Medicine:Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis |

| |

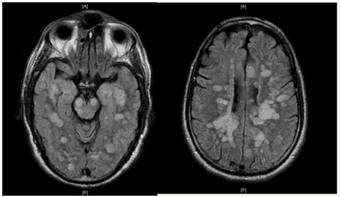

| Fulminating ADEM showing many lesions. The patient survived, but remained in a persistent vegetative state | |

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), or acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis, is a rare autoimmune disease marked by a sudden, widespread attack of inflammation in the brain and spinal cord. As well as causing the brain and spinal cord to become inflamed, ADEM also attacks the nerves of the central nervous system and damages their myelin insulation, which, as a result, destroys the white matter. The cause is often a trigger such as from viral infection or vaccinations.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

ADEM's symptoms resemble the symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS), so the disease itself is sorted into the classification of the multiple sclerosis borderline diseases. However, ADEM has several features that distinguish it from MS.[7] Unlike MS, ADEM occurs usually in children and is marked with rapid fever, although adolescents and adults can get the disease too. ADEM consists of a single flare-up whereas MS is marked with several flare-ups (or relapses), over a long period of time. Relapses following ADEM are reported in up to a quarter of patients, but the majority of these 'multiphasic' presentations following ADEM likely represent MS.[8] ADEM is also distinguished by a loss of consciousness, coma and death, which is very rare in MS, except in severe cases.

It affects about 8 per 1,000,000 people per year.[9] Although it occurs in all ages, most reported cases are in children and adolescents, with the average age around 5 to 8 years old.[10][11][12][13] The disease affects males and females almost equally.[14] ADEM shows seasonal variation with higher incidence in winter and spring months which may coincide with higher viral infections during these months.[13] The mortality rate may be as high as 5%; however, full recovery is seen in 50 to 75% of cases with increase in survival rates up to 70 to 90% with figures including minor residual disability as well.[15] The average time to recover from ADEM flare-ups is one to six months.

ADEM produces multiple inflammatory lesions in the brain and spinal cord, particularly in the white matter. Usually these are found in the subcortical and central white matter and cortical gray-white junction of both cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord,[16] but periventricular white matter and gray matter of the cortex, thalami and basal ganglia may also be involved.

When a person has more than one demyelinating episode of ADEM, the disease is then called recurrent disseminated encephalomyelitis[17] or multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis[18] (MDEM). Also, a fulminant course in adults has been described.[19]

Signs and symptoms

ADEM has an abrupt onset and a monophasic course. Symptoms usually begin 1–3 weeks after infection. Major symptoms include fever, headache, nausea and vomiting, confusion, vision impairment, drowsiness, seizures and coma. Although initially the symptoms are usually mild, they worsen rapidly over the course of hours to days, with the average time to maximum severity being about four and a half days.[20] Additional symptoms include hemiparesis, paraparesis, and cranial nerve palsies.[21]

ADEM in COVID-19

Neurological symptoms were the main presentation of COVID-19, which did not correlate with the severity of respiratory symptoms. The high incidence of ADEM with hemorrhage is striking. Brain inflammation is likely caused by an immune response to the disease rather than neurotropism. CSF analysis was not indicative of an infectious process, neurological impairment was not present in the acute phase of the infection, and neuroimaging findings were not typical of classical toxic and metabolic disorders. The finding of bilateral periventricular relatively asymmetrical lesions allied with deep white matter involvement, that may also be present in cortical gray-white matter junction, thalami, basal ganglia, cerebellum, and brainstem suggests an acute demyelination process.[22] Additionally, hemorrhagic white matter lesions, clusters of macrophages related to axonal injury and ADEM-like appearance were also found in subcortical white matter.[23]

Causes

Since the discovery of the anti-MOG specificity against multiple sclerosis diagnosis[24] it is considered that ADEM is one of the possible clinical causes of anti-MOG associated encephalomyelitis.[25]

About how the anti-MOG antibodies appear in the patients serum there are several theories:

- A preceding antigenic challenge can be identified in approximately two-thirds of people.[14] Some viral infections thought to induce ADEM include influenza virus, dengue,[26] enterovirus, measles,[27] mumps, rubella, varicella zoster, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, hepatitis A, coxsackievirus and COVID-19.[22][28] Bacterial infections include Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Borrelia burgdorferi, Leptospira, and beta-hemolytic Streptococci.[29]

- Exposure to vaccines: The only vaccine proven related to ADEM is the Semple form of the rabies vaccine, but hepatitis B, pertussis, diphtheria, measles, mumps, rubella, pneumococcus, varicella, influenza, Japanese encephalitis, and polio vaccines have all been implicated. The majority of the studies that correlate vaccination with ADEM onset use only small samples or are case studies.[citation needed] Large-scale epidemiological studies (e.g., of MMR vaccine or smallpox vaccine) do not show increased risk of ADEM following vaccination.[9][30][31][32][20][33][34][35][36][37][38] An upper bound for the risk of ADEM from measles vaccination, if it exists, can be estimated to be 10 per million,[39] which is far lower than the risk of developing ADEM from an actual measles infection, which is about 1 per 1,000 cases. For a rubella infection, the risk is 1 per 5,000 cases.[33][40] Some early vaccines, later shown to have been contaminated with host animal CNS tissue, had ADEM incidence rates as high as 1 in 600.[30]

- In rare cases, ADEM seems to follow from organ transplantation.[20]

Diagnosis

The term ADEM has been inconsistently used at different times.[41] Currently, the commonly accepted international standard for the clinical case definition is the one published by the International Pediatric MS Study Group, revision 2007.[42]

Given that the definition is clinical, it is currently unknown if all the cases of ADEM are positive for anti-MOG autoantibody; in any case, it appears to be strongly related to ADEM diagnosis.[25]

Differential diagnosis

Multiple sclerosis

While ADEM and MS both involve autoimmune demyelination, they differ in many clinical, genetic, imaging, and histopathological aspects.[14][43] Some authors consider MS and its borderline forms to constitute a spectrum, differing only in chronicity, severity, and clinical course,[44][45] while others consider them discretely different diseases.[6]

Typically, ADEM appears in children following an antigenic challenge and remains monophasic. Nevertheless, ADEM does occur in adults,[8][12] and can also be clinically multiphasic.[46]

Problems for differential diagnosis increase due to the lack of agreement for a definition of multiple sclerosis.[47] If MS were defined only by the separation in time and space of the demyelinating lesions as McDonald did,[48] it would not be enough to make a difference, as some cases of ADEM satisfy these conditions. Therefore, some authors propose to establish the dividing line as the shape of the lesions around the veins, being therefore "perivenous vs. confluent demyelination".[47][49]

The pathology of ADEM is very similar to that of MS with some differences. The pathological hallmark of ADEM is perivenous inflammation with limited "sleeves of demyelination".[50][14] Nevertheless, MS-like plaques (confluent demyelination) can appear[51]

Plaques in the white matter in MS are sharply delineated, while the glial scar in ADEM is smooth. Axons are better preserved in ADEM lesions. Inflammation in ADEM is widely disseminated and ill-defined, and finally, lesions are strictly perivenous, while in MS they are disposed around veins, but not so sharply.[52]

Nevertheless, the co-occurrence of perivenous and confluent demyelination in some individuals suggests pathogenic overlap between acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis and misclassification even with biopsy[49] or even postmortem[51] ADEM in adults can progress to MS[12]

Multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis

When the person has more than one demyelinating episode of ADEM, the disease is then called recurrent disseminated encephalomyelitis or multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis[18] (MDEM).

