Biology:Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 | |

|---|---|

| |

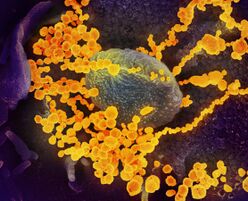

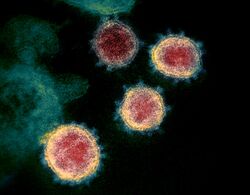

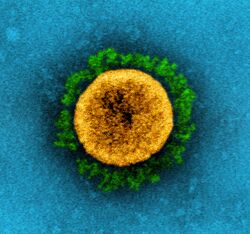

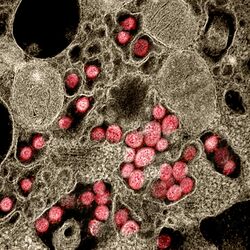

| Colourised transmission electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virions with visible coronae | |

| |

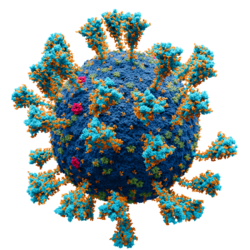

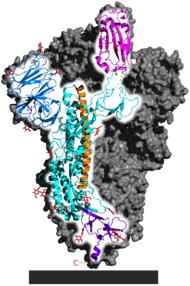

| Atomic model of the external structure of the SARS-CoV-2 virion. Each "ball" is an atom.[1] ● Blue: envelope ● Turquoise: spike glycoprotein (S) ● Red: envelope proteins (E) ● Green: membrane proteins (M) ● Orange: glycan | |

| Virus classification | |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Virus |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Riboviria |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Orthornavirae |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Pisuviricota |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Nidovirales |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Coronaviridae |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Betacoronavirus |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | Sarbecovirus |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | <div style="display:inline" class="script error: no such module "taxobox ranks".">Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus |

| Script error: No such module "Taxobox ranks".: | <div style="display:inline" class="script error: no such module "taxobox ranks".">Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| Notable variants | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2),[2] also known as the coronavirus, is the virus that causes COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), the respiratory illness responsible for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[3] The virus was previously referred to by its provisional name, 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV),[4][5][6][7] and has also been called human coronavirus 2019 (HCoV-19 or hCoV-19).[8][9][10][11] First identified in the city of Wuhan, Hubei, China, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January 2020, and a pandemic on 11 March 2020.[12][13] SARS‑CoV‑2 is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus[14] that is contagious in humans.[15] As described by the US National Institutes of Health, it is the successor to SARS-CoV-1, the virus that caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak.[16]

SARS‑CoV‑2 is a virus of the species severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV).[2] It is believed to have zoonotic origins and has close genetic similarity to bat coronaviruses, suggesting it emerged from a bat-borne virus.[9][17] Research is ongoing as to whether SARS‑CoV‑2 came directly from bats or indirectly through any intermediate hosts.[18] The virus shows little genetic diversity, indicating that the spillover event introducing SARS‑CoV‑2 to humans is likely to have occurred in late 2019.[19]

Epidemiological studies estimate that each infection results in an average of 2.4 to 3.4 new ones when no members of the community are immune and no preventive measures are taken.[20] The virus primarily spreads between people through close contact and via aerosols and respiratory droplets that are exhaled when talking, breathing, or otherwise exhaling, as well as those produced from coughs or sneezes.[21][22] It mainly enters human cells by binding to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a membrane protein that regulates the renin-angiotensin system.[23][24]

Terminology

During the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China, various names were used for the virus; some names used by different sources included "the coronavirus" or "Wuhan coronavirus".[25][26] In January 2020, the World Health Organization recommended "2019 novel coronavirus" (2019-nCov)[5][27] as the provisional name for the virus. This was in accordance with WHO's 2015 guidance[28] against using geographical locations, animal species, or groups of people in disease and virus names.[29][30]

On 11 February 2020, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses adopted the official name "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2" (SARS‑CoV‑2).[31] To avoid confusion with the disease SARS, the WHO sometimes refers to SARS‑CoV‑2 as "the COVID-19 virus" in public health communications[32][33] and the name HCoV-19 was included in some research articles.[8][9][10]

Infection and transmission

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Human-to-human transmission of SARS‑CoV‑2 was confirmed on 20 January 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.[15][34][35][36] Transmission was initially assumed to occur primarily via respiratory droplets from coughs and sneezes within a range of about 1.8 metres (6 ft).[37][38] Laser light scattering experiments suggest that speaking is an additional mode of transmission[39][40] and a far-reaching[41] and under-researched[42] one, indoors, with little air flow.[43][44] Other studies have suggested that the virus may be airborne as well, with aerosols potentially being able to transmit the virus.[45][46][47] During human-to-human transmission, between 200 and 800 infectious SARS‑CoV‑2 virions are thought to initiate a new infection.[48][49][50] If confirmed, aerosol transmission has biosafety implications because a major concern associated with the risk of working with emerging viruses in the laboratory is the generation of aerosols from various laboratory activities which are not immediately recognizable and may affect other scientific personnel.[51] Indirect contact via contaminated surfaces is another possible cause of infection.[52] Preliminary research indicates that the virus may remain viable on plastic (polypropylene) and stainless steel (AISI 304) for up to three days, but it does not survive on cardboard for more than one day or on copper for more than four hours.[10] The virus is inactivated by soap, which destabilizes its lipid bilayer.[53][54] Viral RNA has also been found in stool samples and semen from infected individuals.[55][56]

The degree to which the virus is infectious during the incubation period is uncertain, but research has indicated that the pharynx reaches peak viral load approximately four days after infection[57][58] or in the first week of symptoms and declines thereafter.[59] The duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding is generally between 3 and 46 days after symptom onset.[60]

A study by a team of researchers from the University of North Carolina found that the nasal cavity is seemingly the dominant initial site of infection, with subsequent aspiration-mediated virus-seeding into the lungs in SARS‑CoV‑2 pathogenesis.[61] They found that there was an infection gradient from high in proximal towards low in distal pulmonary epithelial cultures, with a focal infection in ciliated cells and type 2 pneumocytes in the airway and alveolar regions respectively.[61]

