Biology:Loricifera

| Loricifera | |

|---|---|

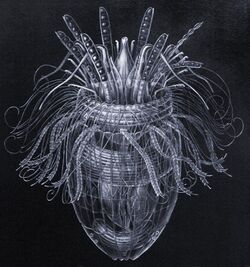

| |

| Pliciloricus enigmaticus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa |

| Phylum: | Loricifera Kristensen, 1983[2] |

| Families | |

| |

Loricifera (from Latin, lorica, corselet (armour) + ferre, to bear) is a phylum of very small to microscopic marine cycloneuralian sediment-dwelling animals with 43 described species.[3] and approximately 100 more that have been collected and not yet described.[4] Their sizes range from 100 μm to ca. 1 mm.[5]

They are characterised by a protective outer case called a lorica and their habitat is in the spaces between marine gravel to which they attach themselves. The phylum was discovered in 1983 by R.M. Kristensen, near Roscoff, France .[6] They are among the most recently discovered groups of animals.[7] They attach themselves quite firmly to the substrate, and hence remained undiscovered for so long.[8] The first specimen was collected in the 1970s, and described in 1983.[7] They are found at all depths, in different sediment types, and in all latitudes.[8]

Morphology

The animals have a head, mouth, and digestive system, as well as the lorica. The head (which contains the mouth and the brain), a trunk region surrounded by six plates that make up the 'lorica' or corselet and – in between these two – the neck region. Loricifera have a well developed brain and each scalid is individually connected to the brain by nerves. The armor-like lorica consists of a protective external shell or case of encircling plicae.[9] There is no circulatory system and no endocrine system. Many of the larvae are acoelomate, with some adults being pseudocoelomate, and some remaining acoelomate.[7] Development is generally direct, though there are so-called Higgins larvae, which differ from adults in several respects. As adults, the animals are gonochoric. Very complex and plastic life cycles of pliciloricids include also paedogenetic stages with different forms of parthenogenetic reproduction.[4] Fossils have been dated to the late Cambrian.[10]

Taxonomic affinity

Morphological studies have traditionally placed the phylum in the vinctiplicata with the Priapulida; this plus the Kinorhyncha constitutes the taxon Scalidophora. The three phyla share four characters in common – chitinous cuticle, rings of scalids on the introvert, flosculi, and two rings of introvert retracts.[6][7] However, despite a 2015 study showing the phylum's closest relatives being the Panarthropoda,[11] a 2022 study again showed that it belonged to the Scalidophora and told that further, more comprehensive genetic tests will be required to find its actual position in Ecdysozoa.[12]

Evolutionary history

The loriciferans are believed to be miniaturized descendants of a larger organism, perhaps resembling the Cambrian fossil Sirilorica.[13] However, the fossil record of the microscopic non-mineralized group is (perhaps unsurprisingly) scarce, so it is difficult to trace out the evolutionary history of the phylum in any detail.

The 2017 discovery of Cambrian Period Eolorica deadwoodensis may shed some light on the group's history.[14]

In anoxic environments

Three species of Loricifera have been found in the oxygen-free sediments at the bottom of the L'Atalante basin in Mediterranean Sea, more than 3,000 meters down, the first multicellular organisms known to spend their entire lives in an anoxic environment. Initially, it was thought that they are able to do this because their mitochondria act like hydrogenosomes, allowing them to respire anaerobically.[15][16] However, by 2021, questions arose as to whether or not they have mitochondria.[17]

The newly reported animals complete their life cycle in the total absence of light and oxygen, and they are less than a millimetre in size.[18] They were collected from a deep basin at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, where they inhabit a nearly salt-saturated brine that, because of its density (> 1.2 g/cm³), does not mix with the waters above.[18] As a consequence, this environment is completely anoxic and, due to the activity of sulfate reducers, contains sulphide at a concentration of 2.9 mM.[18] Despite such harsh conditions, this anoxic and sulphidic environment is teeming with microbial life, both chemosynthetic prokaryotes that are primary producers, and a broad diversity of eukaryotic heterotrophs at the next trophic level.[18]

