NP (complexity)

| Unsolved problem in computer science: [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{P\ \overset{?}{=}\ NP} }[/math] (more unsolved problems in computer science)

|

In computational complexity theory, NP (nondeterministic polynomial time) is a complexity class used to classify decision problems. NP is the set of decision problems for which the problem instances, where the answer is "yes", have proofs verifiable in polynomial time by a deterministic Turing machine, or alternatively the set of problems that can be solved in polynomial time by a nondeterministic Turing machine.[2][Note 1]

- NP is the set of decision problems solvable in polynomial time by a nondeterministic Turing machine.

- NP is the set of decision problems verifiable in polynomial time by a deterministic Turing machine.

The first definition is the basis for the abbreviation NP; "nondeterministic, polynomial time". These two definitions are equivalent because the algorithm based on the Turing machine consists of two phases, the first of which consists of a guess about the solution, which is generated in a nondeterministic way, while the second phase consists of a deterministic algorithm that verifies whether the guess is a solution to the problem.[3]

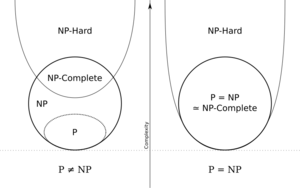

It is easy to see that the complexity class P (all problems solvable, deterministically, in polynomial time) is contained in NP (problems where solutions can be verified in polynomial time), because if a problem is solvable in polynomial time, then a solution is also verifiable in polynomial time by simply solving the problem. But NP contains many more problems,[Note 2] the hardest of which are called NP-complete problems. An algorithm solving such a problem in polynomial time is also able to solve any other NP problem in polynomial time. The most important P versus NP (“P = NP?”) problem, asks whether polynomial-time algorithms exist for solving NP-complete, and by corollary, all NP problems. It is widely believed that this is not the case.[4]

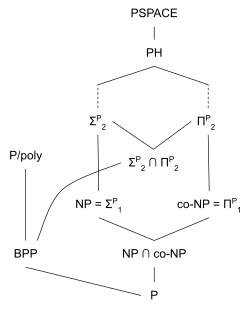

The complexity class NP is related to the complexity class co-NP, for which the answer "no" can be verified in polynomial time. Whether or not NP = co-NP is another outstanding question in complexity theory.[5]

Formal definition

The complexity class NP can be defined in terms of NTIME as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{NP} = \bigcup_{k\in\mathbb{N}} \mathsf{NTIME}(n^k), }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{NTIME}(n^k) }[/math] is the set of decision problems that can be solved by a nondeterministic Turing machine in [math]\displaystyle{ O(n^k) }[/math] time.

Alternatively, NP can be defined using deterministic Turing machines as verifiers. A language L is in NP if and only if there exist polynomials p and q, and a deterministic Turing machine M, such that

- For all x and y, the machine M runs in time p(|x|) on input [math]\displaystyle{ (x,y) }[/math].

- For all x in L, there exists a string y of length q(|x|) such that [math]\displaystyle{ M(x, y) = 1 }[/math].

- For all x not in L and all strings y of length q(|x|), [math]\displaystyle{ M(x, y) = 0 }[/math].

Background

Many computer science problems are contained in NP, like decision versions of many search and optimization problems.

Verifier-based definition

In order to explain the verifier-based definition of NP, consider the subset sum problem: Assume that we are given some integers, {−7, −3, −2, 5, 8}, and we wish to know whether some of these integers sum up to zero. Here the answer is "yes", since the integers {−3, −2, 5} corresponds to the sum (−3) + (−2) + 5 = 0.

To answer whether some of the integers add to zero we can create an algorithm that obtains all the possible subsets. As the number of integers that we feed into the algorithm becomes larger, both the number of subsets and the computation time grows exponentially.

But notice that if we are given a particular subset, we can efficiently verify whether the subset sum is zero, by summing the integers of the subset. If the sum is zero, that subset is a proof or witness for the answer is "yes". An algorithm that verifies whether a given subset has sum zero is a verifier. Clearly, summing the integers of a subset can be done in polynomial time, and the subset sum problem is therefore in NP.

The above example can be generalized for any decision problem. Given any instance I of problem [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi }[/math] and witness W, if there exists a verifier V so that given the ordered pair (I, W) as input, V returns "yes" in polynomial time if the witness proves that the answer is "yes" or "no" in polynomial time otherwise, then [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi }[/math] is in NP.

The "no"-answer version of this problem is stated as: "given a finite set of integers, does every non-empty subset have a nonzero sum?". The verifier-based definition of NP does not require an efficient verifier for the "no"-answers. The class of problems with such verifiers for the "no"-answers is called co-NP. In fact, it is an open question whether all problems in NP also have verifiers for the "no"-answers and thus are in co-NP.