Studies have identified a range of animals—such as cats, ferrets, hamsters, non-human primates, minks, tree shrews, raccoon dogs, fruit bats, and rabbits—that are susceptible and permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection.[62][63][64] Some institutions have advised that those infected with SARS‑CoV‑2 restrict their contact with animals.[65][66]

Asymptomatic transmission

On 1 February 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that "transmission from asymptomatic cases is likely not a major driver of transmission".[67] One meta-analysis found that 17% of infections are asymptomatic, and asymptomatic individuals were 42% less likely to transmit the virus.[68]

However, an epidemiological model of the beginning of the outbreak in China suggested that "pre-symptomatic shedding may be typical among documented infections" and that subclinical infections may have been the source of a majority of infections.[69] That may explain how out of 217 on board a cruise liner that docked at Montevideo, only 24 of 128 who tested positive for viral RNA showed symptoms.[70] Similarly, a study of ninety-four patients hospitalized in January and February 2020 estimated patients shed the greatest amount of virus two to three days before symptoms appear and that "a substantial proportion of transmission probably occurred before first symptoms in the index case".[71]

Reinfection

There is uncertainty about reinfection and long-term immunity.[72] It is not known how common reinfection is, but reports have indicated that it is occurring with variable severity.[72]

The first reported case of reinfection was a 33-year-old man from Hong Kong who first tested positive on 26 March 2020, was discharged on 15 April 2020 after two negative tests, and tested positive again on 15 August 2020 (142 days later), which was confirmed by whole-genome sequencing showing that the viral genomes between the episodes belong to different clades.[73] The findings had the implications that herd immunity may not eliminate the virus if reinfection is not an uncommon occurrence and that vaccines may not be able to provide lifelong protection against the virus.[73]

Another case study described a 25-year-old man from Nevada who tested positive for SARS‑CoV‑2 on 18 April 2020 and on 5 June 2020 (separated by two negative tests). Since genomic analyses showed significant genetic differences between the SARS‑CoV‑2 variant sampled on those two dates, the case study authors determined this was a reinfection.[74] The man's second infection was symptomatically more severe than the first infection, but the mechanisms that could account for this are not known.[74]

Reservoir and origin

The first known infections from SARS‑CoV‑2 were discovered in Wuhan, China.[17] The original source of viral transmission to humans remains unclear, as does whether the virus became pathogenic before or after the spillover event.[9][19][75] Because many of the early infectees were workers at the Huanan Seafood Market,[76][77] it has been suggested that the virus might have originated from the market.[9][78] However, other research indicates that visitors may have introduced the virus to the market, which then facilitated rapid expansion of the infections.[19][79] A March 2021 WHO-convened report stated that human spillover via an intermediate animal host was the most likely explanation, with direct spillover from bats next most likely. Introduction through the food supply chain and the Huanan Seafood Market was considered another possible, but less likely, explanation.[80]

For a virus recently acquired through a cross-species transmission, rapid evolution is expected.[81] The mutation rate estimated from early cases of SARS-CoV-2 was of 6.54×10−4 per site per year.[80] Coronaviruses in general have high genetic plasticity,[82] but SARS-CoV-2's viral evolution is slowed by the RNA proofreading capability of its replication machinery.[83] For comparison, the viral mutation rate in vivo of SARS-CoV-2 has been found to be lower than that of influenza.[84]

Research into the natural reservoir of the virus that caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak has resulted in the discovery of many SARS-like bat coronaviruses, most originating in horseshoe bats. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that samples taken from Rhinolophus sinicus show a resemblance of 80% to SARS‑CoV‑2.[85][86][87] Phylogenetic analysis also indicates that a virus from Rhinolophus affinis, collected in Yunnan province and designated RaTG13, has a 96.1% resemblance to SARS‑CoV‑2.[17][88] This sequence was the closest known to SARS-CoV-2 at the time of its identification,[80] but it is not its direct ancestor.[89] Other closely-related sequences were also identified in samples from local bat populations.[90]

Bats are considered the most likely natural reservoir of SARS‑CoV‑2.[80][91] Differences between the bat coronavirus and SARS‑CoV‑2 suggest that humans may have been infected via an intermediate host;[78] although the source of introduction into humans remains unknown.[92][93]

Although the role of pangolins as an intermediate host was initially posited (a study published in July 2020 suggested that pangolins are an intermediate host of SARS‑CoV‑2-like coronaviruses[94][95]), subsequent studies have not substantiated their contribution to the spillover.[80] Evidence against this hypothesis includes the fact that pangolin virus samples are too distant to SARS-CoV-2: isolates obtained from pangolins seized in Guangdong were only 92% identical in sequence to the SARS‑CoV‑2 genome (matches above 90 percent may sound high, but in genomic terms it is a wide evolutionary gap[96]). In addition, despite similarities in a few critical amino acids,[97] pangolin virus samples exhibit poor binding to the human ACE2 receptor.[98]

Phylogenetics and taxonomy

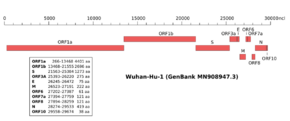

Genomic organisation of isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, the earliest sequenced sample of SARS-CoV-2 | |

| NCBI genome ID | 86693 |

|---|---|

| Genome size | 29,903 bases |

| Year of completion | 2020 |

| Genome browser (UCSC) | |

SARS‑CoV‑2 belongs to the broad family of viruses known as coronaviruses.[26] It is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) virus, with a single linear RNA segment. Coronaviruses infect humans, other mammals, including livestock and companion animals, and avian species.[99] Human coronaviruses are capable of causing illnesses ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS, fatality rate ~34%). SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh known coronavirus to infect people, after 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV, and the original SARS-CoV.[100]

Like the SARS-related coronavirus implicated in the 2003 SARS outbreak, SARS‑CoV‑2 is a member of the subgenus Sarbecovirus (beta-CoV lineage B).[101][102] Coronaviruses undergo frequent recombination.[103] The mechanism of recombination in unsegmented RNA viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 is generally by copy-choice replication, in which gene material switches from one RNA template molecule to another during replication.[104] SARS-CoV-2 RNA sequence is approximately 30,000 bases in length,[105] relatively long for a coronavirus (which in turn carry the largest genomes among all RNA families)[106] Its genome consists nearly entirely of protein-coding sequences, a trait shared with other coronaviruses.[103]