It has been found that anti-MOG auto-antibodies are related to this kind of ADEM[53]

Another variant of ADEM in adults has been described, also related to anti-MOG auto-antibodies, has been named fulminant disseminated encephalomyelitis, and it has been reported to be clinically ADEM, but showing MS-like lesions on autopsy.[19] It has been classified inside the anti-MOG associated inflammatory demyelinating diseases.[54]

Acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis

Acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (AHL, or AHLE), acute hemorrhagic encephalomyelitis (AHEM), acute necrotizing hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (ANHLE), Weston-Hurst syndrome, or Hurst's disease, is a hyperacute and frequently fatal form of ADEM. AHL is relatively rare (less than 100 cases have been reported in the medical literature (As of 2006)),[55] it is seen in about 2% of ADEM cases,[20] and is characterized by necrotizing vasculitis of venules and hemorrhage, and edema.[56] Death is common in the first week[57] and overall mortality is about 70%,[55] but increasing evidence points to favorable outcomes after aggressive treatment with corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, cyclophosphamide, and plasma exchange.[29] About 70% of survivors show residual neurological deficits,[56] but some survivors have shown surprisingly little deficit considering the extent of the white matter affected.[57]

This disease has been occasionally associated with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, malaria,[58] sepsis associated with immune complex deposition, methanol poisoning, and other underlying conditions. Also anecdotal association with MS has been reported[59]

Laboratory studies that support diagnosis of AHL are: peripheral leukocytosis, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis associated with normal glucose and increased protein. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), lesions of AHL typically show extensive T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) white matter hyperintensities with areas of hemorrhages, significant edema, and mass effect.[60]

Treatment

No controlled clinical trials have been conducted on ADEM treatment, but aggressive treatment aimed at rapidly reducing inflammation of the CNS is standard. The widely accepted first-line treatment is high doses of intravenous corticosteroids,[61] such as methylprednisolone or dexamethasone, followed by 3–6 weeks of gradually lower oral doses of prednisolone. Patients treated with methylprednisolone have shown better outcomes than those treated with dexamethasone.[20] Oral tapers of less than three weeks duration show a higher chance of relapsing,[11][18] and tend to show poorer outcomes.[citation needed] Other anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapies have been reported to show beneficial effect, such as plasmapheresis, high doses of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg),[61][62] mitoxantrone and cyclophosphamide. These are considered alternative therapies, used when corticosteroids cannot be used or fail to show an effect.[citation needed]

There is some evidence to suggest that patients may respond to a combination of methylprednisolone and immunoglobulins if they fail to respond to either separately[63] In a study of 16 children with ADEM, 10 recovered completely after high-dose methylprednisolone, one severe case that failed to respond to steroids recovered completely after IV Ig; the five most severe cases – with ADAM and severe peripheral neuropathy – were treated with combined high-dose methylprednisolone and immunoglobulin, two remained paraplegic, one had motor and cognitive handicaps, and two recovered.[61] A recent review of IVIg treatment of ADEM (of which the previous study formed the bulk of the cases) found that 70% of children showed complete recovery after treatment with IVIg, or IVIg plus corticosteroids.[64] A study of IVIg treatment in adults with ADEM showed that IVIg seems more effective in treating sensory and motor disturbances, while steroids seem more effective in treating impairments of cognition, consciousness and rigor.[62] This same study found one subject, a 71-year-old man who had not responded to steroids, that responded to an IVIg treatment 58 days after disease onset.[citation needed]

Prognosis

Full recovery is seen in 50 to 70% of cases, ranging to 70 to 90% recovery with some minor residual disability (typically assessed using measures such as mRS or EDSS), average time to recover is one to six months.[15] The mortality rate may be as high as 5–10%.[15][65] Poorer outcomes are associated with unresponsiveness to steroid therapy, unusually severe neurological symptoms, or sudden onset. Children tend to have more favorable outcomes than adults, and cases presenting without fevers tend to have poorer outcomes. The latter effect may be due to either protective effects of fever, or that diagnosis and treatment is sought more rapidly when fever is present. [66]

ADEM can progress to MS. It will be considered MS if some lesions appear in different times and brain areas[67]

Motor deficits

Residual motor deficits are estimated to remain in about 8 to 30% of cases, the range in severity from mild clumsiness to ataxia and hemiparesis.[29]