In some literature the verifier is called the "certifier", and the witness the "certificate".[2]

Machine-definition

Equivalent to the verifier-based definition is the following characterization: NP is the class of decision problems solvable by a nondeterministic Turing machine that runs in polynomial time. That is to say, a decision problem [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi }[/math] is in NP whenever [math]\displaystyle{ \Pi }[/math] is recognized by some polynomial-time nondeterministic Turing machine [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] with an existential acceptance condition, meaning that [math]\displaystyle{ w \in \Pi }[/math] if and only if some computation path of [math]\displaystyle{ M(w) }[/math] leads to an accepting state. This definition is equivalent to the verifier-based definition because a nondeterministic Turing machine could solve an NP problem in polynomial time by nondeterministically selecting a certificate and running the verifier on the certificate. Similarly, if such a machine exists, then a polynomial time verifier can naturally be constructed from it.

In this light, we can define co-NP dually as the class of decision problems recognizable by polynomial-time nondeterministic Turing machines with an existential rejection condition. Since an existential rejection condition is exactly the same thing as a universal acceptance condition, we can understand the NP vs. co-NP question as asking whether the existential and universal acceptance conditions have the same expressive power for the class of polynomial-time nondeterministic Turing machines.

Properties

NP is closed under union, intersection, concatenation, Kleene star and reversal. It is not known whether NP is closed under complement (this question is the so-called "NP versus co-NP" question).

Why some NP problems are hard to solve

Because of the many important problems in this class, there have been extensive efforts to find polynomial-time algorithms for problems in NP. However, there remain a large number of problems in NP that defy such attempts, seeming to require super-polynomial time. Whether these problems are not decidable in polynomial time is one of the greatest open questions in computer science (see P versus NP ("P = NP") problem for an in-depth discussion).

An important notion in this context is the set of NP-complete decision problems, which is a subset of NP and might be informally described as the "hardest" problems in NP. If there is a polynomial-time algorithm for even one of them, then there is a polynomial-time algorithm for all the problems in NP. Because of this, and because dedicated research has failed to find a polynomial algorithm for any NP-complete problem, once a problem has been proven to be NP-complete, this is widely regarded as a sign that a polynomial algorithm for this problem is unlikely to exist.

However, in practical uses, instead of spending computational resources looking for an optimal solution, a good enough (but potentially suboptimal) solution may often be found in polynomial time. Also, the real-life applications of some problems are easier than their theoretical equivalents.

Equivalence of definitions

The two definitions of NP as the class of problems solvable by a nondeterministic Turing machine (TM) in polynomial time and the class of problems verifiable by a deterministic Turing machine in polynomial time are equivalent. The proof is described by many textbooks, for example, Sipser's Introduction to the Theory of Computation, section 7.3.

To show this, first, suppose we have a deterministic verifier. A non-deterministic machine can simply nondeterministically run the verifier on all possible proof strings (this requires only polynomially many steps because it can nondeterministically choose the next character in the proof string in each step, and the length of the proof string must be polynomially bounded). If any proof is valid, some path will accept; if no proof is valid, the string is not in the language and it will reject.

Conversely, suppose we have a non-deterministic TM called A accepting a given language L. At each of its polynomially many steps, the machine's computation tree branches in at most a finite number of directions. There must be at least one accepting path, and the string describing this path is the proof supplied to the verifier. The verifier can then deterministically simulate A, following only the accepting path, and verifying that it accepts at the end. If A rejects the input, there is no accepting path, and the verifier will always reject.

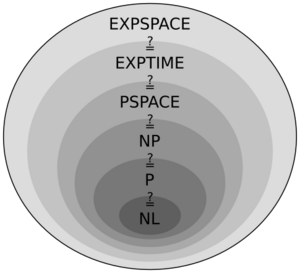

Relationship to other classes

NP contains all problems in P, since one can verify any instance of the problem by simply ignoring the proof and solving it. NP is contained in PSPACE—to show this, it suffices to construct a PSPACE machine that loops over all proof strings and feeds each one to a polynomial-time verifier. Since a polynomial-time machine can only read polynomially many bits, it cannot use more than polynomial space, nor can it read a proof string occupying more than polynomial space (so we do not have to consider proofs longer than this). NP is also contained in EXPTIME, since the same algorithm operates in exponential time.

co-NP contains those problems that have a simple proof for no instances, sometimes called counterexamples. For example, primality testing trivially lies in co-NP, since one can refute the primality of an integer by merely supplying a nontrivial factor. NP and co-NP together form the first level in the polynomial hierarchy, higher only than P.

NP is defined using only deterministic machines. If we permit the verifier to be probabilistic (this, however, is not necessarily a BPP machine[6]), we get the class MA solvable using an Arthur–Merlin protocol with no communication from Arthur to Merlin.

The relationship between BPP and NP is unknown: it is not known whether BPP is a subset of NP, NP is a subset of BPP or neither. If NP is contained in BPP, which is considered unlikely since it would imply practical solutions for NP-complete problems, then NP = RP and PH ⊆ BPP.[7]

NP is a class of decision problems; the analogous class of function problems is FNP.

The only known strict inclusions come from the time hierarchy theorem and the space hierarchy theorem, and respectively they are [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{NP \subsetneq NEXPTIME} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{NP \subsetneq EXPSPACE} }[/math].