A distinguishing feature of SARS‑CoV‑2 is its incorporation of a polybasic site cleaved by furin,[97] which appears to be an important element enhancing its virulence.[107] It was suggested that the acquisition of the furin-cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 S protein was essential for zoonotic transfer to humans.[108] The furin protease recognizes the canonical peptide sequence RX[R/K]R↓X where the cleavage site is indicated by a down arrow and X is any amino acid.[109][110] In SARS-CoV-2 the recognition site is formed by the incorporated 12 codon nucleotide sequence CCT CGG CGG GCA which corresponds to the amino acid sequence PRRA.[111] This sequence is upstream of an arginine and serine which forms the S1/S2 cleavage site (PRRAR↓S) of the spike protein.[112] Although such sites are a common naturally-occurring feature of other viruses within the Subfamily Orthocoronavirinae,[111] it appears in few other viruses from the Beta-CoV genus,[113] and it is unique among members of its subgenus for such a site.[97]

Viral genetic sequence data can provide critical information about whether viruses separated by time and space are likely to be epidemiologically linked.[114] With a sufficient number of sequenced genomes, it is possible to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree of the mutation history of a family of viruses. By 12 January 2020, five genomes of SARS‑CoV‑2 had been isolated from Wuhan and reported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) and other institutions;[105][115] the number of genomes increased to 42 by 30 January 2020.[116] A phylogenetic analysis of those samples showed they were "highly related with at most seven mutations relative to a common ancestor", implying that the first human infection occurred in November or December 2019.[116] Examination of the topology of the phylogenetic tree at the start of the pandemic also found high similarities between human isolates.[117] As of 21 August 2021,[update] 3,422 SARS‑CoV‑2 genomes, belonging to 19 strains, sampled on all continents except Antarctica were publicly available.[118]

On 11 February 2020, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses announced that according to existing rules that compute hierarchical relationships among coronaviruses based on five conserved sequences of nucleic acids, the differences between what was then called 2019-nCoV and the virus from the 2003 SARS outbreak were insufficient to make them separate viral species. Therefore, they identified 2019-nCoV as a virus of Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus.[119]

In July 2020, scientists reported that a more infectious SARS‑CoV‑2 variant with spike protein variant G614 has replaced D614 as the dominant form in the pandemic.[120][121]

Coronavirus genomes and subgenomes encode six open reading frames (ORFs).[122] In October 2020, researchers discovered a possible overlapping gene named ORF3d, in the SARS‑CoV‑2 genome. It is unknown if the protein produced by ORF3d has any function, but it provokes a strong immune response. ORF3d has been identified before, in a variant of coronavirus that infects pangolins.[123][124]

Phylogenetic tree

Variants

There are many thousands of variants of SARS-CoV-2, which can be grouped into the much larger clades.[125] Several different clade nomenclatures have been proposed. Nextstrain divides the variants into five clades (19A, 19B, 20A, 20B, and 20C), while GISAID divides them into seven (L, O, V, S, G, GH, and GR).[126]

Several notable variants of SARS-CoV-2 emerged in late 2020. The World Health Organization has currently declared four variants of concern, which are as follows:[127]

- Alpha: Lineage B.1.1.7 emerged in the United Kingdom in September 2020, with evidence of increased transmissibility and virulence. Notable mutations include N501Y and P681H.

- An E484K mutation in some lineage B.1.1.7 virions has been noted and is also tracked by various public health agencies.

- Beta: Lineage B.1.351 emerged in South Africa in May 2020, with evidence of increased transmissibility and changes to antigenicity, with some public health officials raising alarms about its impact on the efficacy of some vaccines. Notable mutations include K417N, E484K and N501Y.

- Gamma: Lineage P.1 emerged in Brazil in November 2020, also with evidence of increased transmissibility and virulence, alongside changes to antigenicity. Similar concerns about vaccine efficacy have been raised. Notable mutations also include K417N, E484K and N501Y.

- Delta: Lineage B.1.617.2 emerged in India in October 2020. There is also evidence of increased transmissibility and changes to antigenicity.

Other notable variants include 6 other WHO-designated variants under investigation and Cluster 5, which emerged among mink in Denmark and resulted in a mink euthanasia campaign rendering it virtually extinct.[128]

Virology

Structure

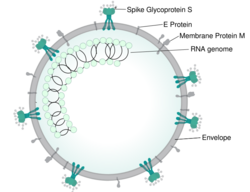

Each SARS-CoV-2 virion is 50–200 nanometres (2.0×10−6–7.9×10−6 in) in diameter.[77] Like other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 has four structural proteins, known as the S (spike), E (envelope), M (membrane), and N (nucleocapsid) proteins; the N protein holds the RNA genome, and the S, E, and M proteins together create the viral envelope.[129] Coronavirus S proteins are glycoproteins and also type I membrane proteins (membranes containing a single transmembrane domain oriented on the extracellular side).[108] They are divided into two functional parts (S1 and S2).[99] In SARS-CoV-2, the spike protein, which has been imaged at the atomic level using cryogenic electron microscopy,[130][131] is the protein responsible for allowing the virus to attach to and fuse with the membrane of a host cell;[129] specifically, its S1 subunit catalyzes attachment, the S2 subunit fusion.[132]

Genome

SARS-CoV-2 has a linear, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome about 30,000 bases long.[99] Its genome has a bias against cytosine (C) and guanine (G) nucleotides like other coronaviruses.[133] The genome has the highest composition of U (32.2%), followed by A (29.9%), and a similar composition of G (19.6%) and C (18.3%).[134] The nucleotide bias arises from the mutation of guanines and cytosines to adenosines and uracils, respectively.[135] The mutation of CG dinucleotides is thought to arise to avoid the zinc finger antiviral protein related defense mechanism of cells,[136] and to lower the energy to unbind the genome during replication and translation (adenosine and uracil base pair via two hydrogen bonds, cytosine and guanine via three).[135] The depletion of CG dinucleotides in its genome has led the virus to have a noticeable codon usage bias. For instance, arginine's six different codons have a relative synonymous codon usage of AGA (2.67), CGU (1.46), AGG (.81), CGC (.58), CGA (.29), and CGG (.19).[134] A similar codon usage bias trend is seen in other SARS–related coronaviruses.[137]