Neurocognitive

Patients with demyelinating illnesses, such as MS, have shown cognitive deficits even when there is minimal physical disability.[68] Research suggests that similar effects are seen after ADEM, but that the deficits are less severe than those seen in MS. A study of six children with ADEM (mean age at presentation 7.7 years) were tested for a range of neurocognitive tests after an average of 3.5 years of recovery.[69] All six children performed in the normal range on most tests, including verbal IQ and performance IQ, but performed at least one standard deviation below age norms in at least one cognitive domain, such as complex attention (one child), short-term memory (one child) and internalizing behaviour/affect (two children). Group means for each cognitive domain were all within one standard deviation of age norms, demonstrating that, as a group, they were normal. These deficits were less severe than those seen in similar aged children with a diagnosis of MS.[70]

Another study compared nineteen children with a history of ADEM, of which 10 were five years of age or younger at the time (average age 3.8 years old, tested an average of 3.9 years later) and nine were older (mean age 7.7y at time of ADEM, tested an average of 2.2 years later) to nineteen matched controls.[71] Scores on IQ tests and educational achievement were lower for the young onset ADEM group (average IQ 90) compared to the late onset (average IQ 100) and control groups (average IQ 106), while the late onset ADEM children scored lower on verbal processing speed. Again, all groups means were within one standard deviation of the controls, meaning that while effects were statistically reliable, the children were as a whole, still within the normal range. There were also more behavioural problems in the early onset group, although there is some suggestion that this may be due, at least in part, to the stress of hospitalization at a young age.[72][73]

Research

The relationship between ADEM and anti-MOG associated encephalomyelitis is currently under research. A new entity called MOGDEM has been proposed.[74]

About animal models, the main animal model for MS, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) is also an animal model for ADEM.[75] Being an acute monophasic illness, EAE is far more similar to ADEM than MS.[76]

See also

- Optic neuritis

- Transverse myelitis

- Victoria Arlen

References

- ↑ "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis". Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases 14 (2): 90–95. April 2003. doi:10.1053/spid.2003.127225. PMID 12881796.

- ↑ "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis". Postgraduate Medical Journal 79 (927): 11–17. January 2003. doi:10.1136/pmj.79.927.11. PMID 12566545.

- ↑ "Childhood autoimmune neurologic diseases of the central nervous system". Neurologic Clinics 21 (4): 745–64. November 2003. doi:10.1016/S0733-8619(03)00007-0. PMID 14743647.

- ↑ "Post-vaccination encephalomyelitis: literature review and illustrative case". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 15 (12): 1315–22. December 2008. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2008.05.002. PMID 18976924.

- ↑ "Multiple sclerosis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and related conditions". Seminars in Pediatric Neurology 7 (2): 66–90. June 2000. doi:10.1053/pb.2000.6693. PMID 10914409.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis: two different diseases – a critical review". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 116 (4): 201–06. October 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00902.x. PMID 17824894.

- ↑ "Consensus definitions proposed for pediatric multiple sclerosis and related disorders". Neurology 68 (16 Suppl 2): S7–12. April 2007. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000259422.44235.a8. PMID 17438241. http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/documents/neurology/files/Consensus%20definitions%20proposed%20for%20pediatric%20multiple%20sclerosis%20and%20related%20disorders%20(International%20Pediatric%20MS%20Study%20Group,%20Neurology,%202007)(1).pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in 228 patients: A retrospective, multicenter US study". Neurology 86 (22): 2085–93. May 2016. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002723. PMID 27164698.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in childhood: epidemiologic, clinical and laboratory features". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 23 (8): 756–64. August 2004. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000133048.75452.dd. PMID 15295226.

- ↑ "Clinical and neuroradiologic features of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children". Neurology 56 (10): 1308–12. May 2001. doi:10.1212/WNL.56.10.1308. PMID 11376179.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children: outcome and prognosis". Neuropediatrics 34 (4): 194–99. August 2003. doi:10.1055/s-2003-42208. PMID 12973660.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a follow-up study of 40 adult patients". Neurology 56 (10): 1313–18. May 2001. doi:10.1212/WNL.56.10.1313. PMID 11376180.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Temporal Trends of Pediatric Hospitalizations with Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis in the United States: An Analysis from 2006 to 2014 using National Inpatient Sample". The Journal of Pediatrics 206: 26–32.e1. March 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.10.044. PMID 30528761.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: current controversies in diagnosis and outcome". Journal of Neurology 262 (9): 2013–24. September 2015. doi:10.1007/s00415-015-7694-7. PMID 25761377.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: an acute hit against the brain". Current Opinion in Neurology 20 (3): 247–54. June 2007. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3280f31b45. PMID 17495616.