Other characterizations

In terms of descriptive complexity theory, NP corresponds precisely to the set of languages definable by existential second-order logic (Fagin's theorem).

NP can be seen as a very simple type of interactive proof system, where the prover comes up with the proof certificate and the verifier is a deterministic polynomial-time machine that checks it. It is complete because the right proof string will make it accept if there is one, and it is sound because the verifier cannot accept if there is no acceptable proof string.

A major result of complexity theory is that NP can be characterized as the problems solvable by probabilistically checkable proofs where the verifier uses O(log n) random bits and examines only a constant number of bits of the proof string (the class PCP(log n, 1)). More informally, this means that the NP verifier described above can be replaced with one that just "spot-checks" a few places in the proof string, and using a limited number of coin flips can determine the correct answer with high probability. This allows several results about the hardness of approximation algorithms to be proven.

Examples

P

All problems in P, denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{P \subseteq NP} }[/math]. Given a certificate for a problem in P, we can ignore the certificate and just solve the problem in polynomial time.

Integer factorization

The decision problem version of the integer factorization problem: given integers n and k, is there a factor f with 1 < f < k and f dividing n?[8]

NP-complete problems

Every NP-complete problem is in NP.

Boolean satisfiability

The Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT), where we want to know whether or not a certain formula in propositional logic with Boolean variables is true for some value of the variables.[9]

Travelling salesman

The decision version of the travelling salesman problem is in NP. Given an input matrix of distances between n cities, the problem is to determine if there is a route visiting all cities with total distance less than k.

A proof can simply be a list of the cities. Then verification can clearly be done in polynomial time. It simply adds the matrix entries corresponding to the paths between the cities.

A nondeterministic Turing machine can find such a route as follows:

- At each city it visits it will "guess" the next city to visit, until it has visited every vertex. If it gets stuck, it stops immediately.

- At the end it verifies that the route it has taken has cost less than k in O(n) time.

One can think of each guess as "forking" a new copy of the Turing machine to follow each of the possible paths forward, and if at least one machine finds a route of distance less than k, that machine accepts the input. (Equivalently, this can be thought of as a single Turing machine that always guesses correctly)

A binary search on the range of possible distances can convert the decision version of Traveling Salesman to the optimization version, by calling the decision version repeatedly (a polynomial number of times).[10][8]

Subgraph isomorphism

The subgraph isomorphism problem of determining whether graph G contains a subgraph that is isomorphic to graph H.[11]

See also

- Turing machine – Computation model defining an abstract machine

Notes

References

- ↑ Ladner, R. E. (1975). "On the structure of polynomial time reducibility". J. ACM 22: 151–171. doi:10.1145/321864.321877. Corollary 1.1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kleinberg, Jon; Tardos, Éva (2006). Algorithm Design (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 464. ISBN 0-321-37291-3. https://archive.org/details/algorithmdesign0000klei.

- ↑ Alsuwaiyel, M. H.: Algorithms: Design Techniques and Analysis, p. 283.

- ↑ William Gasarch (June 2002). "The P=?NP poll". SIGACT News 33 (2): 34–47. doi:10.1145/1052796.1052804. https://www.cs.umd.edu/~gasarch/papers/poll.pdf. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ↑ Kleinberg, Jon; Tardos, Éva (2006). Algorithm Design (2nd ed.). p. 496. ISBN 0-321-37291-3. https://archive.org/details/algorithmdesign0000klei.

- ↑ "Complexity Zoo:E". https://complexityzoo.uwaterloo.ca/Complexity_Zoo:E#existsbpp.

- ↑ Lance Fortnow, Pulling Out The Quantumness, December 20, 2005

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Wigderson, Avi. "P, NP and mathematics – a computational complexity perspective". https://www.math.ias.edu/~avi/PUBLICATIONS/MYPAPERS/W06/w06.pdf.

- ↑ Karp, Richard (1972). "Reducibility among Combinatorial Problems". Complexity of Computer Computations. pp. 85–103. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-2001-2_9. ISBN 978-1-4684-2003-6. http://cgi.di.uoa.gr/~sgk/teaching/grad/handouts/karp.pdf.

- ↑ Aaronson, Scott. "P=? NP". https://www.scottaaronson.com/papers/pnp.pdf.

- ↑ Garey, Michael R.; Johnson, David S. (1979). Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-1045-5.

Further reading

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Section 34.2: Polynomial-time verification, pp. 979–983.

- Michael Sipser (1997). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS Publishing. ISBN 0-534-94728-X. https://archive.org/details/introductiontoth00sips. Sections 7.3–7.5 (The Class NP, NP-completeness, Additional NP-complete Problems), pp. 241–271.

- David Harel, Yishai Feldman. Algorithmics: The Spirit of Computing, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 3rd edition, 2004.

External links

- Complexity Zoo: NP

- American Scientist primer on traditional and recent complexity theory research: "Accidental Algorithms"

|