Replication cycle

Virus infections start when viral particles bind to host surface cellular receptors.[138] Protein modeling experiments on the spike protein of the virus soon suggested that SARS‑CoV‑2 has sufficient affinity to the receptor angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on human cells to use them as a mechanism of cell entry.[139] By 22 January 2020, a group in China working with the full virus genome and a group in the United States using reverse genetics methods independently and experimentally demonstrated that ACE2 could act as the receptor for SARS‑CoV‑2.[17][140][141][142] Studies have shown that SARS‑CoV‑2 has a higher affinity to human ACE2 than the original SARS virus.[130][143] SARS‑CoV‑2 may also use basigin to assist in cell entry.[144]

Initial spike protein priming by transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) is essential for entry of SARS‑CoV‑2.[23] The host protein neuropilin 1 (NRP1) may aid the virus in host cell entry using ACE2.[145] After a SARS‑CoV‑2 virion attaches to a target cell, the cell's TMPRSS2 cuts open the spike protein of the virus, exposing a fusion peptide in the S2 subunit, and the host receptor ACE2.[132] After fusion, an endosome forms around the virion, separating it from the rest of the host cell. The virion escapes when the pH of the endosome drops or when cathepsin, a host cysteine protease, cleaves it.[132] The virion then releases RNA into the cell and forces the cell to produce and disseminate copies of the virus, which infect more cells.[146]

SARS‑CoV‑2 produces at least three virulence factors that promote shedding of new virions from host cells and inhibit immune response.[129] Whether they include downregulation of ACE2, as seen in similar coronaviruses, remains under investigation (as of May 2020).[147]

Treatment and drug development

Very few drugs are known to effectively inhibit SARS‑CoV‑2. Masitinib is a clinically safe drug and was recently found to inhibit its main protease, 3CLpro and showed >200-fold reduction in viral titers in the lungs and nose in mice. However, it is not approved for the treatment of COVID-19 in humans as of August 2021.[148]

Epidemiology

Retrospective tests collected within the Chinese surveillance system revealed no clear indication of substantial unrecognized circulation of SARS‑CoV‑2 in Wuhan during the latter part of 2019.[80]

A meta-analysis from November 2020 estimated the basic reproduction number () of the virus to be between 2.39 and 3.44.[20] This means each infection from the virus is expected to result in 2.39 to 3.44 new infections when no members of the community are immune and no preventive measures are taken. The reproduction number may be higher in densely populated conditions such as those found on cruise ships.[149] Many forms of preventive efforts may be employed in specific circumstances to reduce the propagation of the virus.[122]

There have been about 96,000 confirmed cases of infection in mainland China.[150] While the proportion of infections that result in confirmed cases or progress to diagnosable disease remains unclear,[151] one mathematical model estimated that 75,815 people were infected on 25 January 2020 in Wuhan alone, at a time when the number of confirmed cases worldwide was only 2,015.[152] Before 24 February 2020, over 95% of all deaths from COVID-19 worldwide had occurred in Hubei province, where Wuhan is located.[153][154] As of 30 December 2021, the percentage had decreased to 0.059%.[150]

As of 30 December 2021, there have been 285,043,163 total confirmed cases of SARS‑CoV‑2 infection in the ongoing pandemic.[150] The total number of deaths attributed to the virus is 5,425,817.[150]

See also

- 3C-like protease (NS5)

References

- ↑ "Достоверно красиво: как мы сделали 3D-модель SARS-CoV-2" (in ru). N+1. 2021-07-29. https://nplus1.ru/blog/2021/07/29/sars-cov-2-model.

- ↑ "The Secret Life of a Coronavirus - An oily, 100-nanometer-wide bubble of genes has killed more than two million people and reshaped the world. Scientists don't quite know what to make of it.". 26 February 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/26/opinion/sunday/coronavirus-alive-dead.html.

- ↑ Surveillance case definitions for human infection with novel coronavirus (nCoV): interim guidance v1, January 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. January 2020. WHO/2019-nCoV/Surveillance/v2020.1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Healthcare Professionals: Frequently Asked Questions and Answers". 11 February 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/faq.html.

- ↑ "About Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". 11 February 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/index.html.

- ↑ "We Spoke to Six Americans with Coronavirus". 4 March 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/04/us/coronavirus-recovery.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Zoonotic origins of human coronavirus 2019 (HCoV-19 / SARS-CoV-2): why is this work important?". Zoological Research 41 (3): 213–219. May 2020. doi:10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.031. PMID 32314559.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine 26 (4): 450–452. April 2020. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. PMID 32284615.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1". The New England Journal of Medicine 382 (16): 1564–1567. April 2020. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2004973. PMID 32182409.

- ↑ "hCoV-19 Database". China National GeneBank. https://db.cngb.org/datamart/disease/DATAdis19/.

- ↑ "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ↑ "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 11 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ↑ "The Natural History, Pathobiology, and Clinical Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Infections". Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology 15 (3): 359–386. September 2020. doi:10.1007/s11481-020-09944-5. PMID 32696264.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster". Lancet 395 (10223): 514–523. February 2020. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. PMID 31986261.

- ↑ "New coronavirus stable for hours on surfaces" (in EN). NIH.gov. 17 March 2020. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/new-coronavirus-stable-hours-surfaces.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 "A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature 579 (7798): 270–273. March 2020. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. PMID 32015507. Bibcode: 2020Natur.579..270Z.

- ↑ Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 22 (Report). World Health Organization. 11 February 2020.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". Science. January 2020. doi:10.1126/science.abb0611.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Reproductive number of coronavirus: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on global level evidence". PLOS ONE 15 (11): e0242128. 11 November 2020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242128. PMID 33175914. Bibcode: 2020PLoSO..1542128B.

- ↑ "How Coronavirus Spreads ",Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ↑ "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): How is it transmitted? ",World Health Organization

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor". Cell 181 (2): 271–280.e8. April 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. PMID 32142651.