- ↑ "Postinfectious encephalomyelitis". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports 3 (3): 256–64. May 2003. doi:10.1007/s11910-003-0086-x. PMID 12691631.

- ↑ "Multiple sclerosis and recurrent disseminated encephalomyelitis are different diseases". Archives of Neurology 65 (5): 674; author reply 674–75. May 2008. doi:10.1001/archneur.65.5.674-a. PMID 18474749.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis in children". Brain 123 (12): 2407–22. December 2000. doi:10.1093/brain/123.12.2407. PMID 11099444.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Fulminant demyelinating encephalomyelitis: Insights from antibody studies and neuropathology". Neurology 2 (6): e175. December 2015. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000175. PMID 26587556.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a long-term follow-up study of 84 pediatric patients". Neurology 59 (8): 1224–31. October 2002. doi:10.1212/WNL.59.8.1224. PMID 12391351.

- ↑ "Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis". Diagnostic Imaging. Case of the month 31 (12): 10. 2009. http://www.diagnosticimaging.com/case-studies/content/article/113619/1493546.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis in COVID 19- Systematic Review" (in en). Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology 25 (6): 11443–50. 2021-06-14. https://www.annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/7656.

- ↑ "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after SARS-CoV-2 infection". Neurology 7 (5): e797. September 2020. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000797. PMID 32482781.

- ↑ "The spectrum of MOG autoantibody-associated demyelinating diseases". Nature Reviews. Neurology 9 (8): 455–61. August 2013. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.118. PMID 23797245.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Anti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Central Nervous System Demyelination-A Novel Disease Entity?". JAMA Neurology 75 (8): 909–10. August 2018. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1055. PMID 29913011.

- ↑ "Post-dengue acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: A case report and meta-analysis". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 11 (6): e0005715. June 2017. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005715. PMID 28665957.

- ↑ "Measles-induced encephalitis". QJM 108 (3): 177–82. March 2015. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcu113. PMID 24865261.

- ↑ "Warning of serious brain disorders in people with mild coronavirus symptoms" (in en-GB). The Guardian. 2020-07-08. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/08/warning-of-serious-brain-disorders-in-people-with-mild-covid-symptoms.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 . International Pediatric MS Study Group"Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis". Neurology 68 (16 Suppl 2): S23–36. April 2007. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000259404.51352.7f. PMID 17438235.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Myelin basic protein as an encephalitogen in encephalomyelitis and polyneuritis following rabies vaccination". The New England Journal of Medicine 316 (7): 369–74. February 1987. doi:10.1056/NEJM198702123160703. PMID 2433582.

- ↑ "Immunologic studies of patients with chronic encephalitis induced by post-exposure Semple rabies vaccine". Neurology 38 (1): 42–44. January 1988. doi:10.1212/WNL.38.1.42. PMID 2447520.

- ↑ "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis". Neurology India 50 (3): 238–43. September 2002. PMID 12391446. http://www.neurologyindia.com/article.asp?issn=0028-3886;year=2002;volume=50;issue=3;spage=238;epage=43;aulast=Murthy.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Neurological complications of immunization". Annals of Neurology 12 (2): 119–28. August 1982. doi:10.1002/ana.410120202. PMID 6751212.

- ↑ "Adverse events after Japanese encephalitis vaccination: review of post-marketing surveillance data from Japan and the United States. The VAERS Working Group". Vaccine 18 (26): 2963–69. July 2000. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00111-0. PMID 10825597. https://zenodo.org/record/1259957.

