Biology:Human polyomavirus 2

| Human polyomavirus 2 | |

|---|---|

| |

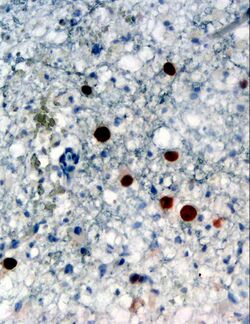

| Immunohistochemical detection of Human polyomavirus 2 protein (stained brown) in a brain biopsy (glia demonstrating progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)) | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Monodnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Shotokuvirae |

| Phylum: | Cossaviricota |

| Class: | Papovaviricetes |

| Order: | Sepolyvirales |

| Family: | Polyomaviridae |

| Genus: | Betapolyomavirus |

| Species: | Human polyomavirus 2

|

| Synonyms | |

Human polyomavirus 2, commonly referred to as the JC virus or John Cunningham virus, is a type of human polyomavirus (formerly known as papovavirus).[3] It was identified by electron microscopy in 1965 by ZuRhein and Chou,[4] and by Silverman and Rubinstein, and later isolated in culture and named using the two initials of a patient, John Cunningham, with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).[5] The virus causes PML and other diseases only in cases of immunodeficiency, as in AIDS or during treatment with immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. in organ transplant patients).[6]

Infection and pathogenesis

The initial site of infection may be the tonsils,[7] or possibly the gastrointestinal tract.[8] The virus then remains latent in the gastrointestinal tract[9] and can also infect the tubular epithelial cells in the kidneys,[10] where it continues to reproduce, shedding virus particles in the urine. In addition, recent studies suggest that this virus may latently infect the human semen[11] as well as the chorionic villi tissues.[12] Serum antibodies against Human polyomavirus 2 have also been found in spontaneous abortion-affected women as well as in women who underwent voluntary interruption of pregnancy.[13]

Human polyomavirus 2 can cross the blood–brain barrier into the central nervous system, where it infects oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, possibly through the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor.[14] Human polyomavirus 2 DNA can be detected in both non-PML affected and PML-affected (see below) brain tissue.[15]

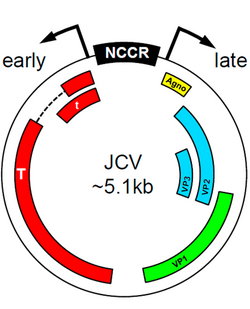

Human polyomavirus 2 found in the central nervous system of PML patients almost invariably have differences in promoter sequence to Human polyomavirus 2 found in healthy individuals. It is thought that these differences in promoter sequence contribute to the fitness of the virus in the CNS and thus to the development of PML.[6] Certain transcription factors present in the early promoter sequences of Human polyomavirus 2 can induce tropism and viral proliferation that leads to PML. The Spi-B factor was shown to be crucial in initiating viral replication in certain strains of transgenic mice.[16] The protein encoded by these early sequences, T-antigen, also plays a key role in viral proliferation,[17] directing the initiation of DNA replication for the virus as well as performing a transcriptional switch to allow for the formation of the various capsid and regulatory proteins needed for viral fitness. Further research is needed to determine the exact etiological role of T-antigen, but there seems to be a connection to the early initiation of the active virus from its archetypal dormant state.[citation needed]

Immunodeficiency or immunosuppression allows Human polyomavirus 2 to reactivate. In the brain, it causes the often fatal progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, or PML, by destroying oligodendrocytes. Whether this represents the reactivation of Human polyomavirus 2 within the CNS or seeding of newly reactivated Human polyomavirus 2 via blood or lymphatics is unknown.[18] Several studies since 2000 have suggested that the virus is also linked to colorectal cancer, as Human polyomavirus 2 has been found in malignant colon tumors, but these findings are still controversial.[19]

Other strains and novel pathological syndromes

Although Human polyomavirus 2 infection is classically associated with white matter demyelination and PML pathogenesis, recent literature has identified viral variants as etiological agents of other novel syndromes. For example, Human polyomavirus 2 has been found to infect the granule cell layer of the cerebellum, while sparing purkinje fibers, ultimately causing severe cerebellar atrophy.[20] This syndrome, called JCV granule cell layer neuronopathy (JCV GCN), is characterized by a productive and lytic infection by a JC variant with a mutation in the VP1 coding region.[citation needed]