- ↑ "Virus-Receptor Interactions of Glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Human ACE2 Receptor". Cell Host & Microbe 28 (4): 586–601.e6. October 2020. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2020.08.004. PMID 32841605.

- ↑ "How Does Wuhan Coronavirus Compare with MERS, SARS and the Common Cold?". 22 January 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/01/22/798277557/how-does-wuhan-coronavirus-compare-to-mers-sars-and-the-common-cold.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "What you need to know about the novel coronavirus". Nature. January 2020. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00209-y. PMID 33483684.

- ↑ Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 10 (Report). World Health Organization. 30 January 2020.

- ↑ "World Health Organization Best Practices for the Naming of New Human Infectious Diseases". May 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/163636/WHO_HSE_FOS_15.1_eng.pdf.

- ↑ "Novel coronavirus named 'Covid-19': WHO". TODAYonline. https://www.todayonline.com/world/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-named-covid-19-who.

- ↑ "The coronavirus spreads racism against—and among—ethnic Chinese". The Economist. 17 February 2020. https://www.economist.com/china/2020/02/17/the-coronavirus-spreads-racism-against-and-among-ethnic-chinese.

- ↑ "Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) and the virus that causes it". World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it. "ICTV announced “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)” as the name of the new virus on 11 February 2020. This name was chosen because the virus is genetically related to the coronavirus responsible for the SARS outbreak of 2003. While related, the two viruses are different."

- ↑ "Why won't the WHO call the coronavirus by its name, SARS-CoV-2?". Quartz. 18 March 2020. https://qz.com/1820422/coronavirus-why-wont-who-use-the-name-sars-cov-2/.

- ↑ "Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) and the virus that causes it". World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it. "From a risk communications perspective, using the name SARS can have unintended consequences in terms of creating unnecessary fear for some populations. ... For that reason and others, WHO has begun referring to the virus as "the virus responsible for COVID-19" or "the COVID-19 virus" when communicating with the public. Neither of these designations is [sic] intended as replacements for the official name of the virus as agreed by the ICTV."

- ↑ "The epidemic of 2019-novel-coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia and insights for emerging infectious diseases in the future". Microbes and Infection 22 (2): 80–85. March 2020. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.002. PMID 32087334.

- ↑ "Trump's false claim that the WHO said the coronavirus was 'not communicable'". The Washington Post. 17 April 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/04/17/trumps-false-claim-that-who-said-coronavirus-was-not-communicable/.

- ↑ "China confirms human-to-human transmission of coronavirus". The Guardian. 21 January 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/20/coronavirus-spreads-to-beijing-as-china-confirms-new-cases.

- ↑ "How COVID-19 Spreads". 27 January 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/transmission.html.

- ↑ "How does coronavirus spread?". NBC News. 25 January 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/how-does-new-coronavirus-spread-n1121856.

- ↑ "Visualizing Speech-Generated Oral Fluid Droplets with Laser Light Scattering". The New England Journal of Medicine 382 (21): 2061–2063. May 2020. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2007800. PMID 32294341.

- ↑ "The airborne lifetime of small speech droplets and their potential importance in SARS-CoV-2 transmission". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117 (22): 11875–11877. June 2020. doi:10.1073/pnas.2006874117. PMID 32404416.

- ↑ "Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Theoretical Considerations and Available Evidence". JAMA 324 (5): 441–442. August 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12458. PMID 32749495. "Investigators have demonstrated that speaking and coughing produce a mixture of both droplets and aerosols in a range of sizes, that these secretions can travel together for up to 27 feet, that it is feasible for SARS-CoV-2 to remain suspended in the air and viable for hours, that SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be recovered from air samples in hospitals, and that poor ventilation prolongs the amount of time that aerosols remain airborne.".

- ↑ "The coronavirus pandemic and aerosols: Does COVID-19 transmit via expiratory particles?". Aerosol Science and Technology 54 (6): 635–638. 2 June 2020. doi:10.1080/02786826.2020.1749229. PMID 32308568. Bibcode: 2020AerST..54..635A. "It is unclear which of these mechanisms plays a key role in transmission of COVID-19. Much airborne disease research prior to the current pandemic has focused on ‘violent’ expiratory events like sneezing and coughing".

- ↑ "Talking is worse than coughing for spreading COVID-19 indoors" (in en). 21 January 2021. https://www.livescience.com/covid-19-spread-talking-coughing-indoors.html. "In one modeled scenario, the researchers found that after a short cough, the number of infectious particles in the air would quickly fall after 1 to 7 minutes; in contrast, after speaking for 30 seconds, only after 30 minutes would the number of infectious particles fall to similar levels; and a high number of particles were still suspended after one hour. In other words, a dose of virus particles capable of causing an infection would linger in the air much longer after speech than a cough. (In this modeled scenario, the same number of droplets were admitted during a 0.5-second cough as during the course of 30 seconds of speech.)"

- ↑ "Evolution of spray and aerosol from respiratory releases: theoretical estimates for insight on viral transmission". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 477 (2245): 20200584. January 2021. doi:10.1098/rspa.2020.0584. PMID 33633490. Bibcode: 2021RSPSA.47700584D.

- ↑ "239 Experts With One Big Claim: The Coronavirus Is Airborne – The W.H.O. has resisted mounting evidence that viral particles floating indoors are infectious, some scientists say. The agency maintains the research is still inconclusive.". The New York Times. 4 July 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/04/health/239-experts-with-one-big-claim-the-coronavirus-is-airborne.html.

- ↑ "We Need to Talk About Ventilation". The Atlantic. 30 July 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/07/why-arent-we-talking-more-about-airborne-transmission/614737/.

- ↑ "Mounting evidence suggests coronavirus is airborne - but health advice has not caught up". Nature 583 (7817): 510–513. July 2020. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02058-1. PMID 32647382. Bibcode: 2020Natur.583..510L.

- ↑ "Genomic epidemiology of superspreading events in Austria reveals mutational dynamics and transmission properties of SARS-CoV-2". Science Translational Medicine 12 (573): eabe2555. December 2020. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.abe2555. PMID 33229462.

- ↑ "Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19". Nature Medicine 26 (5): 672–675. May 2020. doi:10.1021/acs.chas.0c00035. PMID 32296168.