- ↑ "Encephalitis after hepatitis B vaccination: recurrent disseminated encephalitis or MS?". Neurology 53 (2): 396–401. July 1999. doi:10.1212/WNL.53.2.396. PMID 10430433.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B vaccine related-myelitis?". European Journal of Neurology 8 (6): 711–15. November 2001. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00290.x. PMID 11784358.

- ↑ "Neurologic adverse events associated with smallpox vaccination in the United States, 2002–2004". JAMA 294 (21): 2744–50. December 2005. doi:10.1001/jama.294.21.2744. PMID 16333010.

- ↑ "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis associated with poliomyelitis vaccine". Pediatric Neurology 23 (2): 177–79. August 2000. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(00)00167-3. PMID 11020647.

- ↑ Adverse Events Associated with Childhood Vaccines: Evidence Bearing on Causality. The National Academies Press. 1994. pp. 125–26. doi:10.17226/2138. ISBN 978-0-309-07496-4. http://www.nap.edu/read/2138/chapter/7#124. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ "Para-infectious encephalomyelitis and related syndromes; a critical review of the neurological complications of certain specific fevers". The Quarterly Journal of Medicine 25 (100): 427–505. October 1956. PMID 13379602.

- ↑ "Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis in Children: An Updated Review Based on Current Diagnostic Criteria". Pediatric Neurology 100: 26–34. November 2019. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.06.017. PMID 31371120.

- ↑ "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis". Neurology 68 (16 Suppl 2): S23–36. April 2007. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000259404.51352.7f. PMID 17438235.

- ↑ "Comparative immunopathogenesis of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, neuromyelitis optica, and multiple sclerosis". Current Opinion in Neurology 20 (3): 343–50. June 2007. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3280be58d8. PMID 17495631.

- ↑ "Multiple sclerosis: one disease or many?". Frontiers in multiple sclerosis. London: Dunitz. 1999. pp. 37–46. ISBN 978-1-85317-506-0.

- ↑ "ADEM: distinct disease or part of the MS spectrum?". Neurology 56 (10): 1257–60. May 2001. doi:10.1212/WNL.56.10.1257. PMID 11376169.

- ↑ "Consensus definitions proposed for pediatric multiple sclerosis and related disorders". Neurology 68 (16 Suppl 2): S7–12. April 2007. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000259422.44235.a8. PMID 17438241.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis". Brain 133 (Pt 2): 317–19. February 2010. doi:10.1093/brain/awp342. PMID 20129937.

- ↑ "Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology 50 (1): 121–27. July 2001. doi:10.1002/ana.1032. PMID 11456302.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "Perivenous demyelination: association with clinically defined acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and comparison with pathologically confirmed multiple sclerosis". Brain 133 (Pt 2): 333–48. February 2010. doi:10.1093/brain/awp321. PMID 20129932.

- ↑ "Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis: Current Understanding and Controversies". Seminars in Neurology 28 (1): 84–94. February 2008. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1019130. PMID 18256989.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "Plaque-like demyelination in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) – an autopsy case report". Clinical Neuropathology 32 (6): 486–91. 2013. doi:10.5414/NP300634. PMID 23863345.

- ↑ "Comparative brain stem lesions on MRI of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, neuromyelitis optica, and multiple sclerosis". PLOS ONE 6 (8): e22766. 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022766. PMID 21853047. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...622766L.

- ↑ "OP65–3006: Clinical characteristics and neuroradiological findings in children with multiphasic demyelinating encephalomyelitis and MOG antibodies.". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. Abstracts of the 11th EPNS Congress 19 (supplement 1): S21. May 2015. doi:10.1016/S1090-3798(15)30066-0.

- ↑ "Children with multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and antibodies to the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG): Extending the spectrum of MOG antibody positive diseases". Multiple Sclerosis 22 (14): 1821–29. December 2016. doi:10.1177/1352458516631038. PMID 26869530.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "Infection-associated encephalopathies: their investigation, diagnosis, and treatment". Journal of Neurology 253 (7): 833–45. July 2006. doi:10.1007/s00415-006-0092-4. PMID 16715200.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 "A medical overview of encephalitis". Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 17 (4–5): 429–49. 2007. doi:10.1080/09602010601069430. PMID 17676529.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Acute haemorrhagic leukoencephalopathy: two case reports and review of the literature". The Journal of Infection 46 (2): 133–37. February 2003. doi:10.1053/jinf.2002.1096. PMID 12634076.