Human polyomavirus 2 also appears to mediate encephalopathy, due to infection of cortical pyramidal neurons (CPN) and astrocytes.[20] Analysis of the JCV CPN variant revealed differences from JCV GCN: no mutations were found in the VP1 coding region; however, a 143–base-pair deletion was identified in the agnogene, coding for a 10–amino-acid truncated peptide, which is believed to mediate CPN tropism. Additionally, analysis of the subcellular localization of JC CPN virions in nuclei, cytoplasm, and axons suggests that the virus may travel through axons to increase infectivity.[20]

Human polyomavirus 2 may also be a causative agent of aseptic meningitis (JCVM), as Human polyomavirus 2 was the only pathogen identified in the CSF of certain patients with meningitis. Analysis of the JCVM variant revealed archetype-like regulatory regions with no mutations in coding sequences. The precise molecular mechanisms mediating Human polyomavirus 2 meningeal tropism remain to be found.[20]

Epidemiology

The virus is very common in the general population, infecting 70% to 90% of humans; most people acquire Human polyomavirus 2 in childhood or adolescence.[22][23][24] It is found in high concentrations in urban sewage worldwide, leading some researchers to suspect contaminated water as a typical route of infection.[8]

Minor genetic variations are found consistently in different geographic areas; thus, genetic analysis of Human polyomavirus 2 samples has been useful in tracing the history of human migration.[25] 14 subtypes or genotypes are recognised each associated with a specific geographical region. Three are found in Europe (a, b and c). A minor African type—Af1—occurs in Central and West Africa. The major African type—Af2—is found throughout Africa and also in West and South Asia. Several Asian types are recognised B1-a, B1-b, B1-d, B2, CY, MY and SC.[citation needed]

An alternative numbering scheme numbers the genotypes 1–8 with additional lettering. Types 1 and 4 are found in Europe[26] and in indigenous populations in northern Japan, North-East Siberia and northern Canada. These two types are closely related. Types 3 and 6 are found in sub-Saharan Africa: type 3 was isolated in Ethiopia, Tanzania and South Africa. Type 6 is found in Ghana. Both types are also found in the Biaka Pygmies and Bantus from Central Africa. Type 2 has several variants: subtype 2A is found mainly in the Japanese population and Native Americans (excluding Inuit); 2B is found in Eurasians; 2D is found in Indians and 2E is found in Australians and western Pacific populations. Subtype 7A is found in southern China and South-East Asia. Subtype 7B is found in northern China, Mongolia and Japan Subtype 7C is found in northern and southern China. Subtype 8 is found in Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands. The geographic distribution of JC polyomavirus types may help to trace humans from different continents by JC genotyping.[27]

Drugs associated with reactivation

Since immunodeficiency causes this virus to progress to PML, immunosuppressants are contraindicated in those who are infected.[citation needed]

The boxed warning for the drug rituximab (Rituxan) includes a statement that Human polyomavirus 2 infection resulting in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and death has been reported in patients treated with the drug.[28]

The boxed warning for the drug natalizumab (Tysabri) includes a statement that Human polyomavirus 2 resulted in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy developing in three patients who received natalizumab in clinical trials. This is now one of the most common causes of PML.[29]

The boxed warning had been included for the drugs Tecfidera and Gilenya, both of which have had incidences of PML resulting in death.[citation needed]

The boxed warning was added on February 19, 2009, for the drug efalizumab (Raptiva) includes a statement that Human polyomavirus 2, resulting in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, developed in three patients who received efalizumab in clinical trials. The drug was pulled off the U.S. market because of the association with PML on April 10, 2009.[citation needed]

A boxed warning for brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) was issued by the FDA on January 13, 2011 after two cases of PML were reported, bringing the total number of associated cases to three.[30]

References

- ↑ Calvignac-Spencer, Sébastien (22 October 2015). "Revision on the family Polyomaviridae(76 species, four genera)" (in en). https://ictv.global/ictv/proposals/2015.015a-aaD.A.v2.Polyomaviridae_rev.pdf. "To rename the following taxon (or taxa): Current name Proposed name JC polyomavirus Human polyomavirus 2"

- ↑ ICTV 7th Report van Regenmortel, M.H.V., Fauquet, C.M., Bishop, D.H.L., Carstens, E.B., Estes, M.K., Lemon, S.M., Maniloff, J., Mayo, M.A., McGeoch, D.J., Pringle, C.R. and Wickner, R.B. (2000). Virus taxonomy. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego. p245 https://ictv.global/ictv/proposals/ICTV%207th%20Report.pdf

- ↑ "Tracing Males From Different Continents by Genotyping JC Polyomavirus in DNA From Semen Samples.". J Cell Physiol 232 (5): 982–985. 2017. doi:10.1002/jcp.25686. PMID 27859215.

