xue-Bing et al. (2020-07-01). "Poniua'ena: A Luminous z = 7.5 Quasar Hosting a 1.5 Billion Solar Mass Black Hole". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 897 (1): L14. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab9c26. Bibcode: 2020ApJ...897L..14Y.

- ↑ "Monster Black Hole Found in the Early Universe" (in en). 2020-06-24. https://www.gemini.edu/pr/monster-black-hole-found-early-universe.

- ↑ Regan, John A.; Johansson, Peter H.; Wise, John H. (2014-11-01). "The Direct Collapse of a Massive Black Hole Seed under the Influence of an Anisotropic Lyman–Werner Source". The Astrophysical Journal 795 (2): 137. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/795/2/137. Bibcode: 2014ApJ...795..137R. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2014ApJ...795..137R.

- ↑ Sugimura, Kazuyuki; Omukai, Kazuyuki; Inoue, Akio K. (2014-11-01). "The critical radiation intensity for direct collapse black hole formation: dependence on the radiation spectral shape". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 445 (1): 544–553. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1778. Bibcode: 2014MNRAS.445..544S. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2014MNRAS.445..544S.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Montero, Pedro J.; Janka, Hans-Thomas; Müller, Ewald (2012-04-01). "Relativistic Collapse and Explosion of Rotating Supermassive Stars with Thermonuclear Effects". The Astrophysical Journal 749 (1): 37. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/749/1/37. Bibcode: 2012ApJ...749...37M. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2012ApJ...749...37M.

- ↑ Natarajan, Priyamvada (2018). "The Puzzle of the First Black Holes". Scientific American 318 (2): 24–29. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0218-24. PMID 29337944. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-puzzle-of-the-first-black-holes/.

- ↑ "Revealing the origin of the first supermassive black holes". Nature. 6 July 2022. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-01560-y. PMID 35794378. "State-of-the-art computer simulations show that the first supermassive black holes were born in rare, turbulent reservoirs of gas in the primordial Universe without the need for finely tuned, exotic environments — contrary to what has been thought for almost two decades.".

- ↑ "Scientists discover how first quasars in universe formed". Provided by University of Portsmouth. 6 July 2022. https://phys.org/news/2022-07-scientists-quasars-universe.html.

- ↑ Agarwal, Bhaskar; Dalla Vecchia, Claudio; Johnson, Jarrett L.; Khochfar, Sadegh; Paardekooper, Jan-Pieter (2014-09-01). "The First Billion Years project: birthplaces of direct collapse black holes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 443 (1): 648–657. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1112. Bibcode: 2014MNRAS.443..648A. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2014MNRAS.443..648A.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Habouzit, Mélanie; Volonteri, Marta; Latif, Muhammad; Dubois, Yohan; Peirani, Sébastien (2016-11-01). "On the number density of 'direct collapse' black hole seeds". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 463 (1): 529–540. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1924. Bibcode: 2016MNRAS.463..529H. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2016MNRAS.463..529H.

- ↑ Latif, M. A.; Bovino, S.; Grassi, T.; Schleicher, D. R. G.; Spaans, M. (2015-01-01). "How realistic UV spectra and X-rays suppress the abundance of direct collapse black holes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 446 (3): 3163–3177. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2244. Bibcode: 2015MNRAS.446.3163L. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2015MNRAS.446.3163L.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Pacucci, Fabio; Ferrara, Andrea; Grazian, Andrea; Fiore, Fabrizio; Giallongo, Emanuele; Puccetti, Simonetta (2016-06-01). "First identification of direct collapse black hole candidates in the early Universe in CANDELS/GOODS-S". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 459 (2): 1432–1439. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw725. Bibcode: 2016MNRAS.459.1432P. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2016MNRAS.459.1432P.

- ↑ "The first Direct Collapse Black Hole candidates" (in en-US). https://www.fabiopacucci.com/impact/press-coverage/the-first-direct-collapse-black-hole-candidates/.

- ↑ Northon, Karen (2016-05-24). "NASA Telescopes Find Clues For How Giant Black Holes Formed So Quickly". http://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-telescopes-find-clues-for-how-giant-black-holes-formed-so-quickly.

- ↑ "Mystery of supermassive black holes might be solved" (in en-US). 25 May 2016. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/mystery-of-supermassive-black-holes-might-be-solved/.

- ↑ "Mystery of Massive Black Holes May Be Answered by NASA Telescopes" (in en). https://abcnews.go.com/Technology/mystery-massive-black-holes-answered-nasa-telescopes/story?id=39364430.

- ↑ Reynolds, Emily (2016-05-25). "Hubble discovers clues to how supermassive black holes form" (in en-GB). Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/hubble-space-telescope-black-holes.

- ↑ Pacucci, Fabio; Ferrara, Andrea; Volonteri, Marta; Dubus, Guillaume (2015-12-01). "Shining in the dark: the spectral evolution of the first black holes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 454 (4): 3771–3777. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2196. Bibcode: 2015MNRAS.454.3771P. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2015MNRAS.454.3771P.

- ↑ Natarajan, Priyamvada; Pacucci, Fabio; Ferrara, Andrea; Agarwal, Bhaskar; Ricarte, Angelo; Zackrisson, Erik; Cappelluti, Nico (2017-04-01). "Unveiling the First Black Holes With JWST:Multi-wavelength Spectral Predictions". The Astrophysical Journal 838 (2): 117. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa6330. Bibcode: 2017ApJ...838..117N.

- ↑ Carr, Bernard; Kühnel, Florian (19 October 2020). "Primordial Black Holes as Dark Matter: Recent Developments" (in en). Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 70 (1): 355–394. doi:10.1146/annurev-nucl-050520-125911. ISSN 0163-8998. Bibcode: 2020ARNPS..70..355C. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-nucl-050520-125911. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

Further reading

- Pandey, Kanhaiya L.; Mangalam, A. (2018). "Role of primordial black holes in the direct collapse scenario of supermassive black hole formation at high redshifts". Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy 39 (1): 9. doi:10.1007/s12036-018-9513-x. Bibcode: 2018JApA...39....9P.

- Mayer, Lucio; Bonoli, Silvia (2019). "The route to massive black hole formation via merger-driven direct collapse: A review". Reports on Progress in Physics 82 (1): 016901. doi:10.1088/1361-6633/aad6a5. PMID 30057369. Bibcode: 2019RPPh...82a6901M.

- Haemmerlé, Lionel; Heger, Alexander; Woods, Tyrone E. (2020). "On monolithic supermassive stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 494 (2): 2236–2243. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa763.

|