Taxa

- Nanaloricidae Kristensen, 1983

- Phoeniciloricus Nanaloricus

- Kristensen, 1983 Kristensen & Gad, 2004

- Gad, 2004 Spinoloricus

- Australoricus Heiner, 2007

- Armorloricus Heiner, Boesgaard & Kristensen, 2009

- Pliciloricidae Higgins & Kristensen, 1986

- Gad, 2005 Higgins & Kristensen 1986

- [[Fujimoto, Yamasaki, Kimura et al., 2020[19]]] Rugiloricus

- Pliciloricus Higgins & Kristensen, 1986

- Titaniloricus Wataloricus

- Urnaloricidae Heiner & Møbjerg Kristensen, 2009

- Urnaloricus Heiner & Møbjerg Kristensen, 2009

- Extinct taxa (unclassified)

- Peel, 2010 Harvey & Butterfield, 2017

- †Orstenoloricus †Eolorica

- Maas et al. 2009 †Sirilorica?

References

- ↑ Peel, John S.; Stein, Martin; Kristensen, Reinhardt Møbjerg (9 August 2013). "Life Cycle and Morphology of a Cambrian Stem-Lineage Loriciferan". PLoS ONE 8 (8): e73583. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073583. PMID 23991198. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...873583P.

- ↑ "Loricifera, a new phylum with Aschelminthes characters from the meiobenthos". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 21 (3): 163–180. 2009-04-27. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1983.tb00285.x. ISSN 0947-5745.

- ↑ Cardoso Neves, Ricardo; Kristensen, Reinhardt Møbjerg; Møbjerg, Nadja (5 May 2021). "New records on the rich loriciferan fauna of Trezen ar Skoden (Roscoff, France): Description of two new species of Nanaloricus and the new genus Scutiloricus". PLOS ONE 16 (5): e0250403. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250403. id 10.1371. PMID 33951070. Bibcode: 2021PLoSO..1650403N.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gad, Gunnar (17 June 2005). "Successive reduction of the last instar larva of Loricifera, as evidenced by two new species of Pliciloricus from the Great Meteor Seamount (Atlantic Ocean)". Zoologischer Anzeiger 243 (4): 239–271. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2004.09.001.

- ↑ Heiner, Iben (2005). "Preliminary account of the Loriciferan fauna of the Faroe Bank (NE Atlantic)". Annales Societatis Scientiatum Færoensis Supplementum 41: 213–219. http://www.forskningsdatabasen.dk/en/catalog/2185942497. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Heiner, Iben (18 March 2005). "Two new species of the genus Pliciloricus (Loricifera, Pliciloricidae) from the Faroe Bank, North Atlantic". Zoologischer Anzeiger 243 (3): 121–138. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2004.05.002.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "An introduction to Loricifera, Cycliophora, and Micrognathozoa". Integrative and Comparative Biology 42 (3): 641–651. July 2002. doi:10.1093/icb/42.3.641. PMID 21708760.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard S.; Barnes, Robert D., eds (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). p. 776. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780030259821/page/776.

- ↑ Heiner, Iben; Sorensen, Martin Vinther; Kristensen, Reinhardt Mobjerg (2004). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. 1. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. pp. 343–350.

- ↑ "Discovery of new fossil from half billion years ago sheds light on life on Earth: Scientists find 'unfossilizable' creature". Science Daily (Press release). January 2017.

- ↑ Yamasaki, Hiroshi; Fujimoto, Shinta; Miyazaki, Katsumi (2015-06-30). "Phylogenetic position of Loricifera inferred from nearly complete 18S and 28S rRNA gene sequences". Zoological Letters 1: 18. doi:10.1186/s40851-015-0017-0. ISSN 2056-306X. PMID 26605063.