- ↑ "First case report of acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis following Plasmodium vivax infection". Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology 31 (1): 79–81. 2013. doi:10.4103/0255-0857.108736. PMID 23508437.

- ↑ "Acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis (Weston-Hurst syndrome) in a patient with relapse-remitting multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neuroinflammation 12 (1): 175. September 2015. doi:10.1186/s12974-015-0398-1. PMID 26376717.

- ↑ "Acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis of Weston Hurst secondary to herpes encephalitis presenting as status epilepticus: A case report and review of literature". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 67: 265–70. September 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2019.06.020. PMID 31239199.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 "Outcome of severe encephalomyelitis in children: effect of high-dose methylprednisolone and immunoglobulins". Journal of Child Neurology 17 (11): 810–14. November 2002. doi:10.1177/08830738020170111001. PMID 12585719.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 "Severe steroid-resistant post-infectious encephalomyelitis: general features and effects of IVIg". Journal of Neurology 254 (11): 1518–23. November 2007. doi:10.1007/s00415-007-0561-4. PMID 17965959.

- ↑ "Improvement of atypical acute disseminated encephalomyelitis with steroids and intravenous immunoglobulins". Pediatric Neurology 24 (2): 139–43. February 2001. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(00)00229-0. PMID 11275464.

- ↑ "Guidelines on the use of intravenous immune globulin for neurologic conditions". Transfusion Medicine Reviews 21 (2 Suppl 1): S57–107. April 2007. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2007.01.002. PMID 17397768.

- ↑ "Post-dengue acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: A case report and meta-analysis". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 11 (6): e0005715. June 2017. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005715. PMID 28665957.

- ↑ "Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a follow-up study in Taiwan". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 78 (2): 162–67. February 2007. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.084194. PMID 17028121.

- ↑ "Imaging of Acquired Demyelinating Syndrome With 18F-FDG PET/CT". Clinical Nuclear Medicine 43 (2): 103–05. February 2018. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000001916. PMID 29215409.

- ↑ "Executive function in multiple sclerosis. The role of frontal lobe pathology". Brain 120 (1): 15–26. January 1997. doi:10.1093/brain/120.1.15. PMID 9055794.

- ↑ "Neurocognitive outcome after acute disseminated encephalomyelitis". Pediatric Neurology 29 (2): 117–23. August 2003. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(03)00143-7. PMID 14580654.

- ↑ "The cognitive burden of multiple sclerosis in children". Neurology 64 (5): 891–94. March 2005. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000152896.35341.51. PMID 15753431.

- ↑ "Neuropsychological outcome after acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: impact of age at illness onset". Pediatric Neurology 31 (3): 191–97. September 2004. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.03.008. PMID 15351018.

- ↑ "Early hospital admissions and later disturbances of behaviour and learning". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 17 (4): 456–80. August 1975. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1975.tb03497.x. PMID 1158052.

- ↑ "Acute stress disorder symptomatology during hospitalization for pediatric injury". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39 (5): 569–75. May 2000. doi:10.1097/00004583-200005000-00010. PMID 10802974.

- ↑ "Neuromyelitis optica spectrum and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-related disseminated encephalomyelitis.". Clinical and Experimental Neuroimmunology 10 (1): 9–17. February 2019. doi:10.1111/cen3.12491.

- ↑ "Encephalomyelitis accompanied by myelin destruction experimentally produced in monkeys". The Journal of Experimental Medicine 61 (5): 689–702. April 1935. doi:10.1084/jem.61.5.689. PMID 19870385.

- ↑ "Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: a misleading model of multiple sclerosis". Annals of Neurology 58 (6): 939–45. December 2005. doi:10.1002/ana.20743. PMID 16315280.

External links

- Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases

- Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis Information Page at NINDS

- Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis Information

- Information for parents about Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|