- ↑ Zurhein, G; Chou, S. M. (1965). "Particles Resembling Papova Viruses in Human Cerebral Demyelinating Disease". Science 148 (3676): 1477–9. doi:10.1126/science.148.3676.1477. PMID 14301897. Bibcode: 1965Sci...148.1477R.

- ↑ Padgett BL, Walker DL et al. (1971). "Cultivation of papova-like virus from human brain with progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy". Lancet 1 (7712): 1257–60. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(71)91777-6. PMID 4104715.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ferenczy, MW; Marshall, LJ; Nelson, CD; Atwood, WJ; Nath, A; Khalili, K; Major, EO (July 2012). "Molecular biology, epidemiology, and pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, the JC virus-induced demyelinating disease of the human brain.". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25 (3): 471–506. doi:10.1128/CMR.05031-11. PMID 22763635.

- ↑ Monaco, M.C., Jensen, P.N., Hou, J., Durham, L.C. and Major, E.O. (1998). "Detection of JC virus DNA in human tonsil tissue: evidence for site of initial viral infection". J. Virol. 72 (12): 9918–23. doi:10.1128/JVI.72.12.9918-9923.1998. PMID 9811728.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bofill-Mas, S., Formiga-Cruz, M., Clemente-Casares, P., Calafell, F. and Girones, R. (2001). "Potential transmission of human polyomaviruses through the gastrointestinal tract after exposure to virions or viral DNA". J. Virol. 75 (21): 10290–9. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.21.10290-10299.2001. PMID 11581397.

- ↑ Ricciardiello, L., Laghi, L., Ramamirtham, P., Chang, C.L., Chang, D.K., Randolph, A.E. and Boland, C.R. (2000). "JC virus DNA sequences are frequently present in the human upper and lower gastrointestinal tract". Gastroenterology 119 (5): 1228–35. doi:10.1053/gast.2000.19269. PMID 11054380.

- ↑ Cornelissen, Cynthia Nau; Harvey, Richard A.; Fisher, Bruce D. (2012). "X. Opportunistic Infections of HIV: JC Virus (JCV)". Microbiology. Illustrated Reviews. 3. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 389. ISBN 978-1-60831-733-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=MKrm10WF3usC&pg=PA389.

- ↑ "Tracing Males From Different Continents by Genotyping JC Polyomavirus in DNA From Semen Samples.". J Cell Physiol 232 (5): 982–985. 2017. doi:10.1002/jcp.25686. PMID 27859215.

- ↑ "Footprints of BK and JC polyomaviruses in specimens from females affected by spontaneous abortion.". Hum Reprod 34 (3): 433–440. 2019. doi:10.1002/jcp.27490. PMID 30590693. https://academic.oup.com/humrep/article-abstract/34/3/433/5259177?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

- ↑ "Footprints of BK and JC polyomaviruses in specimens from females affected by spontaneous abortion.". Hum Reprod 34 (3): 433–440. 2019. doi:10.1002/jcp.27490. PMID 30590693. https://academic.oup.com/humrep/article-abstract/34/3/433/5259177?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

- ↑ Elphick, G.F., Querbes, W., Jordan, J.A., Gee, G.V., Eash, S., Manley, K., Dugan, A., Stanifer, M., Bhatnagar, A., Kroeze, W.K., Roth, B.L. and Atwood, W.J. (2004). "The human polyomavirus, JCV, uses serotonin receptors to infect cells". Science 306 (5700): 1380–3. doi:10.1126/science.1103492. PMID 15550673. Bibcode: 2004Sci...306.1380E. https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/articles/g158bk44g.

- ↑ White, F.A., 3rd., Ishaq, M., Stoner, G.L. and Frisque, R.J. (1992). "JC virus DNA is present in many human brain samples from patients without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy". J. Virol. 66 (10): 5726–4. doi:10.1128/JVI.66.10.5726-5734.1992. PMID 1326640.

- ↑ Marshall, Leslie J.; Dunham, Lisa; Major, Eugene O. (December 2010). "Transcription factor Spi-B binds unique sequences present in the tandem repeat promoter/enhancer of JC virus and supports viral activity". The Journal of General Virology 91 (Pt 12): 3042–3052. doi:10.1099/vir.0.023184-0. ISSN 0022-1317. PMID 20826618.