- ↑ Howard, R. J., Giacomelli, M., Lozano-Fernandez, J., Edgecombe, G. D., Fleming, J. F., Kristensen, R. M., Ma, X., Olesen, J., Sørensen, M. V., Thomsen, P. F., Wills, M. A., Donoghue, P. C., & Pisani, D. (2022). The Ediacaran origin of ecdysozoa: Integrating fossil and Phylogenomic Data. Journal of the Geological Society, 179 (4). https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2021-107

- ↑ Peel, John S. (March 2010). "A corset-like fossil from the Cambrian Sirius Passet lagerstätte of North Greenland and its implications for cycloneuralian evolution". Journal of Paleontology 84 (2): 332–340. doi:10.1666/09-102R.1. Bibcode: 2010JPal...84..332P.

- ↑ Harvey, Thomas H.P.; Butterfield, Nicholas J. (30 January 2017). "Exceptionally preserved Cambrian loriciferans and the early animal invasion of the meiobenthos". Nature Ecology and Evolution 1 (3): 0022. doi:10.1038/s41559-016-0022. PMID 28812727. http://eprints.esc.cam.ac.uk/3810/2/s41559-016-0022-s1.pdf.

- ↑ Fang, Janet (8 April 2010). "Animals thrive without oxygen at sea bottom". Nature 464 (7290): 825. doi:10.1038/464825b. PMID 20376121. Bibcode: 2010Natur.464..825F.

- ↑ Milius, Susan (9 April 2010). "Briny deep basin may be home to animals thriving without oxygen". https://www.sciencenews.org/article/briny-deep-basin-may-be-home-animals-thriving-without-oxygen.

- ↑ Snyder, Alison (6 May 2021). "Something wondrous". https://www.axios.com/newsletters/axios-science-94589196-83ae-496f-b201-4948648402e0.html.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Mentel, Marek; Martin, William (6 April 2010). "Anaerobic animals from an ancient, anoxic ecological niche". BMC Biology 8: 32. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-32. PMID 20370917.

- ↑ Fujimoto, Shinta; Yamasaki, Hiroshi; Kimura, Taeko; Ohtsuka, Susumu; Kristensen, Reinhardt Møbjerg (14 November 2020). "A new genus and species of Loricifera (Nanaloricida: Pliciloricidae) from the deep waters of Japan". Marine Biodiversity 50 (6): 103. doi:10.1007/s12526-020-01130-3.

Further reading

- Bernhard, Joan M.; Morrison, Colin R.; Pape, Ellen; Beaudoin, David J.; Todaro, M. Antonio; Pachiadaki, Maria G.; Kormas, Konstantinos Ar.; Edgcomb, Virginia P. (2015). "Metazoans of redoxcline sediments in Mediterranean deep-sea hypersaline anoxic basins". BMC Biology 13: 105. doi:10.1186/s12915-015-0213-6. PMID 26652623.

- Danovaro, Roberto; Dell'Anno, Antonio; Pusceddu, Antonio; Gambi, Cristina; Heiner, Iben; Kristensen, Reinhardt Mobjerg (2010). "The first metazoa living in permanently anoxic conditions". BMC Biology 8: 30. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-30. PMID 20370908.

- Fox-Skelly, Jasmin (25 January 2017). "There is one animal that seems to survive without oxygen". BBC. http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20170125-there-is-one-animal-that-seems-to-survive-without-oxygen.

- Heiner, Iben (2008). "Rugiloricus bacatus sp. nov. (Loricifera ‐Pliciloricidae) and a ghost‐larva with paedogenetic reproduction". Systematics and Biodiversity 6 (2): 225–47. doi:10.1017/S147720000800265X.

- Ramel, Gordon (2 March 2020). "The Brush Heads (Phylum Loricifera)". http://www.earthlife.net/inverts/loricifera.html.[self-published source?]

- "Can animals thrive without oxygen?" (Press release). Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. 28 January 2016.

- "Discovery of new fossil from half billion years ago sheds light on life on Earth". https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/01/170130133409.htm.

Wikidata ☰ {{{from}}} entry

|