- ↑ "Development of a dose-response model for SARS coronavirus". Risk Analysis 30 (7): 1129–38. July 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01427.x. PMID 20497390.

- ↑ "Laboratory biosafety for handling emerging viruses". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 7 (5): 483–491. May 2017. doi:10.1016/j.apjtb.2017.01.020. PMID 32289025.

- ↑ "Getting your workplace ready for COVID-19". 27 February 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/getting-workplace-ready-for-covid-19.pdf.

- ↑ "Why the Coronavirus Has Been So Successful". 20 March 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2020/03/biography-new-coronavirus/608338/.

- ↑ "Why soap is preferable to bleach in the fight against coronavirus". 18 March 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/03/why-soap-preferable-bleach-fight-against-coronavirus/.

- ↑ "First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States". The New England Journal of Medicine 382 (10): 929–936. March 2020. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. PMID 32004427.

- ↑ "Clinical Characteristics and Results of Semen Tests Among Men With Coronavirus Disease 2019". JAMA Network Open 3 (5): e208292. May 2020. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292. PMID 32379329.

- ↑ "Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019". Nature 581 (7809): 465–469. May 2020. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. PMID 32235945. Bibcode: 2020Natur.581..465W.

- ↑ "Study claiming new coronavirus can be transmitted by people without symptoms was flawed". Science. February 2020. doi:10.1126/science.abb1524.

- ↑ "Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases 20 (5): 565–574. May 2020. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. PMID 32213337.

- ↑ "Case Study: Prolonged Infectious SARS-CoV-2 Shedding from an Asymptomatic Immunocompromised Individual with Cancer". Cell 183 (7): 1901–1912.e9. December 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.049. PMID 33248470.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics Reveals a Variable Infection Gradient in the Respiratory Tract". Cell 182 (2): 429–446.e14. July 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.042. PMID 32526206.

- ↑ "Zooanthroponotic potential of SARS-CoV-2 and implications of reintroduction into human populations". Cell Host & Microbe 29 (2): 160–164. February 2021. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2021.01.004. PMID 33539765.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers on the COVID-19: OIE – World Organisation for Animal Health". https://www.oie.int/en/scientific-expertise/specific-information-and-recommendations/questions-and-answers-on-2019novel-coronavirus/.

- ↑ "Bronx Zoo Tiger Is Sick with the Coronavirus". The New York Times. 6 April 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/nyregion/bronx-zoo-tiger-coronavirus.html.

- ↑ "USDA Statement on the Confirmation of COVID-19 in a Tiger in New York". 5 April 2020. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/news/sa_by_date/sa-2020/ny-zoo-covid-19.

- ↑ "If You Have Animals—Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (in en-us). 13 April 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/animals.html.

- ↑ Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 12 (Report). World Health Organization. 1 February 2020.

- ↑ "What the data say about asymptomatic COVID infections". Nature 587 (7835): 534–535. November 2020. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03141-3. PMID 33214725. Bibcode: 2020Natur.587..534N.

- ↑ "Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)". Science 368 (6490): 489–493. May 2020. doi:10.1126/science.abb3221. PMID 32179701. Bibcode: 2020Sci...368..489L.

- ↑ Daily Telegraph, Thursday 28 May 2020, page 2 column 1, which refers to the medical journal Thorax; Thorax May 2020 article COVID-19: in the footsteps of Ernest Shackleton

- ↑ "Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19". Nature Medicine 26 (5): 672–675. May 2020. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. PMID 32296168.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 "Coronavirus reinfections: three questions scientists are asking". Nature 585 (7824): 168–169. September 2020. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02506-y. PMID 32887957.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "COVID-19 re-infection by a phylogenetically distinct SARS-coronavirus-2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing". Clinical Infectious Diseases: ciaa1275. August 2020. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1275. PMID 32840608.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 "Genomic evidence for reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: a case study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases 21 (1): 52–58. January 2021. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30764-7. PMID 33058797.

- ↑ "We're still not sure where the Wuhan coronavirus really came from". 28 January 2020. https://www.popsci.com/story/health/wuhan-coronavirus-china-wet-market-wild-animal/.

- ↑ "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". Lancet 395 (10223): 497–506. February 2020. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. PMID 31986264.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". Lancet 395 (10223): 507–513. February 2020. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. PMID 32007143.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 "Mystery deepens over animal source of coronavirus". Nature 579 (7797): 18–19. March 2020. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00548-w. PMID 32127703. Bibcode: 2020Natur.579...18C.

- ↑ "Decoding the evolution and transmissions of the novel pneumonia coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2 / HCoV-19) using whole genomic data". Zoological Research 41 (3): 247–257. May 2020. doi:10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.022. PMID 32351056.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 80.3 80.4 80.5 Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). 24 February 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ↑ "A selective sweep in the Spike gene has driven SARS-CoV-2 human adaptation". Cell 184 (17): 4392–4400.e4. August 2021. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.007. PMID 34289344.

- ↑ "Novel human coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A lesson from animal coronaviruses". Veterinary Microbiology 244: 108693. May 2020. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108693. PMID 32402329.

- ↑ "Coronavirus RNA Proofreading: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Targeting [published correction appears in Mol Cell. 2020 Dec 17;80(6):1136-1138"]. Molecular Cell 79 (5): 710–727. August 2020. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2020.07.027. PMID 32853546.

- ↑ Tao, Kaiming; Tzou, Philip L.; Nouhin, Janin; Gupta, Ravindra K.; de Oliveira, Tulio; Kosakovsky Pond, Sergei L.; Fera, Daniela; Shafer, Robert W. (17 September 2021). "The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants". Nature Reviews Genetics. doi:10.1038/s41576-021-00408-x.

- ↑ "The 2019-new coronavirus epidemic: Evidence for virus evolution". Journal of Medical Virology 92 (4): 455–459. April 2020. doi:10.1002/jmv.25688. PMID 31994738.

- ↑ Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate bat-SL-CoVZC45, complete genome. 15 February 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MG772933. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ↑ Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate bat-SL-CoVZXC21, complete genome. 15 February 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MG772934. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ↑ "Bat coronavirus isolate RaTG13, complete genome". 10 February 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/1802633852.