- ↑ Wollebo, Hassen S.; White, Martyn K.; Gordon, Jennifer; Berger, Joseph R.; Khalili, Kamel (April 2015). "Persistence and pathogenesis of the neurotropic polyomavirus JC". Annals of Neurology 77 (4): 560–570. doi:10.1002/ana.24371. ISSN 0364-5134. PMID 25623836.

- ↑ Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy in HIV at eMedicine

- ↑ Theodoropoulos, G., Panoussopoulos, D., Papaconstantinou, I., Gazouli, M., Perdiki, M., Bramis, J. and Lazaris, ACh. (2005). "Assessment of JC polyoma virus in colon neoplasms". Dis. Colon Rectum 48 (1): 86–91. doi:10.1007/s10350-004-0737-2. PMID 15690663.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Miskin DP and Koralnik IJ (2015). "Novel syndromes associated with JC virus infection of neurons and meningeal cells: no longer a gray area". Curr Opin Neurol 28 (3): 288–294. doi:10.1097/wco.0000000000000201. PMID 25887767.

- ↑ Wharton, Keith A.; Quigley, Catherine; Themeles, Marian; Dunstan, Robert W.; Doyle, Kathryn; Cahir-McFarland, Ellen; Wei, Jing; Buko, Alex et al. (18 May 2016). "JC Polyomavirus Abundance and Distribution in Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML) Brain Tissue Implicates Myelin Sheath in Intracerebral Dissemination of Infection". PLOS ONE 11 (5): e0155897. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155897. PMID 27191595. Bibcode: 2016PLoSO..1155897W.

- ↑ Agostini, H.T.; Ryschkewitsch, C.F.; Mory, R.; Singer, E.J.; Stoner, G.L. (1997). "JC Virus (JCV) genotypes in brain tissue from patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and in urine from controls without PML: increased frequency of JCV Type 2 in PML". J. Infect. Dis. 176 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1086/514010. PMID 9207343.

- ↑ Shackelton, L.A.; Rambaut, A.; Pybus, O.G.; Holmes, E.C. (2006). "JC Virus evolution and its association with human populations". Journal of Virology 80 (20): 9928–33. doi:10.1128/JVI.00441-06. PMID 17005670.

- ↑ Padgett, B.L.; Walker, D.L. (1973). "Prevalence of antibodies in human sera against JC virus, an isolate from a case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy". J. Infect. Dis. 127 (4): 467–470. doi:10.1093/infdis/127.4.467. PMID 4571704.

- ↑ Pavesi, A. (2005). "Utility of JC polyomavirus in tracing the pattern of human migrations dating to prehistoric times". J. Gen. Virol. 86 (Pt 5): 1315–26. doi:10.1099/vir.0.80650-0. PMID 15831942.

- ↑ "Tracing Males From Different Continents by Genotyping JC Polyomavirus in DNA From Semen Samples.". J Cell Physiol 232 (5): 982–985. 2017. doi:10.1002/jcp.25686. PMID 27859215.

- ↑ "Tracing Males From Different Continents by Genotyping JC Polyomavirus in DNA From Semen Samples.". J Cell Physiol 232 (5): 982–985. 2017. doi:10.1002/jcp.25686. PMID 27859215.

- ↑ gene.com/gene/products/information/pdf/rituxan-prescribing.pdf

- ↑ Major, Eugene O; Yousry, Tarek A; Clifford, David B (May 2018). "Pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and risks associated with treatments for multiple sclerosis: a decade of lessons learned". The Lancet Neurology 17 (5): 467–480. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30040-1. ISSN 1474-4422. PMID 29656742. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/10047630/.

- ↑ "Adcetris (brentuximab vedotin): Drug Safety Communication—Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy and Pulmonary Toxicity". U.S. FDA. https://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm287710.htm.

- Zu Rhein, G.M.; Chou, S.M. (1965). "Particles Resembling Papova Viruses in Human Cerebral Demyelinating Disease". Science 148 (3676): 1477–9. doi:10.1126/science.148.3676.1477. PMID 14301897. Bibcode: 1965Sci...148.1477R.

- Silverman, L.; Rubinstein, L.J. (1965). "Electron microscopic observations on a case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy". Acta Neuropathologica 5 (2): 215–224. doi:10.1007/bf00686519. PMID 5886201.

External links

- JC Brain infection MRI Diagnosis of PML

Wikidata ☰ Q24809461 entry

|