Chemistry:Xylose

|

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

d-Xylose

| |||

| Other names

(+)-Xylose

Wood sugar | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| EC Number |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII |

| ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties[1][2] | |||

| C5H10O5 | |||

| Molar mass | 150.13 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | monoclinic needles or prisms, colourless | ||

| Density | 1.525 g/cm3 (20 °C) | ||

| Melting point | 144 to 145 °C (291 to 293 °F; 417 to 418 K) | ||

Chiral rotation ([α]D)

|

+22.5° (CHCl3) | ||

| -84.80·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Related compounds | |||

Related aldopentoses

|

Arabinose Ribose Lyxose | ||

Related compounds

|

Xylulose | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

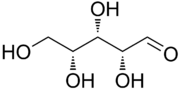

Xylose (cf. Ancient Greek:, xylon, "wood") is a sugar first isolated from wood, and named for it. Xylose is classified as a monosaccharide of the aldopentose type, which means that it contains five carbon atoms and includes an aldehyde functional group. It is derived from hemicellulose, one of the main constituents of biomass. Like most sugars, it can adopt several structures depending on conditions. With its free aldehyde group, it is a reducing sugar.

Structure

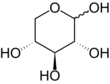

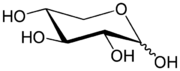

The acyclic form of xylose has chemical formula HOCH2(CH(OH))3CHO. The cyclic hemiacetal isomers are more prevalent in solution and are of two types: the pyranoses, which feature six-membered C5O rings, and the furanoses, which feature five-membered C4O rings (with a pendant CH2OH group). Each of these rings is subject to further isomerism, depending on the relative orientation of the anomeric hydroxy group.

The dextrorotary form, d-xylose, is the one that usually occurs endogenously in living things. A levorotary form, l-xylose, can be synthesized.

Occurrence

Xylose is the main building block for the hemicellulose xylan, which comprises about 30% of some plants (birch for example), far less in others (spruce and pine have about 9% xylan). Xylose is otherwise pervasive, being found in the embryos of most edible plants. It was first isolated from wood by Finnish scientist, Koch, in 1881,[3] but first became commercially viable, with a price close to sucrose, in 1930.[4]

Xylose is also the first saccharide added to the serine or threonine in the proteoglycan type O-glycosylation, and, so, it is the first saccharide in biosynthetic pathways of most anionic polysaccharides such as heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate.[5]

Xylose is also found in some species of Chrysolinina beetles, including Chrysolina coerulans, they have cardiac glycosides (including xylose) in their defensive glands.[6]

Applications

Chemicals

The acid-catalysed degradation of hemicellulose gives furfural,[7][8] a precursor to synthetic polymers and to tetrahydrofuran.[9]

Human consumption

Xylose is metabolised by humans, although it is not a major human nutrient and is largely excreted by the kidneys.[10] Humans can obtain xylose only from their diet. An oxidoreductase pathway is present in eukaryotic microorganisms. Humans have enzymes called protein xylosyltransferases (XYLT1, XYLT2) which transfer xylose from UDP to a serine in the core protein of proteoglycans.

Xylose contains 2.4 calories per gram[11] (lower than glucose or sucrose, approx. 4 calories per gram).

Animal medicine

In animal medicine, xylose is used to test for malabsorption by administration in water to the patient after fasting. If xylose is detected in blood and/or urine within the next few hours, it has been absorbed by the intestines.[12]

High xylose intake on the order of approximately 100 g/kg of animal body weight is relatively well tolerated in pigs, and in a similar manner to results from human studies, a portion of the xylose intake is passed out in urine undigested.[13]

Hydrogen production

In 2014 a low-temperature 50 °C (122 °F), atmospheric-pressure enzyme-driven process to convert xylose into hydrogen with nearly 100% of the theoretical yield was announced. The process employs 13 enzymes, including a novel polyphosphate xylulokinase (XK).[14][15]

Derivatives

Reduction of xylose by catalytic hydrogenation produces the sugar substitute xylitol.

See also

References

- ↑ An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (11th ed.), Merck, 1989, ISBN 091191028X, 9995.

- ↑ Weast, Robert C., ed (1981). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (62nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. C-574. ISBN 0-8493-0462-8..

- ↑ Hudson, C.S.; Cantor, S.M., eds (2014) [1950]. Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry. 5. Elsevier. pp. 278. ISBN 9780080562643. https://books.google.com/books?id=rUapoxXf-v4C.

- ↑ Miller, Mabel M.; Lewis, Howard B. (1932). "Pentose Metabolism: I. The Rate of Absorption of d-Xylose and the Formation of Glycogen in the Organism of the White Rat after Oral Administration of d-Xylose". Journal of Biological Chemistry 98 (1): 133–140. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)76145-0.

- ↑ Buskas, Therese; Ingale, Sampat; Boons, Geert-Jan (2006), "Glycopeptides as versatile tool for glycobiology", Glycobiology 16 (8): 113R–36R, doi:10.1093/glycob/cwj125, PMID 16675547

- ↑ Morgan, E. David (2004). "§ 7.3.1 Sterols in Insects". Biosynthesis in Insects. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 112. ISBN 9780854046911. https://books.google.com/books?id=AbXid2E-17YC&pg=PA112.

- ↑ Adams, Roger; Voorhees, V. (1921). "Furfural". Organic Syntheses 1: 49. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.001.0049. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=cv1p0280.; Collective Volume, 1, pp. 280

- ↑ Gómez Millán, Gerardo; Hellsten, Sanna; King, Alistair W.T.; Pokki, Juha-Pekka; Llorca, Jordi; Sixta, Herbert (25 April 2019). "A comparative study of water-immiscible organic solvents in the production of furfural from xylose and birch hydrolysate". Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 72: 354–363. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2018.12.037.

- ↑ Hoydonckx, H. E.; Van Rhijn, W. M.; Van Rhijn, W.; De Vos, D. E.; Jacobs, P. A. (2007). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_119.pub2.

- ↑ Johnson, S.A. (2007-08-24). Physiological and microbiological studies of nectar xylose metabolism in the Namaqua rock mouse, Aethomys namaquensis (A. Smith, 1834) (PhD). hdl:2263/27501.

- ↑ "Method of producing xylose" US patent US6239274B1, issued 1999-08-06

- ↑ "D-xylose absorption", MedlinePlus (U.S. National Library of Medicine), July 2008, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003606.htm, retrieved 2009-09-06

- ↑ "Nutritional implications of D-xylose in pigs". Br J Nutr 66 (1): 83–93. July 1991. doi:10.1079/bjn19910012. PMID 1931909.

- ↑ Martín Del Campo, J. S.; Rollin, J.; Myung, S.; Chun, Y.; Chandrayan, S.; Patiño, R.; Adams, M. W.; Zhang, Y. H. (2013-04-03). "Virginia Tech team develops process for high-yield production of hydrogen from xylose under mild conditions". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English (Green Car Congress) 52 (17): 4587–4590. doi:10.1002/anie.201300766. PMID 23512726. http://www.greencarcongress.com/2013/04/vt-20130403.html. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- ↑ Martín Del Campo, J. S.; Rollin, J.; Myung, S.; Chun, Y.; Chandrayan, S.; Patiño, R.; Adams, M. W.; Zhang, Y. -H. P. (2013). "High-Yield Production of Dihydrogen from Xylose by Using a Synthetic Enzyme Cascade in a Cell-Free System". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 52 (17): 4587–4590. doi:10.1002/anie.201300766. PMID 23512726.

|