- ↑ "The 'Occam's Razor Argument' Has Not Shifted in Favor of a Lab Leak". Snopes. https://www.snopes.com/news/2021/07/16/lab-leak-evidence/.

- ↑ "Identification of novel bat coronaviruses sheds light on the evolutionary origins of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses". Cell 184 (17): 4380–4391.e14. August 2021. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.008. PMID 34147139.

- ↑ "Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding". Lancet 395 (10224): 565–574. February 2020. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. PMID 32007145.

- ↑ The Basics of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission. Vancouver, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health (NCCEH). 21 March 2021. ISBN 978-1-988234-54-0. https://ncceh.ca/documents/evidence-review/basics-sars-cov-2-transmission. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ "The Origins of SARS-CoV-2: A Critical Review". Cell. August 2021. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017. PMID 34480864.

- ↑ "Isolation of SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins". Nature 583 (7815): 286–289. July 2020. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2313-x. PMID 32380510. Bibcode: 2020Natur.583..286X.

- ↑ "The Potential Intermediate Hosts for SARS-CoV-2". Frontiers in Microbiology 11: 580137. 2020. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.580137. PMID 33101254.

- ↑ "Why it's so tricky to trace the origin of COVID-19" (in en). Science (National Geographic). 10 September 2021. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/why-its-so-tricky-to-trace-the-origin-of-covid-19.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 "Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 19 (3): 141–154. March 2021. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. PMID 33024307.

- ↑ "Evolution patterns of SARS-CoV-2: Snapshot on its genome variants". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 538: 88–91. January 2021. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.10.102. PMID 33199021.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 "Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 19 (3): 155–170. March 2021. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. PMID 33116300.

- ↑ "A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019". The New England Journal of Medicine 382 (8): 727–733. February 2020. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. PMID 31978945.

- ↑ "Phylogeny of SARS-like betacoronaviruses". https://nextstrain.org/groups/blab/sars-like-cov.

- ↑ "Global Epidemiology of Bat Coronaviruses". Viruses 11 (2): 174. February 2019. doi:10.3390/v11020174. PMID 30791586.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 "On the origin and evolution of SARS-CoV-2". Experimental & Molecular Medicine 53 (4): 537–547. April 2021. doi:10.1038/s12276-021-00604-z. PMID 33864026.

- ↑ Jackson, Ben; Boni, Maciej F.; Bull, Matthew J.; Colleran, Amy; Colquhoun, Rachel M.; Darby, Alistair C.; Haldenby, Sam; Hill, Verity et al. (August 2021). "Generation and transmission of inter-lineage recombinants in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic". Cell. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.014.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 "CoV2020". https://platform.gisaid.org/epi3/start/CoV2020.

- ↑ "The Architecture of SARS-CoV-2 Transcriptome". Cell 181 (4): 914–921.e10. May 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.011. PMID 32330414.

- ↑ "Lessons learned 1 year after SARS-CoV-2 emergence leading to COVID-19 pandemic". Emerging Microbes & Infections 10 (1): 507–535. December 2021. doi:10.1080/22221751.2021.1898291. PMID 33666147.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Jackson, Cody B.; Farzan, Michael; Chen, Bing; Choe, Hyeryun (5 October 2021). "Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. doi:10.1038/s41580-021-00418-x.

- ↑ "Furin-mediated protein processing in infectious diseases and cancer". Clinical & Translational Immunology 8 (8): e1073. 2019. doi:10.1002/cti2.1073. PMID 31406574.

- ↑ "Structure of Furin Protease Binding to SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein and Implications for Potential Targets and Virulence". The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 11 (16): 6655–6663. August 2020. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01698. PMID 32787225.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 "The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade". Antiviral Research 176: 104742. April 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. PMID 32057769.

- ↑ "Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak". Current Biology 30 (7): 1346–1351.e2. April 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. PMID 32197085.

- ↑ "Furin cleavage sites naturally occur in coronaviruses". Stem Cell Research 50: 102115. December 2020. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2020.102115. PMID 33340798.

- ↑ "The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in Europe and North America". Science 370 (6516): 564–570. October 2020. doi:10.1126/science.abc8169. PMID 32912998.

- ↑ "Initial genome release of novel coronavirus". 11 January 2020. http://virological.org/t/initial-genome-release-of-novel-coronavirus/319.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "Genomic analysis of nCoV spread: Situation report 2020-01-30". https://nextstrain.org/narratives/ncov/sit-rep/2020-01-30.

- ↑ "COVID-19: Epidemiology, Evolution, and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives". Trends in Molecular Medicine 26 (5): 483–495. May 2020. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2020.02.008. PMID 32359479.

- ↑ "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus - Global subsampling". 25 October 2021. https://nextstrain.org/ncov/global.

- ↑ Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (April 2020). "The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2". Nature Microbiology 5 (4): 536–544. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. PMID 32123347.

- ↑ "New, more infectious strain of COVID-19 now dominates global cases of virus: study" (in en). medicalxpress.com. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-07-infectious-strain-covid-dominates-global.html.

- ↑ "Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus" (in English). Cell 182 (4): 812–827.e19. August 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. PMID 32697968.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 "Coronavirus Disease 2019-COVID-19". Clinical Microbiology Reviews 33 (4). September 2020. doi:10.1128/CMR.00028-20. PMID 32580969.

- ↑ "Scientists Just Found a Mysteriously Hidden 'Gene Within a Gene' in SARS-CoV-2". ScienceAlert. 11 November 2020. https://www.sciencealert.com/scientists-find-mysterious-gene-within-gene-hidden-in-the-coronavirus-genome.

- ↑ "Dynamically evolving novel overlapping gene as a factor in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic". eLife 9. October 2020. doi:10.7554/eLife.59633. PMID 33001029. PMC 7655111. https://elifesciences.org/articles/59633. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ "Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes". Bulletin of the World Health Organization 98 (7): 495–504. July 2020. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.253591. PMID 32742035. "We detected in total 65776 variants with 5775 distinct variants.".

- ↑ "Geographical and temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 clades in the WHO European Region, January to June 2020". Euro Surveillance 25 (32). August 2020. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.32.2001410. PMID 32794443.

- ↑ World Health Organization (31 May 2021). "Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants". https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/.

- ↑ "SARS-CoV-2 mink-associated variant strain – Denmark". 3 December 2020. https://www.who.int/csr/don/03-december-2020-mink-associated-sars-cov2-denmark/en/.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 129.2 "Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods". Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 10 (5): 766–788. May 2020. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. PMID 32292689.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 "Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation". Science 367 (6483): 1260–1263. March 2020. doi:10.1126/science.abb2507. PMID 32075877. Bibcode: 2020Sci...367.1260W.

- ↑ "Scientists Create Atomic-Level Image of the New Coronavirus's Potential Achilles Heel". 19 February 2020. https://gizmodo.com/scientists-create-atomic-level-image-of-the-new-coronav-1841795715.

- ↑ "From SARS and MERS CoVs to SARS-CoV-2: Moving toward more biased codon usage in viral structural and nonstructural genes". Journal of Medical Virology 92 (6): 660–666. June 2020. doi:10.1002/jmv.25754. PMID 32159237.

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 "Characterization of codon usage pattern in SARS-CoV-2". Virology Journal 17 (1): 138. September 2020. doi:10.1186/s12985-020-01395-x. PMID 32928234.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 "Human SARS-CoV-2 has evolved to reduce CG dinucleotide in its open reading frames". Scientific Reports 10 (1): 12331. July 2020. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69342-y. PMID 32704018. Bibcode: 2020NatSR..1012331W.

- ↑ "Evidence for Strong Mutation Bias toward, and Selection against, U Content in SARS-CoV-2: Implications for Vaccine Design". Molecular Biology and Evolution 38 (1): 67–83. January 2021. doi:10.1093/molbev/msaa188. PMID 32687176.

- ↑ "Multivariate analyses of codon usage of SARS-CoV-2 and other betacoronaviruses". Virus Evolution 6 (1): veaa032. January 2020. doi:10.1093/ve/veaa032. PMID 32431949.

- ↑ "Structural and Functional Basis of SARS-CoV-2 Entry by Using Human ACE2". Cell 181 (4): 894–904.e9. May 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. PMID 32275855.

- ↑ "Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission". Science China Life Sciences 63 (3): 457–460. March 2020. doi:10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. PMID 32009228.

- ↑ "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses". Nature Microbiology 5 (4): 562–569. April 2020. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. PMID 32094589.

- ↑ "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses". Nature Microbiology 5 (4): 562–569. April 2020. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. PMID 32094589.

- ↑ "Genomic Characterization of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus". The New England Journal of Medicine. https://www.jwatch.org/na50823/2020/02/06/genomic-characterization-2019-novel-coronavirus. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Novel coronavirus structure reveals targets for vaccines and treatments". 2 March 2020. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/novel-coronavirus-structure-reveals-targets-vaccines-treatments.

- ↑ "CD147-spike protein is a novel route for SARS-CoV-2 infection to host cells". Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 5 (1): 283. December 2020. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-00426-x. PMID 33277466.

- ↑ "ACE2: Evidence of role as entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2 and implications in comorbidities". eLife 9. November 2020. doi:10.7554/eLife.61390. PMID 33164751.

- ↑ "Anatomy of a Killer: Understanding SARS-CoV-2 and the drugs that might lessen its power". The Economist. 12 March 2020. https://www.economist.com/briefing/2020/03/12/understanding-sars-cov-2-and-the-drugs-that-might-lessen-its-power. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ↑ "BMJ Best Practice: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (in en). 22 May 2020. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/3000168/pdf/3000168.pdf.

- ↑ "Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2". Science 373 (6557): 931–936. August 2021. doi:10.1126/science.abg5827. PMID 34285133.

- ↑ "COVID-19 outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: estimating the epidemic potential and effectiveness of public health countermeasures". Journal of Travel Medicine 27 (3). May 2020. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa030. PMID 32109273.

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 150.2 150.3 "COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU)". Johns Hopkins University. https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6.

- ↑ "Limited data on coronavirus may be skewing assumptions about severity". STAT. 30 January 2020. https://www.statnews.com/2020/01/30/limited-data-may-skew-assumptions-severity-coronavirus-outbreak/.

- ↑ "Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study". Lancet 395 (10225): 689–697. February 2020. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. PMID 32014114.

- ↑ "Coronavirus deaths leap in China as countries struggle to evacuate citizens". The Guardian. 30 January 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/30/coronavirus-deaths-leap-in-china-as-countries-struggle-to-evacuate-citizens.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: China to repay Africa in safeguarding public health". The Sun. 25 February 2020. https://www.sunnewsonline.com/coronavirus-china-to-repay-africa-in-safeguarding-public-health/.

Further reading

- "SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by the numbers". eLife 9. April 2020. doi:10.7554/eLife.57309. PMID 32228860. Bibcode: 2020arXiv200312886B.

- "The Novel Coronavirus - A Snapshot of Current Knowledge". Microbial Biotechnology 13 (3): 607–612. May 2020. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.13557. PMID 32144890.

- "Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19)". StatPearls. January 2020. PMID 32150360. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776/. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in suspected human cases (Report). World Health Organization. 2 March 2020.

- "[Comment The COVID‑19 pandemic as a scientific and social challenge in the 21st century"]. Molecular Medicine Reports 22 (4): 3035–3048. October 2020. doi:10.3892/mmr.2020.11393. PMID 32945405.

External links

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". 11 February 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

- "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic". https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- "SARS-CoV-2 (Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) Sequences". https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/sars-cov-2-seqs/.

- "COVID-19 Resource Centre". https://www.thelancet.com/coronavirus.

- "Coronavirus (Covid-19)". https://www.nejm.org/coronavirus.

- "Covid-19: Novel Coronavirus Outbreak". https://novel-coronavirus.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/.

- "SARS-CoV-2". https://www.viprbrc.org/brc/home.spg?decorator=corona_ncov.

- "SARS-CoV-2 related protein structures". http://www.rcsb.org/news?year=2020&article=5e3c4bcba5007a04a313edcc.

Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Portal/images/aliases' not found.

| Classification |

|---|

Wikidata ☰ Q82069695 entry